14: Not Just for Citations - Assessing Zotero while Reassessing Research

- Page ID

- 70139

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chapter 14. Not Just for Citations: Assessing Zotero while Reassessing Research

Rachel Rains Winslow, Sarah L. Skripsky, and Savannah L. Kelly

Westmont College

This chapter explores the benefits of Zotero for post-secondary education. Zotero is a digital research tool that assists users in collecting and formatting sources for bibliographies and notes. Existing research on Zotero reflects its influence as an efficient tool for personal research (Clark & Stierman, 2009; Croxall, 2011; Muldrow & Yoder, 2009) but has made only limited links to its use as an instructional technology for post-secondary teaching (Kim, 2011; Takats, 2009). Our study illustrates how the fruitful alliance of an instructional services librarian (Savannah), an English instructor (Sarah), and a social science instructor in sociology and history (Rachel) at Westmont College, a liberal arts college of approximately 1200 students, has led to innovative applications of Zotero beyond its typical use as a citation aid. Our research-pedagogy partnership shows how students gain when librarians and instructors share responsibility for information literacy (IL). Rather than using IL-savvy colleagues primarily as one-shot trainers, faculty can invite them to partner in using reference managers (RMs) to reframe “research” and to interact with students’ RM-accessible research choices.

Using Zotero-based research instruction in four different social science and humanities courses with 49 students total (Table 14.1), our study illustrates multiple benefits of Zotero-aided research for students’ IL development. Benefits include improving students’ source evaluation and annotation skills; enabling a transparent research process for peer and instructor review; offering a platform for collaboration among instructors; and creating student relationships across courses, including interdisciplinary connections that foster attention to discourse communities. Zotero’s ability to showcase students’ in-progress research choices allows for responses ranging from peer critique to peer emulation to instructor coaching to final evaluation. Even with such meaningful pedagogical benefits, instructors can struggle to achieve student “buy-in” if a new technique does not streamline workload. Because Zotero offers students increased citation efficiency, however, students are more willing to use it. As our study suggests, applying more of Zotero’s features than just its citation aids can make a substantive difference in students’ research practices. Indeed, our Zotero-aided collaboration reveals how teaching “traditional research methods” does not accurately reflect how students locate and interact with sources in the twenty-first century.

Why did we choose to implement Zotero in the classroom, as compared to other reference management systems? Though commonly used as an open-source citation tool analogous to EasyBib, Zotero is a more extensive reference manager (RM) that assists users in collecting, organizing, annotating, and sharing sources. Zotero captures in-depth bibliographic information beyond citation needs and allows users to revisit texts in their digital environments. These functions exceed those of EasyBib, which students use to cut and paste citations without capturing texts’ contexts. Zotero’s features mimic those of costly competitors Endnote, Papers, and RefWorks. The free RM Mendeley approximates Zotero’s features, but a comparative study of four RMs (Gilmour & Cobus-Kuo, 2011) ranks Zotero higher than Mendeley in terms of fewer errors (e.g., capitalization) per citation—1.3 vs. 1.51 respectively (see Table 14.2). The same study rates these two free RMs higher in overall performance than the for-profit RefWorks (see Table 14.3). Ongoing development of Zotero and other free RMs bears watching, given their performance quality and accessibility.

George Mason University’s Center for History and New Media launched Zotero in 2006 as an extension of the web browser Firefox. In 2011, Zotero developers offered a standalone version that extends its compatibility to Safari and Google Chrome. Zotero’s browser-centric design allows researchers to grab source citations, full-text portable document files (PDFs), uniform resource locators (URLs), digital object identifiers (DOIs), and publisher-provided annotations while browsing (see Figure 14.1). Zotero’s origin within browsers suggests assumptions about the importance of online sources in 21st-century research, and its user-friendly display mimics that of the familiar iTunes. Using rhetoric not unlike Apple’s, Zotero’s website stresses the connection between desired resources and everyday technology habits; its quick guide promotes Zotero as a tool that “lives right where you do your work—in the web browser itself” (Ray Rosenzweig Center, para. 1, n.d.). Once sources are gathered via browsers, Zotero gives users stable source access through a data cloud—a process that mimics not only iTunes but also Pinterest. Allowing users to tag and “relate” sources, add Notes, form groups, share research library collections, and conduct advanced internal searches, Zotero can be used as a works-in-progress portfolio for student research as well as a common platform for group projects. Zotero serves as a potential venue for relating multiple users, course sections, or even fields of study. Indeed, Zotero’s features demonstrate that the value of a citation lies not just in its format, but also as an important rhetorical device “central to the social context of persuasion” (Hyland, 1999, p. 342). As linguist Ken Hyland has found in examining citation patterns in the humanities and social sciences, scholars use citations not only to insert themselves into debates but also to construct knowledge by stressing some debates over others. Thus, citations are principally about “elaborating a context” that provides a basis for arguments situated in particular discursive frameworks.

Figure 14.1. A blog entry from Zotero co-director Takats (2009), grabbed with Zotero via a browser.

In addition to shaping researchers’ relationships to sources and peers, RMs such as Zotero are influencing academic journals and databases. For instance, the journal PS: Political Science and Politics started publishing abstracts in 2009 in response to RMs’ emphasis on short article descriptions. Cambridge University Press has also made their journals’ metadata more accessible for linking references to other articles (Muldrow & Yoder, 2009). Such developments emphasize how the research process itself is mutable; technological innovations and social context continually reshape research practices. As discussed by Katt Blackwell-Starnes in this collection, even Google searches can be applied and refined as part of a scaffolded pedagogy. Using Google to bridge students’ current practices with more information-literate research attentive to source trails resembles our use and assessment of Zotero.

Our assessment of Zotero extended to four classes in the fall semester of 2012 (Table 14.1), which fit into three pedagogical categories: Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC), a parallel component we term Research Across the Disciplines (RAD), and Research and Writing in the Disciplines (RID/WID). Our selection of these four courses was strategic. First, we wanted to apply Zotero in research-intensive courses with bibliography and literature review assignments engaging in scholarly conversations. Second, we wanted to test Zotero’s online sharing features with peer review exercises and group projects. Third, we wanted to do a case study in interdisciplinary collaboration. Thus, we paired the English 087 and Sociology 110 courses via a key assignment in each context (Table 14.1). To assess Zotero’s impact, we used a variety of methods including student surveys, quantitative annotation data, and assignment reflections. Our assessment suggests that Zotero can serve as both a general education aid for RAD/WAC and a catalyst for sustained RID/WID pedagogical progress—giving students the tools necessary to become web-savvy researchers and pursue long-term interdisciplinarity through personal citation libraries.

Table 14.1. Courses targeted in our Zotero-aided research teaching and assessment project

|

English 087: Introduction to Journalism

|

Interdisciplinary Studies 001: Research Across the Disciplines (RAD)

|

|

Sociology 106: Research Methods

|

Sociology 110: Social Problems

|

Evolving Concepts of IL in the Classroom

Conceptions of IL have evolved over the past decade, not only at Westmont, but nationwide as academic librarians have transitioned from a library-centric to an information-centric pedagogy. For many years, Westmont librarians perceived IL as a twofold process: help students identify library resources (e.g., books, articles) and online websites for source-based assignments, and assist students with citing sources. An “information literate” student at our institution was someone who demonstrated technological competence in navigating digital content and differentiated between MLA and APA guidelines. Librarians maintained responsibility for explicating database interfaces and search engines, but spent less time, if any, introducing sources as rhetorical artifacts and exploring how such sources were used in academic argumentation.

Central to this tools-focused teaching philosophy were the 2000 Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (IL Standards) set forth by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). The IL Standards defined IL as an individual’s capability to “recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information.” The IL Standards sought to clarify the role of IL in higher education, but the accompanying performance indicators and outcomes were often too specific (e.g., “Constructs a search strategy using appropriate commands for the information retrieval system selected [e.g., Boolean operators, truncation, and proximity for search engines; internal organizers such as indexes for books]” 2.2.d ), or broad (e.g., “Draws conclusions based upon information gathered” 3.4.c). Difficulties resulting from the IL Standards allowed librarians to cast IL as primarily concerned with students’ searching behaviors. This well-intentioned but limited understanding of the IL Standards facilitated a reliance on tools-based (e.g., JSTOR, Google, EBSCO) IL instruction at our institution for over a decade.

The alliance between students’ information-seeking behavior and tools-based instruction informed Westmont IL practices in the classroom as librarians used technology as the primary means to identify resources and manage citations. More complex IL processes—developing research questions and incorporating source material—were rarely discussed during IL sessions. Although we advocate using technology in this chapter, Zotero is not introduced as another technological competency for students to master, but as a portal through which students gain an understanding of IL as rhetorically oriented and reflective of genuine research practices.

Academic librarians may have placed too much emphasis on IL as tools-based instruction, but classroom faculty compound the problem when they teach dated models of the research process and source credibility: e.g., requiring students to format bibliographies manually and limiting the use of web-based sources, even if reliable. It concerns us that such teaching habits can mean devoting valuable time to teaching students the minutiae of varied citation styles, especially when few may retain or reuse that information. Such citation-based pedagogy seems equally misguided in light of our own reliance on RMs as researchers. Indeed, citation-based pedagogy (and related plagiarism panic) can send a dangerous message: if you cite a source correctly, you are a good researcher. This reductive definition of research resembles the current-traditional model of American education that reduced “good writing” primarily to matters of style, namely clarity and correctness (Berlin, 1987; Connors, 1997). Privileging style over substance obscures the cognitive and social aspects of research and writing, and it limits students’ ability to engage in both as crafts.

Whereas good writing is not simply a composite of stylistic expertise, likewise IL is not limited to technological competencies and citation mechanics. Scholars from varying disciplines have proffered alternatives to this conventional understanding of IL. Rolf Norgaard’s (2003) conception of IL as “shaped by writing” (i.e., “writing information literacy”) (p. 125) served as an alternate frame of reference for faculty and librarians who struggled to identify a more compelling illustration to the IL Standards. As a rhetorician, Norgaard has argued for a literacy in which texts are understood in their cultural contexts, research and writing are process-oriented, and IL extends beyond source acquisition. In this volume, Norgaard, along with librarian Caroline Sinkinson (Chapter 1, this collection), extends the conversation by critically evaluating the academic reception of his previous call to redefine IL and increase collaboration between writing instructors and librarians. Although progress is noted, Norgaard and Sinkinson acknowledge the continuing challenges of achieving campus-wide IL development and argue for broader administrative support, a redefinition of librarians’ and writing teachers’ roles, and an extension of IL concepts beyond the academy and into the public sphere.

In early 2012, Westmont library instruction program outcomes were revised to align with Norgaard’s (2003) IL perspective—writing information literacy. The decision to embrace Norgaard in lieu of the IL Standards was welcomed by librarians at our institution and provided an alternative model for advancing IL on our campus. An example outcome was that “students assess the quality of each source through a rhetorical framework (audience, purpose, genre) and evaluate its relevance to their research claim” (Westmont College Voskuyl Library, 2013). This conceptual shift improved IL communication between faculty and librarians and resonated with students across disciplines.

Whether academic communities embraced the traditional IL Standards or alternative interpretations of IL, change was imminent: as early as June 2012, an ACRL Task Force recommended revising the IL Standards. A second task force, officially charged with updating the document, followed in 2013. The resulting outcome was the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (Framework for IL) (ACRL, 2015) which was presented to the ACRL community throughout 2014. After several iterations, the ACRL Board approved the Framework for IL early 2015. The Framework for IL challenges traditional notions of IL by proffering six broad frames based on “threshold concepts,” which are “ideas in any discipline that are passageways or portals to enlarged understanding or ways of thinking and practicing within that discipline” (ACRL, 2015). These frames—Scholarship as Conversation; Research as Inquiry; Information Creation as a Process; Authority is Constructed and Contextual; Information Has Value; and Searching as Strategic Exploration—are highly contextualized, emphasizing students’ participation in knowledge creation over knowledge consumption (ACRL, 2015).

The Framework for IL emphasizes the necessary collaboration between faculty and librarians in advancing IL in the classroom. Since we instructors previously aligned our conception of IL as contextual and rhetorically oriented, the shift from our 2012 Norgaard-inspired outcomes to the Framework for IL is welcomed and will continue to support our use of Zotero in the classroom.

When we teach Zotero, we host conversations about gauging the reliability of sources and can model those evaluative practices in real time—all while demonstrating the ease of access that students have come to crave. We encourage students to consider the rhetorical choices surrounding source citation without bogging them down in details such as whether and where to include an issue number. We emphasize source selection in relation to students’ research claims and have them classify texts according to BEAM (i.e., background, evidence, argument, or method source) criteria (Bizup, 2008). Such source selection, however, is still challenging in an online environment where students must learn to sift through information and extract credible evidence, e.g., separating peer-reviewed sources on racial profiling from the unrefereed, hastily formed opinions widely available. In fact, compositionists Rebecca Moore Howard, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigue (2010) highlight significant problems in undergraduate source evaluation. Their analysis suggests that students rarely summarize cited sources and that most write from sentences within sources rather than writing from sources more holistically read and evaluated—i.e., they often quote or paraphrase at the sentence level without assessing a source’s main claims. Students’ sentence-level engagement with sources suggests that ease of access to quotable text may be the key criterion in their evaluative process, if such can even be deemed evaluative. Howard et al.’s concerns were pursued on a larger scale in the cross-institutional Citation Project study of U.S. college students’ source-based writing habits. Drawing on Citation Project data, Sandra Jamieson, in this collection, claims that most students engage sources shallowly even when they have selected suitable sources.

When taught in combination with suitable writing assignments such as scaffolded research projects (Bean, 2011), Zotero can nurture students’ rhetorical sensitivity about the nature of sources, conversations among sources, and opportunities for source integration in writing. In a study of engineering research papers, Kobra Mansourizadeh and Ummul K. Ahmad (2011) discovered that differences in how expert and novice writers employed citations signaled a need for targeted pedagogies. Without the experts’ “breadth of cumulative knowledge,” novices require explicit instruction on the different purposes and “rhetorical functions of citations” (pp. 152-161). For novices to advance, they must identify a context for their “interpretive knowledge” and make the epistemological leap from writing for themselves to writing for others in a discourse community. Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s popular textbook They Say, I Say (2009) helps novices make this leap beyond self; yet even with effective instruction, this transition is difficult. As argued by John C. Bean (2011), both conceptual and procedural difficulties with research can lead to a vicious cycle of misperception and dread for students and instructors alike (pp. 227-229). Zotero supports novices’ development both conceptually and procedurally. It gives them a central platform for building their own “cumulative knowledge.” Further, in redirecting time from formatting source citations to source selection, purpose, and rhetorical integration, Zotero refocuses novices’ energies from style to substance.

Personalized Citation Libraries and Interdisciplinarity in Research Instruction

By helping students retrieve and organize sources in individual or group libraries, Zotero sustains source accessibility and productive research habits across typical course structures. A study of undergraduates who used Zotero in a Chemical Literature course revealed that students embraced the creation of “personalized citation libraries” that strengthened their understanding of scientific literature (Kim, 2011). These libraries function as e-portfolios of research that benefit students in terms of source capture, organization, and evaluation as well as allow others to assess their choices. For example, in Savannah’s RAD course (IS 001), asking first-year students to develop Zotero libraries facilitated research organization, opportunities to name and develop their academic interests, a stable record of scholarship, and pursuit of topical inquiries across courses. In terms of support, requiring first-year students to set up Zotero libraries typically means that instructors or other partners must address first-time user challenges—e.g., browser compatibility, user errors, and Zotero library syncing. Planning to support “learning curve” pitfalls increases the likelihood that first-year students will use and benefit from Zotero throughout college.

Over time, as a mechanism for personalized citation libraries with space for shared folders, Zotero orients undergraduates toward interdisciplinary innovation. Students can relate back to archived sources when starting new projects. For instance, one student in our study kept a record of books that she did not use for her sociology paper because she thought they could be useful for a religious studies project. As instructors, we emphasize the value of saving tags and notes for future projects that explore similar themes. Since Zotero’s Notes are keyword searchable, we point out that students can use them to develop research across semesters. Once students chose topics such as immigration or foster care, we encouraged them to pursue those lines of inquiry not only in journalism but also in future social science courses.

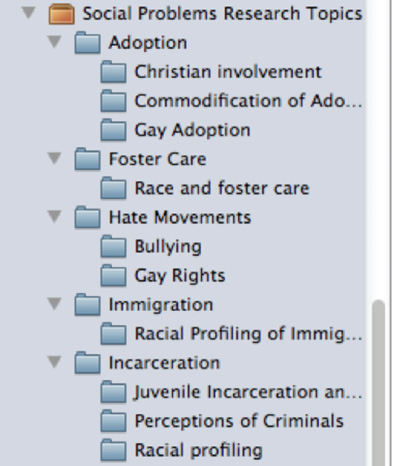

For our paired ENG 087 and SOC 110 courses, Zotero file sharing enabled interdisciplinary peer review as well as students’ self-reflection on projects’ varied aims and need for evidence. The dual-course group library, Social Problems Research Topics, was accessed by 24 users—two course instructors (Sarah and Rachel), a supporting instructor (Savannah), 13 journalism students, and eight sociology students. As library co-administrators, we established group folders for umbrella research topics: adoption, foster care, hate movements, immigration, and incarceration. We then “salted” the folders with a few sources: first, to model Zotero file sharing for students and, second, to generate topical teaching conversations. Without a particular requirement for the number of sources to gather, the 24 users contributed a total of 112 sources to the group library, i.e., an average of 4.7 sources per user.

We also assisted students in developing subfolders with relevant subtopics for focusing their projects (Figure 14.2). After sociology students noticed that the journalism students were mainly posting popular media articles, Rachel discussed with students why a media account would not provide enough evidence for a policy paper. Though not all shared sources were suitable for all projects, Rachel told the sociology students that perusing relevant media could be useful, especially in reframing their research questions and linking policy narratives to current events. In a project on cyberbullying, a student drew on Zotero library sources related to social media to complicate her initial research questions. In turn, journalism students benefitted from reviewing academic journal articles posted by sociology students whose familiarity with social problems was grounded in months of instruction in those content areas.

Figure 14.2. Subfolders developed in a Zotero group library for ENG 087 and SOC 110.

Despite the benefits of such interdisciplinary collaboration, we observed several limitations. When reviewing the shared Zotero library, we noticed that fewer journalism than sociology students were participating. In part, this imbalance is consistent with the varied development of those in an introductory versus an upper-level course. In retrospect, however, the journalism assignment (writing a feature story related to social problems) was not a natural fit for Zotero use. Since one of Zotero’s virtues is quick capture of secondary sources from databases, its limitations in collecting primary sources (e.g., the interviews conducted by journalism students and statistical data on government websites) likely contributed to journalism students’ limited Zotero use. These source-capture constraints suggest that Zotero, especially when used in groups, is better suited for assignments such as literature reviews for which secondary sources are essential. A revised version of the ENG 087 feature story assignment asks students to prepare for interviews by creating annotated bibliographies of relevant secondary literature. Such scaffolding prompts source use more suitable for Zotero and writing of more astute interview questions. This revision promotes a dialogic model of research and enhances WID development for journalists.

Notably, students initiated interdisciplinary connections we did not require. Of the 23 students introduced to Zotero in the two sociology classes, 13 (or 56.5%) used the program in other classes that semester without any such coaching, and 20 students (or 86.9%) said they planned to use Zotero in future classes. Many students organized their personal folders by topic, rather than class, suggesting that they could envision those topics crossing disciplinary boundaries. Such activity is encouraging in a liberal arts context. A junior reported that he had created Zotero folders for anticipated projects on sexuality, family formation, and civil liberties. Equipping students for sustained topical inquiry prepares them for a range of future endeavors, including graduate school research and contributing to conversations within and beyond the academy.

Watching Research Unfold: Transparency in Zotero-Aided Pedagogy

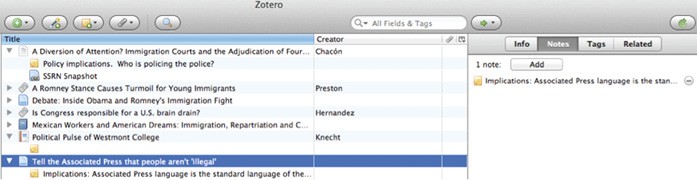

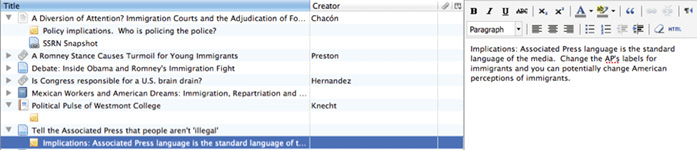

Zotero group libraries make research trails visible to faculty instructors, partner librarians, and students’ peers, thus, enabling a review process in multiple moments and models of instruction. Although some process-oriented faculty may require the creation of research logs or writers’ memos to accompany source-based assignments, few use RMs such as Zotero for research evaluation. In contrast to a traditional log or memo, limited to student self-report, Zotero group libraries publicize students’ research choices and afford access to the sources as well. Research choices may be reviewed in an instructor’s office hours when a student feels stalled; together, they can troubleshoot those choices without relying solely on the student’s memory of what has already been tried. Rather, by double-clicking on sources stored in Zotero, they can retrace existing research trails and also pursue new ones (e.g., by using peer choices as samples or by modeling strategies left untried). In effect, Zotero libraries offer an archive of student research choices that, with instructor interaction, fosters IL development. Instructor-librarian teaching partners can share access to Zotero libraries as they mentor students in IL concepts and choices. Shared IL instruction can benefit teaching faculty, instructional librarians, and students alike, and Zotero helps facilitate these opportunities by offering efficient resource management and communication tools. Zotero’s file sharing does not eliminate the need for capable research instruction. Rather, its ability to survey student researchers in motion (as demonstrated in Figures 14.3, 14.4, and 14.5) can redefine the IL roles of librarians and instructors, from one-shot source locators and citation doctors to research observers and coaches. This redefinition reflects our process orientation in IL instruction and supports the approach envisioned by the Framework for IL.

Through Zotero, students collect enough information to revisit where a source was accessed, and instructors can use this research-trail feature to introduce the idea of discourse communities. We can then reassess Zotero-gathered sources as “conversation pieces” among authors rather than static documents. We encourage this rhetorical perspective on sources by teaching Zotero’s tags and “related” features, which prompt students to trace relationships among sources. For students to develop as researchers, they must tailor source selection to their rhetorical purposes. We asked students to use Zotero’s Notes feature to explore these source relations and applications via annotation writing.

Annotating sources via Zotero’s Notes feature may be formal and standardized (responding to instructor-provided heuristics) or more informal and organic (arising from students’ inclinations). Two teaching procedures illustrate the value of instructor-guided evaluation and annotation; a later analysis of a RAD student’s extra annotations (Figure 14.6, Student I) will show a more organic response with a split evaluation strategy. After explaining concepts like “peer-reviewed” and “refereed” in reference to source credibility, Rachel gave sociology students 30 minutes to collect sources in Zotero under her supervision and to begin the work of annotation. For annotation, she introduced a writing template from They Say, I Say (Graff & Birkenstein, 2009) in which a writer summarizes what relevant sources argue (i.e., what “they say”) and then adds his or her voice to the conversation (i.e., what “I say” in response). Once students each completed a Zotero Note, they tagged it with relevant keywords linking it to related sources. Thus, Rachel introduced students to Zotero-aided annotation with a They Say, I Say protocol suited to literature review writing.

With a related teaching model, Savannah required that each RAD student upload ten sources to a Zotero folder for an annotated bibliography project. Students were asked to classify and annotate according to Bizup’s (2008) BEAM criteria, which evaluates how a source functions in the context of an argument; i.e., a source may supply background (B) information, provide evidence (E) acceptable to a particular discipline, propose a nuanced argument (A), or advance theoretical or methodological considerations (M). BEAM-based annotations not only encouraged students to relate sources to research questions, but also allowed for comparisons across sources, but within Zotero folders. In both annotation exercises, deliberative processes stress that “research” means participating in an ongoing conversation. Via its Notes feature (shown in Figures 14.3, 14.4, and 14.5), Zotero offers a consistent platform not only for organizing sources but also for assessing them with imbedded annotation. When synced consistently with the Zotero.org website via a group folder, such Notes are accessible both to the individual researcher and to peers to use as a model.

Figure 14.3. A Social Problems student’s use of a source-specific Note in Zotero.

Figure 14.4. Once selected, the user can see the full-text Note appear.

Figure 14.5. Users can also create standalone Notes related to overall research and writing plans.

Our content analysis of the RAD students’ Zotero-based annotations reflects their varied quality; yet overall, these students demonstrate attention to source summary and rhetorical contexts. While the weakest annotations simply reproduce source quotations (reflecting Howard et. al.’s 2010 analysis of students’ habitual, sentence-level source use), satisfactory annotations include accurate summaries of sources’ claims. More advanced annotations not only provide summaries but also attend to BEAM criteria or appropriateness for a student’s argument. Exceptional annotations offer summaries as well as references to both the BEAM criteria and the student’s argument. Such annotation writing redirects citation anxieties and helps students to resist “writing from sentences” habits. Students are then able to invest in summary writing and rhetorically sensitive evaluation related to their writing goals.

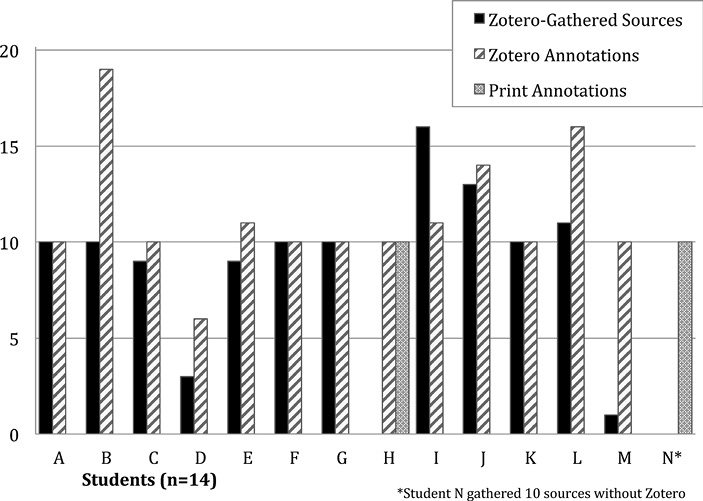

Figure 14.6. RAD students’ Zotero use in their annotated bibliography assignment.

Quantitative data related to the 14 RAD students’ source gathering and annotation writing (Figure 14.6) show promising effects for Zotero-aided research. Nearly 86% of RAD students used Zotero to complete their required annotations, while two students asked permission to write annotations in Microsoft Word. (This request reflected technological literacy difficulties in adopting Zotero.) Over two-thirds of students (71.4%) met the requirement of annotating at least 10 sources. Only two students failed to annotate at least five sources. One-third of students exceeded requirements, either gathering or annotating more than ten sources.

Atypical results merit consideration. The five RAD students who exceeded requirements in source gathering, annotation writing, or both were using Zotero. This correlation suggests that Zotero’s ease of source capture and note writing is related to a productive research process. In addition, Student I added a total of 17 annotations to only 11 gathered sources. In dividing Notes by type—either as “background,” “evidence,” and/or “argument” or, alternately, as “QUOTES” (i.e., direct quotations)—this user independently distinguishes between holistic source evaluation and source excerpts useful for quotation or paraphrase. Student I’s divided Notes method could be taught to others to reinforce this useful distinction. Overall, the RAD class data links Zotero use to more sustained, holistic, and evaluative research behaviors than those typical of undergraduates, as characterized by Howard et al. (2010) and Jamieson (Chapter 6, this collection). The results summarized in Figure 14.6 suggest that Zotero facilitates students’ research processes so that they gather more sources, annotate more sources, and craft higher quality annotations.

After students gather and annotate sources, how can peers review their choices profitably? In all four courses we taught for this assessment, our review activities were facilitated via Zotero group libraries’ shared folders, which allow students to view the research choices, tags, and source notes of their peers. When a student performed any of these actions within a group library, that action became public to course participants. While emphasizing the need for rigorous source evaluation, we used Zotero-aided peer review to promote a culture of mutual encouragement and accountability. In Savannah’s RAD course, paired students exchanged feedback on source selection and shared annotation techniques. Additionally, students described how each source would support a research argument. Although these exercises were informal, students provided suggestions and affirmations about the relationships between sources and peer-research goals—reinforcing the contexts of research choices. Sarah offered a variation on Zotero-aided peer review in an introductory composition course in spring 2013. She provided a research review handout for each student to complete first as a researcher (noting research choices and contexts), then exchange with a partner, and next complete as an evaluator of the partner’s research choices (offering at least one suggestion). During this session, reviewers had access to shared Zotero folders in order to evaluate the peers’ chosen sources, not just their annotations’ account of the sources (a limitation common in annotated bibliography reviewing). Once handouts were returned, partners discussed research choices and exited class with action plans for improved research. Such Zotero-aided peer review activities prompt student researchers to identify relevant contexts, to evaluate others’ choices, and even to mentor their peers.

Though we did not directly assess students’ research motivations, our results suggest that motivation may increase with Zotero-aided collaboration and peer review. Students learn to identify quality sources while considering what would be accepted by peers and instructors. As Betsy Palmer and Claire Howell Major (2008) contend, peer review can increase motivation, research development, and writing quality. In Sarah’s journalism class, a student who failed to complete most course assignments earned an “A” on the only assignment for which students shared sources with Zotero. This student’s atypical performance implies a potential relationship between Zotero-based collaboration and student motivation. Further study of this relationship bears consideration.

Implications and Conclusions

As our pilot study reflects, maximizing Zotero’s use in IL instruction requires strategic assignments, interdisciplinary collaboration, rigorous peer review, and strong partnerships between instructors and librarians. In our experience, Zotero-aided instruction works best in RID/RAD contexts in which students see immediate benefits for literature review annotations and source evaluation. Course and assignment suitability enhances initial buy-in to using Zotero. While it can certainly work in WAC/WID classes, Zotero pairs best with assignments that rely on secondary sources, as Sarah’s mixed experience with the ENG 087 feature assignment revealed.

Students’ class standings and disciplinary identities also matter when considering placement of Zotero-aided instruction. Indeed, sophomore- or junior-level students, most of whom had declared a major, could more readily identify the program’s potential for capstone projects and appreciate its usefulness. While seniors grasped Zotero’s benefits more quickly, they also saw fewer opportunities to use it as undergraduates. When instructing seniors with Zotero, faculty should seek ways to help students invest, e.g., coaching them about graduate school uses for their personal citation libraries. With first-year students, such as those in Savannah’s RAD class, the instructor may need to work harder to achieve buy-in: undergraduates with little disciplinary experience may lack vision for Zotero’s value.

RMs such as Zotero offer faculty and librarians a platform for productive, interdisciplinary collaboration. Partnering as teachers has shaped our assignments and the types of sources we read and teach. Our study illustrates not only our fruitful alliance but also how students win when librarians and instructors share responsibility for IL. Rather than using IL-savvy colleagues primarily as one-shot trainers, faculty can invite them to partner in using RMs to reframe research and to interact with students’ RM-accessible research choices. When instructors teach alongside librarians in the classroom, IL is reinforced as participatory and highly contextualized. Admittedly, our small liberal arts college (SLAC) context has been hospitable to such collaboration. As noted by Jill M. Gladstein and Dara Rossman Regaignon (2012), SLAC writing programs tend to be flexible and dynamic. Our local partnerships are indeed flexible enough for innovation; suitable for the liberal arts’ interdisciplinary, writing-rich curriculum; and conducive to program development with buy-in from few stakeholders.

Still, our assessment of Zotero-assisted IL instruction indicates that such work can enrich multiple curricular contexts. Zotero can help teaching partners link course sections and even academic disciplines. We suggest that it be tested further in varied program initiatives such as first-year seminars, clustered courses, learning communities, and research-intensive capstones. Regardless of context, students benefit from our IL partnerships when we make their research processes more central to instruction and connect students with experts to coach them into scholarly conversations. Yet instructors may profit most of all. Shared IL responsibility relieves faculty from carrying the full load of research instruction and reorients such instruction significantly. As we engage students in the rigors of the new Framework for IL, Zotero-based collaboration offers sustained access to IL partners and refocuses instruction on substance over style and process over tools.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/in...racycompetency

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Bean, J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Berlin, J. A. (1987). Rhetoric and reality: Writing instruction in American colleges, 1900-1985. Studies in Writing & Rhetoric. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Bizup, J. (2008). BEAM: A rhetorical vocabulary for teaching research-based writing. Rhetoric Review, 27(1), 72–86.

Blackwell-Starnes, Katt (2016). Preliminary paths to information literacy: Introducing research in core courses. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker (Eds.), Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado.

Clark, B., & Stierman, J. (2009). Identify, organize, and retrieve items using Zotero. Teacher Librarian, 37(2), 54-56.

Connors, R. J. (1997). Composition-rhetoric: Backgrounds, theory, and pedagogy. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Croxall, B. (2011, May 3). Zotero vs. EndNote. ProfHacker. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from chronicle.com/blogs/profhacke...-endnote/33157

Gilmour, R., & Cobus-Kuo, L. (2011). Reference management software: A comparative analysis of four products. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 66(66), 63–75.

Gladstein, J. M., & Regaignon, D. (2012). Writing program administration at small liberal arts colleges. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2009). They say/I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Howard, R. M., Serviss, T., & Rodrigue, T. K. (2010). Writing from sources, writing from sentences. Writing and Pedagogy, 2(2), 177–192.

Hyland, K. (1999). Academic attribution: citation and the construction of disciplinary knowledge. Applied Linguistics 20(3), 341 -367.

Jamieson, S. (2016). What the Citation Project tells us about information literacy in college composition. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker (Eds.), Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado.

Kim, T. (2011). Building student proficiency with scientific literature using the Zotero reference manager platform. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 39(6), 412-415.

Mansourizadeh, K., & Ahmad, U.K. (2011). Citation practices among non-native expert and novice scientific writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(3), 152-161.

Markey, K., Leeder, C., & Rieh, S.Y. (2012). Through a game darkly: Student experiences with the technology of the library research process. Library Hi Tech, 30(1), 12–34. doi:10.1108/07378831211213193

Muldrow, J., & Yoder, S. (2009). Out of cite! How reference managers are taking research to the next level. PS: Political Science and Politics, 42(1), 167-72.

Norgaard, R. (2003). Writing information literacy: Contributions to a concept. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 43(2), 124–130.

Norgaard, R., & Sinkinson, C. (20156. Writing information literacy: A retrospective and a look ahead. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker (Eds.), Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado.

Palmer, B., & Major, C. H. (2008). Using reciprocal peer review to help graduate students develop scholarly writing skills. Journal of Faculty Development, 22(3), 163–169.

Ray Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. (n.d.). Zotero quick start guide. Retrieved from http://www.zotero.org/support/quick_start_guide

Takats, S. (2009, August 7). Teaching with Zotero groups, or eating my own dog food, Part 1. The quintessence of ham. [blog comment]. Retrieved from http://quintessenceofham.org/2009/08...g-food-part-1/

Westmont College Voskuyl Library. (2013). Library instruction. Retrieved from http://libguides.westmont.edu/conten...74&sid=2165021