19: Impacting Information Literacy through Alignment, Resources, and Assessment

- Page ID

- 70144

Chapter 19. Impacting Information Literacy through Alignment, Resources, and Assessment

Beth Bensen, Denise Woetzel, Hong Wu, and Ghazala Hashmi

J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College

Introduction

In the late 1990s, the Governor of Virginia charged a Blue Ribbon Commission on Higher Education to make recommendations for the future of Virginia’s public four-year and two-year post-secondary institutions, with the goals of improving quality, affordability, and accountability. In its final report released in 2000, the Commission recommended that the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) implement a Quality Assurance Plan that would define and assess the core competencies that “every graduate of every Virginia college or university regardless of major, can be expected to know and be able to do” and that the core competencies should include “at least written communication, mathematical analysis, scientific literacy, critical thinking, oral communication, and technology” (Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission, 2000, p. 51).

In response, the Chancellor of the Virginia Community College System (VCCS) formed the VCCS Task Force on Assessing Core Competencies in 2002. The task force decided to define technology in terms of information literacy (IL) “because of the long-standing emphasis at the colleges on assessing computer competencies” (Virginia Community College System, 2002, p. 6). The task force adopted the Association of College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (IL Standards) (2000) and defined IL as “a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000). This chapter’s primary focus is on the IL Standards and does not address the ACRL (2015) Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (Framework for IL). The Framework for IL was filed in its final form in February 2015. In spring 2015 Reynolds librarians began review and discussion of developing learning outcomes tied to the six IL frames.

However, in the mid-1990s James Madison University (JMU) began development of a Web-based platform for IL instruction titled Information-Seeking Skills Test (ISST) (Cameron, Wise & Lottridge, 2007, p. 230). Also in the 1990s, JMU began development of another Web-based IL application, Go for the Gold (Cameron & Evans, n.d.). Both platforms were built on ACRL IL Standards. Go for the Gold is composed of eight self-instruction modules with online exercises that teach students to identify and locate library services and collection, employ efficient search techniques with a variety of information sources, evaluate and cite information sources, and apply appropriate ethical guidelines to the use of the information. ISST is a Web-based test that is composed of 54 questions to assess student information competencies as instructed in Go for the Gold. All first year students at JMU were required to take both Go for the Gold and ISST as part of the general education requirements (James Madison University Libraries, n.d., para. 1). JMU used the assessment results in the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools accreditation review and to meet system-wide goals set by SCHEV (Cameron, Wise & Lottridge, 2007, p. 231).

Because the information competencies assessed by JMU’s ISST match that of ACRL IL Standards, VCCS licensed ISST to comply with SCHEV’s mandate to assess IL competencies in 2003. VCCS established a score of 37 (out of 54) as indicating overall competency and 42 as highly competent. Each of the 23 VCCS community colleges developed their own testing plan. Nine colleges chose to test graduates, six chose students in ENG 112, and eight chose one or another of their courses that would involve students from varied programs. System wide, a total of 3,678 students completed ISST. Among the test takers, 53.18% of VCCS-wide students and only 26.42% Reynolds students met or exceeded the required standard (a score of 37 out of 54). Although VCCS developed a tutorial titled Connect for Success based on Go for the Gold to prepare students for the test, most of Reynolds instructors and students were not aware of the tutorial. Institutional librarians were not involved in the test planning and implementation and there was no collaboration or communication between faculty and librarians. These less-than-desirable results confirmed the fact that the statewide charge for the IL competency assessment was not balanced by a corresponding institutional mandate on how to develop, provide, and assess IL competencies within the standard general education curriculum.

Prior to 2003, only a handful of Reynolds faculty requested library instruction; these requests could not be made electronically and were limited to one 50-75 minute class period, with little room for student engagement. With no uniform instructional guidelines available to them, librarians provided instruction without guarantee of consistency among themselves. Additionally, with no assessment activities in place, the efficacy of instruction could not be appropriately evaluated. Reynolds students’ low scores on the ISST assessment coupled with inconsistency in IL instructional methods signaled the urgent need to adopt a number of remedying measures. The measures included the following:

- Development of library instruction packages based upon ACRL’s IL Standards.

- Dissemination of an online library instruction request form that included a list of packages and skill sets, allowing faculty to tailor instruction to their research assignments and also serving as a guideline for consistency among librarians.

- Training of librarians on the delivery of effective library instruction

- Publication of a new marketing plan pertaining to the IL program: librarians presented at campus-wide meetings, emailed information to faculty, and used social networking media such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs.

- Implementation of assessment activities, such as multiple-choice quizzes within Blackboard and various student worksheets, enabling librarians and faculty to better evaluate student learning

- Creation of research guides tailored to specific assignments, courses and subjects first through PBwiki in 2005 and then through Springshare’s LibGuides in 2009. Librarians used these guides during instruction sessions and linked them to individual Blackboard course sites.

- Development of a variety of open session workshops, enabling students to register and attend sessions on their own time.

- Creation of an online tutorial in the form of seven modules based upon ACRL’s IL Standards and titled Research at Reynolds Library (2015). This tutorial guides students through a complete research process from exploring topics and finding resources to evaluating and citing resources. Faculty choose to integrate all seven modules or select specific ones for their courses. Each module is accompanied by ten self-assessment questions, with the exception of Module Five, which includes seven questions.

- Dedication of computer labs at two of the college’s three libraries in which students receive hands-on experience during IL sessions.

Although these remedies continue to evolve, most of the steps listed above began to take effect in 2005 and remain in place. However, despite these many efforts, Reynolds librarians still faced the same essential concerns: the absence of a college mandate for the effective delivery of IL skills, the mapping of these skills within the general education curriculum, and the assessment of student learning. Complicating matters was the lack of coordinated collaboration between librarians and faculty to align instructional resources with essential course outcomes within specific areas of the general education curriculum.

Literature Review: Assessment and Collaboration Practices

Regional accrediting agency mandates to assess core IL skills (Saunders, 2007, pp. 317-318; Saunders, 2008, p. 305), as well as academic institutions’ continuing focus on assessment, presents libraries with an opportunity to play a greater role in campus-wide assessment activities and contribute to student success (Lewis, 2010, p. 74; Saunders, 2011, p. 21). Librarians that connect their assessment plans to the mission and goals of their institution will be more effective in presenting and communicating their achievements in the area of IL (White & Blankenship, 2007, p. 108). According to Patricia Davitt Maughan (2001), several critical reasons for assessing students’ IL skills include developing a core set of learning outcomes as a foundation for the IL program, assessing the effectiveness of instructional methods, measuring student success within the program, and communicating data results to faculty (p. 74).

One way to address outcomes is to focus on existing outcomes as developed by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (WPA). The WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (WPA OS), first published in 2000 and amended in 2008, includes five sections: Rhetorical Knowledge; Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing; Processes; Knowledge of Conventions; and Composing in Electronic Environments. The most recent version of the WPA OS was published in 2014; however, the English Department relevant to this study developed Reynolds ENG 112 learning outcomes based on the amended 2008 version. This discussion will focus on the amended 2008 version with the knowledge that a more recent version exists. For the purposes of this discussion, the two sections on which we will focus are Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing (CTRW) and Composing in Electronic Environments (CEE). Both of these sections address IL skills, with CTRW suggesting that students may develop the following skills:

- Use writing and reading for inquiry, learning, thinking, and communicating.

- Understand a writing assignment as a series of tasks, including finding, evaluating, analyzing, and synthesizing appropriate primary and secondary sources.

- Integrate their own ideas with those of others.

- Understand the relationships among language, knowledge, and power.

CEE suggests that students will develop the following skills:

- Use electronic environments for drafting, reviewing, revising, editing, and sharing texts.

- Locate, evaluate, organize, and use research material collected from electronic sources, including scholarly library databases; other official databases (e.g., federal government databases); and informal electronic networks and internet sources.

- Understand and exploit the differences in the rhetorical strategies and in the affordances available for both print and electronic composing processes and texts. (WPA Outcomes Statement, 2008).

Of importance here are the statements that focus on IL skills such as “finding, evaluating, analyzing, and synthesizing appropriate primary and secondary sources” and “[l]ocate, evaluate, organize, and use research material collected from electronic sources, including scholarly library databases; other official databases (e.g., federal government databases); and informal electronic networks and internet sources” (WPA Outcomes Statement, 2008). As this literature review establishes, existing research supports collaboration among librarians and faculty when teaching IL skills, but a more specific approach that recognizes the value of outcomes-based assessment will also integrate the WPA OS. For example, as early as 1989 the University of Dayton revised its general education program to include IL as part of its competency program (Wilhoit, 2013, pp. 124-125). Outside of the U. S., the University of Sydney adopted the WPA OS to its writing program, including IL as one of the five clusters on which it focused to encourage growth and learning (Thomas, 2013, p. 170). The program established three graduate attributes to include “scholarship, lifelong learning, and global citizenship,” breaking these down to five clusters to include “research and inquiry; communication; information literacy; ethical, social and professional understandings; and personal and intellectual autonomy” (Thomas, 2013, p. 170). Eastern Michigan University (EMU) also identified a need to connect outcomes with IL. EMU developed a plan to integrate first-year composition (FYC) outcomes with the IL Standards (ACRL, 2000), recognizing the need to integrate key IL concepts with the research process into their first-year writing program’s research courses (Dunn, et al., 2013, pp. 218-220).

Outcomes-based assessment is an effective means for evaluating writing programs; however, when planning for IL assessment, criteria guidelines should weigh both the reliability and validity of a tool as well as the ease of administering the assessment (Walsh, 2009, p. 19). Megan Oakleaf (2008) provides a thorough overview of three popular assessment methods including fixed-choice assessments, performance assessments, and rubrics, and then charts the advantages and disadvantages of each approach (pp. 233-253). For the purposes of this discussion, we will focus on fixed-choice assessments. The benefits of fixed-choice assessments in the form of multiple-choice tests include ease of administration and scoring, the ability to compare an individual’s pre- and post-test results, and the ability to evaluate results over time; however, one limitation of this method is the difficulty in measuring higher level critical thinking skills (Oakleaf, 2008, p. 236; Williams, 2000, p. 333). Another benefit is that pre- and post-test data results can identify both student mastery of material covered in an instruction session as well as areas of student weakness (Burkhardt, 2007, p. 25, 31). Additionally, pre- and post-test data can be compared over time to further refine the library and IL curriculum (Burkhardt, 2007, p. 25, 28). Although benefits to fixed-choice assessments are numerous, Kate Zoellner, Sue Samson, and Samantha Hines’ (2008) claims pertaining to pre- and post-assessment projects suggest that there is little or no statistical difference or significance in assessment results, which makes evident the need for continuing this “method to strengthen its reliability as an assessment tool” (p. 371). For example, Brooklyn College Library developed and administered pre- and post-quizzes within Blackboard for students in an introductory first-year composition course. Learning management systems such as Blackboard have been adopted by most academic institutions for well over a decade and have been used by many libraries as a delivery platform for IL modules and assessments. Some of the advantages of using Blackboard for IL include faculty and student familiarity with the system, convenient 24/7 access for both on and off campus students, ease of creating and revising assessment questions, automatic grading for faculty, and immediate assessment scoring and feedback for students (DaCosta & Jones, 2007, pp. 17-18; Henrich & Atterbury, 2012, pp. 167, 173; Knecht & Reid, 2009, pp. 2-3; Smale & Regalado, 2009, p. 146, 151). All students in this course attended a library instruction session and completed a research paper assignment. Students completed the pre-quiz before attending a library instruction session and prior to completing their research paper assignment. Pre- and post-quiz results revealed that although scores ranged widely, the majority of students improved their scores on the post-quiz (Smale & Regalado, 2009, pp. 148-149).

An important aspect of IL assessment is the level of faculty support and participation in these efforts. Brooklyn College Library’s positive outcomes confirm collaboration is crucial to the success of library instruction programs and can lead to a greater number of more effective programs (Buchanan, Luck, & Jones, 2002, pp. 148-149; Fiegen, Cherry, & Watson, 2002, pp. 308-309, 314-316; Guillot, Stahr, & Plaisance, 2005, pp. 242, 245). Over the years, academic librarians have consistently discussed the important role they can play by partnering with teaching faculty to integrate library instruction programs into the curriculum (Breivik & Gee, 1989; Mounce, 2010; Rader, 1975). However, an effective cross-departmental collaboration requires that college administrators and interdisciplinary committees communicate the importance of curricular inclusion and implementation of IL (See Norgaard and Sinkinson in this collection). ACRL also recognizes collaboration as a major component in exemplary IL programs (ACRL Best Practices, Category 6: Collaboration section, 2012). As noted by Katherine Branch and Debra Gilchrist (1996), community college libraries in particular “have a rich tradition of instructing students in library use with the goal of increasing information literacy and lifelong learning” (p. 476). Librarians at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College (Reynolds) have long embraced this tradition, and over the years, have identified collaboration between librarians and teaching faculty as the key element of a successful IL program. Joan Lippincott (2000) notes that there are a variety of factors that encourage success in cross-sector collaborative teams, including an eagerness to work together to develop a common mission, an interest in learning more about each other’s expertise, and an appreciation for each other’s professional differences (p. 23). Many consider integrating IL into specific courses through faculty-librarian collaboration the most effective way of improving the IL skills of students (Arp, Woodard, Lindstrom, & Shonrock, 2006, p. 20; Black, Crest, & Volland, 2001, p. 216; D’Angelo & Maid, 2004, p. 214, 216). While many publications exist on collaborative IL instruction, examples of collaborative IL assessment projects are limited (Jacobson & Mackey, 2007). However, the number of collaborative assessment case studies is growing, including Carol Perruso Brown and Barbara Kingsley-Wilson (2010), Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobsen (2010), Megan Oakleaf, Michelle S. Millet, and Leah Kraus (2011), and Maureen J. Reed, Don Kinder, and Cecile Farnum (2007).

Developing a curricular program that integrates IL skills suggests the potential exists for students to retain these skills successfully. Evidence also exists to support the targeting of first-year composition courses as an effective means for incorporating IL into the curriculum partly because first-year composition is traditionally taken by all students (Barclay & Barclay, 1994, pp. 213-214). Michael Mounce (2010) similarly focuses on IL collaboration, arguing that in the humanities, librarians collaborate most frequently with writing instructors to integrate IL into composition courses (p. 313). Additionally, Sue Samson and Kim Granath (2004) describe a collaboration among librarians, writing instructors, and teaching assistants at the University of Montana-Missoula. This collaborative effort focused on integrating a library research component into randomly selected sections of first-year composition. Assessment results from the participating sections modeled on a “teach the teacher” plan, confirm that writing instructors and teaching assistants were effective in delivering IL instruction, with the added benefit of familiarizing graduate students with the IL resources available to them (p. 150).

Existing research on IL assessment efforts further substantiates faculty-librarian collaboration as critical to successfully integrating IL into the curriculum. The literature also reveals that although IL assessment is important for measuring students’ skills, there is no consensus on the best assessment methods or instruments to implement. The academic institutions examined in the literature pertaining to IL assessment developed unique assessment plans tailored to their specific situation and student population. These examples establish the framework for this study and from which Reynolds based its IL assessment practices. The following discussion of Reynolds’ IL project serves as a model for other institutions and expands the literature on IL assessment and collaboration practices by examining the impact of embedding IL modules and assessments into 22 first-year composition classes during the spring 2012 semester.

Breakthroughs in Collaboration

Although instructional collaboration existed between librarians and faculty at Reynolds prior to the assessment, it took the form of an informal and individualized process. A major breakthrough in the development of a structured collaborative process occurred in 2008 when Reynolds developed and implemented a campus-wide Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) as a part of its accreditation reaffirmation process with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). While not directly related to the SCHEV Quality Assurance Plan mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, the QEP expanded the work the SCHEV plan began in 2000. The QEP targeted the improvement of student success in online learning as its primary focus. The QEP’s concentration on faculty development and student support was designed to have a broad reach and to impact student learning outcomes throughout the college. Because the college does not have a discrete population of students and faculty involved only in online learning, the designers of the plan were confident of its expanded impact; most Reynolds students and faculty combine online learning with on-campus classes, and thus resources migrate easily between the various course delivery options. Further, the QEP Team identified IL, as well as other core student learning outcomes for assessment within its broader plan to bridge multiple disciplines, including Writing Studies, Information Technologies, and Student Development. Members of the QEP Team, including librarians, college administrators, and faculty began to discuss how to align IL instructional materials with identified course outcomes with the following courses: College Composition, Information Technology Essentials, and Student Development. With this impetus as its starting point, the college has witnessed active, interdisciplinary collaboration in the area of IL instruction and assessment; college librarians are no longer simply dependent upon individual faculty requests for instruction and one-shot sessions.

Within the Student Learning Outcomes Assessments (SLOA) subcommittee of the QEP, librarians collaborated with both Writing Studies and Computer Science faculty to incorporate the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules into high-reach, high-impact courses within these disciplines. The modules consist of the following sections: “Topics,” “Types of Information,” “Find Books,” “Find Articles,” “Use the Internet,” “Evaluate Sources,” and “Cite Sources.” In Information Technology Essentials (ITE) 115: Introduction to Computer Applications and Concepts, faculty incorporated three of the seven modules into all class sections: “Types of Information,” “Find Articles,” and “Use the Internet.” Librarians also began discussions with writing instructors on the inclusion of all seven modules within first-year composition courses.

Development of the Collaborative Instructional and Assessment Project

During many discussions focused upon IL assessment activities, Reynolds librarians identified key guidelines for the development and delivery of content: 1) the modules should cover core IL competency skills as identified by the ACRL and SCHEV; 2) they should be comprehensive enough to cover a complete research process and be flexible enough for instructors to disaggregate the modules and incorporate them into different stages of their courses or their curricula; 3) the research guides should be easy to evaluate by instructors and easy to revise by librarians; 4) the modules should be delivered online in order to serve both on-campus and online students; and finally, 5) the evaluation process should offer ease in the administration of assessments and in the collection of data. Reynolds librarians concurred that the seven Research at Reynolds Library (2015) IL modules, along with their corresponding assessments, should be delivered through Blackboard in order to meet these articulated guidelines. Blackboard provided an efficient portal for all instructors and students to reach the modules directly through their established course sites.

With these essential guidelines in place, the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules were developed using Springshare’s LibGuides, a Web-based content management system dedicated to improving students’ learning experiences. Skill sets covered in each of the seven modules are based on ACRL’s IL Standards, SCHEV standards, and the VCCS core competency standards for IL. Because of the features provided by the LibGuides technology, the new modules are much more dynamic and interactive than the ones they replaced. These modules now include embedded videos, self-assessment activities, and user feedback options. Further, Reynolds librarians have found that they can create and update the modules’ content with great efficiency and that these modules receive positive and enthusiastic responses from faculty. The modules cover the entire research process and contain a number of tutorials to walk students through the IL process. The content for each module is as follows:

1.Module 1: “Topics” offers an overview of the research process and developing a concept map to narrow focus for a research topic.

2.Module 2: “Types of Information” includes videos and links that explain and describe the information cycle and types of sources and the differences between scholarly and popular periodicals. Module 2 also clarifies publication dates to ensure currency and timeliness of sources.

3.Module 3: “Find Books” offers tutorials in both video and alphabetic texts on how to find books using Reynolds’ online library catalog and using electronic sources such as ebooks on EBSCOhost (formerly known as NetLibrary) and Safari. Module 3 also addresses how to request titles using WorldCat and Interlibrary Loan.

4.Module 4: “Find Articles” includes videos that provide a general overview of how to search in library databases and a more specific tutorial of how to find articles in EBSCOhost databases. Module 4 also clarifies Boolean searching and locating full-text articles when Reynolds does not subscribe to a journal or does not have the full-text of an article. Additionally, Module 4 explains how to access databases when off-campus.

5.Module 5: “Use the Internet” is a comprehensive discussion about searching via the World Wide Web and briefly addresses evaluating sources. It also makes a distinction between using subscription databases and the Internet when conducting scholarly research. Module 5 includes an effective video that further discusses using search engines.

6.Module 6: “Evaluate Sources” includes a video on evaluating sources and a helpful checklist for students to follow when evaluating sources—the checklist can easily be adapted to a handout. Module 6 also addresses Wikipedia, including an instructional video and a satirical view of wikis.

7.Module 7: “Cite Sources” defines and clarifies what plagiarism is and the consequences of plagiarizing. Module 7 includes an instructional video and tips for avoiding plagiarism. Module 7’s “Cite Sources” page addresses how to cite in MLA and APA, with helpful links, handouts, and worksheets on documentation and citing.

As the discussion of consistent IL instruction within college composition courses progressed, the SLOA subcommittee reached critical points of consensus, agreeing that 1) the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules (rather than other modules created outside of the college) were the ideal instructional resource for Reynolds students; and 2) ENG 112 (the second semester college composition course) was the ideal site for this instruction because the course guides students through the research process and thus provides an effective corresponding context for the IL modules. The committee agreed that all seven modules would be integrated within the composition course.

Librarians developed a variety of multiple choice, true/false, and matching questions that align with each module’s content and that can be graded automatically through Blackboard’s testing tools. Librarians from both within and outside of Reynolds reviewed all seven modules and each module’s assessment questions to provide feedback and evaluation. The modules and questions were revised based upon these initial reviews. In addition to the assessment questions, satisfaction survey questions were developed for each of the seven modules to glean information on each module’s user-friendliness and to improve the modules. Delivered through Google Docs, these satisfaction surveys are embedded in each module and provide useful feedback from the perspectives of the student users. Finally, a screencast video was developed using TechSmith’s Camtasia Studio software, providing students with a welcome message that outlines the scope and purpose of the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules; sharing with them how to begin, navigate, and complete the modules; and encouraging them to engage actively, rather than passively, with the various resources in order to gain essential and useful skills in IL.

Methods: Collaborative Overview

As the previous discussion establishes, Reynolds librarians and faculty worked closely to improve the instruction of IL skills across the curriculum and within disciplines, and have made great strides in providing an online platform to deliver the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules to both on-campus and online students. IL skills have indeed improved at Reynolds, yet challenges exist, as Edward Freeman and Eileen Lynd-Balta (2010) confirm: “[p]roviding students with meaningful opportunities to develop [IL] skills is a challenge across disciplines” (p. 111). Despite this challenge, it is clear that providing sound IL instruction occurs in the first-year composition classroom because such instruction is determined to be a vital component to general education (Freeman & Lind-Balta, 2010, p.109). Collaborative efforts among Reynolds faculty and staff further confirm that achieving a common set of goals “goes beyond the roles of our librarians, English professors, and writing center staff; therefore, campus initiatives aimed at fostering information literacy collaboration are imperative” (Freeman & Lynd-Balta, 2010, p. 111). Although not specifically a campus-wide initiative, the Reynolds English Department has worked toward developing learning outcomes for ENG 112 based on the WPA OS (2008). The WPA OS suggests guidelines for implementing sound writing and composing practices in the FYC classroom. The Reynolds IL study focused on developing skills pertaining to “locat[ing], evaluat[ing], organiz[ing], and us[ing] research material collected from electronic sources, including scholarly library databases; other official databases (e.g., federal government databases); and informal electronic networks and internet sources” (WPA Outcomes Statement, 2008). These skills are essential not only to the writing classroom but also to other disciplines that expect students to arrive in their classrooms possessing skills to conduct research with little assistance.

During the fall 2011 semester, the English Department’s assessment committee was charged with assessing how effectively ENG 112 aligns with the teaching of IL. The QEP subcommittee recruited faculty from the writing Assessment Committee to review the modules and offer feedback from a pedagogical perspective. The writing Assessment Committee chair mapped the seven modules into the ENG 112 curriculum to provide participating faculty with guidance. Additionally, the librarians asked a number of writing instructors to review the seven library modules and to take the assessments from the perspective of a current instructor for the purposes of preparing the modules for a pilot study conducted in spring 2012. After offering feedback to Reynolds librarians and after revising the modules, the QEP subcommittee also recruited students who had successfully completed ENG 112 to review and pilot-test the modules and provide feedback. Nine students agreed to participate, and six completed the intense reviews of all seven modules successfully. Student volunteers evaluated the modules on the information and materials in each module and then completed the self-assessments to see how well they had learned the material. They then completed the feedback/satisfaction survey embedded at the end of each module. Student feedback proved to be valuable, as they offered critical reviews of the modules and the accompanying assessments from a student’s perspective.

After the initial review, receipt of feedback on the modules and consequent revision process, the project organizers recruited a sufficient number of faculty teaching ENG 112 to offer a broad spectrum of course delivery options across three campuses. The committee determined the need for a treatment group that agreed to integrate all seven modules and assessments into the course design and a control group that did not integrate the modules in any way. The composition of delivery formats for the treatment group is as follows:

- Thirteen face-to-face sections

- Two online sections

- Four dual enrollment sections (college-level courses taught to high school students in a high school setting)

- Three eight-week hybrid sections

- Nine control sections

In order to participate in the study, the treatment group faculty agreed to integrate all seven modules and have students complete the pre- and post-tests and the assessments associated with each module. In addition to a variety of course delivery formats, the study included a wide representation across Reynolds campuses to include 12 course sections on a suburban campus, four course sections on an urban campus, two course sections on a rural campus, two course sections in a virtual setting, and four course sections in a high school setting.

The break-down of delivery for the control group included sections from the urban and suburban campuses. The control group instructors agreed to administer the pre- and post-test assessments without integrating the seven modules. They taught IL skills as they normally would to their individual sections. One instructor within the control group integrated one face-to-face library instructional session for her course. The primary point to keep in mind is that the control group differed dramatically from the treatment group in that they did not take advantage of the online library research guides; this distinguishing factor becomes significant when comparing the results between the two groups.

After recruiting study participants, extensive communications occurred to introduce the project to faculty and to encourage continued participation, from initial agreement to the project’s completion. The committee provided support and resources for:

- understanding the ENG 112 Learning Outcomes;

- revising course schedules to demonstrate effective integration of the modules;

- raising awareness of which chapters and sections of the two textbooks in use at the time of the study corresponded with the Research at Reynolds) Library (2015) modules;

- understanding the technologies of how to integrate the IL Blackboard course into existing sections of ENG 112; and

- submitting pre- and post-assessment scores to the QEP coordinator.

Each participating instructor was enrolled in the Blackboard course “ENG 112 Information Literacy Project.” Specific Blackboard training included:

- Integration of pre- and post-tests

- Integration of all seven modules

- Integration of all seven assessments

- Integration of results into Blackboard’s grade book

Although most faculty at Reynolds have experience with Blackboard, the more advanced functions in the grade book or the completion of a course copy are often not familiar to all of them. Providing initial and ongoing technical support proved to be beneficial to the study and minimized frustration that often occurs with technology. In-depth training within Blackboard’s components and specifically for the grade book was important to encourage accurate sharing of data for analysis purposes.

Data Analysis: Results of the Assessment

The collaborative effort on the part of writing instructors and librarians in both instruction and assessment resulted in several important findings. Apart from the research results themselves, however, the collaboration emphasized efficiency and effectiveness in the broader assessment process. The development of clear and specific course learning outcomes, combined with well-developed instructional resources and a solid, guided assessment process, resulted in impact upon student learning. In significant ways, the assessment project highlighted essential outcomes for both the librarian and faculty researchers: effectively communicated strategies of assessment and a well-designed collaboration among a team of researchers were critical to the development, implementation, and assessment of teaching and learning.

On a fundamental basis, the assessment confirmed that the second semester composition course is an appropriate site for the instruction of IL skills. That is, students of the institution enter ENG 112 with enough foundational knowledge to serve as a building block upon which to develop their skills. At the same time, they are not yet proficient enough in research skills to meet the challenge of conducting and completing independent researched writing. Thus the institution’s efforts in mapping its general education curricula within the areas of IL were reinforced by the assessment; the results demonstrated that ENG 112 was an appropriate location for the introduction, development, and application of research and research-supported learning activities. Within this foundational course, students gain skills upon which subsequent courses and programs of study can build and strengthen research and IL skills. Further, assessment results also indicate that ENG 112 instructors are having solid and effective impact upon student learning in the area of researched writing.

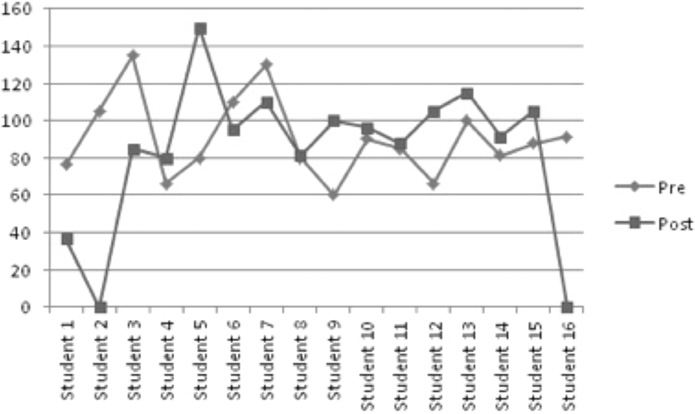

Integration of the online Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules proved to be quite successful; results indicated a significant rise in scores from pre-test to post-test in both the treatment and control groups. For example, Figure 19.1 depicts the rise in scores for a face-to-face class in which fifteen of the twenty-one students enrolled in the course showed improvement between the pre- and post-tests. Only three students showed little-to-no improvement and three others did not take the post-test. Zero scores are indicative of students who either remained in the class but did not take the post-test or students who took the pre-test but withdrew from the class prior to taking the post-test.

Figure 19.1. Comparison between pre- and post-tests (face-to-face, Spring 2012).

Although not quite as dramatic, Figures 19.2 and 19.3 also depict a marked improvement from pre-test to post-test in an additional face-to-face section of ENG 112 and in a distance learning section of the same course. In Figure 19.2, nine students improved their rest results from pre-to post-test: One student achieved the same results on both assessments, and four students attained lower scores.

Figure 19.2. Comparison between pre- and post-tests (face-to-face, Spring 2012).

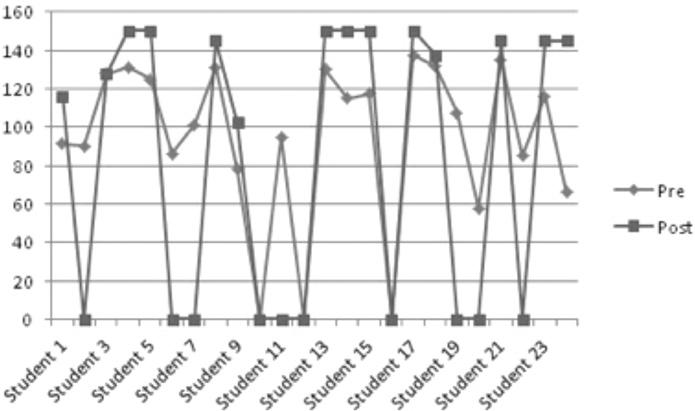

Figure 19.3. Comparison between pre- and post-tests (distance learning, Spring 2012).

Figure 19.3 highlights similar improvement in learning for distance learning students. These results indicate that the IL modules impact student learning regardless of the course delivery method. Although this course section experienced a lower rate of post-test completion than the face-to face sections, the 14 students who did complete the post-test all achieved scores that were higher than their pre-test results.

Although the two summer sessions of ENG 112 that were incorporated within the study had fewer students, the post-test results indicate that the majority of students achieved higher results in the post-test, with only one scoring below his or her pre-test results and six students achieving the same results on the pre- and post-tests. Figures 19.4 and 19.5 illustrate the increase in scores between pre- and post-tests.

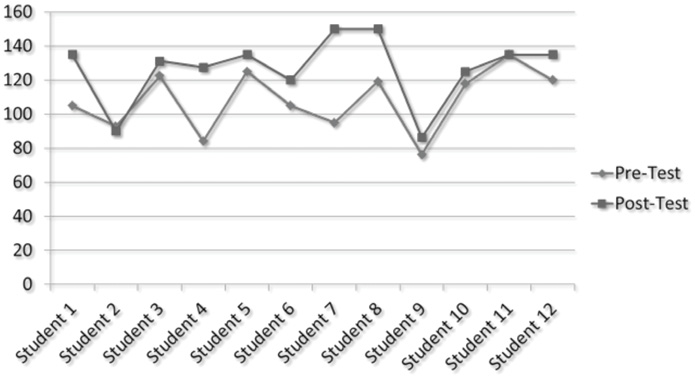

Figures 19.1 through 19.5 focus upon results within individual courses that were a part of the treatment groups. Students within the control groups were also administered the pre-and post-tests, but they received in-class IL instruction only and did not have guided access to the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules. Like their counterparts within the treatment group, the majority of students in the control group also demonstrated improvement between the pre- and the post-assessments. However, the students who had the added benefit of the seven online modules demonstrated a greater impact upon their learning outcomes. These students, regardless of the course delivery format of ENG 112 (online, hybrid, dual, or traditional), experienced much higher results within their post-assessment scores. Thus, while instructor-led efforts in the areas of research strategies and IL certainly impacted student learning, student engagement with the online, self-guided research modules yielded overall higher post-test scores. These results indicate that the students within the treatment group had developed research skills and identified effective research strategies at a rate exceeding their counterparts within the control sections. Figure 19.6 highlights this attainment of learning for both groups of students:

Figure 19.4. Comparison between pre- and post-tests (DL, Section A, Summer 2012).

Figure 19.5. Comparison between pre- and post-tests (DL, Section B, Summer 2012).

Figure 19.6. A comparison of the treatment group and the control group results.

At pre-test time, the average scores of students in the control sections versus the treatment sections demonstrated no reliable difference between the two groups. The students in the control group began at approximately the same level as those in the treatment group. Overall, students scored an average of 93.41 points (SD=21.21 points). This score represents a typical score of about 62% correct responses on the assessment survey. By the time of the post-test assessment, both the treatment group and the control group had made significant progress:

- The control group improved by 7.30 points, on average.

- The treatment group improved by 20.15 points, on average.

In other words, at the time of the post-test, the treatment group achieved a solid level of competency in research skills, with an average score of 76% within the post-assessment. The control group neared “competency,” averaging 66% of correct responses on the post-assessment.

An unanticipated outcome of the assessment was the significant impact that the African-American students within the assessment group. Figure 19.7 indicates that at pre-test time, African-American students scored significantly lower than White students. (The average scores of students self-classified as “Other” indicate no reliable difference between “Other and White,” or “Other and African-American.”) By post-test time, however, African-American students’ scores were commensurate with the scores of “Other” students. The slope of learning representing the African-American students is steeper than the slope of the other two groups. Further, the difference noted in slopes representing the learning and the attainment of skills of the African-American students and the White students is statistically significant.

Figure 19.7. Results according to ethnicity.

African-American students began the semester scoring at an average of 55% correct responses. By post-test, however, they were scoring approximately 69% correct, which is commensurate with the 74% correct average for White students and the 68% correct average for other students. By the end of the course, all ethnicities within the assessed ENG 112 classes had made progress, but African-American students had compensated for a significant initial disadvantage. The results attest to the finding that a combination of instruction within ENG 112 and the online Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules are helping to level the playing field for African-American students, at least in terms of IL skills.

In its final evaluation, the assessment results yielded several useful elements of information:

- ENG112 is having a direct and significant impact on student learning outcomes in the area of IL.

- The integration of online library research guides within ENG 112 results in even more significant gains for students in research skills.

- African-American students begin ENG 112 with IL skills that are at a disadvantage when compared to White students and to students classified as “Other.” However, African-American students make the most significant gain in learning by the end of a semester, surpass the “Other” category, and reach very close to “competency” level by time of post-test.

Concluding Comments

The study concluded at the end of the summer 2012 session with faculty submitting spreadsheets, indicating scores on both the pre- and post-tests from both the spring 2012 semester and the summer 2012 session. Full integration of the seven online modules along with assessment of each module reinforces twenty-first century IL skills based on the ACRL’s IL Standards and that also conform to the VCCS core competency standards. The results of the IL assessment at Reynolds demonstrate that students who might initially be underperforming as they enter ENG 112, will perform at equivalent or higher levels than their classmates. Not only do such positive results suggest the success of the Research at Reynolds Library (2015) modules, but they also suggest great potential for students to be successful in upper-level courses within the community college system and in four-year college and university systems. Although the data collected for this study do not extend to students beyond a two-year college, researchers can conclude that students who successfully complete the seven online library modules are more likely to persist in college to achieve greater success in 200 level courses requiring the use of IL skills based on 21st-century literacy practices. Clearly, reinforcing IL skills is relevant to the first-year undergraduate curriculum because “[t]he ideal way to produce fully capable graduates is to embed academic skills in the first-year curriculum, then continue their application, reinforcement and further development through the degree programme” (Gunn, Hearne, & Sibthorpe, 2011, p. 1). These same skills are likely to remain with them as they transfer to four-year colleges and universities. The primary goal of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the online modules, but a perhaps secondary goal to be studied further is to determine how well students retain IL skills acquired through Reynolds as they move on to 200 level courses within the community college system and beyond.

References

ACRL Best Practices Initiative Institute for Information Literacy (2012, January). Characteristics of programs of information literacy that illustrate best practices: A guideline. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/characteristics

Arp, L., Woodard, B. S., Lindstrom, J., & Shonrock, D. D. (2006). Faculty-librarian collaboration to achieve integration of information literacy. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 46(1), 18-23. Retrieved from lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? article=1022&context=refinst_pubs

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/in...racycompetency

Barclay, D. A., & Barclay, D. R. (1994). The role of freshman writing in academic bibliographic instruction. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 20(4), 213-217. doi:10.1016/0099-1333(94)90101-5

Black, C., Crest, S., & Volland, M. (2001). Building a successful information literacy infrastructure on the foundation of librarian-faculty collaboration. Research Strategies, 18(3), 215-225. doi:10.1016/S0734-3310(02)00085-X

Branch, K., & Gilchrist, D. (1996). Library instruction and information literacy in community and technical colleges. RQ, 35(4), 476-483

Breivik, P. S., & Gee, E. G. (1989). Information literacy: Revolution in the library. New York: American Council on Education and Macmillan.

Brown, C., & Kingsley-Wilson, B. (2010). Assessing organically: Turning an assignment into an assessment. Reference Services Review, 38(4), 536-556.

Buchanan, L. E., Luck. D. L., & Jones, T. C. (2002). Integrating information literacy into the virtual university: A course model. Library Trends, 51(2), 144–66. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/8454

Burkhardt, J. M. (2007). Assessing library skills: A first step to information literacy. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 7(1), 25–49. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_pubs/55/

Cameron, L., & Evans, L. (n.d.). Go for the Gold: A web-based instruction program. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications...e/cameronevans

Cameron, L., Wise, S. L., & Lottridge, S. M. (2007). The development and validation of the information literacy test. College & Research Libraries, 68(3), 229-237. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/68/3/229.full.pdf+html

DaCosta, J. W., & Jones, B. (2007). Developing students’ information and research skills via Blackboad. Communications in Information Literacy, 1(1), 16-25. Retrieved from www.comminfolit.org/index.php...=Spring2007AR2

D’Angelo, B. J., & Maid B. M. (2004). Moving beyond definitions: Implementing information literacy across the curriculum. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(3), 212-217. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2004.02.002

Dunn, J. S., et al. (2013). Adoption, adaptation, revision: Waves of collaborating change at a large university writing program. In N. N. Behm, G. R. Glau, D. H. Holdstein, D. Roen, & E. W. White (Eds.), The WPA Outcomes Statement: A decade later. (pp. 209-229). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Fiegen, A. M., Cherry, B., & Watson, K. (2002). Reflections on collaboration: Learning outcomes and information literacy assessment in the business curriculum. Reference Services Review, 30(4), 307–318. doi:10.1108/00907320210451295

Freeman, E., & Lynd-Balta, E. (2010). Developing information literacy skills early in an undergraduate curriculum. College Teaching, 58, 109-115. doi: 10.1080/87567550903521272

Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Higher Education (2000, February 3). Final report of the Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Higher Education (Rep.). Retrieved from State Council of Higher Education for Virginia website: www.schev.edu/Reportstats/final_report.pdf

Guillot, L., Stahr, B., & Plaisance, L. (2005). Dedicated online virtual reference instruction. Nurse Educator, 30(6), 242–246. doi:10.1097/00006223-200511000-00007

Gunn C., Hearne, S., & Sibthorpe, J. (2011). Right from the start: A rationale for embedding academic literacy skills in university course. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 8(1), 1-10. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol8/iss1/6/

Henrich, K. J., & Attebury, R. I. (2012). Using Blackboard to assess course-specific asynchronous library instruction. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 17(3-4), 167-179. doi:10.1080/10875301.2013.772930

Jacobson, T. E., & Mackey, T. P. (Eds.). (2007). Information literacy collaborations that work. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman.

James Madison University Libraries. (n.d.). Freshmen information literacy requirements. Retrieved from www.jmu.edu/gened/info_lit_fresh.shtml

Knecht, M., & Reid, K. (2009). Modularizing information literacy training via the Blackboard eCommunity. Journal of Library Administration, 49(1-2), 1-9. doi:10.1080/01930820802310502

Lewis, J. S. (2010). The academic library in institutional assessment: Seizing an opportunity. Library Leadership & Management, 24(2), 65-77. Retrieved from http://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.ph...view/1830/1103

Lippincott, J. (2000). Librarians and cross-sector teamwork, ARL bimonthly report, (208/209). Retrieved from https://www.cni.org/wp-content/uploa...11/07/team.pdf

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (Eds.). (2010). Collaborative information literacy assessments: Strategies for evaluating teaching and learning. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman.

Maughan, P.D. (2001). Assessing information literacy among undergraduates: A discussion of the literature and the University of California-Berkeley assessment experience. College & Research Libraries, 62(1), 71-85. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/62/1/71.full.pdf+html

Mounce, M. (2010). Working together: Academic librarians and faculty collaborating to improve students’ information literacy skills: A literature review 2000-2009. Reference Librarian, 51(4), 300-320. doi:10.1080/02763877.2010.501420

Norgaard, M., & Sinkinson, C (2016). Writing information literacy: A retrospective and a look ahead. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker (Eds.), Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines. Chapter 1. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado.

Oakleaf, M. (2008). Dangers and opportunities: A conceptual map of information literacy assessment approaches. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8, 233–253. Retrieved from http://meganoakleaf.info/dangersopportunities.pdf

Oakleaf, M., Millet, M., & Kraus, L. (2011). All together now: Getting faculty, administrators, and staff engaged in information literacy assessment. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(3), 831-852. Retrieved from http://meganoakleaf.info/portaljuly2011.pdf

Rader, H. (1975). Academic library instruction: Objectives, programs, and faculty involvement. In Papers of the fourth annual Conference on Library Orientation for Academic Libraries. Ann Arbor. MI: Pierian Press.

Reed, M., Kinder, D., & Farnum, C. (2007). Collaboration between librarians and teaching faculty to teach information literacy at one Ontario university: Experiences and outcomes. Journal of Information Literacy, 1(3), 29-46. Retrieved from ojs.lboro.ac.uk/ojs/index.php...A-V1-I3-2007-3

J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College (2010 March). The ripple effect: Transforming distance learning, one student and one instructor at a time (Quality Enhancement Plan). Retrieved from www.reynolds.edu/who_we_are/about/qep.aspx

Research at Reynolds Library (2015, June 14). Retrieved from http://libguides.reynolds.edu/research

Samson, S., & Granath, K. (2004). Reading, writing, and research: Added value to university first-year experience programs. Reference Services Review, 32(2), 149–156. doi: 10.1108/00907320410537667

Saunders, L. (2007). Regional accreditation organizations’ treatment of information literacy: Definitions, collaboration, and assessment. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(3), pp. 317-18. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2008.05.003

Saunders, L. (2008). Perspectives on accreditation and information literacy as reflected in the literature of library and information science. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(4), p. 305. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2008.05.003

Saunders, L. (2011). Information literacy as a student learning outcome: The perspective of institutional accreditation. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Smale, M. A., & Regalado, M. (2009). Using Blackboard to deliver research skills assessment: A case study. Communications in Information Literacy, 3(2), 142-157. Retrieved from www.comminfolit.org/index.php...D=Vol3-2009AR7

Thomas, S. (2013). The WPA Outcomes Statement: The view from Australia. In N. N. Behm, G. R. Glau, D. H. Holdstein, D. Roen, & E. W. White (Eds.). The WPA Outcomes Statement: A decade later. (pp. 165-178). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Virginia Community College System. (2002, July 18). Report of the VCCS task force on assessing core competencies. Retrieved from www.pdc.edu/wp-content/upload...rce-Report.pdf

WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. (2008, July). WPA outcomes statement for first-year composition. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html

Walsh, A. (2009). Information literacy assessment: Where do we start? Journal of Librarianship & Information Science, 41(1), 19-28. Retrieved from http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/2882/

White, L., & Blankenship, E. F. (2007). Aligning the assessment process in academic libraries for improved demonstration and reporting of organizational performance. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 14(3), 107-119. Retrieved from www.academia.edu/784402/Alig...al_Performance

Wilhoit, S. (2013). Achieving a lasting impact on faculty teaching: Using the WPA Outcomes Statement to develop an extended WID Seminar. In N. N. Behm, G. R. Glau, D. H. Holdstein, D. Roen, & E. W. White (Eds.), The WPA Outcomes Statement: A decade later. (pp. 124-135). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Williams, J. L. (2000). Creativity in assessment of library instruction. Reference Services Review, 28(4), 323–334. doi:10.1108/00907320010359641

Zoellner, K., Samson, S., & Hines, S. (2008). Continuing assessment of library instruction to undergraduates: A general education course survey research project. College & Research Libraries, 69(4), 370-383. http://crl.acrl.org/content/69/4/370.full.pdf+html