Afterword

- Page ID

- 70148

University at Albany

I am honored to have been asked to write the afterword for this important volume. We are at a time when the world of information possibilities has exploded—not just the resources available to us, which are overwhelming and often daunting, but also the roles each one of us can play in creating, collaborating, sharing, and disseminating information. As academics, these roles tend to come naturally. Our facility in engaging with information in our own fields coincides with our abilities to create and share other forms of information, and to use less traditional modes of dissemination. We may write letters to the editors of periodicals. We may contribute reflective posts on social media, be it tweets or via professional or personal-interest blogs, or contribute reviews—product, hotel, or restaurant—to help others. We understand the need for varying formats of information creation and modes of information dissemination to suit specific purposes and to reach varying audiences.

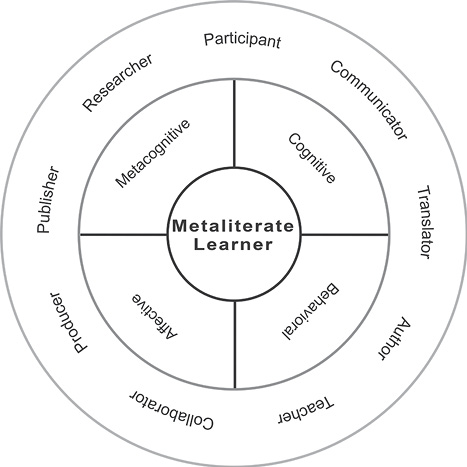

The variety of information-related roles is outlined in the outer ring of Figure A.1.

Figure A.1. The Metaliterate Learner (Mackey & Jacobson, 2014).

These roles are now open to almost everyone, but many do not see themselves as information producers and distributors nor as teachers or translators of information. Even if our students are actually engaging in these activities, they may not recognize the full potential of what they are able to do.

When students post online, for example, they don’t see this as a reflection, often a lasting one, of themselves. Rather than understanding that they are shaping an online persona, they might see their utterances as disconnected and effect-neutral. And for those who do not feel comfortable participating, it leads to a loss of unique voices and perspectives in online communities. Educators have the opportunity, indeed duty, to introduce these roles to our students, and information literacy (IL) is a powerful player in these conversations.

As this collaborative collection epitomizes, IL is a shared responsibility. No longer do we consider IL to be a simple set of discrete skills connected with finding and evaluating information. Two of the themes discussed in this volume, metaliteracy and the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (Framework for IL) (which was itself influenced by metaliteracy) are extending beyond and opening new vistas in the field. While the ideas encompassed by both of these constructs are not entirely new, each provides its own cohesive lens that opens up exciting opportunities for thinking about and teaching IL. The overlap between metaliteracy and the Framework for IL allows them to support and enhance each other.

Both metaliteracy and the Framework for IL address multiple domains (metacognitive, cognitive, behavioral, and affective), providing a rich scope for learning activities. As reflected in the chapters in this collection, educators are identifying potent opportunities to empower learners, and in the process, we also learn from our students. The fertile ground provided by this environment is reflected in the chapters you have just read. As you did so, you probably imagined how you might alter this piece, and tweak that, and add a dash of this, and end up with something very exciting to try out on your own campus.

As educators, we may be animated by the possibilities, but crucially, how do students respond? Section IV’s chapters describe collaborative pedagogical techniques used by their author teams. The frame Scholarship as Conversation is highlighted in the first chapter in Section III, Miriam Laskin’s and Cynthia Haller’s “Up the Mountain without a Trail: Helping Students Use Source Networks to Find Their Way.” In my own classroom I have seen that concepts critical to IL, such as this one, engage students once they understand how they relate to their academic and non-academic needs. In one of my upper-level undergraduate courses, teams of students wrestled with Scholarship as Conversation individually and through discussion, including reflecting on associated dispositions. In order to assess their grasp of the core ideas, a team-based culminating project asked them to develop a lesson plan to introduce lower-level undergraduates to this frame. The lesson plan needed to include an activity and a final project for these hypothetical students to complete. I was amazed with the teams’ responses to this challenge, which included a 30-minute deadline. Their work indicated that they had grasped the core ideas contained within the frame. In addition, the students saw themselves in new roles: those of information producer and teacher. These outcomes highlight the fundamental difference between teaching students basic skills and introducing them to core concepts in the field. But teaching on this higher level requires more than just the one class period often allotted to a librarian. Collaboration in this endeavor is crucial.

The discussion about who is responsible for IL instruction is long-standing and ongoing. When the topic of the instruction was library research skills, it was clear that librarians played the key role. But IL goes far beyond library research, as is evident in the chapters in this volume. Its scope is expansive; the need permeates life, both on campus and off, as well as on and off the job. With the conceptions of IL as a metaliteracy, and the core concepts espoused by the Framework for IL, it becomes clear that teaching and modeling information-literate competencies is a challenge that needs to be undertaken by all educators.

I applaud the vision expressed in the Introduction: “we hoped that a collection that bridged the disciplinary divide would advance the notion of shared responsibility and accountability for IL.” Conversations such as the ones that this book will initiate are vital in making IL a strong component of higher education. Give and take will be important: librarians and disciplinary faculty members will each have contributions to share, and things to learn. The terms and framing may differ, but there will be much common ground. As Caroline Sinkinson says in her chapter with Rolf Norgaard, citing Barabara Fister: we “need to trust one another and have a sense of shared ownership.” Norgaard and Sinkinson are discussing collaborations between librarians and Rhetoric and Writing Instructors, but Fister’s advice is pertinent for all such initiatives. The issue of language and ownership are addressed in Susan Brown and Janice R. Walker’s “Information Literacy Preparation of Pre-Service and Graduate Educators” (chapter 13).

The material in this book has engaged you with the new ideas, new theories, and new terminology, introduced through metaliteracy and the Framework for IL, and also through the collaborations described in some of the chapters. This willingness to grapple with the new is critical in moving IL forward, and I call upon you to serve as advocates for these new theories and ideas. Your adaptation of these concepts will in turn motivate and inspire others both in your own field, as well as outside it. Please share your enthusiasms, your insights, and your experiences.

And please do so with your students as well. Provide the scaffolding they might need, but let them struggle with the nuances of the ideas and understandings that lead to the concepts and the resulting competencies.

I was struck by something that Barbara Fister said during her keynote presentation for librarians at the 2015 Librarian’s Information Literacy Annual Conference (LILAC) in Newcastle, UK. She talked about the liminal space that precedes crossing the threshold for each concept in the Framework for IL, and the worry that librarians, in desiring to be helpful, will attempt to move learners over the threshold without their having a chance to really wrestle with the understandings they need to master. Let them flounder a bit—we all did when we first encountered these key concepts. The nature of threshold concepts is that it is hard to remember what or how we thought before we crossed the threshold. This is what I took away from one of her points during her talk. In looking for the source, to make sure my memory was accurate, I found her exact wording:

What really caught my imagination was their focus on identifying those moments when students make a significant breakthrough in their understanding, a breakthrough that changes the relationship they have with information. If we know what those moments are, we can think about how our teaching practices can either help students work toward those moments of insight or perhaps inadvertently hinder them by describing a simple step by step process that defuses troublesomeness to make it more manageable (Fister, 2015).

Fister was referring to a 2013 Library Orientation Exchange (LOEX) presentation by Lori Townsend and Amy Hofer (see http://www.loexconference.org/2013/s....html#townsend). Not coincidentally, Townsend was a member of the ACRL task force that developed the new Framework for IL.

I highly encourage you to read the text of Fister’s talk, “The Liminal Library,” which she has generously provided online (Fister, 2015) She touches on many of the themes included in this collection, including students, collaboration, language, the changing nature and definition of IL including metaliteracy, the movement from the IL Standards to the Framework for IL, and more.

This is an exciting time to explore and to teach information literacy/metaliteracy. The authors whose work is collected in this volume have conveyed that energy. It is now your turn to add to the increasing dynamism in the field. And wouldn’t you like to share that excitement with a partner from another discipline?

References

Fister, B. (2015). The liminal library: Making our libraries sites of transformative learning. Retrieved September 3, 2015, from http://barbarafister.com/LiminalLibrary.pdf

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2014). Metaliteracy: reinventing information literacy to empower learners. Chicago: Neal-Schuman.