Appendix

- Page ID

- 92500

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Contents

TERM REFERENCES 256

SUGGESTED PROJECTS 258

PANORAMA & HDR 270

ANIMATED GIFS 271

OTHER TECHNIQUES 272

PHOTOSHOP TECHNIQUES 274

COPYING FLAT MATERIAL 279

CELLPHONE CAMERAS 282

LIGHTROOM INSTRUCTIONS 285

CREDITS AND OTHER THINGS 314

*Page numbers noted are where the term is defined. Multiple pages signify increasingly complete definitions.

8 bit image 80

24 bit image 81

A

additive color 243

Adobe Photoshop format 132

Adobe RGB 244

albumin prints 228

ambient light 213

ambrotype 228

animated GIF 192

A or Av (Aperture or Aperture Value) 148

aperture 44, 142

auto-bracketing 124

auto-focus 62

automatic ISO 89

auto setting 23

B

background light 211

battery 43

bit depth 80

bracketing 124

built in flash 213

Bulb (B) 162

C

cabinet photograph 235

camera 38

camera color 248

camera flash 213

camera movement 165

camera obscura 223

camera shake 165

card photographs 235

cartes de visite 234

center-weighted metering 125

channel 81

CMYK 244

collodion 227

color gamut 245

color of light 207

color profile 247

Color Rating Index (CRI) 249

color space 243

color temperature 84

complex lens 60

compression 131

copy stand 213

D

Daguerreotype 225

depth of field 57, 146

Digital Negative (.DNG) 86

Digital Single Lens Reflex 38

Digital SLR (DSLR) 38

digital zoom 109

diopter adjustment 23

direction of light source 203

E

Edward Muybridge 233

effective size of light source 201

evaluative metering 125

EV corrections 123

exposure compensation 123

exposure meter 125

Exposure Value (EV), 123

F

fast lens 66, 152

field of view 101

fill light 211

film 236

fish-eye lens 66

flair 67

flash 191

fluorescent 84

focal length 101

focus 44

focus areas 63

format 25

f-stop 142

full-frame equivalent 108

full-frame sensor 40, 82

function menu 22

G

gaffer tape 216

gelatin 235

George Eastman 236

gray card 247

H

hair light 211

hard light 201

highlight clipping 121

Highlights 120

histogram 119

hot light 214

HUH 42

I

image stabilization (IS) 60

incandescent 84

infinity 65, 150

initializing 25

ISO 24, 185

ISO setting 44

ISO speed 87

J

Jacob Riis 234

JPEG 131

Julia Margret Cameron 231

K

Kelvin 84

Kodak 236

L

LED lights 215

lens hood 67

level 78, 119

Lewis Carroll 232

light color 249

light falloff 210

lock focus 62

long lens 101

lost highlights 120

M

Macro lenses 66

main light 211

manual focus 63

Matthew Brady 229

maximum aperture 150

megapixel 79

memory card 25

midtones 120

mirrorless camera 39

mixed light 207

M (Manual) mode 187

monolights 214

motion blur 164

N

natural light 213

neutral gray 122

noise 82, 87

normal focal length 101

number of light sources 206

O

O. G. Rejlander 232

one inch sensor 82

open up 144

overexposure 120

P

panning 168

panorama 192

partial metering 125

PASM dial 23

photography 223

pinhole camera 56

pinhole lens 54

pixel 78

plane of focus 143

portraits 210

P (Program) mode 23, 170

prime lens 109, 151

ProPhoto RGB 244

Q

quick menu 22

R

RAW format 23, 85, 129

RAW+JPEG 24, 130

reflections 203, 208

relative movement 166

resolution 131

RGB 79, 243

S

SD card 25

sensor 26, 38, 78

sensor size 82

sensor size and focal length 106

shadow clipping 121

shadows 120

short lens 102

shutter 162

shutter speed 44, 162

simple lens 59

soft box 215

soft light 202

S or TV (Shutter speed or Time Value) 169

spot metering 125

sRGB 243

stop 88, 123, 162

stop down 144

subject movement 166

subtractive color 244

T

telephoto 26, 101

telephoto zoom 104

texture 202

Timothy O’Sullivan 230

tint 85

tintype 228

tripod 42

U

umbrella 215

underexposure 120

unusual light 190

UV filter 41

V

variable focal length lens 102

variables of light 201

Vibration Reduction (VR) 60

W

wet-plate 227

white balance 83, 247

wide angle 25, 102

wide angle zoom 104

Z

zoom lens 102

zoom position 25

zoom range 103

SUGGESTED PROJECTS

The following projects are some that have been useful to students in my photography classes. These projects are very flexible, enabling the student to bring their own interpretations into the mix. They also highlight key aesthetic controls that are used by photographers. As mentioned in the introduction, it is important that you make prints of a carefully edited selection of your photographs.

Preliminaries

This is a simple one. Just go out and take photographs! Familiarize yourself with the work-flow: Try different things with your camera, then file your images on the computer. Edit for your best images and then make some changes to those images.

The Edge and the Light

The main tools that photographers use to interpret the world are edge and light. They are two basics differences of how camera vision departs from our vision.

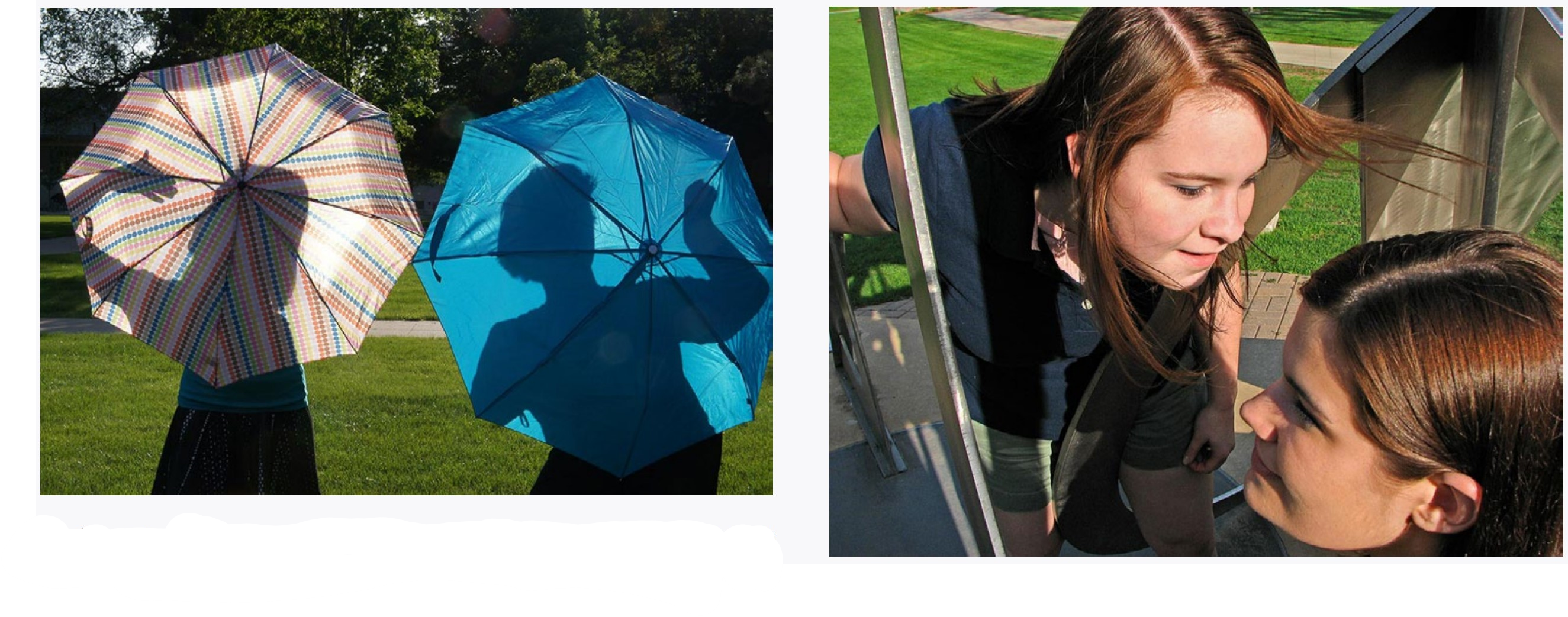

EDGE & LIGHTMolly Savage. The use of light is not obvious in this image, but the use of edge is very obvious. The image is not framed the way the viewer expects.

|

THE EDGE: Unless we are in a car or looking out some other window, we do not normally see the world with a frame around it. Photographs have definite edges (frames). This is one way they differ from reality or how they abstract reality. For this assignment do not just put your subject in the middle of the frame—use the edges very obviously. Cut things off, put them to the side. Hide them outside the frame. Make it edgy! At least unexpected. And if you don’t understand how to use edge, then just cut things off using one of the four edges of your camera frame. Put the thing people expect in the photograph half outside of it.

THE LIGHT: You are not photographing the things in the world, but light reflected off those things. Think about this while you are walking around with your camera. Do not photograph objects, photograph light. Look at light that is revealing things closely. If you don’t understand this, then take photographs of shadows. They obviously show light.

Each of your photographs should either show obvious light or obvious edge, and if possible, both!

Convert all of your images to black and white for this project. Color is great, but tends to obscure light interactions. If you can learn to see tonalities in black and white, it will make even your color images better.

And turn off your flash at this point and keep it off. Your built-in flash might be useful at times, but not when you are learning photography. All you really can learn is that you have to be close to your subject for the flash to illuminate it.

While doing this project you might find that nice light isn’t always very bright. In dimmer situations you need to brace your camera carefully and perhaps even use a tripod.

EDGE & LIGHT

TOP Suusen Ng. The edge is not obvious, although one could argue differently. The light is very obvious. BOTTOM Alex Gheysens. In this image both the light and the edge are used in obvious ways. Notice that these two images on this page ‘talk to each other’, with the guitar neck visually continuing to the top image.

|

Portrait

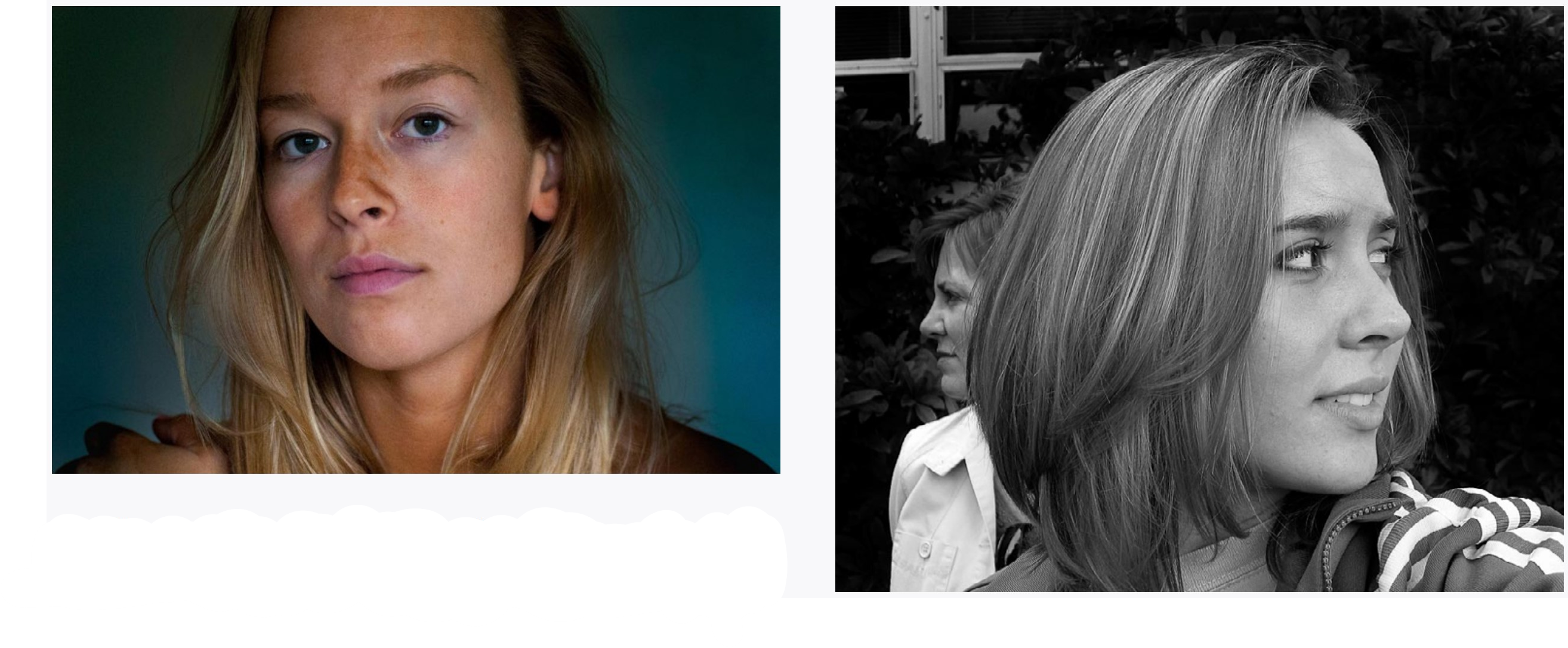

If you can imagine all of the photographs that have ever been taken in a big pile, how many of those would be pictures of people? I would venture a guess that it is a lot. People have a never-ending fascination with... people. Portraits get to the heart of this. Here a portrait is not a snapshot. It is a thoughtful rendition of someone else’s image. It says something about the subject, and most probably also some things about the photographer and perhaps even their relationship to the subject.

Obviously the formula portraits that you get from Walmart are not included in this definition. Nor are quick or candid snapshots. It is relationships that matter here. Who is the subject to you? What are they doing? How comfortable are they? Are they doing something? Try to make the images meaningful.

PORTRAIT

LEFT Leslie Davis. A portrait doesn’t have to be a head and shoulders shot. RIGHT Somto Mogbogu. This image is very formally composed. BELOW Katinka Kober. This interpretation is much more relaxed. Notice the lighting used for these images.

|

While taking these, experiment. Look at the light and how it falls onto a face. Notice the background and control it with the position of the subject and the camera. Perhaps point up or down at the subject (this makes a big difference). You might even try to direct them like a movie director directs the actors. Take control of the situation—remember that photographs are not reality, but an interpretation of it. Your interpretation.

Different subjects will present different challenges. You are shooting your subject, so understand their apprehension and nervousness. One fact that photographers are aware of is that people tend to lose their apprehension the longer you take to photograph them. So perhaps after the first half-hour of shooting they will drop that photo smile and present something more genuine.

Try to find a subject that is tolerant of you taking time with them, and make sure they are not hungry (feed them!) or otherwise preoccupied. If you know someone who loves to have their photograph taken, it is easier. Your subject may even help you make photograph decisions. This project is a collaboration after all.

PORTRAIT

LEFT Luke Gibbs. One could argue that this is not a portrait, but it could be argued back that the viewer is actually getting a lot of information about the person on the bench enjoying a spring day. RIGHT Haley Flores. This is a much more what we expect a portrait to look like, and could even be a senior picture. It doesn’t matter how you make a portrait, but it does matter if it is intentional. |

Color

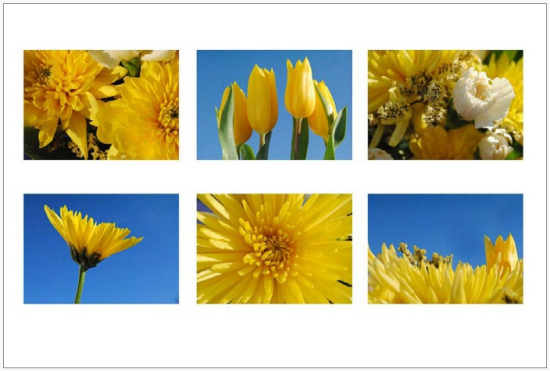

The importance of color in photography is self-evident. Most photographs taken today include color, and here you will try to be intentional about it. Intentional color is a tool that all photographers use.

Deal with color directly while doing this project—take images that depend on color. High or low saturation, dark or light colors, different colors. Look for color and arrange those colors in the viewfinder. What are the variations within a color or two colors? What colors are there in your frame and how do they compliment or contrast with each other? If there are neutral areas in the frame how do the colors react with those areas?

Think about colors you like. Are the colors subtle or do you like colors that pop?

Don’t just lay out a bunch of colored paper and shoot photographs of it (or the equivalent). Yawn. Instead go out and look for color and color combinations, look at your entire frame, arrange, &c.

COLOR

LEFT Kyle Barton. Red is a pretty loud color, especially in saturated amounts. ABOVE Miranda Fober. An old box of crayons. Notice how the photographer didn’t just lay some crayons out to photograph them. RIGHT Alicia Ford. Color doesn’t have to be bright to be effective. Neutral areas can help give colors harmony.

|

To help you be concerned about color, you want to set the camera to the white balance dictated by the light you are using—at the very least it helps you to think about the color of the light. And beware of two different colors of light hitting your scene. Light from a window will almost always have a different color than indoor light.

You will probably want to set your white balance back to automatic after you are done. If you are shooting in RAW format you can always override the camera’s white balance guesses, but if you are shooting in JPEG format a wrongly-set white balance will render the images with worthless color.

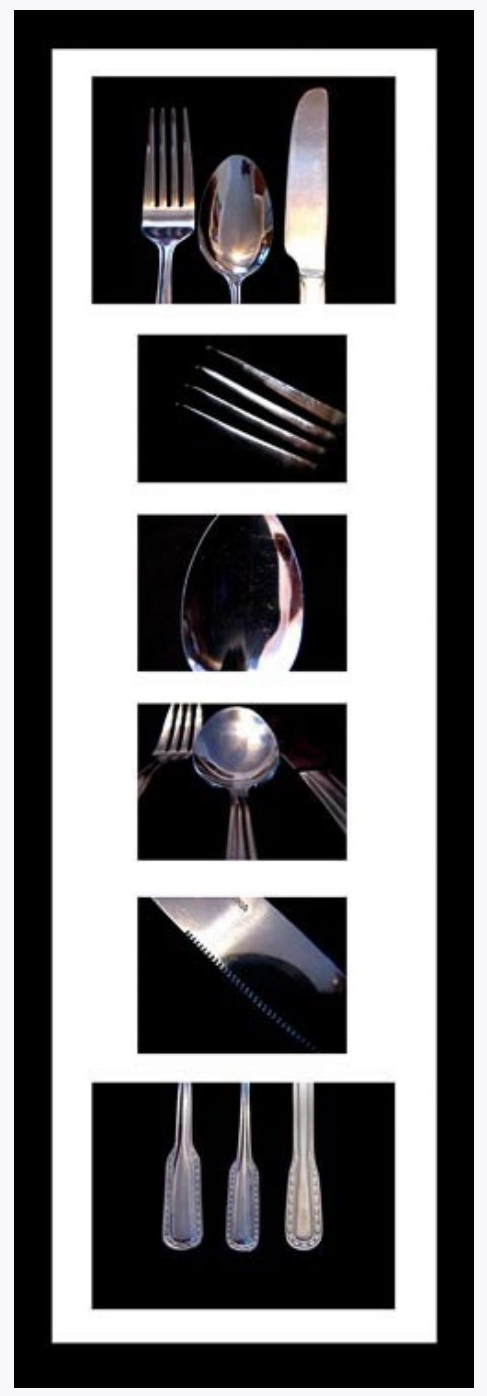

Interaction

When you see a person with a tree directly behind their head you probably don’t even notice. But if you take a photograph of this, you will, and the tree will seem to be coming out of their head. Visual interactions such as this are something that photographers notice and use with almost every photograph they take.

In simple terms, it is how photographs are composed. How are the near things interacting with the background? How do two things next to each other relate? By asking these questions you can avoid unintentional interactions and embrace intentional ones.

COLORStefan Hansen. If you walk around sensitive to color, you may be surprised at the combinations waiting to be photographed.

|

INTERACTIONMegan Karels. The interaction between the foreground and background is obvious.

|

Position two (or more) things in your frames to visually interact with each other in obvious ways. You can use something in the foreground and something in the background, but you could also have the things on the same plane.

INTERACTIONLEFT Jessica Glendenning RIGHT Matthew Ollendick In both of these photographs the interaction moves the viewer’s eyes back and forth between the two main subjects, which have similarities, but are not the same. In other words, the main subjects in each photograph are visually interacting!

|

Make sure you are making VISUAL interactions. Two people holding hands or someone drinking a soda are NOT necessarily visual interactions! The things in the camera frame need to relate visually. This can either be juxtaposition, where two things are placed near each other in the frame and contrast, or it can be two things that relate to each other and make your eye move back and forth between them (think of a picture of twins to understand this).

What you are really trying to do is get the different things in the camera frame to ‘talk to each’ other visually. If you are really at a loss on how to understand this, perhaps just fall back on a common photo-joke where someone in the foreground is ‘holding’ something in the background (like holding up a water tower or eating a car). Or you could have two people pretending to react to something very different expressions. Or you could select an object and put it in front of different backgrounds.

Self Portrait (not selfie)

This project departs from things photographers do every time they take a photograph, and instead presents you with a variety of technical and aesthetic problems somewhat like the ones photographers encounter daily.

In taking a self portrait there are three considerations: The first is how do you want to portray yourself for others to see? It can be fictional, real, one or more aspects. Remember, photographs are not reality, but an interpretation of it!

|

The second consideration is how you actually view yourself. At least some of these should include your face, which is kind of at the root of our self-perception (for better or worse). But there are also bits of you in people you love or objects you covet (or objects you love and people you covet!). Don’t use clichés here. Your teddy bear collection may be important to you, but does it really communicate that to others? ...Perhaps, but only if you do it right.

The third consideration is technical. How are you going to make the photographs? You could find reflective surfaces or use your camera’s self timer. Perhaps just your long arm, but stay away from making this a selfie, and be more thoughtful about it. Try not to have someone else take the photographs, since this introduces a variable that isn’t helpful.

Note: If you are doing this with the camera’s self-timer, focusing might be a problem. Just focus on something that is the same distance from the camera as you will be, then switch the focus to manual to lock in that distance.

SELF PORTRAIT

LEFT Kate Shindelar. This is very much like a standard portrait, but feels incredibly direct and honest. RIGHT Brei Aspenson. We find a lot of the identity of ourselves in our family, especially in our parents. This photograph could also fit very well with the interaction project. |

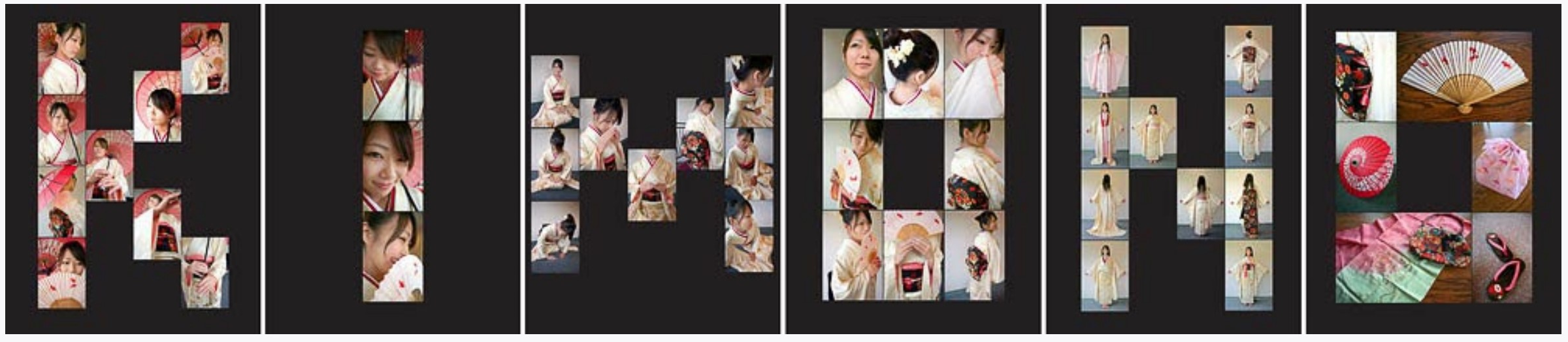

Multiple Images

You’ve probably noticed by now that photographs together can work very much like words and sentences together to express thoughts and observations. Photographic essays have had a long history from magazines to blogs.

Make a story using six or more images together. Display these together adjusting color and tonality so they work together. Through these photographs, and without words, you should explain something. How you do this is up to you. If a picture is worth a thousand words you have the equivalent of at least 6,000 words with this project.

MULTIPLE IMAGES

LEFT Jess Macauley. Six different views of flowers add up to a seventh interpretation. This approach is a photographic essay. ABOVE Shin Yasu. A narrative with a beginning and end to the story. RIGHT Megan Pratt. These images have strong visual relationships to each other. They also tell a (somewhat loose) story.

|

Your interpretation may be external—a very literal story like a photo-essay reading from the upper left photograph to the bottom right. Or it may be very internal, and explain your feelings or thoughts like a poem or philosophical abstraction. Or it may be anywhere in between. You may want these photographs to work together visually, but they don’t necessarily have to.

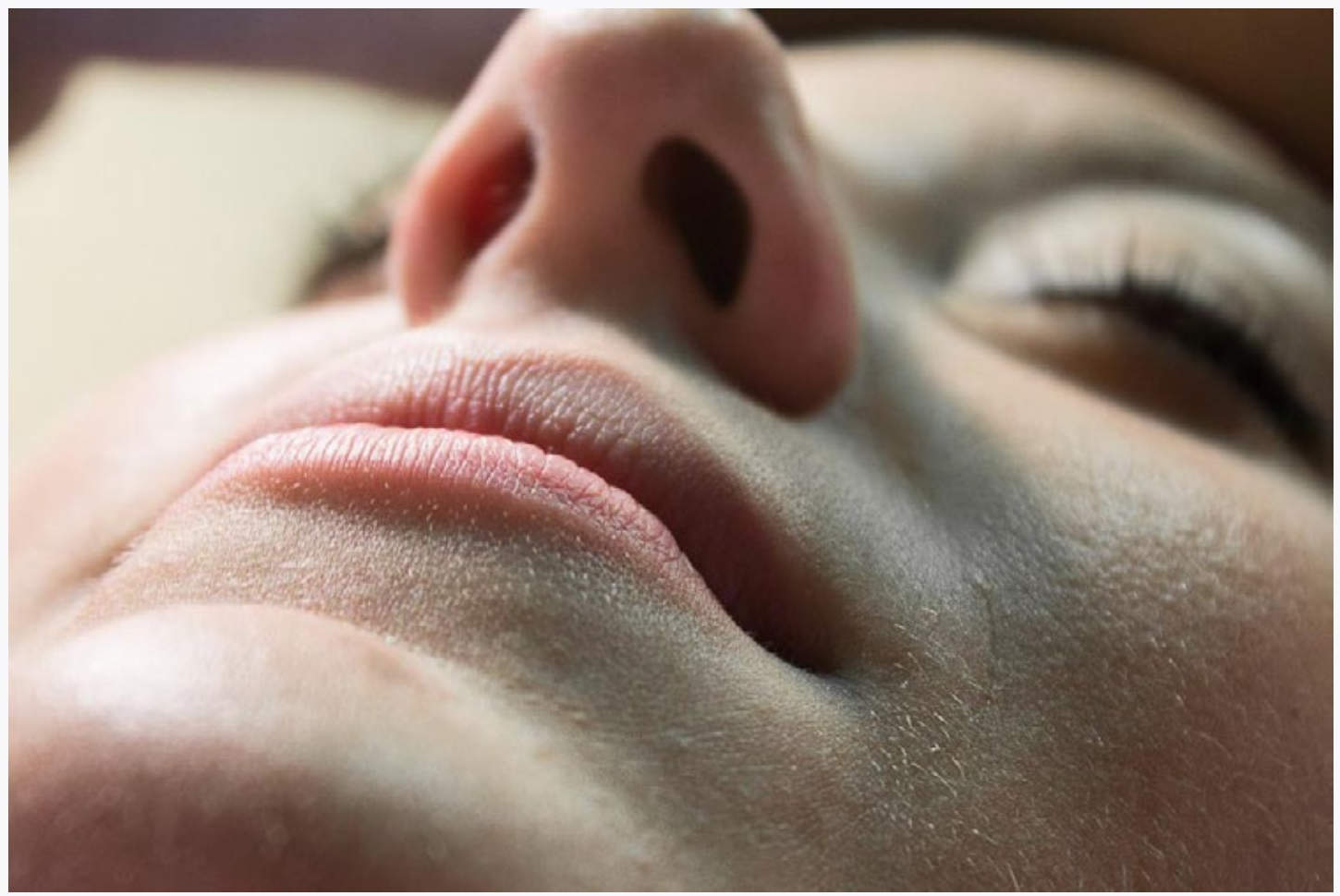

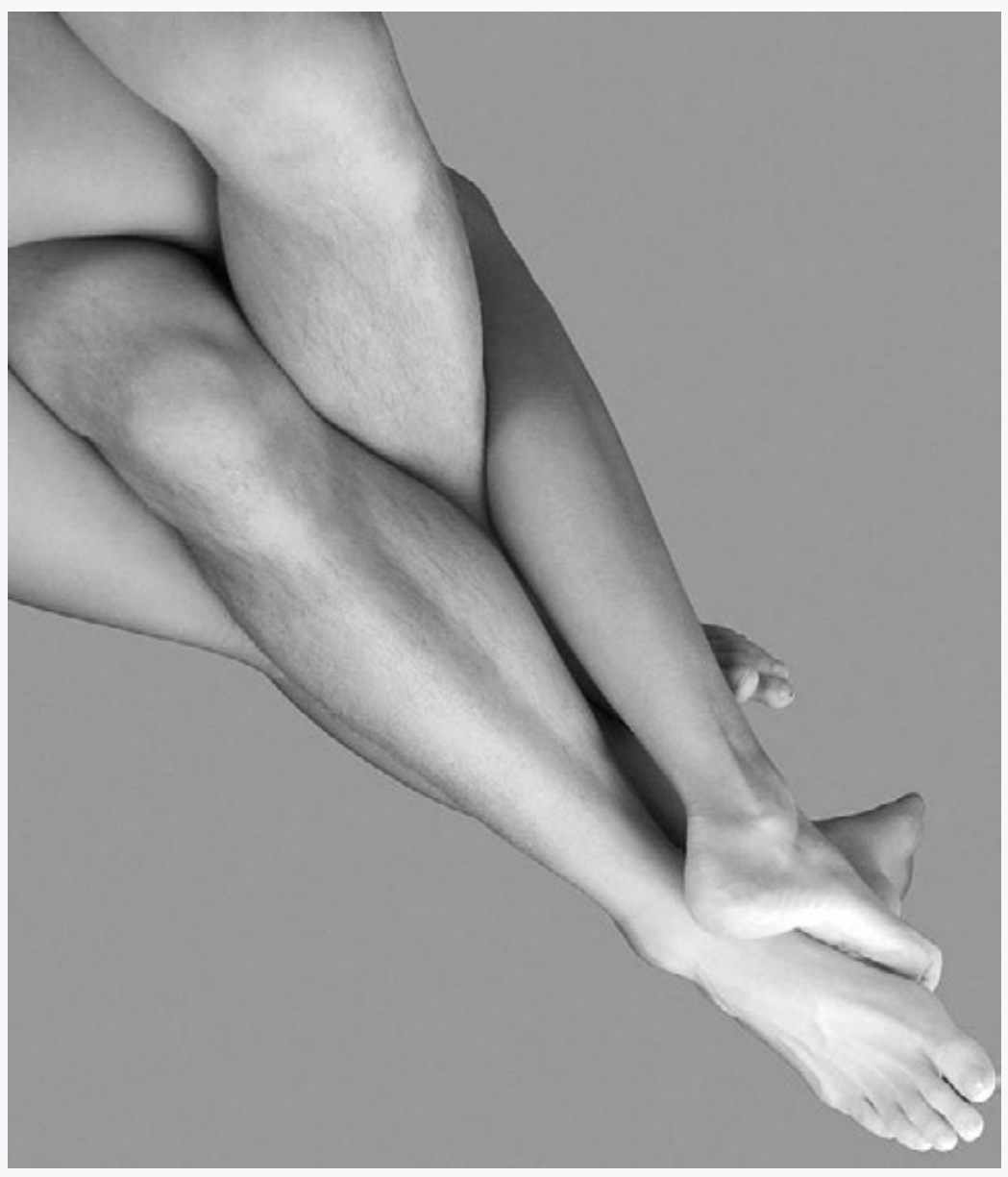

Body

Just about every person responds to the human body. In that pile of all photographs that have ever been taken, you won’t find too many photographs of the human body, but the ones that you do find will be appreciated. Photographs of the body can of course be sexual, but pornography is the ransom note of photographs: not thoughtful, but does get your attention. Do something thoughtful.

MULTIPLE IMAGESLEFT Roland Ferrie. Combining images can be done in Photoshop, a layout program, or just putting physical photographs together. RIGHT Chelsea Spangler. You don’t have to be very understandable when combining images. Poetry can be symbolic or more about a feeling than literal meaning.

|

Photograph different parts of the body. You can think of this as very much like the portrait assignment in the way that something like hands are expressed. Or you may think of it like the light and edge assignment and the way that the shape and texture are revealed by light. Or you may approach the assignment differently. Experiment.

In general, light is going to be extremely important to this assignment, and you may very well want to photograph using a window for light. What this means is that if you do not have a tripod or other support, your shutter speed will probably be very slow. Hold ‘er steady. And your aperture is going to be very wide. Focus carefully and don’t plan on having much depth of field. Try to anticipate how the final print is going to look before you shoot the photograph.

Color is also going to be very important in this project. You have several ways to make sure it is good. Shoot in RAW format (as always). Carefully adjust color balance (temperature), and saturation/lightness/hue. If you haven’t spread your photos out on your screen to directly compare color and exposure, then do it for this one. We can tell when skin color is ‘off’.

BODY

TOP Molly Schmidt. This is obviously not a portrait since the intent is to show the shapes of the body. LEFT Katie Zimmer. The contrast of the body with things that have different qualities can have interesting visual and literal interactions.

|

PANORAMA & HDR

PANORAMAS

To make panoramas in Camera RAW, simply select multiple images, then in the same menu go to Merge to Panorama.

The different projection options can be tried to see what works best. Basically, the choices come down to how the program deals with straight lines that no longer remain straight when the camera is turned (see illustration below).

Camera Raw needs plenty of overlap with the images (if in doubt take a lot of images), and it works best when all of the images are the same exposure.

You can also use this technique to either take a wider-angle view of something or stitch together images to make a high resolution file. In these situations shoot each image vertically for horizontal images (and vice-versa).

HIGH DYNAMIC RANGE

RAW images are capable of recording a wide range of brightnesses, but they can’t record very contrasty scenes like sunsets, night shots, or even looking out a window.

In very high contrast situations you can take several pictures at different exposures and combine them with the menu item Merge to HDR (in upper left illustration). The resulting HDR image has an incredible amount of tonal information which can be made visible with highlight/shadow adjustment and local controls.

There are limits to what you can do with HDR, and the resulting images can easily look very unnatural. Like bad postcards from the last century.

When taking photographs for HDR make sure you take enough photographs for Camera RAW to figure out how to align them. You only need the Deghost options if there is movement of something in the frame while you are taking the pictures.

ANIMATED GIFS

1 Take several photographs that you want to see move in sequence. It may be just two if you want simple movement, or many more if you want complex movements. Most GIFs use under 10 photographs.

2 Open these photographs in Photoshop. If they open in tabs, make your window very small and drag the tabs out of the window to make a separate window for each image.

3 With the move tool (top tool), drag the second image you took onto the window of the first image you took. Hold down the shift key while you are doing this to automatically align the images. Now take the third image (if there is one) and shift-drag it to the first image. Continue with all your images.

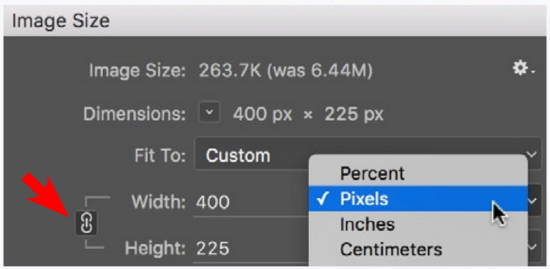

4 Go to the menu Image> Image Size. With constrain proportions (red arrow below) locked and resample image box checked (lines appear from it), enter a pixel dimension in either the width or the height boxes. GIFs are generally pretty small—anywhere from about 100 pixels wide to 800 pixels wide. Click Okay, then set the image to 100% (the actual size it will be in any other application) by double-clicking right on the magnifier tool. If it is too big or too small, undo your image size and do it again using a different pixel dimension value.

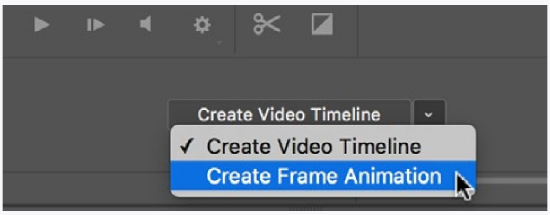

5 Open the Layers Panel by going to the menu Window> Layers. Now open the Timeline Panel (Window> Timeline). Choose Create Frame Animation as shown below (little triangle), then click on Create Frame Animation to activate it.

In the Layers Panel, uncheck the visibility (eye icon) of all your layers except the one on the bottom (titled Background). A thumbnail of this layer will show up in the Timeline Panel. Change the number under the thumbnail to the amount of time you want the image to show in your animation. Usually it is less than one second.

6 At the bottom of the Timeline Panel, click on the icon for a new frame (the ‘+’ icon next to the trash can icon). You will notice that this will make a second thumbnail image next to the first, but they are the same. Go to your Layers Panel, and click on the visibility of the layer called Layer 1. You will notice that now the second thumbnail in the Timeline Panel corresponds to your second image.

7 Repeat the above step for all the subsequent layers in your image. Test the animation by clicking the play button in the Timeline Panel, and adjust the times under the thumbnails to speed up all the frames or only some of them. Click and hold on the Once button in the timeline panel and change to Forever (if it is not already).

8 If you would like to add more frames (perhaps to make the animation run backwards after it runs forwards) just add more frames in the Timeline Panel, and with the specific frame selected, click only the visibility of the layer you want in the Layers Panel.

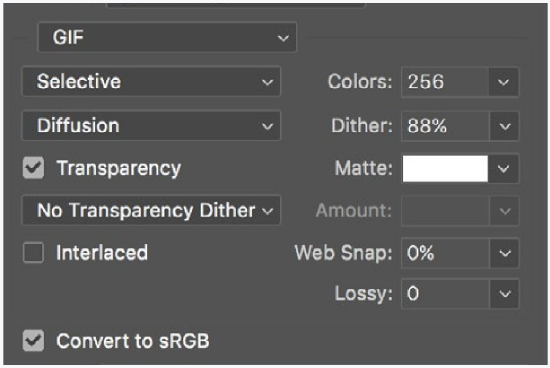

9 To save your GIF, go to File> Export> Save for Web (Legacy).

Fill in the boxes on the top right of the box as shown in the illustration below. Click Save, specifying where you want to save it. You may want to also save your Photoshop file in case you want to do further work on it.

That’s it! Test it by dragging the icon for your GIF to a web browser icon. Drag it into an email document and send it to someone. Or drag it into a presentation to show it there. Any application that supports animated GIFs will show it as you made it.

OTHER TECHNIQUES

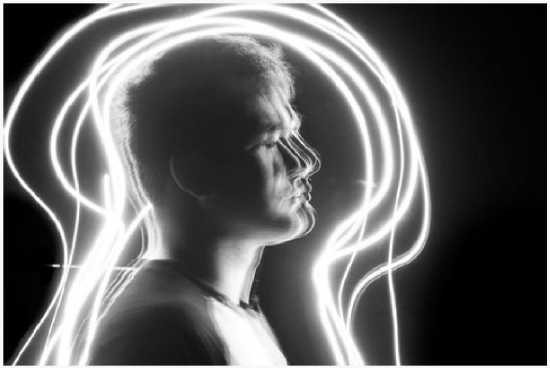

LIGHT PAINTING

There is no rule in photography that says that everything needs to be exposed at the same time. In a dark scene with your camera set to a long exposure you can do many things.

During a long exposure you can take a flashlight (or other light) and literally ‘paint in’ the lighting in a dark scene, moving the light across the area to expose certain parts of it.

Hold it on one part longer, it will be brighter.

You can also turn that light towards the camera, and make a drawing in the air, or do both things during one exposure.

Different lights have different qualities. LED lights sometimes flash on and off so quickly you don’t notice the flashing, but it they are moving, the camera will notice.

You can also do a lot with the color of lights, such as put colored pieces of plastic over them. With the light of a cellphone screen you can easily choose the color.

You are not limited to moving the lights. You can also move the camera to paint with light.

|

Ali Kilburg |

Austin MacTaggart |

Light painting steps:

1 Find a darkened room or go out at night.

2 Set your camera to manual mode.

3 Set your shutter speed to B or to a very long exposure like 30 seconds (if set to B you will have to have something to hold down the shutter button or a remote release).

4 Set your f-stop to whatever it needs to be (do some tests).

5 Set your focus to the approximate distance and turn off auto-focus.

6 Set your camera on a sturdy support, but for some you could move your camera during the exposure.

7 Take and retake as needed.

8 Experiment and have fun.

|

Tyler Jonsrud |

Gabrielle Celease Fox |

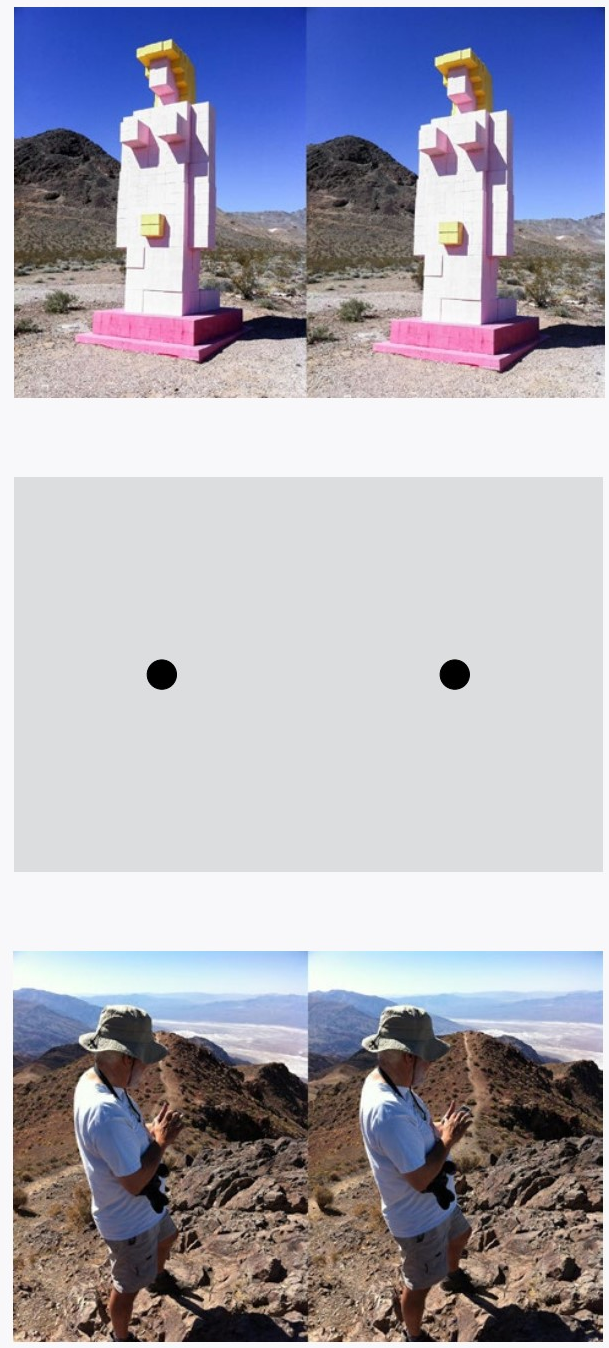

STEREO (3D)

Cross-Eyed Stereo

At normal viewing distance, look at the pair

of dots in the middle illustration and slightly cross your eyes until you see three dots, then concentrate on the middle dot and bring it into focus.

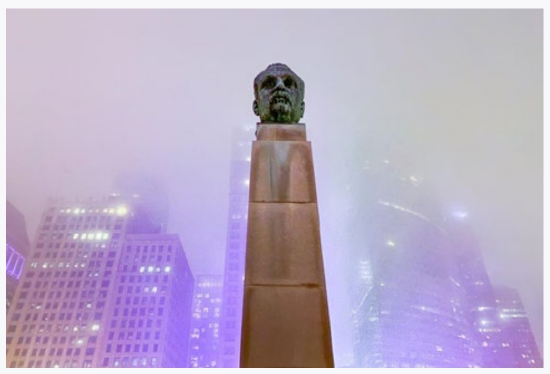

If you can do this, try it the same way with the top pair of images (the woman sculpture). You should see depth.

To make your own cross-eyed stereograph, simply take two photographs pointed at the same subject, but for the second image rock

a bit to the right so the images are taken from a point about two and a half inches apart. You can move more for an exaggerated depth. Don’t worry about being too precise.

On the screen (or in a print), put the image taken on the right to the left of the other and use this viewing technique. Keep them small since the bigger they are the more the viewer’s eyes need to be crossed.

Pie-Eyed Stereo

More difficult to view is the pie-eyed technique. Now again look at the dots, but this time stare past the dots. While continuing to stare, move your eyes closer to the dots until they overlap into three dots.

Here is the tricky part—concentrate on the middle dot, then slowly move away from the dots until you can see the middle one in focus, while still seeing the other two dots on the sides in your peripheral vision.

If you can do this, you will be able to do the same with the bottom pair of images, and you can see depth in the image.

Of course, you can also make or buy viewers that can make this viewing easier.

To make a pie-eyed stereograph, take photographs as you did for the cross-eyed, but this time put the right image on the right and the left on the left. As big as the pair can be is about 4 inches across since a bigger pair would require the viewer’s eyes to splay out in different direction—an ability very few people have!

PHOTOSHOP TECHNIQUES

This section refers to Photoshop as the image editing application, but there are others that work just as well with the following techniques.

Photoshop is an incredibly deep application. The reason for this is that multiple techniques can be combined. For example, image blur is one technique. But you can also limit blur to just colors or tones. Or, you can combine a heavy blur with no blur so that you have a unique quality of blur. Or you can just blur parts of the image or vary the blur across the image. What you can do with just a blur runs into hundreds or thousands of variations. And each will look different with different images.

There are three ways of approaching this issue of the ‘bottomless’ nature of Photoshop.

|

LEFT Heidi Hanson RIGHT Hanna Cox |

The first is to know everything you can about Photoshop. This would be another book in itself, and it still would be incomplete.

The second approach is to find things on the web that step you through a technique. This works best if you can find something that approximates what you are after.

The third way is a combination of the first two. Find instructions for techniques on the web, but try to understand what is happening and why the steps of the instruction are there. Look up the techniques for certain techniques you don’t understand. Buy a book on Photoshop.

That last method will help you learn the things YOU need to know about the application, and that is about all you can do. If someone tells you they know everything about Photoshop, they are a liar (a cheat, a dirty scoundrel—but I digress).

COMBINING IMAGES SIDE BY SIDE

There are many ways of combining multiple images in Photoshop. Often students’ biggest problem is actually figuring out exactly what they want to do before they start doing it.

A few pointers: Black or white is your friend. Transitions can be hidden with any color, but they are much easier with black or white.

Image sizing is actually very important, and you should figure it out. Otherwise it is easy to bloat file sizes into gigabytes by only combining a few images.

Consider using an application other than Photoshop for combining images. There can be much less of a learning curve because image sizing does not come into play as much. Illustration programs also allow you to combine type with your images without having to worry as much about typography’s additional resolution requirements.

If you are printing, consider wide format printing. Printers that take 24 inch to 44 inch paper are common, and you should be able to have a copy shop or photography studio make your image big. Prices vary widely.

|

TOP TO BOTTOM Ayako Shimizo Randi Westervelt Deidra Whipple |

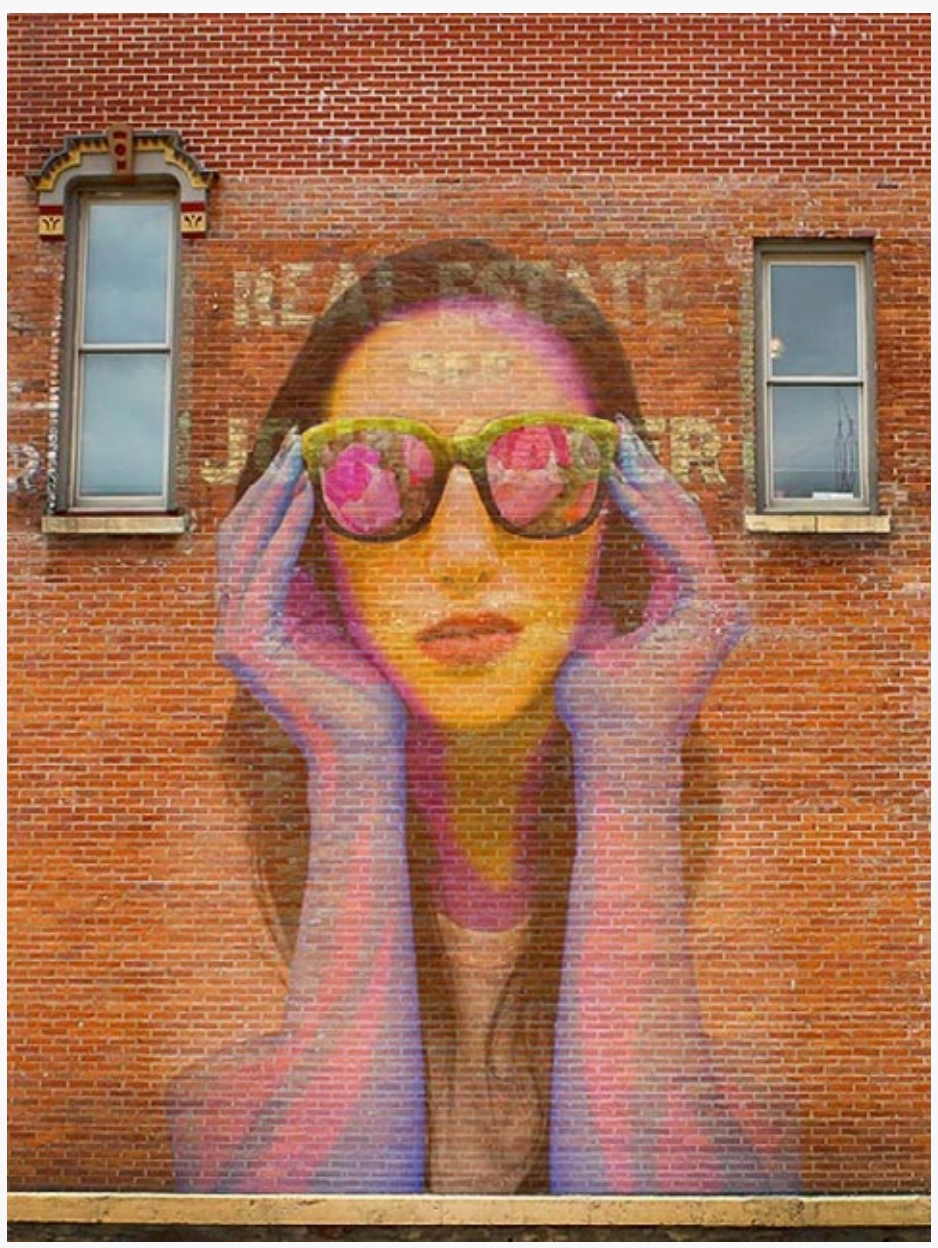

COMBINING IMAGES INTO ONE

Like combining images side by side, there are many ways of combining images together into one image.

Again, the first thing to do is get a firm concept of what you want to do, then figure out how to get there. But be prepared to change your concept somewhat to fit your skill level.

Often you need to tailor how you shoot the images as the first step in combining them. Do several tests of your idea before shooting the entire project.

Some ways of combining images are very easy. In the bottom right image the same person is photographed multiple times in a scene, then the images were simply combined as layers in Photoshop and parts were erased.

|

CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE Abby Shannon, Megan Howe, Luke Salzwedel, Trevor Finchcamp |

MULTIPLE IMAGE EFFECTS

Many special effects in Photoshop start with combinations of images. For instance, you can take a photograph of a textured surface, and then apply that texture to another image, either imparting it’s color, tonality, or both.

It is impossible to outline the infinite ways this can be done, but you can browse through Photoshop instructions on the web to get an idea of what is possible and how to do specific effects. For example, you can combine multiple images to get greater depth of field (focus stacking). Or ‘wrap’ images onto other images (image wrap or displacement map)

If you are going to be doing images with a lot of handwork, a pen tablet (often called a Wacom tablet because this brand is ubiquitous), is a critical piece of equipment. Some things work better with a mouse or track-pad, but drawing is not one of them.

|

LEFT TO RIGHT Matt Ollendick Michael Benson (fire self portrait) Courtney Mehus Lauren Kahler |

PHOTOSHOP MISCELLANY

There is a plethora of information on the web covering a myriad of Photoshop techniques to do this, that, or just about anything. As noted before, Photoshop is very deep since most effects used in combination produce still more effects.

Some common effects are polar coordinates, which makes an image a small planet; and selective blur, which is used for everything from making something look miniature to making a false lack of depth of field.

You can also colorize a black and white image or combine the original color of an image with a black and white version.

Just a tour through the Photoshop filter menu will present you with a multitude of ways to improve an image... or mess it up.

|

LEFT TO RIGHT Jessica Grant, polar coordinates Spencer Albers, selective blur Kendall Platt, filters etcetera Chrissy Schweiger, color and b&w |

COPYING FLAT MATERIAL

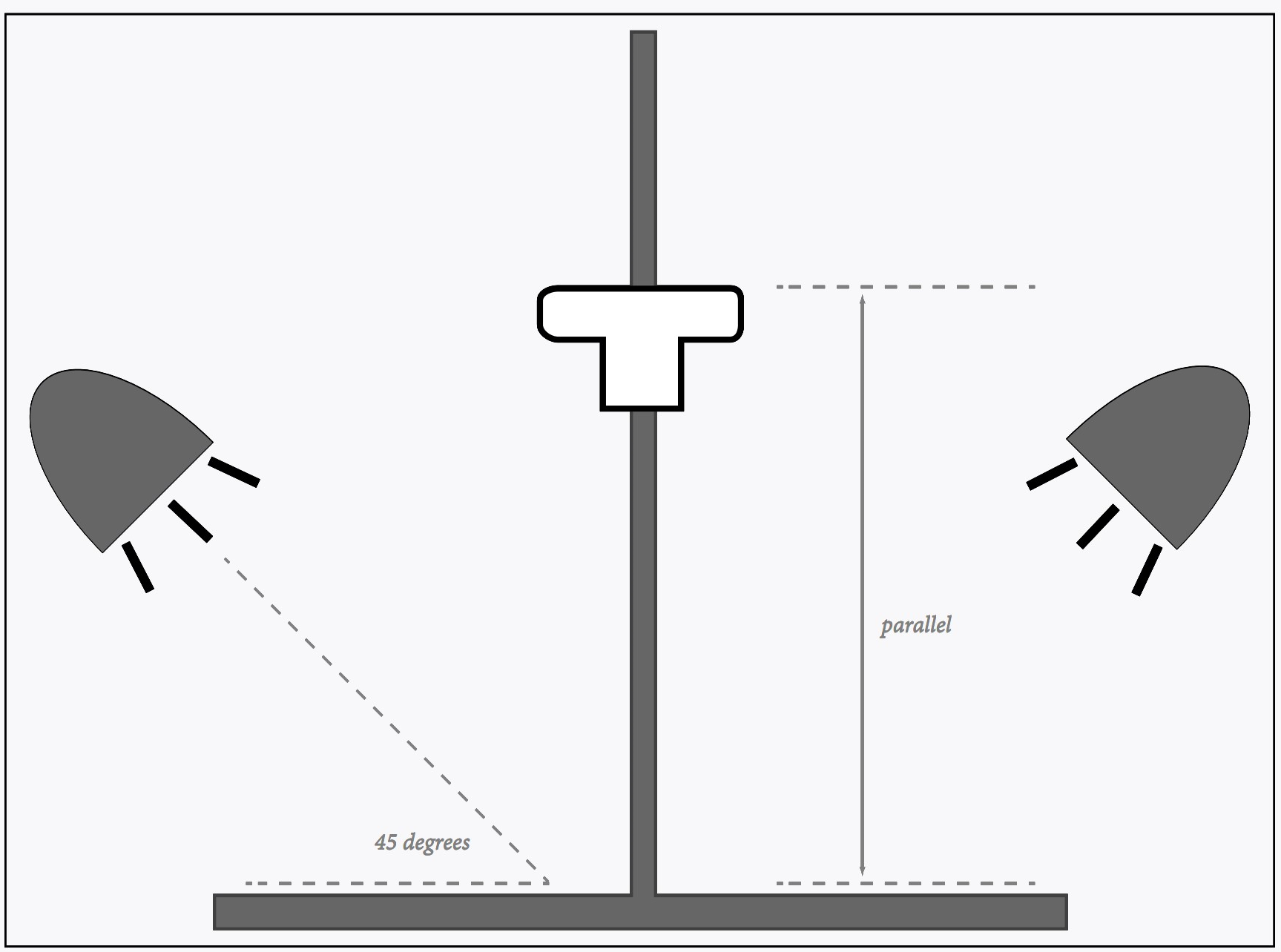

WITH A COPY STAND

Using a copy stand is the easiest way to take photographs of artwork (or anything that is flat and less than about 16 by 20 inches).

Preparation

Attach the camera to the copy stand, making sure back of camera is parallel to artwork. If it is not, rectangular material will be rendered trapezoidal. You can use a level to be precise.

If lights are not placed at 45 degrees to material, adjust them, making sure lights are pointed to the center of artwork or a little beyond center. Set your camera to a zoom setting about midway between wide angle and telephoto. All zoom lenses bend straight lines, but the effect is almost always less at this setting. For more accuracy you could do tests to see where the exact setting for your zoom lens renders lines straight.

Setting exposure

Turn off any lights other than your copy stand lights. If you have exposure controls on your camera, set it to manual mode and the lowest ISO. Adjust aperture to f-8 (on many lenses f-8 is the sharpest aperture). With artwork in place, set the shutter speed as necessary to obtain good exposure: If your material is a neutral gray, then it should be neutral gray in the resulting image, if it is light, then it should be light, and dark should be dark. For more accuracy, take a test photograph of a white sheet of paper. Adjust your shutter speed so that the histogram for the resulting photograph shows the hills near (but not at) the right side of the scale.

However you arrive at your shutter speed, use the same speed for all of your photographs. In this way, dark material will show up appropriately dark and light material appropriately light.

Setting the white balance

If you have your camera set to save JPEGs, you need to adjust the white balance. One way to do this is to set it for 3200k, or indoor lighting (represented with a light bulb symbol). For more accuracy, set it manually using a white sheet of paper (see your camera instructions). For even more accuracy, take a photograph of a white sheet of paper at first using RAW format. Take the rest of your photographs using RAW format and set all to the same color balance (color temperature) as your white sheet in your image editor like Photoshop. Always use RAW image format for the best quality.

Focusing

Ideally, every time you move the camera height you would want to focus manually. In practice, this doesn’t work very well. Instead, use the automatic focus on your camera. If your camera has a hard time focusing on material, temporarily place something with detail on it (like a sheet of typing). Press the shutter button down half-way to lock the focus, then remove the sheet and take the photograph.

Taking the pictures

Even if your shutter speed is fairly short, there is always the possibility of moving the camera slightly when pushing the button to take your photographs. To avoid this use the self-timer so that the camera fires after you push the button. Many cameras have a 2 second delay for the self-timer which is made for this purpose.

It is also a good idea to turn off any image stabilization (or vibration reduction) if your camera has these settings. If your camera is on a sturdy support having this setting on might actually increase blur.

For even sharper images you could use a remote release. Some cameras even have a way to lock the mirror up before you take the photograph so that the movement of the mirror won’t jar the camera, although this is generally not needed unless you have a very flimsy copy stand.

Take and look

Take several shots, then view them on the computer. Enlarge them to see if there are any problems. If there are straight lines (like the edges of the artwork) are they straight? Is the artwork framed okay? Is your exposure good? Are your colors fairly accurate or is there a color cast? Is everything sharp? When you are sure everything is okay, take the rest of the photographs.

|

Painting of Beirut Harbor by Arthur Frick |

WITHOUT A COPY STAND

Sometimes you can’t use a copy stand because there isn’t one available or your artwork is too large to be evenly lit with the copy stand lights. In this case, you can use a tripod, two lights, and a pin-up wall to make your own very big horizontal copy stand.

The illustration of the copy stand is seen from the front. Instead, imagine it as a lighting set-up looking from above with the artwork pinned to a wall.

Place the camera so that the back is parallel to the artwork. This is a little more difficult than with a copy stand. One easy way to do it accurately is to have someone hold a mirror flat on the center of your artwork. When you can see your camera centered in the mirror you can be sure everything is parallel.

How far away the lights (at 45 degrees to the artwork) should be is also something you will need to figure out. If they are too close, the work will not be evenly lit. If they are too far away, you will have to use overly long exposures and you run more risk of reflections, especially if the artwork has glass covering it. Turn on and off each light to better see how each is illuminating the artwork. Watch for any areas which are brighter with each light (hot spots).

How you arrive at your exposure, color balance, and other settings is just like with using a copy stand.

WITHOUT ANYTHING

Sometimes you might not have the luxury of having any equipment other than a camera (you definitely need the camera).

You want as much light as you can get while staying away from direct sunlight (which would accentuate any texture or defects in the thing you are copying). Also try to find a place that is amply lit from the side. The image above is photographing on a porch. You can also use a wall to put the artwork on or just put it on the ground and point the camera down.

Setting exposure

Just use the Program (P) setting on your camera. The light may change, so you don’t want it on manual mode. Also, the program setting does a pretty good job of determining the optimum shutter speed and aperture combination. For artwork that is lighter in tone, set your EV adjustment to +1 or +2. If the artwork is darker, set it to EV -1 or -2. Experiment.

Setting the white balance

Set the white balance on the camera to daylight. You could also use the same white balance methods as for the copy stand, but if the sun goes behind a cloud your white balance will change.

Focusing

If your camera has a hard time finding a focus, then point it at another part of the artwork, hold the shutter half way down to lock the focus, then recenter and take the photograph.

Taking the pictures

If you are shooting with a tripod, a level can make sure the camera is level with the art. If you are hand-holding your camera you definitely want image stabilization (vibration reduction) turned on. Also try to hold your camera against something. Your forehead works well if you are using a DSLR. If you are using a smaller camera with a viewing screen, put the neck strap around your neck and pull against it to steady the camera. If there is something else like a chair handy to steady the camera, use it!

If your pictures turn out blurry, then you may want to also set your ISO to a higher setting. Set it only as high as you need to get sharp images.

Other considerations

The success of this method really depends a lot on the reflective qualities of the artwork you copying. Thick acrylic or oil paintings have gloss surfaces that depart in small areas from being parallel to the main surface. Glass presents daunting reflection problems. Pencil lines may disappear if graphite is reflecting light badly. And so on.

But, if you are careful and thoughtful, you can do very high quality copies of many types of things with nothing but a camera and your keen eye focused on what you are doing.

PROCESSING THE IMAGES

No matter what method of shooting you use, processing the images in the computer should be fairly straightforward. Count on the lighter tones compressing—in other words, it is difficult to come up with something which has the exact same tonality as the original.

Most image processing programs have provisions for correcting non-parallel lines that result when your camera is not perfectly parallel to the copied material. These corrections can be automatically applied to all of your images at once.

Also, if you are using manual exposure, you should be able to correct exposure and contrast to one image and then paste the same correction to all the images.

CELLPHONE CAMERAS

Cellphone cameras are handy, traveling along with you almost everywhere you go, and are incredibly easy to use in most situations. They also have features that your camera might not have, such as automatic HDR, very good low-light capabilities, panorama capabilities, location data applied to every image... the list goes on, and yearly it expands to include more features.

The disadvantages of a cellphone camera mainly stem from a very small sensor — about the width of a pea. Physics dictates the limitations of image quality here, but various software ‘tricks’ (such as combining multiple images) help to mitigate those disadvantages. So much so, in fact, that for small images on a screen the images can look just as good as those taken with a camera. Actually, in the hands of someone without photographing experience, they can even look quite a bit better.

|

An unadjusted cellphone image. If you would have stood in the same place with the same cellphone you would have gotten the same image. Assuming your lens was wiped clean. |

|

A night shot without a tripod. With a camera this scene would have necessitated a tripod, but with a cellphone camera, it was just a pull from the pocket, an aim, and a push the button. |

Cellphone Camera Software

Even before you take a photograph with a cellphone, little AI gremlins get to work on that image. How much light is there? What does the contrast of lighting look like? What does the histogram look like? Is that sky or a face? The gremlins make a lot of decisions based on these and other things, all in the hopes that you will look at the image they made and congratulate yourself on a photograph well-taken. They can even give you different versions of the photograph starting before the time you pushed the button.

Those gremlins are smart in a way, and many times the fruits of their labor will give you the image you want. At other times they can present you with flesh-tones that look like a quarter-inch of makeup, skies that are so blue they only exist at forty thousand feet. And detail that looks like someone smudged it all up with a paintbrush. And the worst thing is you have little or no control to improve that image to suit it to your taste.

This sounds like a criticism, but it is really not. I use the standard camera app on my camera-phone at least half the time I use my cellphone camera, if not more. It is, after all, EASY. You don’t have worry too much about the amount of light available or holding the camera steady. You get a pretty good shot no matter how distracted you are, and really, if I wanted an image I could control a lot I would be using a dedicated camera.

But there are times when it would be nice to have some control over a cellphone image, and for that you need another application. Adobe Lightroom includes a camera function, and there are others that are quite inexpensive. At the time of this writing one of the best of these is Halide. With Halide installed on your phone, you can have better control while shooting since it is easier to selectively focus and change your exposure. But best of all, you have more control with your processing, since you can set it to shoot RAW images (in DNG format) in which the tones can be stretched and pulled when you edit the image. You can’t control tonality to the extent that you can with a dedicated camera image, but you are not stuck with the tonality the gremlins dictated when you took the image.

|

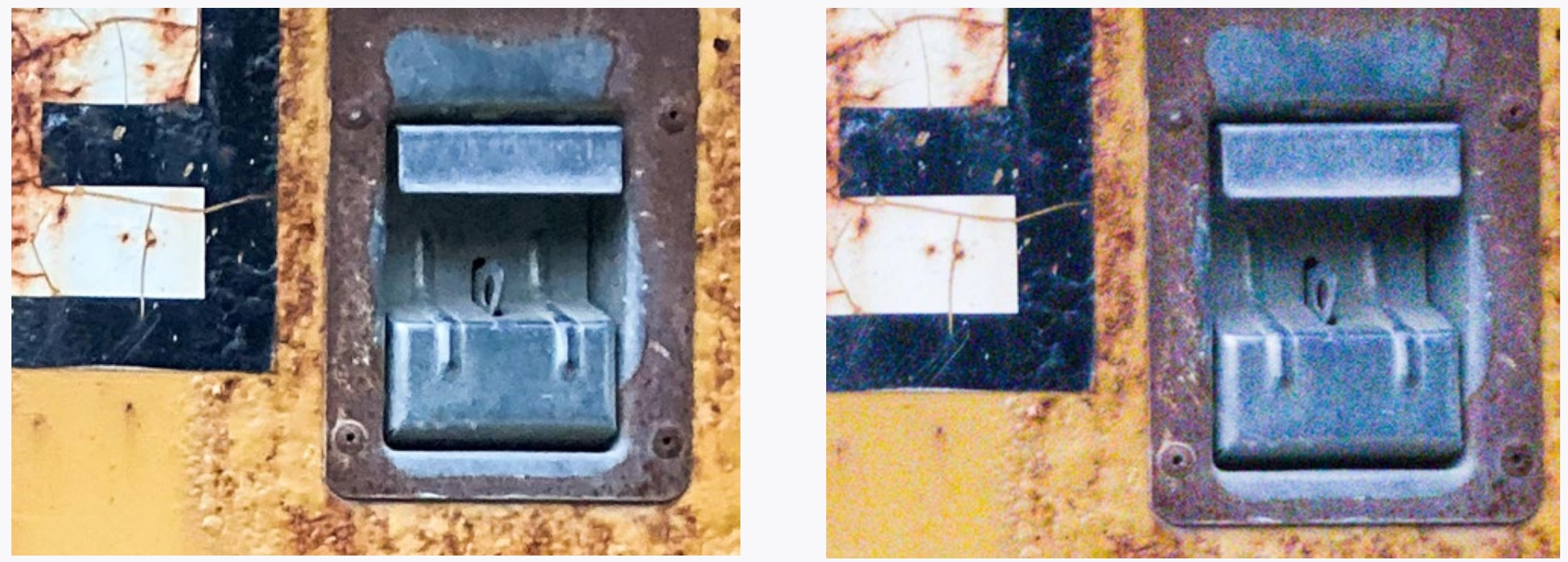

The photograph on the left is a small detail of an image taken using the Apple camera application. The image on the right was taken with an application which produced a RAW image (the exposure and contrast were adjusted). Regardless of which one you ‘like better’ the left image illustrates a bit about how the gremlins work on an image to mask imperfections by smoothing fine detail and enhancing edges. |

|

The painterly look of the camera’s software is clearly evident in this detail. |

Lens & Aperture

Because cellphone cameras must be thin, they cannot use an optical zoom lens. The digital zoom that is available just takes part of the image on the sensor, so the marginal quality of the image just gets worse. I am sure you have experienced this.

The best solution to this problem is to have multiple lenses on an cellphone camera. Actually this is multiple cameras, since each lens needs its own sensor. By combining these cameras, the software can mimic a zoom lens or do other tricks, such as forming a ‘depth map’ that can be used to different parts of the image blurry, (badly) simulating a large aperture.

This is useful since the aperture of cellphone cameras is not adjustable, and even if it was, would not be able to render depth of field: The actual focal length of the lens is simply too small to significantly put the background out of focus with photographs taken at normal distances.

Image Format

The applications that come with cellphone cameras give you photographs in either of two different formats. JPEG should be familiar to you, and it allows for small file sizes and compatibility with other software and devices.

HEIC format is also used. This format is much more flexible than JPEG, and allows multiple images to be stored in the same file package. So, multiple images or depth maps can be stored in the same place, allowing for later adjustments. Since this file is not compatible with many other applications, when you send an image or transfer it to another application it is often converted to another format and any additional images (or depth maps) are stripped from the HEIC file. For example, if you send someone a still image, that image will be sent as a JPEG. Or, if you send a small HEIC file animation made with an Apple cellphone, the file will be converted to a GIF file, an animation format that any device can decode.

RAW format does not need much explanation here. It is the same as other camera RAW formats, except you should not expect the wealth of information that RAW format can provide in cameras. You can still easily change the white balance, but exposure changes and color information will be more limited since the small sensor is not able to capture it in the first place.

The Future of Cellphones

The fact that cellphone cameras do as well as they do in ease of use and quality is a surprise to me. In other words, I don’t know what the future of cellphone cameras hold.

Physics limit the image quality at this point, but there are many experiments attempting to work around these limitations. For instance, one newer cellphone fits the length of a telephoto zoom lens into a thin phone by using a mirror to change the direction of the lens to align with the side of the phone. Another solution is adding a larger sensor to the wide angle lens, since that lens requires less distance from the lens to the sensor.

Perhaps more computing power will add to cellphone quality, or perhaps just more lenses. An array of lenses (with sensors) could theoretically enhance image quality, and other experiments, such as attaching a larger sensor/lens combination external to the phone might prove fruitful. Or might not.

Or, it might be that the technology that is already out there just gets more fine-tuned. Is there really a market for better quality cellphone images when at this point they are good enough for more people to post on Facebook and Instagram? Stay tuned.

1LR ADOBE LIGHTROOM

SET UP LIGHTROOM

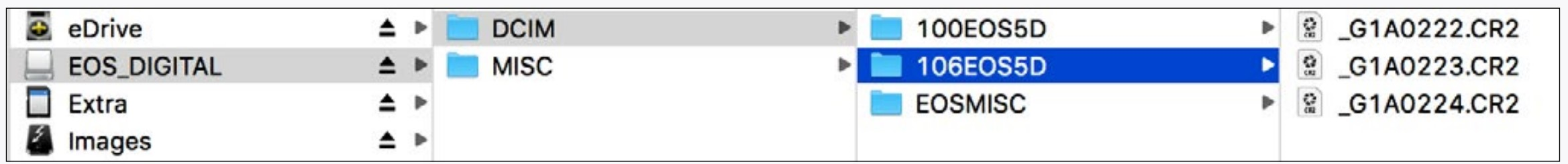

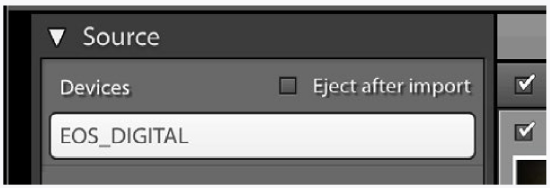

Before you even open Lightroom, connect the camera’s SD card to the computer. Also connect the hard drive or flash drive where you will keep your images and catalogue—you may want to make a folder on this drive called Images.

Now open Lightroom and go to File/New Catalog... in the menu at the top of the screen. Name your catalogue and save it your external drive (hard drive or flash drive).

As the application directs you, click the Import... button to show the Import window. On the upper left select your camera’s SD card as the source (where your images will be coming from).

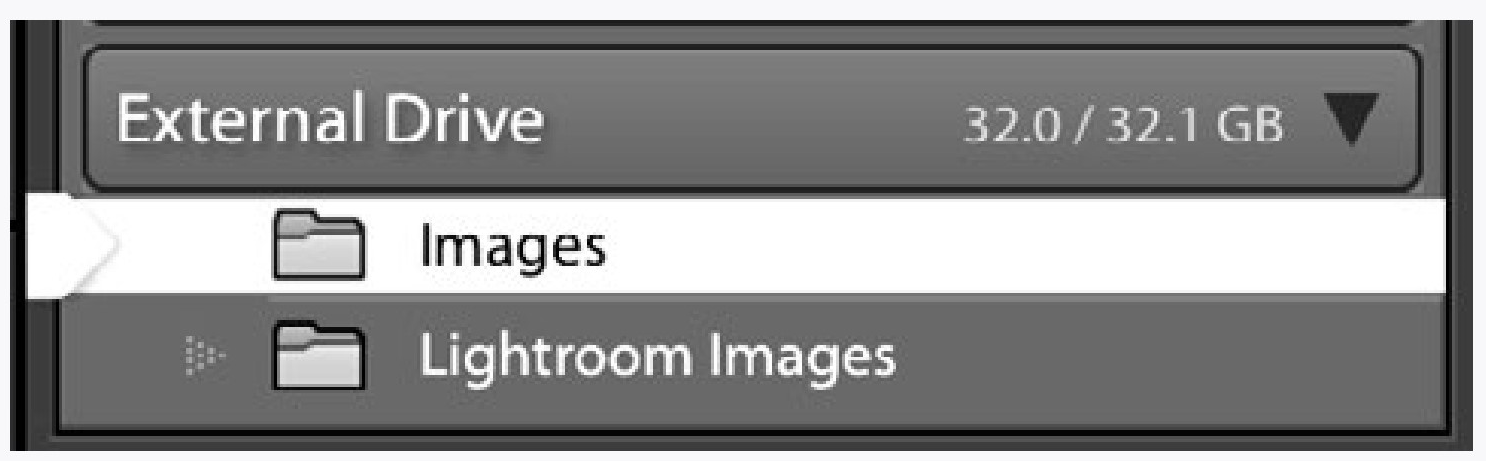

At the lower right of the Import window select your drive as the destination (where your images will be copied to).

In the illustration above I had previously made a folder called Images to put the photographs in. Do not put them in the folder that is titled with your catalogue name—this is a folder Lightroom made when you saved your catalogue (here named Lightroom Images).

Study the options you have when importing images. Most of these are on the right hand side of the Import window. Many of the options you might need now are self-explanatory.

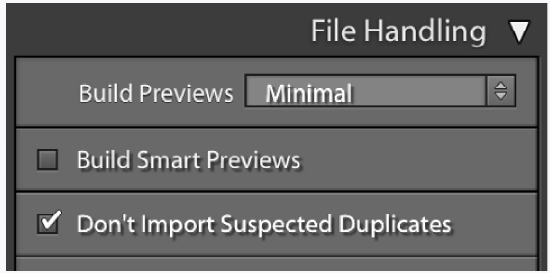

In the File Handling category (panel) there is an important option to not import duplicates.

You should choose this if it is not checked. Lightroom does not delete images from your camera’s SD card after you import them. Instead it assumes you will leave them on the card as a back-up, which is a very good idea. The next time you import images, it will overlook the images you have already imported with this option activated, only retrieving the newer images you have taken.

If you run out of room on your SD card, you can buy a new card or delete the images manually outside of the application (see below).

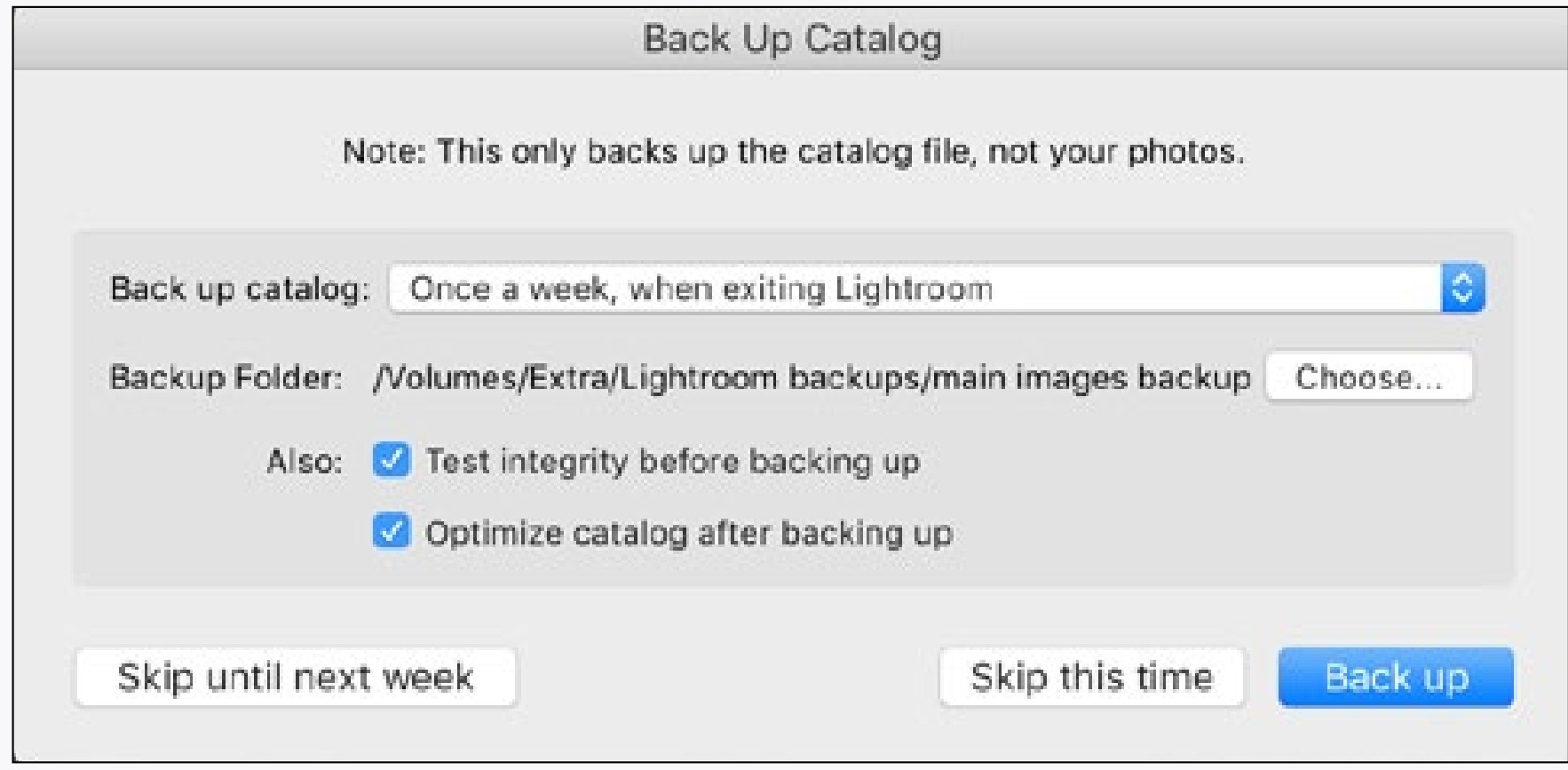

Speaking of backups, Lightroom will at some point ask you if you would like to back up your catalogue. Importantly, doing this will not back up your images, but only the information (such as organizing) you have added in Lightroom.

Since you are just starting out, you probably don’t need to back up the catalogue since you could easily rebuild it by making a new catalogue and re-importing the images.

One last thing to do is make sure your camera’s SD card has been ejected from the computer before you remove it. This can be done automatically from Lightroom (next to source option) or from outside the application. Not ejecting your card will hide forever any files you may have deleted (and subtract that file space from your card).

|

Your camera stores images in folders on the SD card. Folders and files can be deleted the same way as other files on the computer. |

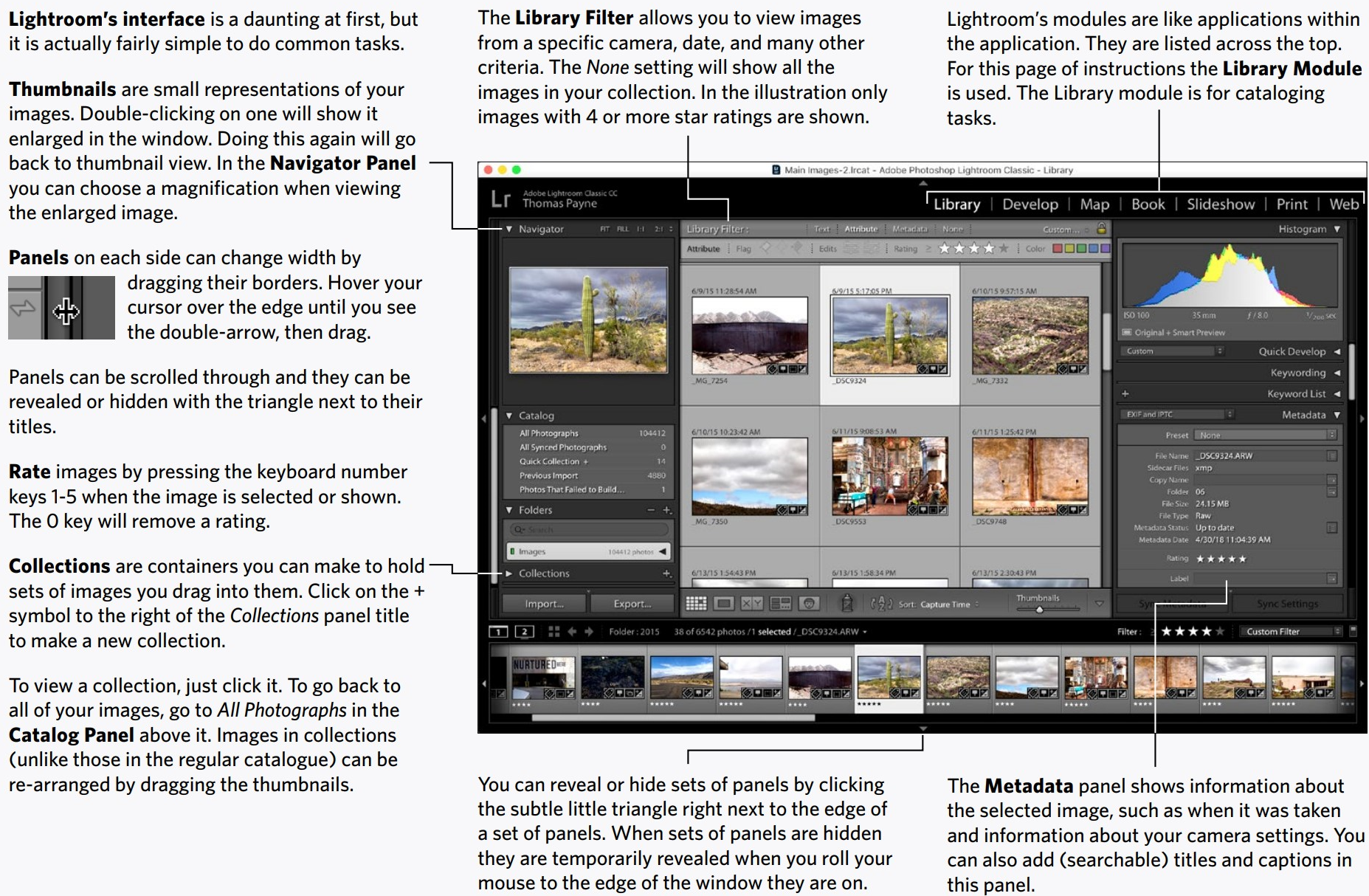

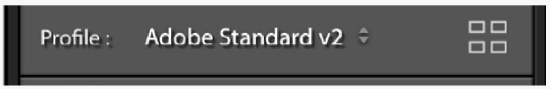

1LR LIGHTROOM DEVELOP MODULE

Adobe Lightroom doesn’t actually change your images, but instead adds instructions to your original images as to how they should be changed whenever they are viewed or exported. It does this by adding instructions to either the application, the image itself or more commonly in a separate file called a sidecar file.

What this means is that Lightroom doesn’t actually change an image until you export it—if you make wrong edits or completely mess up an image, you can always go back to the original, just as it came out of the camera.

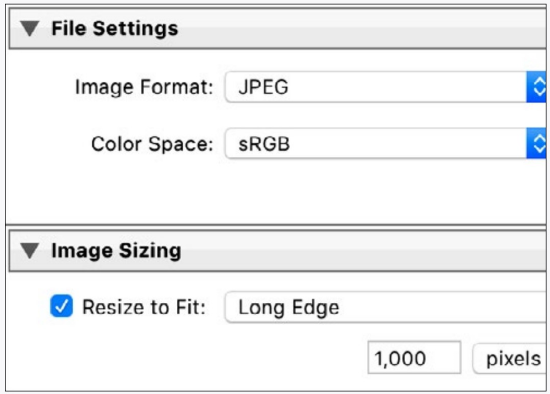

Since your adjusted RAW images cannot be opened in most applications, you might want to make a copy of the image to send to someone (or place into another program or whatever). In the Library module (see previous page) go to Export... (bottom left of the window) set the destination, give the file a name, and probably set the file format to JPEG with the color space set to sRGB. If you are emailing the image you can set the size as 1,000 pixels for the long edge.

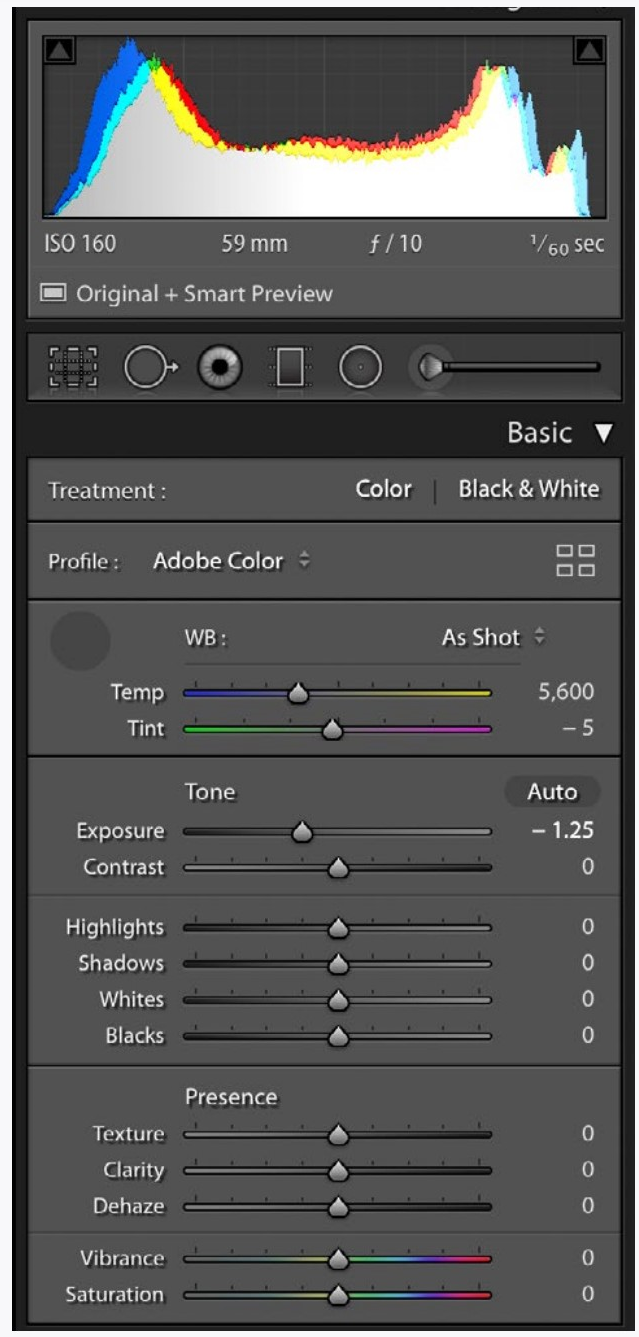

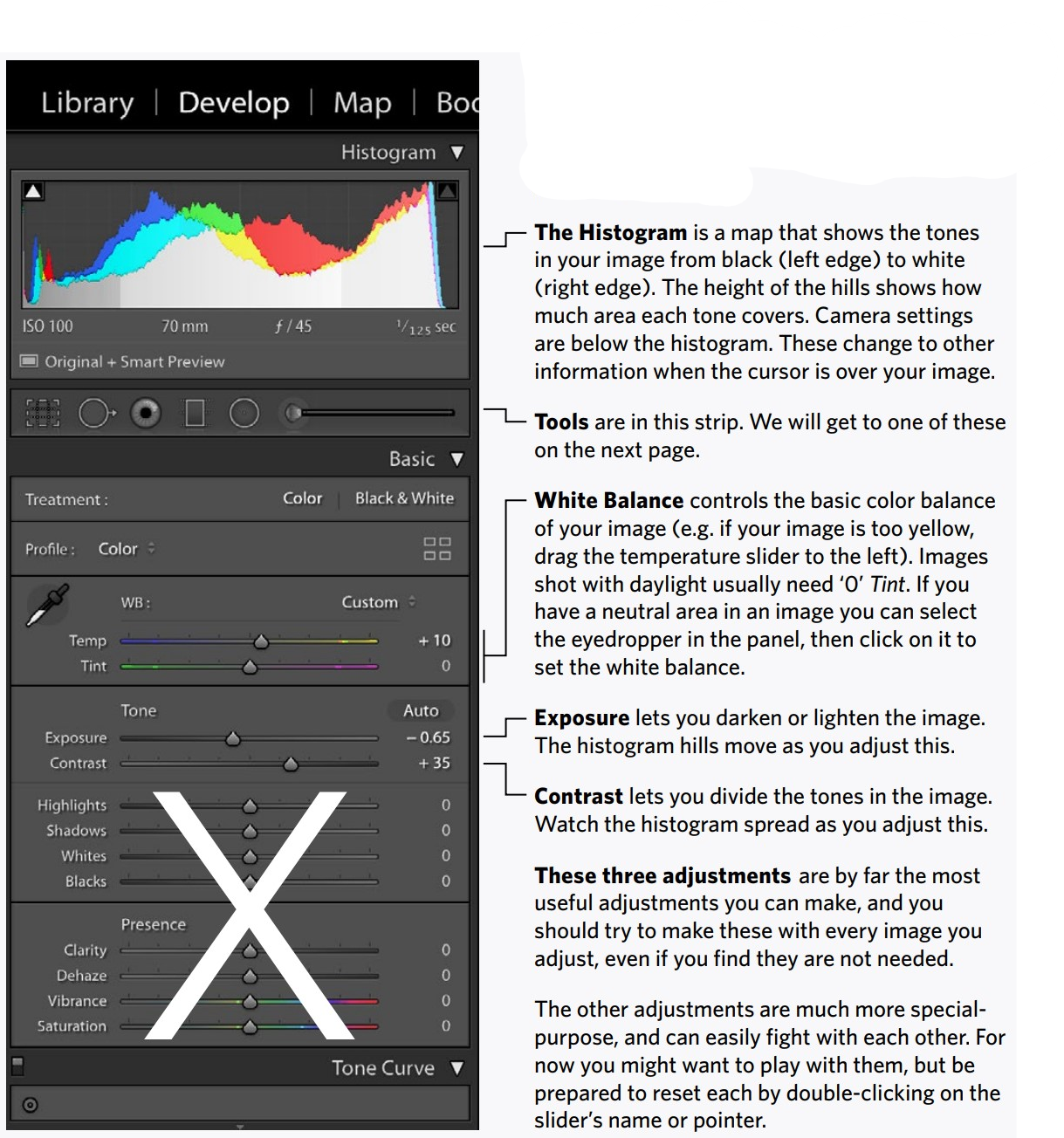

BASICS OF DEVELOP MODULE

Change Lightroom from the Library to the Develop module on the upper right. If you cannot see the Basic Panel as shown you can scroll the panels up and down.

These two views can be set to specific magnifications in the Navigator Panel. With an enlarged view you can also move the image around by dragging the box overlaying the Navigator panel’s image.

Below the image in the Develop module are the view controls. The first icon on the left will present the selected image (Loupe View). The second icon takes you to Reference View where you can select two different thumbnails to compare different images. The third icon allows you to compare the same image Before & After adjustments.

The small triangles next to the last two icons activate pull-down menus to choose the type of arranged views you want.

The three icons on the right allow you to switch adjusted and non-adjusted views. Essentially these allow you to undo adjustments or confirm adjustments in preparation for more adjustments.

Experiment with these buttons and get used to using them. Adjusting photographs is more than just sliding a bunch of sliders. Also, for explanations of the buttons, just rest your cursor over them for pop-up explanations.

You may have to scroll down in the left set of panels to see the History Panel. This panel allows you to select any previous adjusted state of the image, even long after you have made the adjustments.

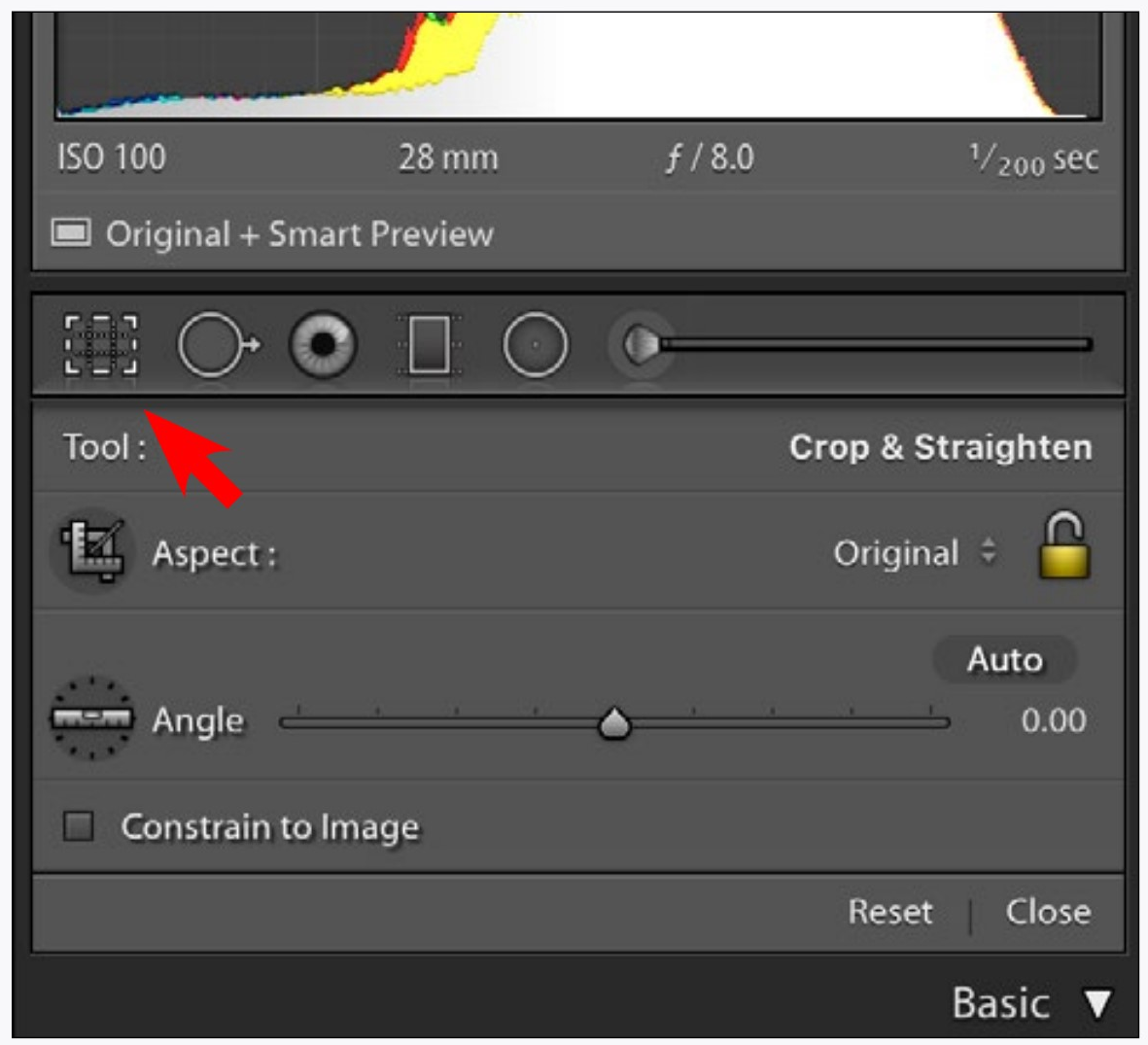

The Crop Tool (red arrow) is in the set of tools in the right set of panels. As with all of the tools, clicking on it will reveal options for the tool which appears below it. Clicking the tool again will confirm or cancel the tool and close the options panel.

Crop an image by dragging on the image itself. You can always reset the crop or constrain it to different proportions by using the options in the tool’s panel.

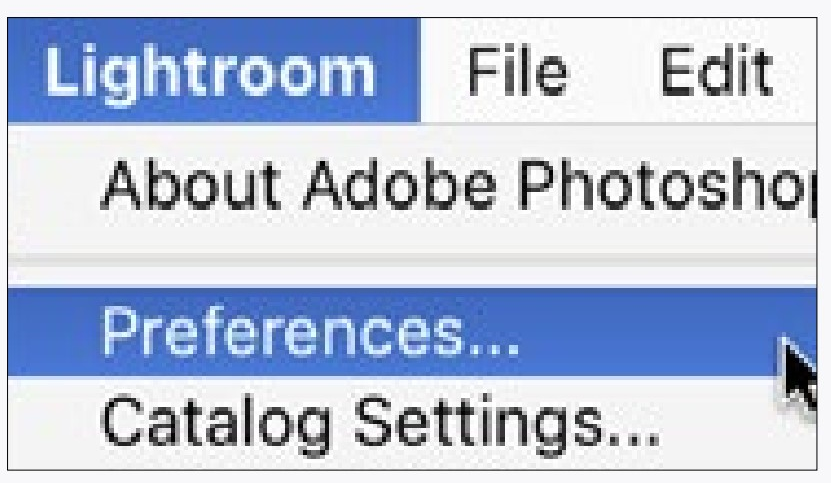

The preferences for Lightroom are in the Lightroom menu. Take a quick gander at these, but don’t change anything you don’t understand.

Each catalogue also has its own settings in the Catalog Settings directly below the preferences menu item.

1LR USING THE CONTROLS

You may notice that there are some controls that are not covered here, such as that little Auto button next to the exposure and contrast sliders. I bet you can figure many of these out yourself, and they may even be useful sometimes.

Keep the instructions on the previous pages at your side while you import, organize, and adjust your images in Lightroom.

Drag the sets of panels to resize them in Lightroom. Sometimes you might want the adjustments panels on the right to be small for a big image, other times you might want them big for easier adjustments. You also may want to hide the filmstrip at the bottom of the window by clicking that little triangle right near the edge of the screen. Try it.

Rate your best images, then view only those in the Library module using the controls at the top of the thumbnail views. Make a collection and put some of your images into it.

Adjust the white balance, exposure, and contrast with different images. Although not all images will need adjusting, you should get very familiar with what the changes look like.

Go ahead and try other image adjustments as well, but be aware that the other adjustments can easily work against each other and most images just need the first three adjustments.

COMPARE, DANG IT

It always amazes me how students will make changes to an image and then compare these changes to an image they only hold in their memories from before the changes were made. This only works for extreme adjustments, and is not good for eking out the best in an image.

Instead of comparing changes you have made to an image in your memory, use the before/after buttons. Sure, these are a little difficult to get the hang of, but they are important.

The following are questions you should ask yourself about this section of Lightroom instructions.

CAN YOU...

Import images using Lightroom and know where those images are being stored?

View and organize a set of images in Lightroom?Scroll through panels and resize sets of panels?Make a collection and put images into it?

Sort your best images by dragging them in a collection?

Find information about your images, including the time and date they were taken?

Export a sized JPEG image from Lightroom?Adjust the white balance of images?

Adjust the exposure and contrast of an image?Easily reset an adjustment slider to 0.

Zoom in or out of an image to see details or entire image?

Look at different areas of an enlarged image?

Set the white balance using the eyedropper when a neutral area is available?

Crop images?

Use comparison views to see changes clearly?

Use comparison views to move adjusted images back and forth or reset them?

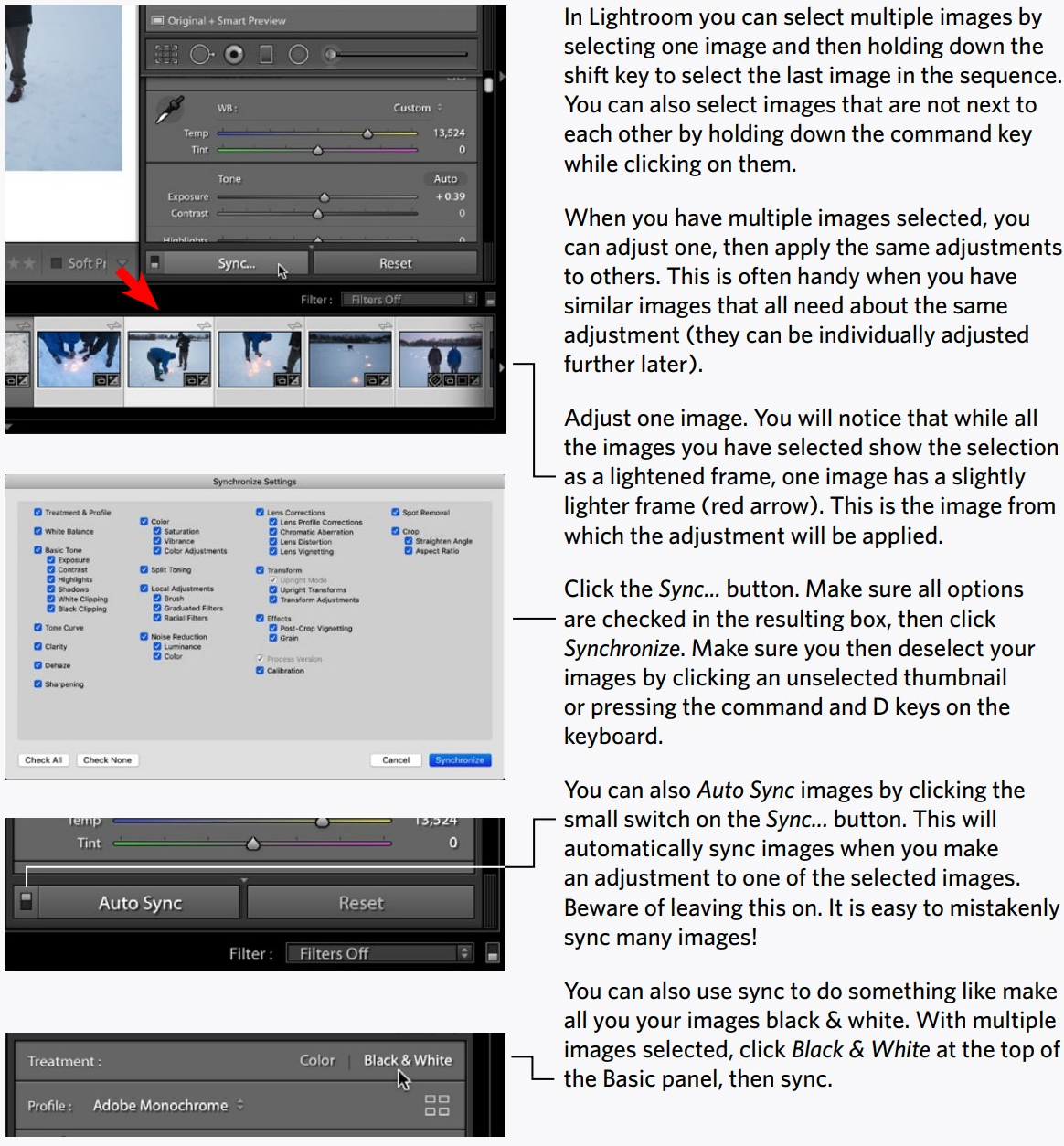

2LR MULTIPLE EDITS

Here are two things that don’t necessarily have much to do with the operation of Lightroom, but are necessary to control your images.

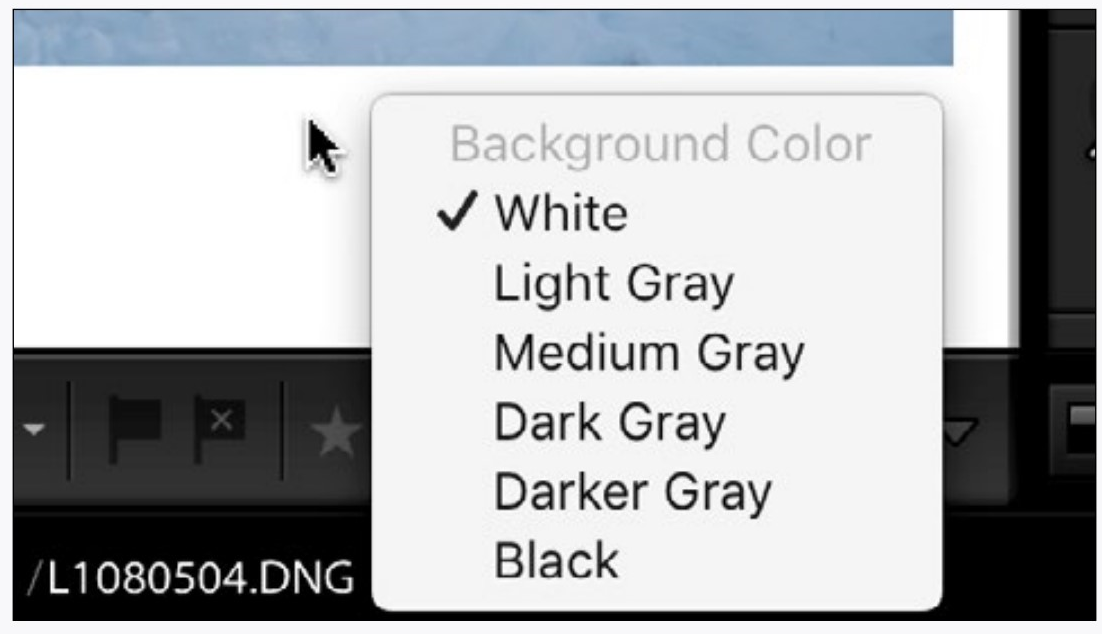

Set Lightroom Background to White

If you hold the control key and click and hold on the border of your image (you may need to reduce the magnification of your view to see the border), you will have the option to make the background white.

This is a good idea if you are going to print your image or otherwise show it on a white background in an email or on the web.

Adjust Your Display Brightness

Different computer displays have different brightnesses, and even the same display appears at different brightnesses relative to the level

of room light. This is a problem, since you can correct an image to be just perfect, but change the room light or the display and the result is not perfect.

The easiest method to adjust display brightness is to hold a piece of white paper to the side of the display and adjust the brightness of a white area on the display to match (or make a bit brighter) than the paper.

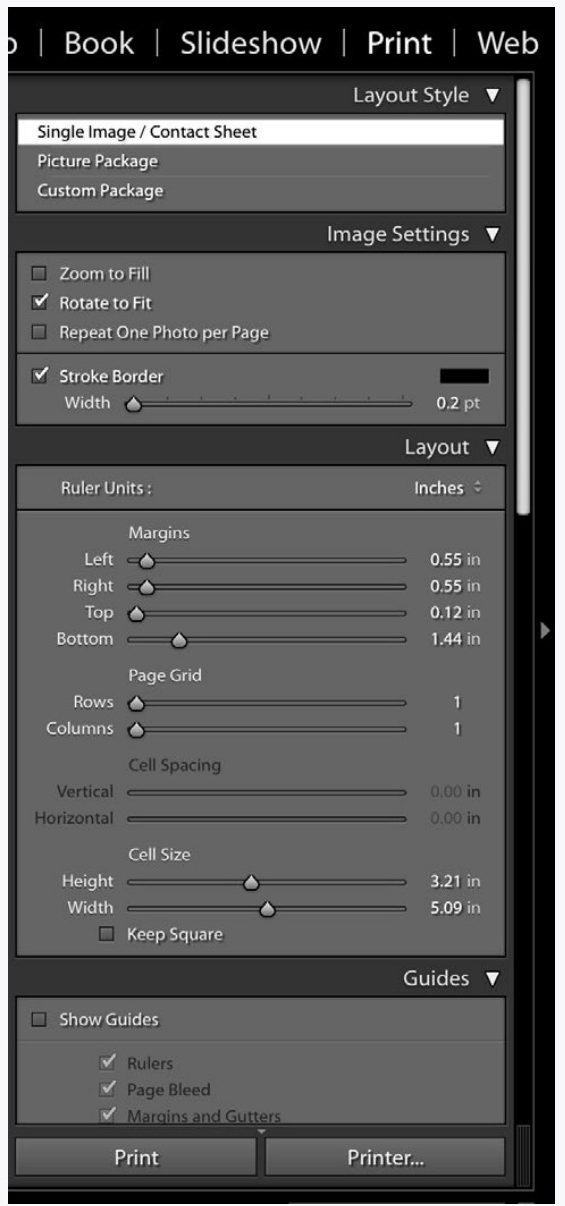

2LR PRINTING

To print from Lightroom, go to the Print Module at the top of the window. Most of the controls here are pretty self-explanatory (don’t forget to scroll to see all of them), and you get a preview of how your image will appear on the paper in the main window.

One thing that might seem odd is that there is no provision here for changing your paper size. This must be done by going File > Page SetUp... in the menus at the top of the screen.

As you change the Margin Options (borders of the print) in Lightroom you might notice that the numbers don’t quite correspond to your actual margins. One reason for this is that your image always remains in proportion. The other reason is that your printer may not be able to print as close to the margin as you have your numbers set to.

There are also options for printing multiple images on one sheet of paper. To do this, select multiple images and adjust the options in

the Layout panel until the preview shows the arrangement you would like.

The first time you print, choose the Printer... button at the bottom of the panels. Here is where you set up your printer. After you print using this button, for subsequent prints you can just click the Print button. The settings will remain as they were for the first print and the image will be sent to the printer.

Other Modules

Choosing modules in Lightroom is like changing applications, but as you have probably noticed, some things carry over from one module to the next, such as images that are selected and collections you are viewing.

You might not need these other modules, but if you are curious, here is what they do:

The Web Module is like printing, but instead of prints it generates web pages. The designs (templates) here are fairly long in the tooth, but who knows, you might find them useful.

The Book Module generates PDF books of images. Some book printers, such as Blurb, also make plug-ins that allow you to generate a book and send it to them for printing.

The Slideshow Module allows you to make slideshows for viewing with Lightroom.

The Map Module shows you where you took your images if they have GPS information embedded. Your camera phone probably embeds this information, but your dedicated camera probably does not.

You can also record location information on images by dragging their thumbnails onto the map. Selecting multiple images locates that set in one place.

Remember that all of these instructions are just to get you started, which in most ways is the hardest part. More information about specific parts of Lightroom are easily found elsewhere.

2LR USING THE CONTROLS

FIRST THINGS FIRST

Think about this for a second: Say you have a photograph that you are viewing on a dark Lightroom background. How are you going to know how light the lighter areas are? They may look very bright, but is that because your monitor is set to a high brightness? You can’t tell. I know that because I can’t either.

Set your background to white. Yes, I know it doesn’t look as cool, but for any photographs that are going to be printed or shown on a lighter background, it is the easiest way to judge the tones in an image.

But what about the darker tones? Yes, you can tell how dark the darker tones are better with the background set to black. But for a variety of reasons this is less of a problem unless the final viewing situation is on a black background.

Adjust your display brightness or you may have an embarrassingly bad image when you show someone the photograph you adjusted on a display that was set too bright.

MULTIPLE IMAGE ADJUSTMENTS

Try selecting a few images in Lightroom, then go through the steps of adjusting one then applying that adjustment to others.

REVIEW

Now is a good time to go back to the previous chapter (1lr) and review the things there while you are sitting at the computer. These are important basic techniques that we will be building on later.

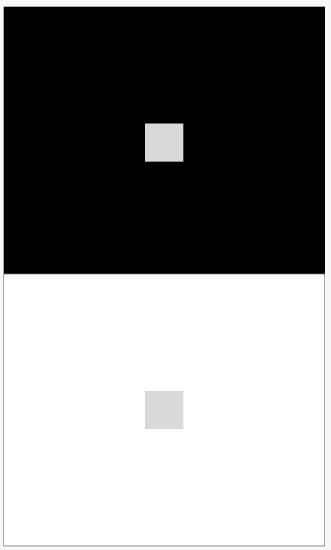

|

Even with all the white on this page, it is difficult to tell how dark that little square is when it is on a dark background. It is much easier to see when the same square is on a white background. By the way, did you notice that all of the pages of this book are not actually white? Probably not, since in most PDF viewers there is nothing which to compare (key) the white. |

DID YOU...

Set your Lightroom background to white and adjust the brightness of your display?

Notice how I repeat some things a lot?

CAN YOU...

Make an adjustment to one image, then apply that adjustment to other images?

Print an image?

Still do everything covered in the previous Lightroom instructions (1lr)?

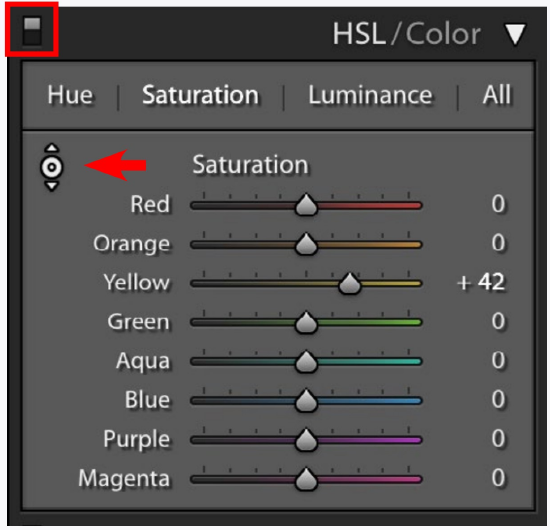

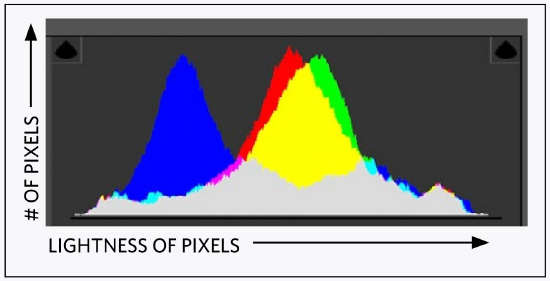

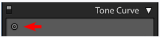

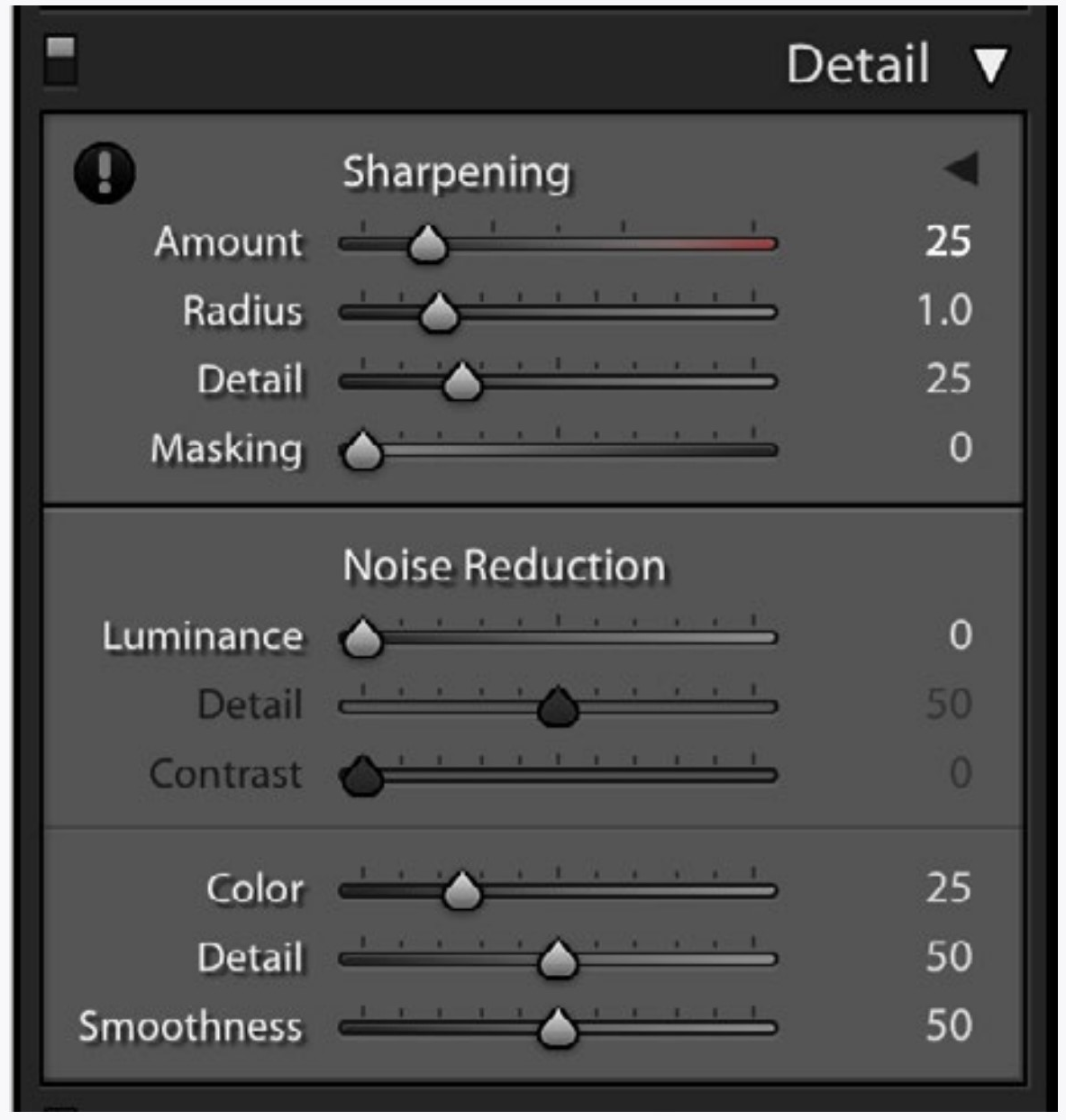

3LR HISTOGRAM

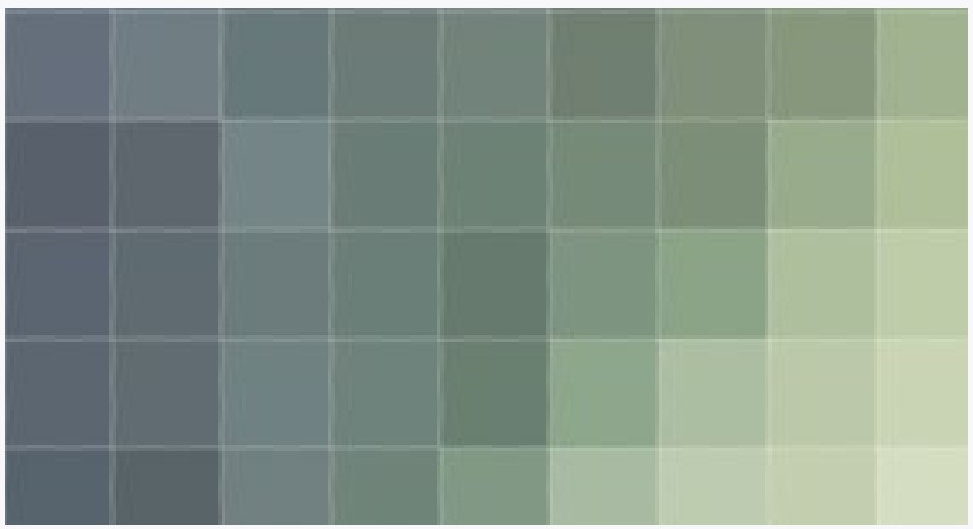

Every digital photograph is made up small squares called pixels (a shortening of picture elements). You don’t normally see these because they are too small in most viewing situations. Each of these pixels is only one color. When there are enough of them (they are small enough) your eyes see these not as squares, but as continuous tone and color.

When editing photographs individual pixels don’t matter too much, but how the pixels work together does matter.

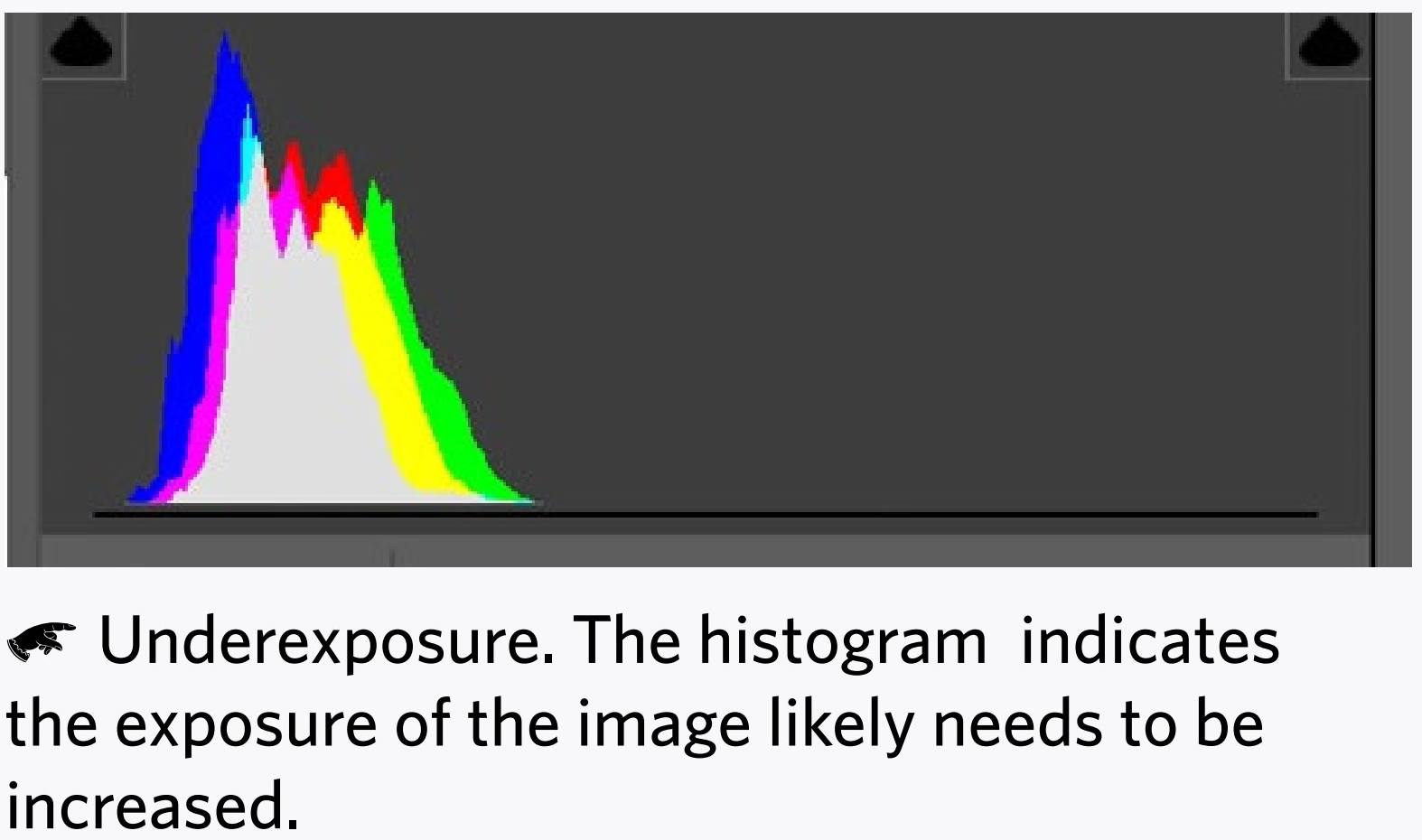

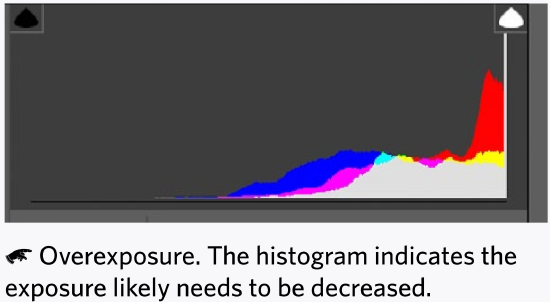

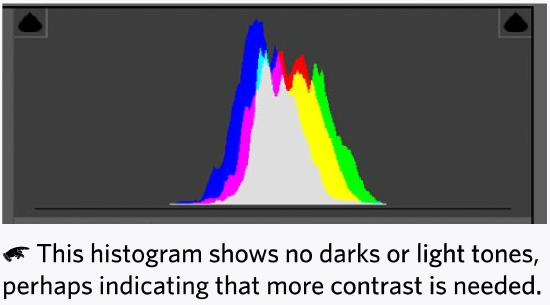

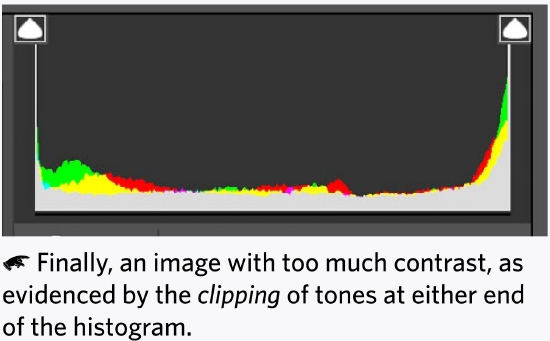

The histogram is a map that shows the pixels working together. The number of pixels of a certain tone give the hills height, and the tone of the pixels give it width, with the darker pixels on the left and lighter on the right. It is an essential tool that shows us another perspective and can illuminate problems with images.

The Lightroom histogram shows the levels of each of the three primary colors of the pixels.

Proof of how important histograms are is the fact that you see them in any image editing application, and even as a display option on your camera.

Good photographs can be very dark, very light, or have a lot of clipping. But the histogram helps you to be intentional about what you are doing.

3LR TONAL ADJUSTMENTS

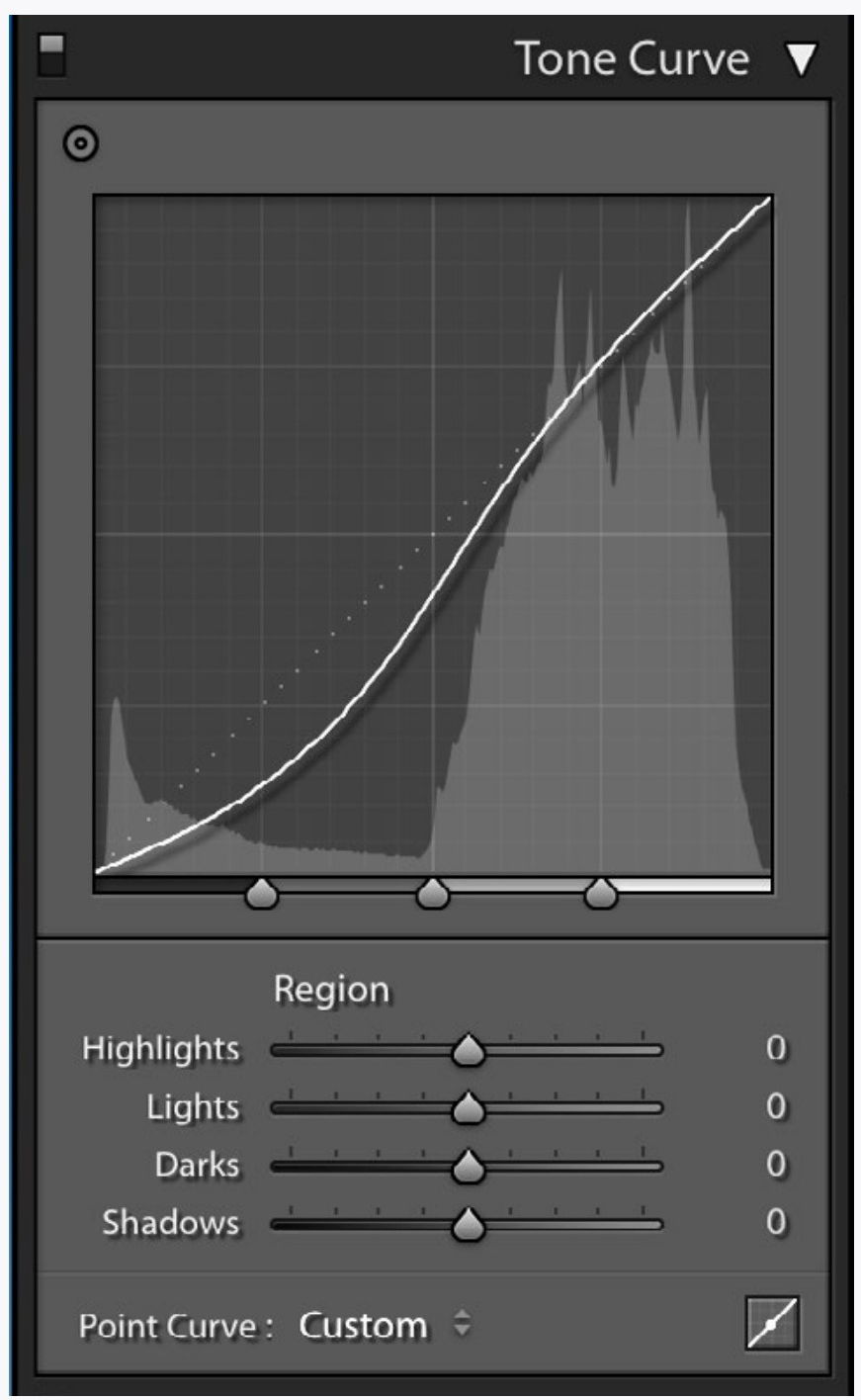

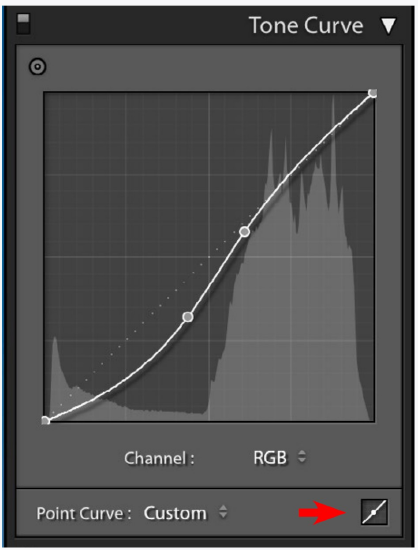

Before adjusting the following options in Lightroom, first adjust White Balance, Exposure, and Contrast.

Here is when you adjust the others:

Highlights

These are the lighter tones (or colors) in an image. After you adjust the brightness and contrast, sometimes you will find that the lighter areas in the image are too light and so without detail. Bringing down the highlights will correct for this.

Shadows

These are the darker tones (or colors) in an image. If they are too dark without detail, you can lighten them to correct for this.

Less often with both highlights and shadows, you may need to adjust the other way. Such as if the highlights are too dark or the shadows too light.

Whites

These are the very light areas of the image. Be careful adjusting these since all of the spark of an image can be dulled with too low a setting and all detail lost with too high of a setting.

Blacks

The very darkest tones. Making them too light will render the darkest areas gray and muddy, so be careful with this adjustment also.

Texture

The edges of small repeating details are sharpened to enhance the impression of texture.

Clarity

Clarity is like contrast, but works at a more detailed level. As with all the adjustments, try the extremes to see what they do.

Vibrance

Vibrance is like saturation, but protects skin tones and already saturated colors from getting too saturated.

Saturation

Saturation is how intense the colors appear. With no saturation you have a black and white image, and with a lot of saturation the colors ‘pop’ unnaturally. This is a common control, and since contrast also effects saturation, it is often needed when you make a contrast change.

Saturation, along with exposure, contrast, and white balance work linearly on the image, while the other adjustments use a bit more ‘intelligence’, which can lead to a very artificial look when used without discretion.

|

(Dehaze is not a commonly used adjustment) |

3LR USING THE CONTROLS

HISTOGRAM

You may notice that histograms on cameras are dealt with in Chapter 6 of this text. The histograms in Lightroom are basically the same, but they are more immediately useful when editing images. That is why they are introduced here first.

Get used to looking at histograms as you adjust images. They help you see what is happening to the tones of an image, and so are very important. As you get better at the controls they will become even more helpful... but only if you know how to use them.

TONAL ADJUSTMENTS

Most students tend to drag the more advanced controls discussed here wily-nilly in strange ways. Be intentional!

|

Lightroom comparison view showing difference of only shadows adjustment |

In other words, do the basic exposure and contrast adjustments first, then invoke the others only as you need to. So, if you adjust the exposure and contrast, then find you need the shadows to be lighter, only then use the shadows slider (see example of this below). Adjust the same way for the other controls.

This is a good time for you to review how to compare images side by side (1lr) so you can see exactly what is happening when you make an adjustment. Just make one adjustment at a time (then reset it) to see what each slider does.

All of this takes practice. I wish I could tell you how to use any control in Lightroom and suddenly you would know how and when to use it, but it doesn’t work that way. Practice is the only way to learn these controls. This book only gets you started.

CAN YOU...

Understand the basics of what a histogram is showing about your image?

Predict the contrast and exposure needs of an image just from the histogram?

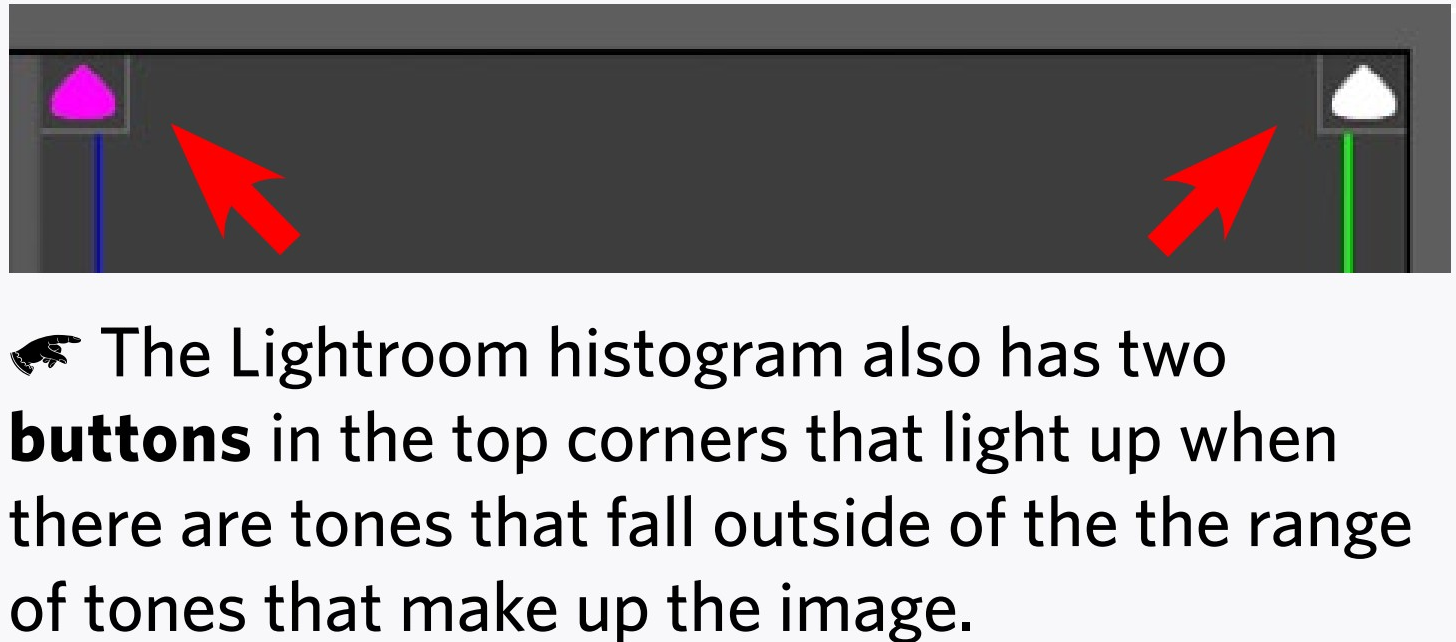

Turn on and off the clipping buttons to see the tones outside areas of an image?

Understand the function of all the sliders in the basic tab of Lightroom?

Identify and change the sliders by dragging directly on the histogram?

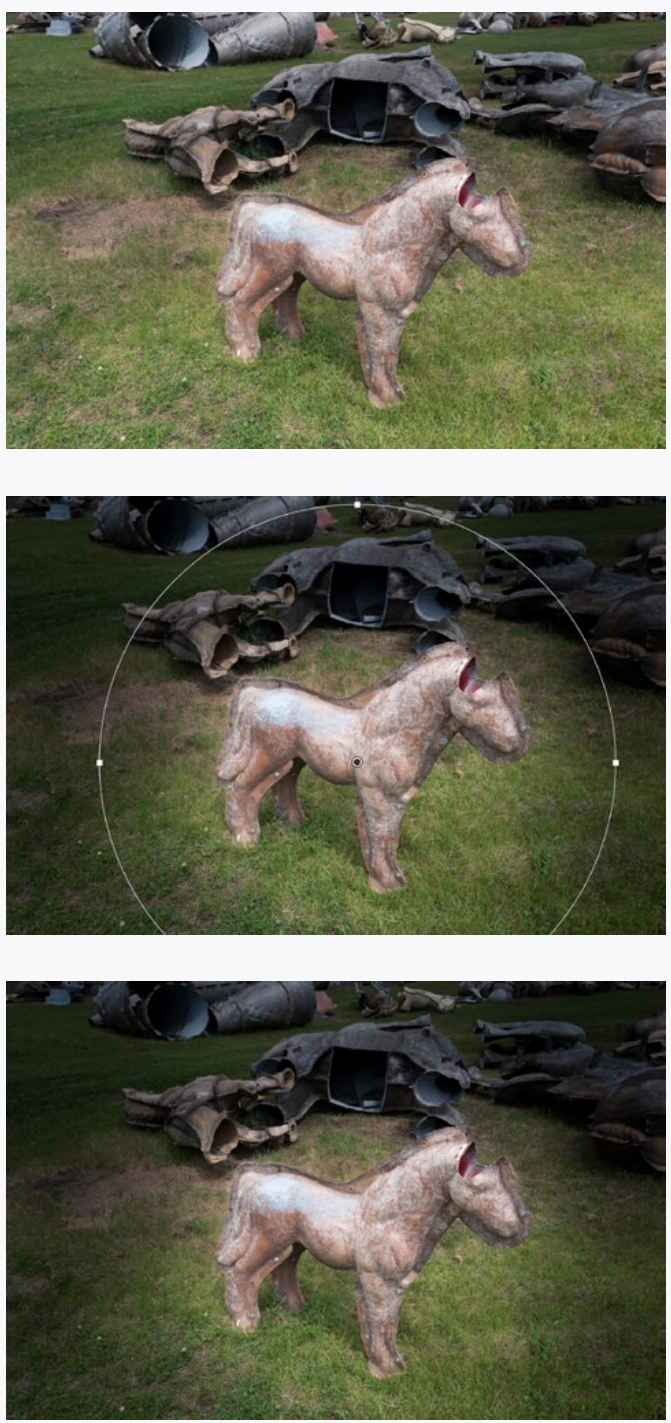

4LR LOCAL ADJUSTMENTS

|

Trevor Finchcamp, before local adjustments |

Trevor Finchcamp, after local adjustments to darken the top area of the image and lighten and increase contrast on bottom |

|

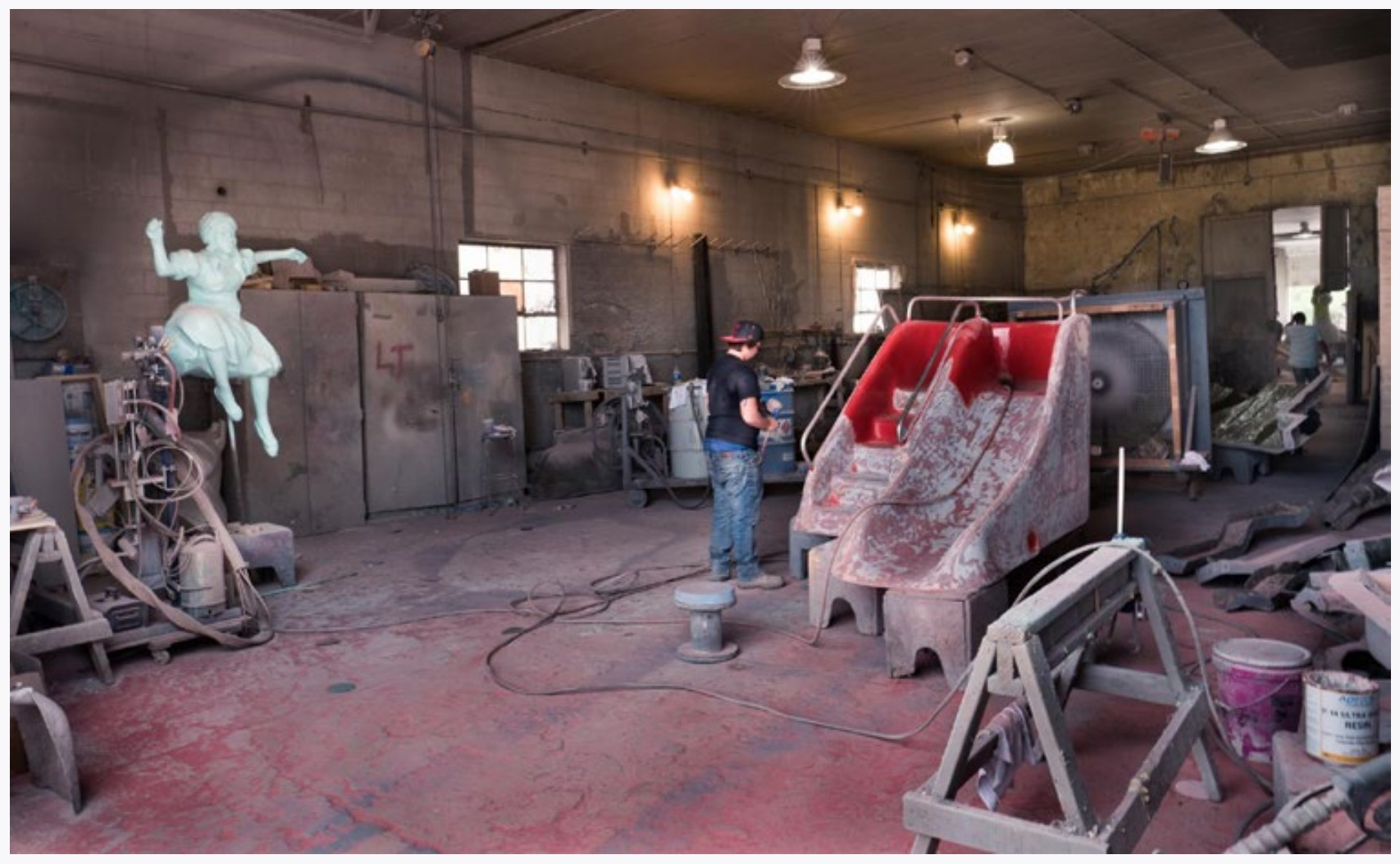

Original image |

Background area was lightened and foreground area darkened. The sculpture on the left was lightened more by using auto mask (next page). |

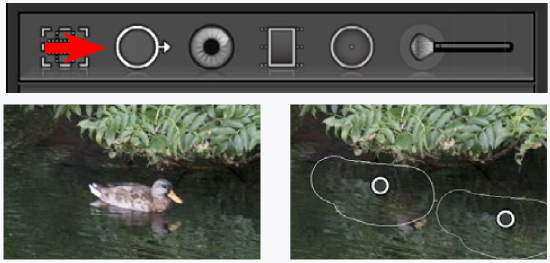

4LR MASKS

A Mask in Lightroom is simply a selected area. When you are painting in adjustments, you can turn on the mask right below the image.

This will allow you to see the areas you are painting with a color overlay. Showing the mask is simply a viewing aid —it will not change the image.

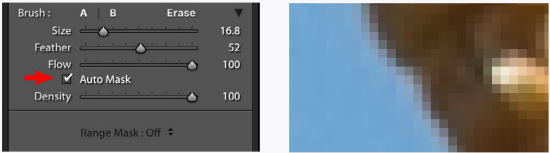

Auto Mask

Much different than this mask is the Auto Mask. When turned on (red arrow below), the adjustments brush will attempt to find boundaries in the image and constrain the painting to within those boundaries. This is the way you use the adjustments brush to adjust things instead of areas in the image.

Often when using auto mask you should first paint along the edges of the thing you want adjusted, then turn off Auto Mask to paint in the rest of the thing to be selected for adjustment.

Painting and erasing (also using auto mask) at enlarged views is a way to refine the edge, and you may have to repeat this several times to get the right masking edge.

Auto mask does have its limits. Edges in images are not clear cut, and often include transition pixels that are neither the color of the object nor of the background.

In general, do not expect to make radical adjustments using auto mask to define things.

The image above shows the red mask defining areas painted while using Auto Mask on the right and a darkened sky on the left. While auto mask does a good job in large areas with definite borders (the beak), it has a very difficult job selecting smaller areas and areas with less defined edges (like the small feathers on the top of the bird’s head).

Hard edges are actually composed of transition pixels (below right) which can cause problems with extreme adjustments when using the auto mask.

4LR USING THE CONTROLS

LOCAL ADJUSTMENTS

Being able to adjust only parts of an image is a powerful technique, but one that takes a lot of practice. You might as well get started now.

Pick some images that might need an adjustment in areas that is different from the overall adjustments, and see what you can do. Make things lighter, darker, and maybe increase the contrast. Try changing the color of an area using the white balance tools at the top of the adjustment brush panel. Try to instead change the color using the Hue slider.

Perhaps find some images that don’t need obvious adjustments. Can you improve the image using them? In general, lighter areas draw the viewer’s eye and darker areas recede. Can you use this fact to control the way the viewer sees elements in the image?

Experiment. As always, view your changes side by side with the unchanged version to compare them.

AUTO MASK

Use auto mask to limit your local adjustments to just one thing in the image, such as the sky, or perhaps a person’s face which is too dark in relation to the rest of the image.

Get the hang of how accurate auto mask can be by enlarging the adjusted image to 1:1 (100%) to view it. In general the heavier the adjustment the more accurate auto mask needs to be.

Small section of a photograph before and after the sky was darkened with the adjustment brush using auto mask. The transition line along the horizon is very obvious on the adjusted image. Auto mask does have limitations, especially with the heavy adjustment seen here.

Two options to hide this limitation would be to make the adjustment not as extreme or make the photograph (and therefore the imperfections) smaller—as shown at right.

CAN YOU...

Effectively change only parts of an image?

Make your local adjustments seem natural?Erase and add to portions of your adjustments?Use appropriate brush sizes and feathers?