13.3.1: A beginner's guide

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88683

Introduction to Islam

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Origins and the life of Muhammad the Prophet

Islam, Judaism and Christianity are three of the world’s great monotheistic faiths. They share many of the same holy sites, such as Jerusalem, and prophets, such as Abraham. Collectively, scholars refer to these three religions as the Abrahamic faiths, since Abraham and his family played vital roles in the formation of these religions.

Islam was founded by Muhammad (c. 570-632 C.E.), a merchant from the city of Mecca, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Mecca was a well-established trading city. The Kaaba (in Mecca) is the focus of pilgrimage for Muslims.

The Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, provides very little detail about Muhammad’s life; however, the hadiths, or sayings of the Prophet, which were largely compiled in the centuries following Muhammad’s death, provide a larger narrative for the events in his life. Muhammad was born in 570 C.E. in Mecca, and his early life was unremarkable. He married a wealthy widow named Khadija. Around 610 C.E., Muhammad had his first religious experience, where he was instructed to recite by the Angel Gabriel. After a period of introspection and self-doubt, Muhammad accepted his role as God’s prophet and began to preach word of the one God, or Allah in Arabic. His first convert was his wife.

Muhammad’s divine recitations form the Qur’an; unlike the Bible or Hindu epics, it is organized into verses, known as ayat. During one of his many visions, in 621 C.E., Muhammad was taken on the famous Night Journey by the Angel Gabriel, travelling from Mecca to the farthest mosque in Jerusalem, from where he ascended into heaven. The site of his ascension is believed to be the stone around which the Dome of the Rock was built. Eventually in 622, Muhammad and his followers fled Mecca for the city of Yathrib, which is known as Medina today, where his community was welcomed. This event is known as the hijra, or emigration. 622, the year of the hijra (A.H.), marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar, which is still in use today.

Between 625-630 C.E., there were a series of battles fought between the Meccans and Muhammad and the new Muslim community. Eventually, Muhammad was victorious and reentered Mecca in 630.

One of Muhammad’s first actions was to purge the Kaaba of all of its idols (before this, the Kaaba was a major site of pilgrimage for the polytheistic religious traditions of the Arabian Peninsula and contained numerous idols of pagan gods). The Kaaba is believed to have been built by Abraham (or Ibrahim as he is known in Arabic) and his son, Ishmael. The Arabs claim descent from Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar. The Kaaba then became the most important center for pilgrimage in Islam.

In 632, Muhammad died in Medina. Muslims believe that he was the final in a line of prophets, which included Moses, Abraham, and Jesus.

After Muhammad’s death

The century following Muhammad’s death was dominated by military conquest and expansion. Muhammad was succeeded by the four “rightly-guided” Caliphs (khalifa or successor in Arabic): Abu Bakr (632-34 C.E.), Umar (634-44 C.E.), Uthman (644-56 C.E.), and Ali (656-661 C.E.). The Qur’an is believed to have been codified during Uthman’s reign. The final caliph, Ali, was married to Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter and was murdered in 661. The death of Ali is a very important event; his followers, who believed that he should have succeeded Muhammad directly, became known as the Shi’a, meaning the followers of Ali. Today, the Shi’ite community is composed of several different branches, and there are large Shi’a populations in Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain. The Sunnis, who do not hold that Ali should have directly succeeded Muhammad, compose the largest branch of Islam; their adherents can be found across North Africa, the Middle East, as well as in Asia and Europe.

During the seventh and early eighth centuries, the Arab armies conquered large swaths of territory in the Middle East, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Central Asia, despite on-going civil wars in Arabia and the Middle East. Eventually, the Umayyad Dynasty emerged as the rulers, with Abd al-Malik completing the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest surviving Islamic monuments, in 691/2 C.E. The Umayyads reigned until 749/50 C.E., when they were overthrown, and the Abbasid Dynasty assumed the Caliphate and ruled large sections of the Islamic world. However, with the Abbasid Revolution, no one ruler would ever again control all of the Islamic lands.

Additional resources:

The Birth of Islam on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

World Religions in Art: Islam (from the Minneapolis Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

About chronological periods in the Islamic world

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Studying the art of the Islamic world is challenging, partially because of the large geographic and chronological scope of Islam. Islam has been a major religion and cultural force for over fourteen centuries and continues to be so today. At present the Arts of the Islamic World Section is organized into three chronological periods: Early, Medieval and Late. These chronological divisions are modern creations that help scholars to organize information and works of art to interpret them better. It also helps students to understand how works of art and architecture relate to each other in time and space. There were dynasties and empires that controlled different lands and whose periods of rule stretched across these chronological divisions.

Early period (c. 640-900 C.E.)

After Muhammad’s death in 634, there were four caliphs later referred to by the Sunni as “rightfully guided,” who succeeded Muhammad. However, from 656 there were conflicts over succession, and two civil wars (656-661 and 680-692) broke out within the community of Muslims. Out of these wars emerged the Umayyad Dynasty, whose capital was Damascus in modern-day Syria. Responsible for the first great monuments of Islamic art and architecture, Umayyad rulers built the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the Great Mosque of Damascus, and the so-called Desert Palaces in Syro-Palestine . The Umayyads ruled as caliphs until 750 C.E., when they were overthrown by the Abbasids. The Abbasids, like the Umayyads before them, ruled as caliphs over much of the Islamic world until 861. Their capital was at Baghdad, and later they ruled from the palace-city of Samarra in Iraq for parts of the ninth century. After 861, the Abbasids lost control of large parts of their empire through a series of uprisings in which provincial governors asserted their independence. A series of local dynasties, such as the Aghlabids (800-909) and Tulunids (868-905) in North Africa, and the Buyids (945-1055) in Central Asia, emerged and ruled, developing regional artistic styles.

Medieval period (c. 900-1517 C.E.)

By the tenth century, there was fragmentation and individual dynasties sprang up. These dynasties had varying degrees of control over different parts of the lands where Islam was the dominant or a major religion.

In North Africa and the Near East, certain major dynasties, such as the Fatimids (909-1171), emerged and ruled an area that includes present-day Egypt, Sicily, Algeria, Tunisia, and parts of Syria. It is also at this time that some of the major Turkic dynasties and people from Central Asia came to the forefront of politics and artistic creativity in the Islamic world. The Seljuqs were Central Asian nomads who ruled eastern Islamic lands and eventually controlled Iran, Iraq and much of Anatolia, although this empire was short-lived. The main branch of the Seljuqs, the Great Seljuqs, maintained control over Iran.

It was also the time of the European Christian crusades, which aimed to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. A series of small Christian Kingdoms emerged in the twelfth century, as did Muslim dynasties, such as the Ayyubids (1179-1260), whose most famous leader, Salah al-Din (r.1169-93), known in Europe as Saladin, ended the Fatimid dynasty. Eventually the slave soldiers, upon whom the Ayyubid dynasty depended for their military protection, overthrew the last Ayyubid sultan in 1249/50. These slaves, known in Arabic as mamluk, literally meaning “owned,” became known as the Mamluks and they controlled Syria and Egypt until 1517.

The Mamluks also had to face one of the greatest threats to their reign early on: The invading Mongols. The Mongols and their great leader, Genghis Khan (c. 1162-1227), are almost always associated with blood-thirsty conquest and destruction, but his legacy included the Yuan dynasty in China (1279-1368), the Chaghatay khanate in Central Asia (c. 1227–1363), the Golden Horde in southern Russia, extending into Europe (ca. 1227–1502), and the Ilkhanid dynasty in Greater Iran (1256–1353). The Pax Mongolica (“Mongolian Peace”) includes a great flowering of the arts.

The Ilkhanids, who ruled over Iran, parts of Iraq and Central Asia, oversaw great artistic development in manuscripts, such as those that recounted the Shahnama (or Book of Kings), the famous Persian epic. They were important patrons of architecture. The Ilkhanid dynasty disintegrated in 1335 and local dynasties came to power in Iraq and Iran.

In 1370, the last great dynasty emerged from Central Asia: the Timurids (c. 1370-1507). They were named for their leader, Timur (also known as Tamerlane), who conquered and controlled all of Central Asia, greater Iran, and Iraq, as well as parts of southern Russia and the Indian subcontinent. The Timurids were outstanding builders of monumental architecture. Herat, in present-day Afghanistan, became the capital and cultural center of the Timurid empire.

While artistic production and architecture flourished in Asia under different Islamic dynasties, it also bloomed in the western Islamic lands. The most famous of these dynasties is probably the Nasrids (1232-1492) of the southern Iberian Peninsula and western North Africa, whose most important artistic achievement is the remarkable Alhambra, a palace-fortress complex in Granada, in present-day Spain.

Later period (c. 1517–1924 C.E.)

This period is the era of the last great Islamic Empires. The Ottoman Empire, which had started as a small Turkic state in Anatolia in the early fourteenth century, emerged in the second half of the fifteenth century as a major military and political force. The Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 and the Mamluk Empire in 1517. They dominated much of Anatolia, the Balkans, the Near East and North Africa until the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. The Ottomans are famous for their domed architecture and pencil minarets, many of which were built by the great architect, Sinan (1539–1588) for Sultan Süleyman (r. 1520–66). This period is considered the peak of Ottoman art and culture.

The Safavids, who established Shia Islam as the dominant faith of Iran, ruled from 1501–1722 and were the greatest dynasty to emerge from Iran. Architecture, paintings, manuscripts and carpets all flourished under the Safavids. Shah Abbas (r. 1587–1629) was the greatest patron of the arts and the Safavid Dynasty’s most outstanding ruler. In the eighteenth century, a period of turmoil in Persia, the Qajar dynasty (1779–1924) rose to power and established peace and their rule saw the beginning of modernity in Iran.

The other great dynasty that oversaw a remarkable artistic and architectural output was the Mughals. Founded by Babur, the Mughals (c. 1526–1858) ruled over the largest Islamic state in the Indian subcontinent. While there had been earlier sultanates in what is today northern Indian and Pakistan, the emperors of the Mughal dynasty were patrons of some of the greatest works of Islamic art, such as illuminated manuscripts and painting, and architecture, including the Taj Mahal.

Additional resources:

Islamic art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Arts of the Islamic world

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

What is Islamic Art?

The Dome of the Rock, the Taj Mahal, a Mina’i ware bowl, a silk carpet, a Qur‘an; all of these are examples of Islamic Art. But what is Islamic Art?

Islamic Art is a modern concept, created by art historians in the nineteenth century to categorize and study the material first produced under the Islamic peoples that emerged from Arabia in the seventh century.

Today Islamic Art describes all of the arts that were produced in the lands where Islam was the dominant religion or the religion of those who ruled. Unlike the terms Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist art, which refer only to religious art of these faiths, Islamic art is not used merely to describe religious art or architecture, but applies to all art forms produced in the Islamic World.

Thus, Islamic Art refers not only to works created by Muslim artists, artisans, and architects or for Muslim patrons. It encompasses the works created by Muslim artists for a patron of any faith, including Christians, Jews, or Hindus, and the works created by Jews, Christians, and others, living in Islamic lands, for patrons, Muslim and otherwise.

One of the most famous monuments of Islamic Art is the Taj Mahal, a royal mausoleum, located in Agra, India. Hinduism is majority religion in India; however, because Muslim rulers, most famously the Mughals, dominated large areas of modern-day India for centuries, India has a vast range of Islamic art and architecture. The Great Mosque of Xian, China, is one of the oldest and best preserved mosques in China. First constructed in 742 C.E., the mosque’s current form dates to the fifteenth century C.E. and follows the plan and architecture of a contemporary Buddhist temple. In fact, much Islamic art and architecture was—and still is—created through a synthesis of local traditions and more global ideas.

Islamic Art is not a monolithic style or movement; it spans 1,300 years of history and has incredible geographic diversity—Islamic empires and dynasties controlled territory from Spain to western China at various points in history. However, few if any of these various countries or Muslim empires would have referred to their art as Islamic. An artisan in Damascus thought of his work as Syrian or Damascene—not as Islamic.

As a result of thinking about the problems of calling such art Islamic, certain scholars and major museums, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have decided to omit the term Islamic when they renamed their new galleries of Islamic art. Instead, they are called “Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia,” thereby stressing the regional styles and individual cultures. Thus, when using the phrase, Islamic Art, one should know that it is a useful, but artificial, concept.

In some ways, Islamic Art is a bit like referring to the Italian Renaissance. During the Renaissance, there was no unified Italy; it was a land of independent city-states. No one would have thought of one’s self as an Italian, or of the art they produced as Italian, rather one conceived of one’s self as a Roman, a Florentine, or a Venetian. Each city developed a highly local, remarkable style. At the same time, there are certain underlying themes or similarities that unify the art and architecture of these cities and allow scholars to speak of an Italian Renaissance.

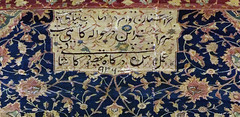

Themes

Similarly, there are themes and types of objects that link the arts of the Islamic World together. Calligraphy is a very important art form in the Islamic World. The Qur’an, written in elegant scripts, represents Allah’s (or God’s) divine word, which Muhammad received directly from Allah during his visions. Quranic verses, executed in calligraphy, are found on many different forms of art and architecture. Likewise, poetry can be found on everything from ceramic bowls to the walls of houses. Calligraphy’s omnipresence underscores the value that is placed on language, specifically Arabic.

Geometric and vegetative motifs are very popular throughout the lands where Islam was once or still is a major religion and cultural force, appearing in the private palaces of buildings such as the Alhambra (in Spain) as well as in the detailed metal work of Safavid Iran. Likewise, certain building types appear throughout the Muslim world: mosques with their minarets, mausolea, gardens, and madrasas (religious schools) are all common. However, their forms vary greatly.

One of the most common misconceptions about the art of the Islamic World is that it is aniconic; that is, the art does not contain representations of humans or animals. Religious art and architecture, almost from the earliest examples, such as the Dome of the Rock, the Aqsa Mosque (both in Jerusalem), and the Great Mosque of Damascus, built under the Umayyad rulers, did not include human figures and animals. However, the private residences of sovereigns, such as Qasr ‘Amra or Khirbat Mafjar, were filled with vast figurative paintings, mosaics, and sculpture.

The study of the arts of the Islamic World has also lagged behind other fields in Art History. There are several reasons for this. First, many scholars are not familiar with Arabic or Farsi (the dominant language in Iran). Calligraphy, particularly Arabic calligraphy, as noted above, is a major art form and appears on almost all types of architecture and arts. Second, the art forms and objects prized in the Islamic world do not correspond to those traditionally valued by art historians and collectors in the Western world. The so-called decorative arts—carpets, ceramics, metalwork, and books—are types of art that Western scholars have traditionally valued less than painting and sculpture. However, the last fifty years has seen a flourishing of scholarship on the arts of the Islamic World.

Arts of the Islamic World

Here, we have decided to use the phrase “Arts of the Islamic World” to emphasize the art that was created in a world where Islam was a dominant religion or a major cultural force, but was not necessarily religious art. Often when the word “Islamic” is used today, it is used to describe something religious; thus using the phrase, Islamic Art, potentially implies, mistakenly, that all of this art is religious in nature. The phrase, “Arts of the Islamic World,” also acknowledges that not all of the work produced in the “Islamic World” was for Muslims or was created by Muslims.

Note on organization from the contributing editor

We have organized the material in this section into three chronological periods: Early, Medieval and Late. When starting to learn about a new area of art, chronological organization often enables students to grasp the material and its fundamentals before going on to more complex analysis, like comparing building types or styles. Within each of these chronological groups, we have focused on creating geographic groups or groupings to organize the material further. The Islamic World was only unified very briefly in its history under the Umayyads (661-750 CE) and the early Abbasids (750-932 CE). Soon various dynasties or rulers simultaneously commanded sections of territory, many of which had no cultural commonalities, aside from their religion.

We are also planning to upload a series of introductory essays on major types of art and architecture from the Islamic World, including carpets and mosques, in addition to essays and videos about specific works of art and architecture. These are forthcoming.

Arabic, Persian and Turkish are complex languages whose transcription from their respective scripts to English has changed considerably over time. For the sake of ease, we have used the most common forms today, omitting the vocalizations. While we have aimed for consistency, we have also tried to use the simplest forms for those who are new to the arts of the Islamic World.

Additional resources:

Bloom, Jonathan, and Sheila Blair. Islamic Arts. London: Phaidon Press, 1997.

The Nature of Islamic Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Archnet, a resource focused on architecture, urbanism, environmental and landscape design, visual culture, and conservation issues related to the Muslim world

Islamic Art reading list from the Victoria and Albert Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Five Pillars of Islam

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Almost as soon as the Arab armies of Islam conquered new lands, they began erecting mosques and palaces, as well as commissioning other works of art as expressions of their faith and culture. Connected to this, many aspects of religious practice in Islam also emerged and were codified. The religious practice of Islam, which literally means to submit to God, is based on tenets that are known as the Five Pillars (arkan), to which all members of the Islamic community (Umma) should adhere.

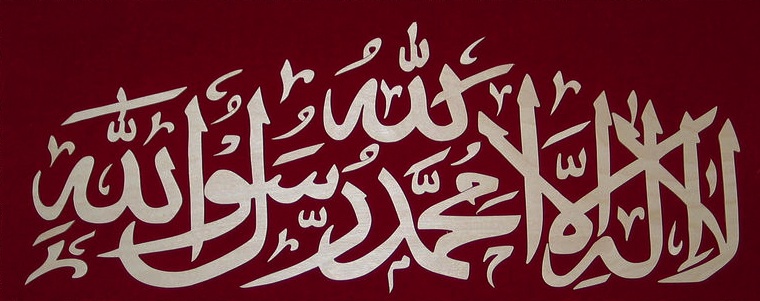

1. The profession of faith (the shahada)

The profession of Faith (the shahada) is the most fundamental expression of Islamic beliefs. It simply states that “There is no God but God and Muhammad is his prophet.” It underscores the monotheistic nature of Islam. It is an extremely popular phrase in Arabic calligraphy and appears in numerous manuscripts and religious buildings.

2. Daily prayers (salat)

Muslims are expected to pray five times a day. This does not mean that they need to attend a mosque to pray; rather, the salat, or the daily prayer, should be recited five times a day. Muslims can pray anywhere; however, they are meant to pray towards Mecca. The faithful are meant to pray by bowing several times while standing and then kneel and touch the ground or prayer mat with their foreheads, as a symbol of their reverence and submission to Allah. On Friday, many Muslims attend the mosque near mid-day to pray and to listen to a sermon (khutba).

3. Alms-giving (zakat)

The giving of alms is the third pillar. Although not defined in the Qu’ran, Muslims believe that they are meant to share their wealth with those less-fortunate in their community of believers.

4. Fasting during Ramadan (saum)

During the holy month of Ramadan (the ninth month in the Islamic calendar), Muslims are expected to fast from dawn to dusk. While there are exceptions made for the sick, elderly, and pregnant, all are expected to refrain from eating and drinking during day-light hours.

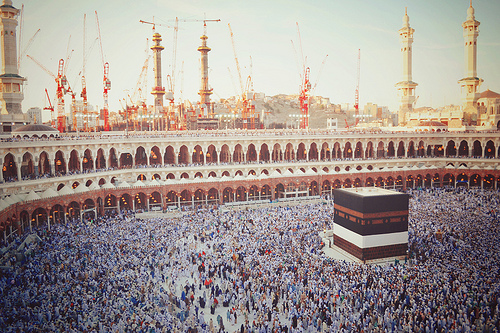

5. Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca

All Muslims who are able, are required to make the pilgrimage to Mecca and the surrounding holy sites at least once in their lives. Pilgrimage focuses on visiting the Kaaba and walking around it seven times. Pilgrimage occurs in the twelfth month of the Islamic Calendar.

Additional resources:

Hajj Stories from the Asian Art Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Hajj

Mecca and the Ka’ba

One of the five pillars of Islam central to Muslim belief, Hajj is the pilgrimage to Mecca that every Muslim must make at least once in their lifetime if they are able; it is the most spiritual event that a Muslim experiences, observing rituals in the most sacred places in the Islamic world. Mecca is the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad. The sanctuary there with the Ka‘ba is the holiest site in Islam. As such, it is a deeply spiritual destination for Muslims all over the world; it is the heart of Islam.

At the heart of the sanctuary at Mecca lies the Ka’ba, the cube-shaped building that Muslims believe was built by Abraham and his son Ishmael. It was in Mecca that the Prophet Muhammad received the first revelations in the early 7th century. Therefore the city has long been viewed as a spiritual centre and the heart of Islam. The rituals involved with Hajj have remained unchanged since its beginning, and it continues to be a powerful religious undertaking which draws Muslims together from all over the world, irrespective of nationality or sect.

Even before Islam, Mecca was an important site of pilgrimage for the Arab tribes of north and central Arabia. Although they believed in many deities, they came once a year to worship Allah at Mecca. During this sacred month, violence was forbidden within Mecca, allowing trade to flourish. As a result, Mecca became an important commercial centre. The revelation of Islam to the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632) restored the ancient religion of the One God to the Arab people and transformed Mecca into the holiest city in the Islamic world.

The rituals

Hajj involves a series of rituals that take place in and around Mecca over a period of five to six days. The first of these is tawaf in which pilgrims walk around the Ka‘ba seven times in an anti-clockwise direction. Muslims believe that the rituals of Hajj have their origin in the time of the prophet Ibrahim (Abraham). Muhammad led the Hajj himself in 632, the year of his death. The Hajj now attracts about three million pilgrims every year from across the world.

The journey

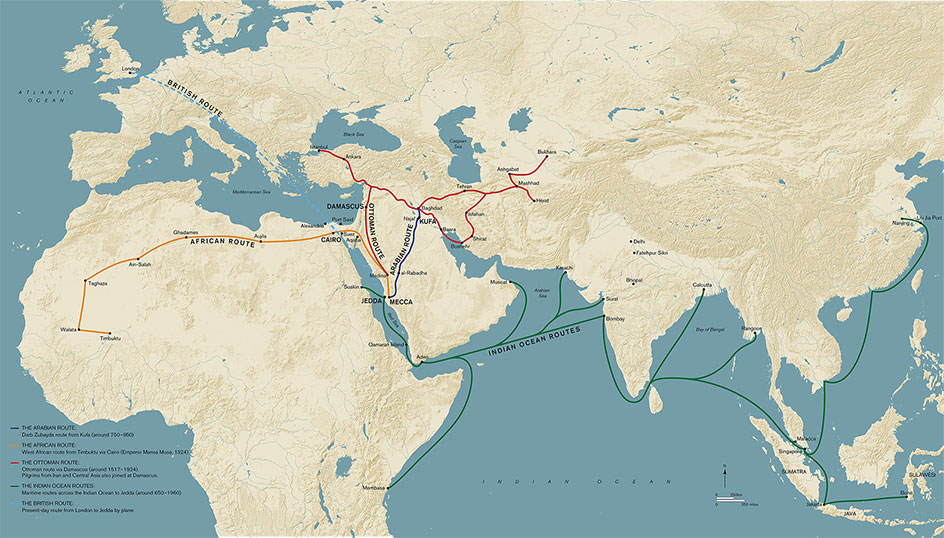

From the furthest reaches of the Islamic world, pilgrims have made the spiritual journey that is the ambition of a lifetime. As Hajj needs to be performed at a designated time, historically pilgrims moved together in convoys. In the past the journey could be extremely dangerous. Pilgrims often fell ill or were robbed on the way and became destitute. However, pilgrims do not fear dying on Hajj. It is believed that those who die on Hajj will go to heaven with their sins erased. Today, pilgrims can get on an airplane to reach Saudi Arabia, making the journey in contrast with the past quick and less arduous.

The Qur’an states that Hajj should take place “in the specified months,” and these are the last three months of the Muslim calendar, known as Miqat Zamani (fixed times). Although the main acts of the Hajj take place in five days during the twelfth month, a pilgrim can start going into consecration (ihram) for Hajj earlier, from the beginning of the tenth month (Shawwal). The Muslim calendar is lunar, which means that the Hajj takes place progressively across all four seasons over time rather than in the full heat of summer every year. On foot, by camel, boat, train or airplane, going on Hajj is a spiritual endeavor that begins at home and culminates in Mecca; in going, arriving, and returning, the pilgrim is mindful of the magnitude of the journey and the reward in this world and the hereafter.

When pilgrims undertake the Hajj journey, they follow in the footsteps of millions before them. Nowadays hundreds of thousands of believers from over 70 nations arrive in Mecca in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by road, sea and air every year, completing a journey faster and in some ways less arduous than it often was in the past. Those traveling overland by camel and on foot congregated at three central points: Kufa (Iraq), Damascus (Syria) and Cairo (Egypt). Pilgrims coming by sea would enter Arabia at the port of Jedda.

© Trustees of the British Museum

The Kaaba

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Prayer and pilgrimage

Pilgrimage to a holy site is a core principle of almost all faiths. The Kaaba, meaning cube in Arabic, is a square building, elegantly draped in a silk and cotton veil. Located in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, it is the holiest shrine in Islam.

In Islam, Muslims pray five times a day and after 624 C.E., these prayers were directed towards Mecca and the Kaaba rather than Jerusalem; this direction (or qibla in Arabic), is marked in all mosques and enables the faithful to know in what direction they should pray. The Qur‘an established the direction of prayer.

All Muslims aspire to undertake the hajj, or the annual pilgrimage, to the Kaaba once in their life if they are able. Prayer five times a day and the hajj are two of the five pillars of Islam, the most fundamental principles of the faith.

Upon arriving in Mecca, pilgrims gather in the courtyard of the Masjid al-Haram around the Kaaba. They then circumambulate (tawaf in Arabic) or walk around the Kaaba, during which they hope to kiss and touch the Black Stone (al-Hajar al-Aswad), embedded in the eastern corner of the Kaaba.

The history and form of the Kaaba

The Kaaba was a sanctuary in pre-Islamic times. Muslims believe that Abraham (known as Ibrahim in the Islamic tradition), and his son, Ismail, constructed the Kaaba. Tradition holds that it was originally a simple unroofed rectangular structure. The Quraysh tribe, who ruled Mecca, rebuilt the pre-Islamic Kaaba in c. 608 C.E. with alternating courses of masonry and wood. A door was raised above ground level to protect the shrine from intruders and flood waters.

Muhammad was driven out of Mecca in 620 C.E. to Yathrib, which is now known as Medina. Upon his return to Mecca in 629/30 C.E., the shrine became the focal point for Muslim worship and pilgrimage. The pre-Islamic Kaaba housed the Black Stone and statues of pagan gods. Muhammad reportedly cleansed the Kaaba of idols upon his victorious return to Mecca, returning the shrine to the monotheism of Ibrahim. The Black Stone is believed to have been given to Ibrahim by the angel Gabriel and is revered by Muslims. Muhammad made a final pilgrimage in 632 C.E., the year of his death, and thereby established the rites of pilgrimage.

Modifications

The Kaaba has been modified extensively throughout its history. The area around the Kaaba was expanded in order to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims by the second caliph, ‘Umar (ruled 634-44). The Caliph ‘Uthman (ruled 644-56) built the colonnades around the open plaza where the Kaaba stands and incorporated other important monuments into the sanctuary.

During the civil war between the caliph Abd al-Malik and Ibn Zubayr who controlled Mecca, the Kaaba was set on fire in 683 C.E. Reportedly, the Black Stone broke into three pieces and Ibn Zubayr reassembled it with silver. He rebuilt the Kaaba in wood and stone, following Ibrahim’s original dimensions and also paved the space around the Kaaba. After regaining control of Mecca, Abd al-Malik restored the part of the building that Muhammad is thought to have designed. None of these renovations can be confirmed through study of the building or archaeological evidence; these changes are only outlined in later literary sources.

Reportedly under the Umayyad caliph al-Walid (ruled 705-15), the mosque that encloses the Kaaba was decorated with mosaics like those of the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus. By the seventh century, the Kaaba was covered with kiswa, a black cloth that is replaced annually during the hajj.

Under the early Abbasid Caliphs (750-1250), the mosque around the Kaaba was expanded and modified several times. According to travel writers, such as the Ibn Jubayr, who saw the Kaaba in 1183, it retained the eighth century Abbasid form for several centuries. From 1269-1517, the Mamluks of Egypt controlled the Hijaz, the highlands in western Arabia where Mecca is located. Sultan Qaitbay (ruled 1468-96) built a madrasa (a religious school) against one side of the mosque. Under the Ottoman sultans, Süleyman I (ruled 1520-1566) and Selim II (ruled 1566-74), the complex was heavily renovated. In 1631, the Kaaba and the surrounding mosque were entirely rebuilt after floods had demolished them in the previous year. This mosque, which is what exists today, is composed of a large open space with colonnades on four sides and with seven minarets, the largest number of any mosque in the world. At the center of this large plaza sits the Kaaba, as well as many other holy buildings and monuments.

The last major modifications were carried out in the 1950s by the government of Saudi Arabia to accommodate the increasingly large number of pilgrims who come on the hajj. Today the mosque covers almost forty acres.

The Kaaba today

Today, the Kaaba is a cubical structure, unlike almost any other religious structure. It is fifteen meters tall and ten and a half meters on each side; its corners roughly align with the cardinal directions. The door of the Kaaba is now made of solid gold; it was added in 1982. The kiswa, a large cloth that covers the Kaaba, which used to be sent from Egypt with the hajj caravan, today is made in Saudi Arabia. Until the advent of modern transportation, all pilgrims undertook the often dangerous hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca in a large caravan across the desert, leaving from Damascus, Cairo, or other major cities in Arabia, Yemen or Iraq.

The numerous changes to the Kaaba and its associated mosque serve as good reminder of how often buildings, even sacred ones, were renovated and remodeled either due to damage or to the changing needs of the community.

Only Muslims may visit the holy cities of Mecca and Medina today.

Additional resources:

Hajj Stories from the Asian Art Museum

Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, “Mecca” in The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and Architecture, Oxford University Press, 2009.

K. A. C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, Oxford University Press, 1932/revised and enlarged 1969.

Stories of the modern pilgrimage

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Every year, 25,000 British Muslims make the pilgrimage to Mecca. As part of the exhibition, Hajj: journey to the heart of Islam, the British Museum asked what this journey is like. Video © Trustees of the British Museum.

Additional resources:

More Hajj stories from the Asian Art Museum

The complex geometry of Islamic design

by TED-ED

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video from TED-Ed. Speaker: Eric Broug.

Introduction to mosque architecture

From Indonesia to the United Kingdom, the mosque in its many forms is the quintessential Islamic building. The mosque, masjid in Arabic, is the Muslim gathering place for prayer. Masjid simply means “place of prostration.” Though most of the five daily prayers prescribed in Islam can take place anywhere, all men are required to gather together at the mosque for the Friday noon prayer.

Mosques are also used throughout the week for prayer, study, or simply as a place for rest and reflection. The main mosque of a city, used for the Friday communal prayer, is called a jami masjid, literally meaning “Friday mosque,” but it is also sometimes called a congregational mosque in English. The style, layout, and decoration of a mosque can tell us a lot about Islam in general, but also about the period and region in which the mosque was constructed.

The home of the Prophet Muhammad is considered the first mosque. His house, in Medina in modern-day Saudi Arabia, was a typical 7th-century Arabian style house, with a large courtyard surrounded by long rooms supported by columns. This style of mosque came to be known as a hypostyle mosque, meaning “many columns.” Most mosques built in Arab lands utilized this style for centuries.

Common features

The architecture of a mosque is shaped most strongly by the regional traditions of the time and place where it was built. As a result, style, layout, and decoration can vary greatly. Nevertheless, because of the common function of the mosque as a place of congregational prayer, certain architectural features appear in mosques all over the world.

Sahn (courtyard)

The most fundamental necessity of congregational mosque architecture is that it be able to hold the entire male population of a city or town (women are welcome to attend Friday prayers, but not required to do so). To that end congregational mosques must have a large prayer hall. In many mosques this is adjoined to an open courtyard, called a sahn. Within the courtyard one often finds a fountain, its waters both a welcome respite in hot lands, and important for the ablutions (ritual cleansing) done before prayer.

Mihrab (niche)

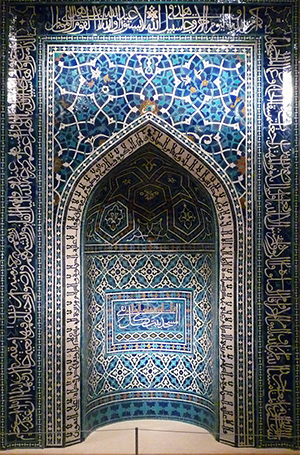

Another essential element of a mosque’s architecture is a mihrab—a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of Mecca, towards which all Muslims pray. Mecca is the city in which the Prophet Muhammad was born, and the home of the most important Islamic site, the Kaaba. The direction of Mecca is called the qibla, and so the wall in which the mihrab is set is called the qibla wall. No matter where a mosque is, its mihrab indicates the direction of Mecca (or as near that direction as science and geography were able to place it). Therefore, a mihrab in India will be to the west, while a one in Egypt will be to the east. A mihrab is usually a relatively shallow niche, as in the example from Egypt, above. In the example from Spain, shown right, the mihrab’s niche takes the form of a small room, this is more rare.

Minaret (tower)

One of the most visible aspects of mosque architecture is the minaret, a tower adjacent or attached to a mosque, from which the call to prayer is announced.

Minarets take many different forms—from the famous spiral minaret of Samarra, to the tall, pencil minarets of Ottoman Turkey. Not solely functional in nature, the minaret serves as a powerful visual reminder of the presence of Islam.

Qubba (dome)

Most mosques also feature one or more domes, called qubba in Arabic. While not a ritual requirement like the mihrab, a dome does possess significance within the mosque—as a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven. The interior decoration of a dome often emphasizes this symbolism, using intricate geometric, stellate, or vegetal motifs to create breathtaking patterns meant to awe and inspire. Some mosque types incorporate multiple domes into their architecture (as in the Ottoman Süleymaniye Mosque pictured at the top of the page), while others only feature one. In mosques with only a single dome, it is invariably found surmounting the qibla wall, the holiest section of the mosque. The Great Mosque of Kairouan, in Tunisia (not pictured) has three domes: one atop the minaret, one above the entrance to the prayer hall, and one above the qibla wall.

Because it is the directional focus of prayer, the qibla wall, with its mihrab and minbar, is often the most ornately decorated area of a mosque. The rich decoration of the qibla wall is apparent in this image of the mihrab and minbar of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan in Cairo, Egypt (see image higher on the page).

Furnishings

There are other decorative elements common to most mosques. For instance, a large calligraphic frieze or a cartouche with a prominent inscription often appears above the mihrab. In most cases the calligraphic inscriptions are quotations from the Qur’an, and often include the date of the building’s dedication and the name of the patron. Another important feature of mosque decoration are hanging lamps, also visible in the photograph of the Sultan Hasan mosque. Light is an essential feature for mosques, since the first and last daily prayers occur before the sun rises and after the sun sets. Before electricity, mosques were illuminated with oil lamps. Hundreds of such lamps hung inside a mosque would create a glittering spectacle, with soft light emanating from each, highlighting the calligraphy and other decorations on the lamps’ surfaces. Although not a permanent part of a mosque building, lamps, along with other furnishings like carpets, formed a significant—though ephemeral—aspect of mosque architecture.

Mosque patronage

Most historical mosques are not stand-alone buildings. Many incorporated charitable institutions like soup kitchens, hospitals, and schools. Some mosque patrons also chose to include their own mausoleum as part of their mosque complex. The endowment of charitable institutions is an important aspect of Islamic culture, due in part to the third pillar of Islam, which calls for Muslims to donate a portion of their income to the poor.

The commissioning of a mosque would be seen as a pious act on the part of a ruler or other wealthy patron, and the names of patrons are usually included in the calligraphic decoration of mosques. Such inscriptions also often praise the piety and generosity of the patron. For instance, the mihrab now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, bears the inscription:

And he [the Prophet], blessings and peace be upon him, said: “Whoever builds a mosque for God, even the size of a sand-grouse nest, based on piety, [God will build for him a palace in Paradise].”

The patronage of mosques was not only a charitable act therefore, but also, like architectural patronage in all cultures, an opportunity for self-promotion. The social services attached the mosques of the Ottoman sultans are some of the most extensive of their type. In Ottoman Turkey the complex surrounding a mosque is called a kulliye. The kulliye of the Mosque of Sultan Suleyman, in Istanbul, is a fine example of this phenomenon, comprising a soup kitchen, a hospital, several schools, public baths, and a caravanserai (similar to a hostel for travelers). The complex also includes two mausoleums for Sultan Suleyman and his family members.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Common types of mosque architecture

Since the 7th century, mosques have been built around the globe. While there are many different types of mosque architecture, three basic forms can be defined.

I. The hypostyle mosque

It makes sense that the first place of worship for muslims, the house of the Prophet Muhammad, inspired the earliest type of mosque – the hypostyle mosque. This type spread widely throughout Islamic lands.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, is an archetypal example of the hypostyle mosque. The mosque was built in the ninth century by Ziyadat Allah, the third ruler of the Aghlabid dynasty, an offshoot of the Abbasid Empire. It is a large, rectangular stone mosque with a hypostyle (supported by columns) hall and a large inner sahn (courtyard). The three-tiered minaret is in a style known as the Syrian bell-tower, and may have originally been based on the form of ancient Roman lighthouses. The interior of the mosque features the forest of columns that has come to define the hypostyle type.

The mosque was built on a former Byzantine site, and the architects repurposed older materials, such as the columns—a decision that was both practical and a powerful assertion of the Islamic conquest of Byzantine lands. Many early mosques like this one made use of older architectural materials (called spolia), in a similarly symbolic way.

On right hand side of mosque’s mihrab is the maqsura, a special area reserved for the ruler found in some, but not all, mosques. This mosque’s maqsura is the earliest extant example, and its minbar (pulpit) is the earliest dated minbar known to scholars. Both are carved from teak wood that was imported from Southeast Asia. This prized wood was shipped from Thailand to Baghdad where it was carved, then carried on camel back from Iraq to Tunisia, in a remarkable display of medieval global commerce.

The hypostyle plan was used widely in Islamic lands prior to the introduction of the four-iwan plan in the twelfth century (see next section). The hypostyle plan’s characteristic forest of columns was used in different mosques to great effect. One of the most famous examples is the Great Mosque of Cordoba, which uses bi-color, two-tier arches that emphasize the almost dizzying optical effect of the hypostyle hall.

II. The four-iwan mosque

Just as the hypostyle hall defined much of mosque architecture of the early Islamic period; the 11th century shows the emergence of new form: the four-iwan mosque. An iwan is a vaulted space that opens on one side to a courtyard. The iwan developed in pre-Islamic Iran where it was used in monumental and imperial architecture. Strongly associated with Persian architecture, the iwan continued to be used in monumental architecture in the Islamic era.

In 11th century Iran, hypostyle mosques started to be converted into four-iwan mosques, which, as the name indicates, incorporate four iwans in their architectural plan.

The Great Mosque of Isfahan reflects this broader development. The mosque began its life as a hypostyle mosque, but was modified by the Seljuqs of Iran after their conquest of the city of Isfahan in the 11th century.

Like a hypostyle mosque, the layout is arranged around a large open courtyard. However, in the four-iwan mosque, each wall of the courtyard is punctuated with a monumental vaulted hall, the iwan. This mosque type, which became widespread in the 12th century, has maintained its popularity to the present.

In this type of mosque the qibla iwan, which faces Mecca, is often the largest and most ornately decorated, as at Isfahan’s Great Mosque. Here, the mosque’s two minarets also flank the lavish qibla iwan. The Safavid rulers refurbished these walls with new tiles in the 16th century.

Though it originated in Iran, the four-iwan plan would become the new plan for mosques all over the Islamic word, used widely from India to Cairo and replacing the hypostyle mosque in many places.

III. The centrally-planned mosque

While the four-iwan plan was used for mosques across the Islamic world, the Ottoman Empire was one of the few places in the central Islamic lands where the four-iwan mosque plan did not dominate. The Ottoman Empire was founded in 1299. However, it did not become a major force until the 15th century, when Mehmed II conquered Constantinople, the capital of the late Roman (Byzantine) Empire since the 4th century. Renamed Istanbul, the city straddles the European and Asian continents, and, having been a Christian capital for over a thousand years, had a wholly different cultural and architectural heritage than Iran. The Ottoman architects were strongly influenced by Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the greatest of all Byzantine churches and one that features a monumental central dome high over its large nave.

Many Ottoman mosques in the late 15th and early 16th centuries referenced Hagia Sophia’s dome; however, it was not until the masterful work of Mimar Sinan, the greatest Ottoman, if not Islamic, architect, that the domes of Ottoman mosques competed with and arguably surpassed that of Hagia Sophia. Sinan experimented with the central plan in a series of mosques in Istanbul, achieving what he considered his masterpiece in the Mosque of Selim II, in Edirne, Turkey. Built for Selim II, son of Suleyman during the golden age of the Ottoman Empire, it is considered the greatest masterpiece of Ottoman architecture. It represents a culmination of years of experimentation with the centrally-planned Ottoman mosque.

Sinan himself boasted that his dome was higher and wider than that of the Hagia Sophia, highlighting the sense of competition with the earlier Byzantine building. In the Selim Mosque, Sinan distilled previous ideas about the central plan into a simple and perfect design. The interior octagonal space was made more spacious by 8 massive piers that pushed back into the walls, and a rhythmic harmony was created through apertures of small and large arches framed by joggled voussoirs, filling the large space with light and color.

Mosque architecture around the world

The three mosque types described above are the most common, and most historically significant, in the Islamic world. Despite their common features, such as mihrabs and minarets, one can see that diverse regional styles account for dramatic differences in the colors, materials, and the overall decoration of mosques. The bright blue and white tiled mihrabs of fourteenth-century Iran are a world apart from the muted colors and stone inlay of an Egyptian mihrab of the same century.

Even more regional differences appear when one looks beyond the central Islamic lands to the architecture of Muslims living in places like China, Africa, and Indonesia, where local materials and regional traditions, sometimes with little influence from the architectural heritage of the central Islamic lands, influenced mosque architecture.

The minaret at Kudus, Indonesia, for instance, reflects the influence of Hindu architecture. The Djingarey Berre Mosque of Timbuktu, in Mali, similarly responds to the pre-Islamic traditions of its own region, utilizing a unique West African style and using earth as the primary building material.

An early mosque in Xian, China, uses a very clearly Chinese style of architecture (below, left), but also incorporates more typical Islamic elements, like squinches and a distinctly Islamic-style arched mihrab (below, right).

Contemporary mosque architecture

Contemporary mosque architecture often represents a remarkable blending of styles, drawing from diverse architectural traditions to create something recognizably “Islamic,” that fulfills all the architectural requirements of a communal mosque and is contemporary in style. In Pakistan, the King Faisal Mosque, 1986 blends contemporary architecture with visual references to traditional forms. The building is strikingly modern, yet plays with the form of the tent structures of Bedouin nomads. This large mosque also incorporates Ottoman-influenced pencil-thin minarets into its modern design.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: