4: Evaluating Sources

- Page ID

- 100028

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction to Evaluation

In 2010, a textbook being used in fourth grade classrooms in Virginia became big news for all the wrong reasons. The book, Our Virginia by Joy Masoff, had caught the attention of a parent who was helping her child do her homework, according to an article in The Washington Post. Carol Sheriff was a historian for the College of William and Mary and as she worked with her daughter, she began to notice some glaring historical errors, not the least of which was a passage which described how thousands of African Americans fought for the South during the Civil War.

Further investigation into the book revealed that, although the author had written textbooks on a variety of subjects, she was not a trained historian. The research she had done to write Our Virginia, and in particular the information she included about Black Confederate soldiers, was done through the Internet and included sources created by groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization which promotes views of history that de-emphasize the role of slavery in the Civil War.

How did a book with errors like these come to be used as part of the curriculum and who was at fault? Was it Masoff for using untrustworthy sources for her research? Was it the editors who allowed the book to be published with these errors intact? Was it the school board for approving the book without more closely reviewing its accuracy?

There are a number of issues at play in the case of Our Virginia, but there’s no question that evaluating sources is an important part of the research process and doesn’t just apply to Internet sources. Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work. Being able to understand and apply the concept of evaluating sources is crucial to becoming a more savvy user and creator of information.

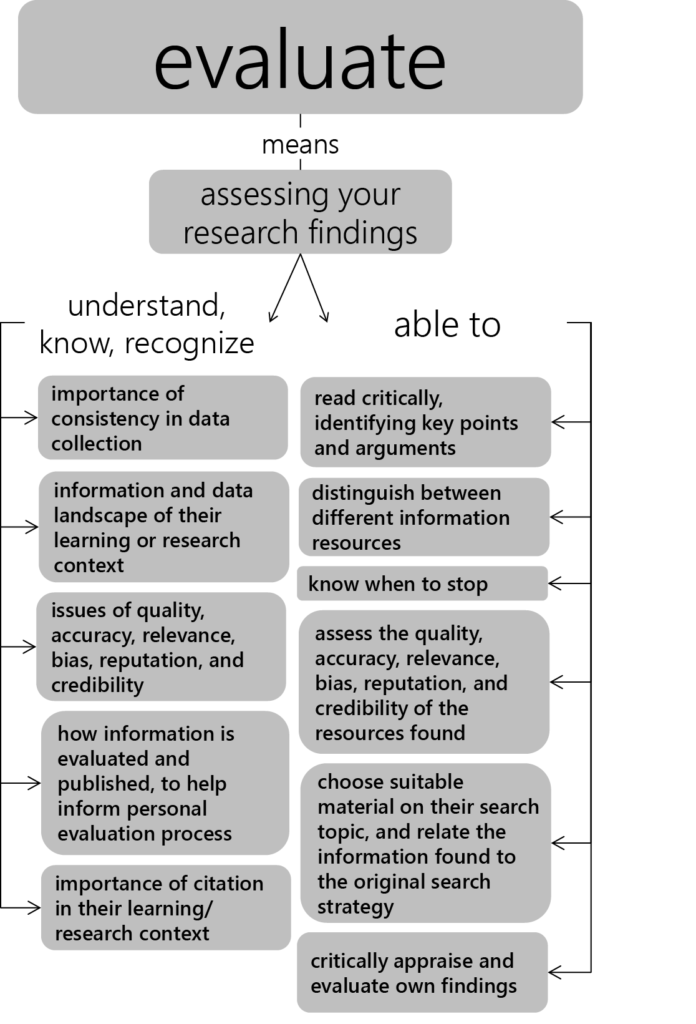

Evaluate Pillar

The Evaluate pillar states that individuals are able to review the research process and compare and evaluate information and data. It encompasses important knowledge and abilities.

They understand

- The information and data landscape of their learning/research context

- Issues of quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility relating to information and data sources

- How information is evaluated and published, to help inform their personal evaluation process

- They are able to

- Distinguish between different information resources and the information they provide

- Choose suitable material on their search topic, using appropriate criteria

- Assess the quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility of the information resources found

- Assess the credibility of the data gathered

- Read critically, identifying key points and arguments

- Relate the information found to the original search strategy

- Critically appraise and evaluate their own findings and those of others

- Know when to stop

- The importance of consistency in data collection

- The importance of citation in their learning/research context

Distinguishing between Information Sources

We read about types of sources way back in one of the first weeks of class. Here's a little refresher. Information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to evaluation. Consider the following formats.

Social Media

Social media is a quickly rising star in the landscape of information gathering. Facebook updates, Tweets, wikis, and blogs have made information creators of us all and have a strong influence not just on how we communicate with each other but also on how we learn about current events or discover items of interest.

Anyone can create or contribute to social media and nothing that’s said is checked for accuracy before it’s posted for the world to see. So do people really use social media for research? Currently, the main use for social media like tweets and Facebook posts is as primary sources that are treated as the objects under study rather than sources of information on a topic. But now that the Modern Language Association has a recommended way to cite a Tweet social media may, in fact, be gaining credibility as a resource.

News Articles

These days, social media will generally be among the first to cover a big news story, with news media writing an article or report after more information has been gathered. News articles are written by journalists who either report on an event they have witnessed firsthand, or after making contact with those more directly involved.

The focus is on information that is of immediate interest to the public and these articles are written in a way that a general audience will be able to understand. These articles go through a fact-checking process, but when a story is big and the goal is to inform readers of urgent or timely information, inaccuracies may occur. In research, news articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event.

Magazine Articles

While news articles and social media tend to concentrate on what happened, how it happened, who it happened to, and where it happened, magazine articles are more about understanding why something happened, usually with the benefit of at least a little hindsight.

Writers of magazine articles also fall into the journalist category and rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Fact-checking in magazine articles tends to be more accurate because magazines publish less frequently than news outlets and have more time to get facts right. Depending on the focus of the magazine, articles may cover current events or just items of general interest to the intended audience. The language may be more emotional or dramatic than the factual tone of news articles, but the articles are written at a similar reading level so as to appeal to the widest audience possible. A magazine article is considered a popular source rather than a scholarly one, which gives it less weight in an academic research context, but doesn’t take away the value of these sources.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts and scholars in a field and generally describe formal research studies or experiments conducted to provide new insight on a topic rather than reporting current events or items of general interest. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. This means that before an article is published, it undergoes a review process in order to confirm that the information is accurate and the research it discusses is valid. This process adds a level of credibility to the article that you would not find in a magazine or news article.

Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is not easily understood by someone who does not already have some level of expertise on the topic. Though they may not be as easy to use, they carry a lot of weight in a research context (academic or otherwise), especially if you are working in a field related to science or technology. These sources will give you information to build on in your own original research.

Books

Books have been a staple of the research process since Gutenberg invented the printing press because a topic can be covered in more depth in a book than in most other types of sources. Also, the conventional wisdom for books is that anyone can write one, but only the best ones get published. This is becoming less true as books are published in a wider variety of formats and via a wider variety of venues than in previous eras, which is something to be aware of when using a book for research purposes. For now, the editing process for formally published books is still in place and research in the humanities, which includes topics such as literature and history, continues to be published primarily in this format.

Choosing Sources

When choosing a source for your research, what criteria do you usually use? Gauging whether the source relates to your topic at all is probably one. How high up it appears on the results list when you search may be another. Beyond that, you may base your decision at least partly on how easy it is to access.

These are all important criteria, to varying degrees, but there are other criteria you should keep in mind when deciding if a source will be useful to your research.

Quality

Scholarly journals and books are traditionally considered to be higher quality information sources because they have gone through a more thorough editing process that ensures the quality of their content. Generally, you also pay more to access these sources or may have to rely on a library or university to pay for access for you. Information on the Internet can also be of a high quality but there is less of a quality assurance process in place for much of that information. In the current climate, the highest quality information, even on the Internet, often requires a subscription or other form of payment for access.

Clues to a source’s level of quality are closely related to thinking about how the source was produced, including what format it was published in and whether it is likely to have gone through a formal editing process prior to publication.

Accuracy

A source is accurate if the information it contains is correct. Sometimes it’s easy to tell when a piece of information is simply wrong, especially if you have some prior knowledge of the subject. But if you’re less familiar with the subject, inaccuracies can be harder to detect, especially when they come in subtler forms such as exaggerations or inconsistencies.

To determine whether a source is accurate, you need to look more deeply at the content of the source, including where the information in the source comes from and what evidence the author uses to support their views and conclusions. It also helps to compare your source against another source. A reader of Our Virginia may not have reason to believe the information the author cites from the Sons of Confederate Veterans website is inaccurate, but if they compared the book against another source, the inconsistencies might become more apparent.

Relevance

Relevance has to do with deciding whether the source actually relates to your topic and, if it does, how closely it relates. Some sources may be an exact match; for others, you may need to consider a particular angle or context before you can tell whether the source applies to your topic. When searching for relevant sources, you should keep an open mind—but not too open. Don’t pick something that’s not really related just because it’s on the first page or two of results or because it sounds good.

You can assess the relevance of a source by comparing it against your research topic or research question. Keep in mind that the source may not need to match on all points, but it should match on enough points to be usable for your research beyond simply satisfying a requirement for an assignment.

Bias

An example of bias is when someone expresses a view that is one-sided without much consideration for information that might negate what they believe. Bias is most prevalent in sources that cover controversial issues where the author may attempt to persuade their readers to one side of the issue without giving fair consideration to the other side of things. If the research topic you are using has ever been the cause of heated debate, you will need to be especially watchful for any bias in the sources you find.

Bias can be difficult to detect, particularly when we are looking at persuasive sources that we want to agree with. If you want to believe something is true, chances are you’ll side with your own internal bias without consideration for whether a source exhibits bias. When deciding whether there is bias in a source, look for dramatic language and images, poorly supported evidence against an opposing viewpoint, or a strong leaning in one direction.

Reputation

Is the author of the source you have found a professor at a university or a self-published blogger? If the author is a professor, are they respected in their field or is their work heavily challenged? What about the publication itself? Is it held in high regard or relatively unknown? Digging a little deeper to find out what you can about the reputation of both the author and the publication can go a long way toward deciding whether a source is valuable.

You can investigate the reputation of an author by looking at any biographical information that is available as part of the source. Looking to see what else the author has published and whether this information has positive reviews is also important in establishing whether the author has a good reputation. The reputation of a publication can also be investigated through reviews, word-of-mouth by professionals in the field, or online databases that keep track of statistics related to a journal’s credibility.

Credibility

Credibility has to do with the believability or trustworthiness of a source based on evidence such as information about the author, the reputation of the publication, and how well-formatted the source is. How likely would you be to use a source that was written by someone with no expertise on a topic or a source that appeared in a publication that was known for featuring low quality information? What if the source was riddled with spelling and formatting errors? Looking at sources like these should inspire more caution.

Objectively, credibility can be determined by taking into account all of the other criteria discussed for evaluating a source. Knowing that some types of sources, such as scholarly journals, are generally considered more credible than others, such as self-published websites, may also help. Subjectively, deciding whether a source is

credible may come down to a gut feeling. If something about a source doesn’t sit well with you, you may decide to pass it over.

Evaluating Your Findings

In the case of Our Virginia, the author used a biased source as part of her research and the inaccurate information she got from that source affected the quality of her own work. Likewise, if anyone had used her book as part of their research, it would have set off a chain reaction, since whatever information they cited from Our Virginia would naturally have to be called into question, possibly diminishing the value of their own conclusions.

Evaluating the sources you use for quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, and credibility is a good first step in making sure this doesn’t happen, but have you ever thought about evaluating the sources used by your own sources? This takes extra time, but looking at the reference list, bibliography, or notes section of any source you use to gauge the quality of the research done by the author of that source can be an important extra step.

The 5 Ws of Source Evaluation

The five Ws refer to five W questions. You’ve probably explored these W questions in other classes - but here, we’ll apply them to source evaluation.

The beauty of the who, what, when, where, and why questions of information evaluation is that they can be applied to any source. They help you determine whether a source is relevant (meets your information need) and credible (provides reliable, accurate information). Relevant, credible sources are the foundations for strong research papers. Here’s what to ask when you’re looking at a possible source:

- Who is the author of the source? Who published the source? Are they experts?

- What is the purpose of the information source?

- When was the source created? Has it been updated?

- Where can I verify the information?

- Why would I use this source instead of another one?

Let's take a deep dive into the Ws to see how to apply these questions effectively when looking at sources.

Who & What

Who

Who is the author of the source? Who published the source? Are they experts?

You should explore the “who” for every source you’re considering (examples: book, website, article, etc.). Look for author names and credentials (examples: job title or degrees). Look for professional connections that might be notable, such as membership in an organization or employment with an institution.

The who also applies to publishing. Who is responsible for publishing the source? Was it an individual posting on a personal blog? Or was it a book published by a university? The publisher can provide clues about the quality of the source and what kind of review process it’s gone through before it was released to the public.

Where to find information about the author/publisher:

- Books: Look inside the book cover or at the end of the book for a biography of the author. Check the title page or OneSearch record for publisher information.

- Newspapers/Magazines/Journals: Look at the top or bottom of an article for an author’s name and credentials (like their level of education), or information about where they work. Check the top of the page or OneSearch record for the name of the publication.

- Websites: Look for hyperlinks on authors’ names, which often link to short biographies. Look at the top or bottom of the page for an “About” section for publisher information. Don’t assume that the webmaster is also the author of the website’s content.

- Films: Look at the opening or closing credits for writer, director, and performers. For YouTube content, take a look at the channel and look for links to external pages with more information.

For all of these sources, it’s not enough to simply identify the author or publisher - you need to use that information to establish credibility. Questions you might ask yourself:

- Has the author studied and written a lot about the topic, making them an expert?

- Has the author’s life and experiences given them a unique perspective? Consider the fact that there may be different types of experts for any given topic, and the expertise you seek might differ based on the purpose of your research or how you plan to use that particular source.

- Is the publisher well-respected?

If you can’t find answers to these questions inside the source, Google the author/publisher to find any related news, credentials, or affiliations.

What

What is the purpose of the information source?

People can have lots of reasons for creating and sharing information. They may want to use that information to sell you something, to persuade you, to share research findings, to inform or entertain you. This purpose may be obvious or it may be hidden.

For example, the purpose of a well-respected newspaper like the New York Times is to report on current events in a variety of spheres (politics, culture, sports, etc.), and share informed opinions with the public. An academic journal like the Journal of the American Medical Association is designed to share original research and scholarly communication with a professional community. A website promoting tourism in a particular city will provide information portraying that place in the best possible light and carry glowing reviews and advertisements for local restaurants, hotels, and other businesses.

Your job as a researcher is to look at the source, read the language, observe the layout and context, and try to determine the source’s purpose.

When

When was the source created? Has it been updated?

Look for a date of publication or creation as you are selecting sources. Check to see if the source has been updated recently. We use the term currency to describe how up-to-date and timely an information source is. If you can't find a date of publication, look for clues in the text to figure out if the source is old. Old sources might have broken links or might refer to old news or facts.

When evaluating for currency, keep in mind that the ideal date of publication might vary depending on your topic and on the type of source you are using.

Up-to-date information is critical when you research rapidly-changing topics such as scientific information (including medical topics) and technological advancements. However, when you are researching long-standing social or political issues, or topics in history, humanities, and social sciences, the age of sources may not be as important. In these fields, interpretations change over time, but more slowly. These topics often need a balance of older and newer sources. Older sources may help you understand the historical context and reasons why we have current problems. Newer sources may describe recent events and developments related to the issue.

For sources that provide an overview or background information (e.g. encyclopedias) the facts typically remain relevant for decades.

This short video can help you reinforce the things to look for when evaluating "When."

Where

Where can I verify the information?

It may seem obvious, but when you’re selecting sources for a research assignment you want to gather credible information. How can you tell if something is credible and accurate? This is the “Where” - Where can the information be verified? Look for the following clues inside the source:

Source citations:

You are asked to cite sources in your research assignments, and your instructors are probably pretty critical if you don’t do it up to their standards. So turn that idea around. You should be just as critical of the sources you’re using, and make sure authors are telling you where they got their information and how they came to their conclusions.

Just like you, professionals and experts also research, read, and cite from others. When a source includes citations, it’s a clue that the source you are reading is based on more than just one person’s knowledge or opinions.

Citations can be formal (e.g. list of references or endnotes) and include all the details of consulted sources, or they can be informal with a good in-text citation. The best in-text citations give you enough detail to allow you to find the original source (e.g. names and publishers of research studies or hyperlinks to original sources).

But the mere fact that a source includes citations doesn’t automatically mean it’s credible. Take a look at who the author is quoting or referencing and evaluate their authority on the topic.

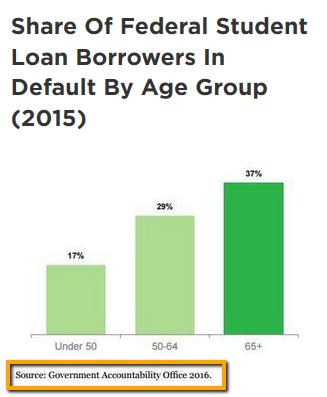

Use of data as evidence:

Data can be a powerful tool to back up claims, persuade, or illustrate a point. Writers often include statistics, charts, graphs, and other forms of evidence to support their arguments or findings. As a savvy researcher, it’s important to look carefully at data and ask questions including:

- How was the data gathered?

- Who gathered the data and is there any evidence of bias or conflicts of interest in the data collection? (e.g. an oil company who funded research showing few emission-related pollutants in the environment).

- Is there sufficient data to support the claims the author is making?

- Is the author “cherry-picking” facts that support their opinions or drawing conclusions that aren’t proven by the data collected?

Agreement among experts:

Another clue for accuracy is whether experts generally agree with the information presented in a source. There will always be hot-button issues like gun violence or immigration about which there is controversy. Even though experts might disagree about the correct solutions or policies, there will be clustering or agreement on certain ideas. If you come across a source that goes against everything you’ve read or know about a topic, apply the 5 Ws to evaluate its credibility.

Peer Reviewed Journals:

Peer-reviewed or refereed sources are articles in academic journals that have undergone an intensive screening process. The articles have been reviewed by a panel of experts in that subject area before they are published. The journal appoints this peer review panel and asks them to look for specific criteria in each article including quality of research, additions to the field of study, and making sure the research abides by the journal’s high standards.

Why

Why would I use this source instead of another one?

Your final evaluation task is to decide whether the source provides relevant information that helps you answer your research question. Keep in mind that you’ll select several sources for your research assignment, and each source should serve a specific purpose.

One source might give you background information to help you understand and focus your topic. Other sources might provide specific evidence in the form of research studies to back up claims you're making. A different source might tell the personal story of someone who has lived and experienced the focus of your topic. Notice that each source has a different purpose and provides a different type of information. By using all these sources in your research paper, you’re able to discuss history, bring in credible evidence, and show the personal side of this issue. The paper will be well-rounded and thorough.

Here are some factors to look at when thinking about relevancy and the reasons why you would use a source.:

Scope:

Scope refers to the amount of information and focus of the source. Think of a telescope. Is the source zoomed in to examine an individual or single element of your topic, or is the source zoomed out to look at the big picture examining the entire topic and the background, history, or other surrounding issues? Is the source short or long? There’s certainly more information in a 300-page book than in a 2-paragraph article.

Perspective:

When preparing a research paper, it can be helpful to select sources that represent different perspectives on an issue. Perspective describes the point of view of the source. Is the source providing an expert’s opinion on an issue, an interview with a victim or survivor of an event, or a researcher’s view based on a new study they completed?

For a controversial issue, look for sources that agree with your position on the issue, and look for a few sources that oppose your position. The best persuasive arguments have good evidence to back up claims, while still acknowledging opposing views on an issue.

Now that we’ve covered all 5 Ws, we can put our evaluation skills together to select the best sources. Measure each source you encounter using the 5 W questions (Who, What, When, Where, Why), and then compare one source against another to select the most relevant and credible information for your topic. Remember that using credible and relevant information will help you be a thorough, thoughtful, and accurate researcher.

Strategic Searching

The key to finding relevant and credible sources related to your topic is sometimes just as simple as searching in the right place. Keep in mind that you’ll have an easier time finding certain types of information using different search tools. Let’s look briefly at the differences between starting your search at Google (or any other search engine) versus starting at your college library using a library database.

|

Types of Sources |

Access |

Authority |

Relevance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

websites, statistics, images, social media, shopping, and more |

Published content like books, journal articles, and news often require payment to access |

Can range from very good to very bad and can be difficult to verify. |

Results are based on search terms and popularity of links. Some searches include irrelevant or duplicate links. |

|

Library Database |

books, ebooks, journal articles, newspapers, magazines, films, and more |

All resources are paid for by the college and provided to students for FREE. |

Authority is easier to confirm. Many sources are published through formal processes including editing before release. Database contains filters to distinguish scholarly material, including limiting results to peer-reviewed journals. |

Relevancy is controlled by using keywords. Users can focus search with limiters (e.g. subject, source type, etc.). Duplicate results are generally removed. |

Knowing When to Stop

For some researchers, the process of searching for and evaluating sources is a highly enjoyable, rewarding part of doing research. For others, it’s a necessary evil on the way to constructing their own ideas and sharing their own conclusions. Whichever end of the spectrum you most closely identify with, here are a few ideas about the ever-important skill of knowing when to stop.

You’ve satisfied the requirements for the assignment and/or your curiosity on the topic

If you’re doing research as part of a course assignment, chances are you’ve been given a required number of sources. Novice researchers may find this number useful to understand how much research is considered appropriate for a particular topic. However, a common mistake is to focus more on the number of sources than on the quality of those sources. Meeting that magic number is great, but not if the sources used are low quality or otherwise inappropriate for the level of research being done.

You have a deadline looming

Nothing better inspires forward motion in a research project than having to meet a deadline, whether it’s set by a professor, an advisor, a publisher, or yourself. Time management skills are especially useful, but since research is a cyclical process that sometimes circles back on itself when you discover new knowledge or change direction, planning things out in minute detail may not work. Leaving yourself enough time to follow the twists and turns of the research and writing process goes a long way toward getting your work in when it’s expected.

You need to change your topic

You’ve been searching for information on your topic for a while now. Every search seems to come up empty or full of irrelevant information. You’ve brought your case to a research expert, like a librarian, who has given advice on how to adjust your search or how to find potential sources you may have previously dismissed. Still nothing. It could be that your topic is too specific or that it covers something that’s too new, like a current event that hasn’t made it far enough in the information cycle yet. Whatever the reason, if you’ve exhausted every available avenue and there truly is no information on your topic of interest, this may be a sign that you need to stop what you’re doing and change your topic.

You’re getting overwhelmed

The opposite of not finding enough information on your topic is finding too much. You want to collect it all, read through it all, and evaluate it all to make sure you have exactly what you need. But now you’re running out of room on your flash drive, your Dropbox account is getting full, and you don’t know how you’re going to sort through it all and look for more. The solution: stop looking. Go through what you have. If you find what you need in what you already have, great! If not, you can always keep looking. You don’t need to find everything in the first pass. There is plenty of opportunity to do more if more is needed!

This chapter was compiled, reworked, and/or written by Andi Adkins Pogue and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Original sources used to create content (also licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0):

Bond, Emily. (2018). Evaluate the date [Video file]. https://youtu.be/jAfGCfWJfgo

Evaluate: Assessing your research process & findings. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/evaluate-assessing-your-research-process-and-findings/

Los Rios Libraries. (2020). Evaluating and selecting sources. Los Rios libraries information literacy tutorials. https://lor.instructure.com/resources/44fe428e10b347bea9892a63482f55fd?shared