5.1: A beginner's guide to Contemporary Art

- Page ID

- 107383

Contemporary Art, an introduction

“Getting” Contemporary Art

It’s ironic that many people say they don’t “get” contemporary art because, unlike Egyptian tomb painting or Greek sculpture, art made since 1960 reflects our own recent past. It speaks to the dramatic social, political and technological changes of the last 50 years, and it questions many of society’s values and assumptions—a tendency of postmodernism, a concept sometimes used to describe contemporary art. What makes today’s art especially challenging is that, like the world around us, it has become more diverse and cannot be easily defined through a list of visual characteristics, artistic themes or cultural concerns.

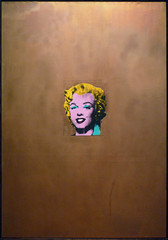

Minimalism and Pop Art, two major art movements of the early 1960s, offer clues to the different directions of art in the late 20th and 21st century. Both rejected established expectations about art’s aesthetic qualities and need for originality. Minimalist objects are spare geometric forms, often made from industrial processes and materials, which lack surface details, expressive markings, and any discernible meaning. Pop Art took its subject matter from low-brow sources like comic books and advertising. Like Minimalism, its use of commercial techniques eliminated emotional content implied by the artist’s individual approach, something that had been important to the previous generation of modern painters. The result was that both movements effectively blurred the line distinguishing fine art from more ordinary aspects of life, and forced us to reconsider art’s place and purpose in the world.

Shifting Strategies

Minimalism and Pop Art paved the way for later artists to explore questions about the conceptual nature of art, its form, its production, and its ability to communicate in different ways. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these ideas led to a “dematerialization of art,” when artists turned away from painting and sculpture to experiment with new formats including photography, film and video, performance art, large-scale installations and earth works. Although some critics of the time foretold “the death of painting,” art today encompasses a broad range of traditional and experimental media, including works that rely on Internet technology and other scientific innovations.

Contemporary artists continue to use a varied vocabulary of abstract and representational forms to convey their ideas. It is important to remember that the art of our time did not develop in a vacuum; rather, it reflects the social and political concerns of its cultural context. For example, artists like Judy Chicago, who were inspired by the feminist movement of the early 1970s, embraced imagery and art forms that had historical connections to women.

In the 1980s, artists appropriated the style and methods of mass media advertising to investigate issues of cultural authority and identity politics. More recently, artists like Maya Lin, who designed the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial Wall in Washington D.C., and Richard Serra, who was loosely associated with Minimalism in the 1960s, have adapted characteristics of Minimalist art to create new abstract sculptures that encourage more personal interaction and emotional response among viewers.

These shifting strategies to engage the viewer show how contemporary art’s significance exists beyond the object itself. Its meaning develops from cultural discourse, interpretation and a range of individual understandings, in addition to the formal and conceptual problems that first motivated the artist. In this way, the art of our times may serve as a catalyst for an on-going process of open discussion and intellectual inquiry about the world today.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

How to Learn About Contemporary Art

by The Art Assignment

The YBAs: The London-based Young British Artists

by ROSE AIDIN

“Young British Artists” (or YBAs as they swiftly became known) is now something of a misnomer. For this group of artists can no longer be described as young—they are mostly now in their fifties—and they are very international, and barely share a common style. Yet this small group of London-based artists, who came to prominence in the nineties, changed the international art world. The YBA phenomenon directly contributed to the climate of acceptance of modern and contemporary art in the U.K. which enabled the success of Tate Modern when it opened in 2000. The YBA remain a powerful force in the international art world today.

I first encountered the Young British Artists as a freelance journalist covering the arts for the mainstream press in the late nineties. By then art was no longer confined to single column reviews in remote arts pages, as it had been for decades. Instead, contemporary art was splashed over front and features pages. The Tate’s annual Turner Prize for contemporary art had become headline news, with the award ceremony broadcast live on television, and for an intoxicating time, London was the center of the international creative world—all thanks largely to the YBAs.

So who and what are the YBAs?

The YBAs were a loose and disparate group, very much associated with London in the 1990s and the period of increased pride in popular British culture dubbed “Cool Britannia.” YBA artists included Jake and Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Sarah Lucas, Chris Ofili, Marc Quinn, Sam Taylor-Johnson, Mark Wallinger, and Rachel Whiteread. Many of the artists had studied together at Goldsmiths College of Art in London, which had abolished the traditional separation between art forms (painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking) and focused on conceptual art, however there is no one single YBA style or approach. The work can be shocking, conceptual, or even traditional in its formal features: the principal link between the YBAs was social and attitudinal.

The majority of the artists came from non-establishment backgrounds, had grown up with Margaret Thatcher as prime minister and, perhaps as a result, had acquired an entrepreneurial, “can-do” approach to art and life. Then in their twenties and thirties, these artists were often glamorous and generally loved to party, and the nineties art world—and “Cool Britannia”—was happy to give them free rein.

Damien Hirst, Freeze, and Charles Saatchi

So how did the YBAs come into being? Damien Hirst was de facto ringleader of the YBAs. In 1988, while studying at Goldsmiths College, Hirst curated and promoted a “pop up” exhibition in an empty warehouse of work by him and his peers, entitled Freeze. Charles Saatchi, an advertising titan and art collector, bought work from Hirst’s Freeze show and from the fledging artists’ representatives. In 1992, the phrase “Young British Artists” was first used by Art Forum magazine to describe the group, and when Saatchi exhibited their work at his 30,000 square foot space in a converted paint factory in North London that same year, he entitled the show Young British Artists. And so a new movement was born. The work was new, fresh, and exciting: immediately accessible to the public, yet also with high art resonances and references.

The most expensive fish without chips

Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living of 1991, a shark suspended and preserved in a tank of formaldehyde, looked sensational in the Saatchi Gallery’s warehouse-style setting in the 1992 Young British Artists exhibition. The Sun tabloid newspaper ran a story about the piece entitled “£50,000 for fish without chips?” and “the shark” became an icon of nineties art and culture. As a result, Hirst was shortlisted for that year’s Turner Prize, and in 1995 was awarded the prize, which was presented to him by Charles Saatchi. The YBA star was firmly in the ascendant.

Hirst’s Turner Prize exhibition included Mother and Child Divided (1993), a cow and calf cut in half and preserved in a vitrine of formaldehyde. The work caused outrage among the animal-loving British public. Hirst commented, “I remember what Warhol said: you don’t read your reviews, you weigh them.” He might well have added another of Warhol’s aphorisms: “Making money is art. And working is art. And good business is the best art.”

YBAs at the heart of the establishment

It was Charles Saatchi again, master of both presentation and media coverage, who positioned the YBAs firmly in the mainstream of popular culture with the 1997 exhibition Sensation, which filled the Royal Academy in London with 110 works by 42 artists from Saatchi’s personal collection. It was the year that Princess Diana died and Tony Blair became Prime Minister. The country was ripe for a change. The YBA’s column inches became column miles: the exhibition was visited by 285,000 people, almost half of them aged under thirty. A new audience and climate had been created for modern art. Contemporary art was now at the fore of public consciousness.

The path to Tate Modern

Until Tate Modern opened in 2000, London was the only major European city without a public art gallery for modern and contemporary art. Britain was resolutely philistine about the visual as epitomized by a controversy in 1976 triggered by the display of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966) as a recent acquisition at the Tate Gallery in Millbank (now Tate Britain). The Evening Standard referred to the sculpture as a “pile of bricks.” Public outrage and protest focused on the expenditure of “tax payers’ money” on this Minimalist work made of manufactured bricks. Evidently, much needed to change before a museum of modern art would be welcome in London. Private funds would be required in order for public collections to acquire modern and contemporary art, and ultimately to support a London museum dedicated to its display.

In 1984 the Tate’s annual Turner Prize for new art was founded with the long-term goal of creating an open and understanding climate for modern and contemporary art. By the mid-nineties, thanks to the nominated Young British Artists’ high profile and pulling power, the Turner Prize had become a major annual event, with record-breaking numbers of visitors to the Tate’s exhibition of short-listed artists, and its gala dinners and prize-giving ceremonies avidly attended and covered, with the likes of Madonna presenting the prize. The purpose of the Turner Prize was accomplished, thanks in great part to the YBAs, and the public made ready for the opening of Tate Modern.

“Art is power”

When Tate Modern (a museum dedicated to modern and contemporary art) opened in London in May 2000, its launch party for 4,000 people was the hottest ticket in town, and broadcast live on the BBC. Invitations were said to be changing hands for up to £1,000 and some left town rather than admit they were not on the list. “Everyone” was there, yet it was the Young British Artists who had done so much with their talent, energy and glamour to bring the art world’s focus to London for the first time in centuries (and to create a climate of acceptance for contemporary art), who provided the stardust. The YBAs ensured that Tate Modern’s opening party was the place to be and the museum was an instant success, with visitor numbers vastly higher than anticipated.

As the artistic duo Gilbert & George said as they opened the building earlier that day in front of the Queen of England, “Art is power.” The YBAs ruled the establishment: the artists were celebrities and everyone wanted to know more about them. And that, for a while, was how I made my living. Then it all suddenly came to an end, with 9/11 as a marker. Shortly after the twin tower attacks, Charles Saatchi closed the private gallery that had done so much to incubate the YBA movement, and there was a sense of moving on. I went into teaching and now teach the work of many of the artists I interviewed. The young adults I teach are consistently fascinated by the YBAs’ work, which speaks very strongly to them, and convinces me that even now—long after the parties and the scene have faded—the work itself will endure and stand the test of time.

Additional resources:

Tate on the Young British Artists

Damien Hirst: Art and Life (video)

The Saatchi Gallery on Sensation at the Royal Academy

Tate archive on Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII and the “Bricks controversy”

Tate archive on the opening of Tate Modern

Rose Aidin, “The Comeback King,” The Saturday Telegraph Magazine (October 2, 2001)

Rose Aidin, “Brit Art’s square dealer moves on,” The Guardian (September 22, 2002)

“Tate Gallery Buys Pile of Bricks—Or Is It Art?,” The New York Times (February 20, 1976)