Untitled Page 11

- Page ID

- 114953

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)© Ingo Gildenhard and Andrew Zissos, CC BY 4.0 http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0073.03

The setting for this episode is the Greek city of Thebes, founded by Cadmus (513–14 n.). Cadmus is by now an old man, and has abdicated the throne of his city in favour of his grandson Pentheus. Early in the reign of the young king, a wild new religious cult sweeps in from the East, that of the god Bacchus, son of the supreme god Jupiter and the Theban princess Semele. While all other Thebans welcome the new cult, Pentheus proves to be sceptical and resistant, an attitude that leads to his doom. (For further discussion of setting and mythological background, see Intro. §4). The set text can be divided into the following sections: (i) Tiresias’ Warning to Pentheus (511–26); (ii) Pentheus’ Rejection of Bacchus (527–71); (iii) The Captive Acoetes and His Tale (572–691); (iv) Pentheus’ Gruesome Demise (692–733).

511–26

Tiresias’ Warning to Pentheus

This brief but complex section includes: (i) transition from the previous story, the tale of Narcissus, whose fate the seer Tiresias unerringly foretold; (ii) introduction of the next character destined for doom on Thebes’ killing fields: the young king Pentheus, the only one left to scorn Tiresias; (iii) Tiresias’ anticipation of events to come: the clash between Pentheus and Bacchus (in essence also an encapsulation of Euripides’ tragedy Bacchae).

The narrative speeds along here: Tiresias’ prediction of Bacchus’ arrival and its fulfilment come in quick succession. This initial briskness stands in contrast to the elements of ‘slow-mo’ that Ovid will soon introduce (and which make up the lion’s share of the set text): the speeches of Pentheus and of Acoetes. In Euripides’ Bacchae, the verbal clash between Pentheus and Tiresias does not occur until some way into the drama.

511–12 cognita … ingens. These two lines form the pivot from the tale of Narcissus (just concluded) to the story of Pentheus (about to start). Ovid opts for straightforward syntax: we get two main verbs, attulerat and erat, linked by the -que attached to nomen. The design, revolving around the synonyms famam ~ nomen and vati ~ auguris (on which more below), is intricate: meritam … famam ‹› nomen … ingens form a *chiasmus; and vati attulerat ‹› erat auguris are also arranged chiastically.

A regular Latin idiom is the use of the perfect passive participle to modify a (concrete) noun where English would have, in place of the participle, an abstract noun and the preposition ‘of’. Examples include post transactam fabulam (‘after the play having been performed’ = ‘after the performance of the play’, Plaut. Cas. 84), and nuntiata clades (‘the disaster having been reported’ = ‘the news of the disaster’, Liv. 10.4). In similar fashion here the qualification of the noun res by cognita (perf. pass. part. of cognoscere, ‘get to know’ or, in the perfect, simply ‘know’) yields the sense ‘knowledge of the matter’.

The ‘matter’ referred to is the story of Narcissus and, more specifically, the fulfilment of Tiresias’ prophecy concerning the boy’s fate. As such it harks back to the beginning of that episode: enixa est utero pulcherrima pleno | infantem nymphe, iam tunc qui posset amari, | Narcissumque vocat. de quo consultus, an esset | tempora maturae visurus longa senectae, | fatidicus vates ‘si se non noverit’ inquit. | vana diu visa est vox auguris: exitus illam | resque probat letique genus novitasque furoris. (‘The beautiful nymph [sc. Liriope, mother of Narcissus] brought forth from her full womb an infant loveable even then [sc. at its birth] and named him Narcissus. When consulted about him, as to whether he would live a long time and see a ripe old age, the fate-speaking prophet [sc. Tiresias] replied: “If he shall not know himself”. For a long time the prophet’s utterance seemed an empty one, but the boy’s demise proved it true — the event, the manner of his death, the strangeness of his passion’, 3.344–50). Ovid’s linking of the two episodes in this manner raises an interesting question: ‘Will knowing about (Tiresias knowing about) Narcissus help anyone else (know themselves)? We read on (but will it help … anyone?)’. (John Henderson).

meritam … famam (notice the ‘framing’ arrangement) is the direct object of attulerat; the indirect object is vati, a 3rd declension noun, referring to Tiresias. A vates was originally a divinely inspired prophet (the meaning to the fore here); but the word also came to be used in the Augustan period as the designation of choice for poets (as opposed to the Greek loanword poeta), thereby enhancing the intrinsic metapoetic potential of prophet figures in epic narrative.

John Henderson points to an interesting twist here: ‘with famam Ovid uses this bridge between narrative layers and segments to sound the grand theme that epic poetry confers renown (see Hardie 2012) — usually, upon characters, who make a name for themselves simply by being named in their epic, but here (by surprise: Echo and Narcissus have been headlining, but they just leave backing vox and flower, disembodying into white leaves) instead upon the role of the teller in the story he foretold, and as well upon his role as stand-in mouthpiece for the bard Ovid. By implication, scorning Pentheus is scorning not just Bacchus but the power of epic, and blindly slighting the shape-shifting … Ovid. And reading (this) epic is to enter the laboratory of storytelling’.

The poetic adjective Achais -idos (f.), meaning ‘Greek’, is a Greek loan word (Ἀχαιΐς -ΐδος). It is found in Greek poetry from Homeric epic (Il. 1.254 etc.) onwards, but does not occur in extant Latin literature before Ovid (who has it again at Met. 5.306 and 15.293). Achais imparts a more elevated — and more epic — tone than would a more conventional adjective (such as Graecus, -a, -um). ‘Achaia’ (the Latin spelling, or version, through linguistic metamorphosis) was strictly speaking a region of the Peloponnese, but such synecdochical usage (one region of Greece stands for the whole) is widespread in epic poetry. In Ovid’s day, moreover, ‘Achaia’ had currency as the name of the Roman province that encompassed all of southern Greece (including the entire Peloponnese and regions immediately to the north of the Gulf of Corinth; the remaining areas comprised the province ‘Macedonia’). Such play on linguistic and geopolitical registers occurs throughout the poem and feeds into Ovid’s trans-cultural and imperialist poetics: overall, the Metamorphoses traces the transition of history and empire from Greece to Rome, with Rome (and its empire) hyperbolically conceived as tantamount to the world (see Intro. §3c). Here the geographical specification simultaneously enhances and delimits Tiresias’ fame: it knew no bounds … among the cities of Greece. The phrase per Achaidas urbes should probably be taken *apo koinou with (i) cognita res, (ii) famam … attulerat, and (iii) nomen erat … ingens. It also harks back to the opening of the Narcissus episode: Ille [sc. Tiresias] per Aonias fama celeberrimus urbes | inreprehensa dabat populo responsa petenti [‘He, renowned throughout the cities of Boeotia, gave faultless prophecies to those seeking them’, 3.339–40]. Put differently, Tiresias’ fame grows as Ovid’s narrative unfolds: whereas it was limited to Boeotia at the beginning of the Narcissus episode, at the beginning of the Pentheus episode it has reached all of Greece.

nomen has the pregnant sense of ‘famous name’, ‘renown’, ‘celebrity’; ingens makes clear that Tiresias has become the Ovidian equivalent of a Hollywood A-lister thanks to his unerring soothsaying. The genitive auguris, which depends on nomen, is used loosely as a synonym for vates in the previous verse. In republican and early-imperial Rome, an augur was a special type of religious functionary. Unlike the vates who relied on divine inspiration, an augur divined divine will (and especially their plans for the future) from signs observed in nature, often the flight- and eating-patterns of birds. But poets often used such terms more or less interchangeably in the general sense of ‘soothsayer’ (L-S s.v. augur ii), as here. Technically speaking, vates is the more appropriate label: the blind Tiresias could hardly base his predictions on the inspection of empirical signs; his access to the divine sphere — and hence inspired knowledge of the future, a prerogative of the gods — operates via a metaphysical connection. But with augur Ovid, in addition to introducing variety into his religious nomenclature, invokes a specific priesthood of Roman civic religion. By such subtle effects, Rome’s presence is felt throughout the Metamorphoses, even though the city itself will not materialize until Book 14.

513–16 spernit … obicit. The new story starts rancorously, with the verbs spernit, ridet and obicit sounding a derisive note. The shared subject of these verbs needs to be assembled from bits and pieces littered across lines 513–14: Echionides, (ex omnibus) unus, contemptor superum, and Pentheus. Our understanding of the syntax evolves as we read along. The patronymic Echionides (‘son of Echion’) could be a viable subject and seems to suffice until we reach ex omnibus unus, at which point it becomes preferable to take Echionides as standing in apposition (‘a single individual, the son of Echion …’). Two more appositional expressions follow in the subsequent line: the general attribution contemptor superum and the proper name Pentheus. Ovid thus introduces his new protagonist, the young king of Thebes, through a complex sequence of designations: we first get his lineage (he is the son of Echion), then learn that he stands apart from everyone concerning Tiresias (ex omnibus unus) and that he is a blasphemer (contemptor superum); and finally we get the actual name (Pentheus). Reshuffled, we get: ‘A single individual, Pentheus, the son of Echion, a blasphemer of the gods, still holds him in contempt …’ This build-up has an ominous effect, not merely introducing Pentheus as the principal character (the next to stamp his name on epic, to star in Ovid), but also adumbrating his downfall (the flipside of the fama factory; but infamy’s still a form of fame). Those who challenge the gods tend to meet a sticky end in the Metamorphoses (513–14 n.); the ‘piecemeal’ fashion in which Ovid introduces Pentheus here may subtly anticipate his physical disintegration at the end, where he gets torn limb from limb.

Note the placement of the verbs within a *tricolon arrangement: spernit comes at the beginning of line and clause; ridet comes at the end of line and in the middle of its clause; obicit comes at the beginning of the line and the end of the clause — and is further set off by enjambment and the abrupt *diaeresis after the first foot. The effect is to maintain focus upon Pentheus’ actions with deliberate variation. It should be noted that Narcissus too ‘scorned’ (Echo: 393 spreta) — but Pentheus ups the ante, to make a complete hatchet job of it, and of himself.

513–14 spernit … Pentheus. The conjunction tamen gives the preceding two lines a concessive force (‘Even though the story of Narcissus … Pentheus nevertheless …’). Echionides is a patronymic, which identifies an individual by a male ancestor (often his father). The patronymic is characteristic of ancient epic language, both Greek and Latin (which borrowed it from Greek). It is found from the very first line of Western literature (Hom. Il. 1.1 ‘Sing, Muse, of the wrath of Peleus’ son [Πηληϊάδεω] Achilles …’) onwards. Here the patronymic identifies Pentheus as son of Echion, one of the surviving Spartoi (Σπαρτοί, the ‘Sown-men’); his mother was Agave, one of the four daughters of Cadmus and Harmonia (see Intro. §4). The reference to Echion points back to the beginning of Book 3, where Ovid tells the story of the foundation of Thebes. Cadmus had been ordered by his father Agenor, king of Phoenicia, to search for his sister Europa (who had been abducted by Jupiter in the form of a bull). Since finding Europa proved impossible, and Agenor had forbidden his son to return without her, Cadmus was in effect forced into exile. He thus resolved to found a new city, and at length arrived at the location in Boeotia where the Delphic oracle had indicated he should do so. Thereupon he sent his comrades to fetch water, only to have them slaughtered by the dragon who dwelt in the nearby spring. Cadmus took his revenge by slaying the beast and was thereupon instructed by an anonymous voice from the sky to sow its teeth into the ground. The Spartoi soon rose from the earth in great number, but promptly began to slay each other through bloody fratricide, until only five remained. Cadmus went on to found Thebes with these five survivors, of whom Echion alone is mentioned by name (3.126 quorum fuit unus Echion — ‘one of them was Echion’). With these balancing references to Echion, Ovid imparts a sense of continuity and cohesion, while affirming the importance of lineage and Thebes’ (partial) autochthonous origins for his Theban narrative. At the same time, such references keep in view the peculiar ‘Theban condition’ — its inhabitants’ seemingly genetic predisposition to familial strife, which repeatedly brings the city to disaster. Pentheus will make much of the city’s serpentine ancestry in his upcoming speech. Indeed, ‘Echion’ derives from echis (ἔχις), the Greek term for ‘viper’, so Pentheus is quite literally ‘serpent spawn’ or, taking more liberties, ‘viper-king’ — which goes some way to explaining his bizarre praise of the serpent of Mars later on in the tale (543–48).

In ex omnibus unus the preposition is used partitively: out of all those who heard of Tiresias’ correct prediction of Narcissus’ fate only a single individual (still) holds him in contempt. Speaking more broadly, the play of ‘one versus many’ (and related motifs) recurs throughout the episode: 544 (Pentheus on the dragon of Mars) … qui multos perdidit unus …; 564–65 (Pentheus’ family trying to dissuade him from fighting Bacchus) hunc avus, hunc Athamas, hunc cetera turba suorum | corripiunt dictis frustraque inhibere laborant; 617–20 (Acoetes shouted down by his crew) hoc [probant] omnes alii …; 646 (Acoetes being beset by his crew) increpor a cunctis …; 647–48 (Aethalion mocking Acoetes after his refusal to stay at the helm) ‘te scilicet omnis in uno | nostra salus posita est’; 654–55 (Bacchus in disguise pleading with the sailors) quae gloria vestra est, | si puerum iuvenes, si multi fallitis unum?; 687–88 (Acoetes being the sole member of the crew not turned into a dolphin) de modo viginti … | solus restabam …; 715–16 (the throng of Bacchants attacking Pentheus) ruit omnis in unum | turba furens … The respective merits of the stances of individual and crowd fluctuate over the course of the narrative. At the outset, the individual (Pentheus) is misguided — both in scorning Tiresias and in refusing to permit the worship of Bacchus. In Acoetes’ tale, the opposite case arises: the ship’s crew is manifestly criminal and sacrilegious (an impia turba, 629) in its showdown with Acoetes, who alone manifests religious scruples. The final scene involves a more ambiguous situation: Pentheus, facing imminent dismemberment, at last sees the error of his ways — but too late: the divinely deranged crowd tears him into pieces, though with ‘blasphemous hands’ (manibus … nefandis, 731). John Henderson adds that ‘Ovid, in typical fashion, will show just how wooden his build-up for Pentheus is when he nevertheless adds (i) further unbelievers (batty Theban women, 4.1–4), and then (ii) the “sole” surviving Cadmeid to reject Bacchus’ godhood (Acrisius of Argos, 4.607–10), which kick-starts the next saga via the breathtakingly fake “bridge”, as Acrisius doesn’t believe in Perseus’ claim to be son of Jupiter either…! (see 559–61 n.)’.

The form superum is syncopated gen. pl. of superi, ‘the gods above’; it is an objective genitive, dependent on contemptor. The expression calls to mind the description of Mezentius as contemptor divum at Aen. 7.648, and further reminiscences of this Virgilian figure occur later in the set text (582–83, 623–25 nn.). Speaking more broadly, mortals defying gods is a prominent theme in the early books of the Metamorphoses, where an entire human race with blasphemous proclivities comes into being from the blood of giants slain while hubristically attacking the seat of the gods on Mount Olympus (Met. 1.157–62). The first representative of this particular race treated in the narrative is the vicious tyrant Lycaon, who tests Jupiter’s divinity by serving him a meal of human flesh and then attempting to murder him; it is this conduct that convinces Jupiter to eradicate the entire race of human beings (save the pious couple Deucalion and Pyrrha) in a flood of biblical proportions. It is, moreover, hardly coincidental that the giants, the human race fashioned by the Earth out of their blood, and Pentheus (via his descent from Echion) are all autochthonous, i.e. ‘born from the earth’: they are genetically predisposed (as it were) to challenge the superi (‘gods above’). Indeed, in the choral ode at Eur. Bacch. 538–44, Echion is actually said to be one of the giants who opposed the gods and Pentheus, his son, quite literally ‘born from a dragon’. In any event, contemptores superum almost invariably come to a bad end, so the phrase imparts a sense of foreboding: Pentheus’ fate, it is safe to assume, won’t be a happy one. The fact that Pentheus is a king — and as such acts as a privileged representative of Theban society towards the divine sphere — exacerbates his transgression, while creating a civic crisis (see Additional Information after 531–63 n.); but on the whole, Ovid follows Euripides in presenting Pentheus’ tale as a personal and familial tragedy rather than one of Theban society at large.

514–15 praesagaque … senis. The -que after praesaga links spernit and ridet. senis (gen. sing. of senex, ‘old man’) focalises Tiresias both as Pentheus mis-sees him as an ‘old woffler doom-monger’ and as we are to recognize him, as ‘wizened voice of authority’ (see 516–18 n.). Yes, it’s the old old story, of tradition — don’t fight it! praesaga … verba speaks both to his prophecy regarding Narcissus and to his prophetic powers more generally (on which see Intro. §5b-i).

515–16 tenebrasque … obicit. The -que after tenebras links ridet and obicit, the et links tenebras and cladem. Notice that tenebras and cladem lucis ademptae are virtually synonymous, both referring (in poetic language) to Tiresias’ blindness, and so producing a ‘theme-and-variation’ effect (cf. 646 with n.), which adds emphasis. We also have a mild instance of *hysteron proteron insofar as tenebras indicates the condition or effect, whereas cladem lucis ademptae refers to the moment of deprivation or cause. The circumstances of the blinding were recounted at 3.316–38 (see Intro. §5b-i; the key lines are also cited below). lucis ademptae is genitive of apposition (AG §343d) with cladem: lucis speaks to vision (OLD s.v. 8), ademptae (perf. pass. part. of adimo) to its loss. obicit, here in the sense of ‘to cite (before an opponent as a ground for condemnation)’ (OLD s.v. 10), presupposes an indirect object in the dative such as ei, which is easily supplied, and implies that Tiresias is in the physical presence of Pentheus. This is indeed the case, as the following makes clear, but constitutes a rather sudden and unmediated narrative turn.

516–18 ille … videres. The main clause of this segment outside the direct speech consists of ille (subject) and ait (verb), with movens being a circumstantial participle agreeing with ille and governing the accusative object albentia tempora (Tiresias is shaking his head indignantly as he speaks). albentia is present participle of albeo, modifying tempora, to which it stands in predicative position: ‘the temples white with …’ rather than ‘the white temples’. This distinction is important, as otherwise you’ll be hard put to fit in canis, an instrumental ablative governed by albentia; it comes from cani, -orum (m. pl.), strictly meaning ‘grey hair’, but here used metonymically in the sense ‘old age’. Tiresias’ visible signs of old age call to mind the reverence due to the elderly (in ancient as in modern thought), thereby underscoring Pentheus’ rude conduct. The seer ingeniously reacts to Pentheus’ contempt by reversing the terms of the latter’s mockery. As with his foretelling of Narcissus’ fate (see 511–12 n.), so here Tiresias utters a prima facie counterintuitive statement that reconceives an apparent misfortune (the loss of sight) as a blessing. The sense is that Pentheus would be better off if he too were blind because his decision to spy on the Bacchic rites will prove fatal. In broader thematic terms, Ovid subtly announces here another (fatal) case of illicit gazing, reprising the motif from the tale of Actaeon earlier in Book 3. Naturally the whole passage re-echoes with Narcissus’ brand of dysopia too — and his failure to listen.

Both esses and fieres are 2nd pers. sing. imperfect subjunctives (from sum and fio, respectively), forming a riddling present counterfactual condition (AG §517). We first get the apodosis (the exclamatory quam felix esses), then the protasis (si … fieres). Why Pentheus would be exceedingly fortunate (quam felix) if he, too, were blind is explained above.

The adjective orbus can take either an ablative or a genitive, as here with luminis huius, to indicate the thing of which one is deprived or bereft (cf. AG §349a). In post-classical Latin orbus by itself (i.e. without the genitive attribute luminis vel sim.) came to mean ‘blind’: see OLD s.v. 6, with reference to Apul. Met. 5.9, where Fortuna is called orba et saeva et iniqua (‘blind, savage, and unjust’). lumen signifies ‘eyesight’ here; it has the same sense in the prelude at 3.336–38 at pater omnipotens … pro lumine adempto | scire futura dedit poenamque levavit honore (‘But the all-powerful father granted [Tiresias] knowledge of things to come in compensation for his loss of sight and lessened [Juno’s] punishment by this honour’). In essence, we have an exchange of one type of vision (‘eye-sight’) for another (‘fore-sight’), which explains Tiresias’ use of the demonstrative pronoun huius. He may have lost one particular type of lumen (the use of his eyes), but he has gained another kind in recompense, i.e. mental il-lumin-ation/ understanding. See?

Tiresias completes the counterfactual condition with a negative result clause, ne Bacchica sacra videres. The adjective Bacchicus is one of several name-based adjectives derived from Bacchus; others include Baccheus, Bacchius, and Bacheius. The form Bacchicus is found only three times before Ovid in extant Latin, with the first two occurrences coming from fragments of early tragedies (Naevius’ Lycurgus and Ennius’ Athamas). Though a small sample size, this suggests that Ovid may have employed it here as having tragic affiliations. Bacchica sacra refers to rites performed by (usually frenzied and/ or inebriated) worshippers in honour of Bacchus; the particular allusion here is to the trieterica orgia, nocturnal rites held by the Thebans every third year on Mount Cithaeron. The adjective sacer (‘consecrated to a deity’, ‘divine’) and the associated noun sacra (‘religious rites’) are key terms that recur throughout the set text: 530 ignota ad sacra; 558 (Pentheus speaking) commenta … sacra; 574 famulum … sacrorum; 580–81 (Pentheus addressing Acoetes) ede … | morisque novi cur sacra frequentes; 621–22 (Acoetes with reference to Bacchus) non tamen hanc sacro violari pondere pinum | perpetiar; 690–91 (the end of Acoetes’ tale) delatus in illam | accessi sacris Baccheaque sacra frequento; 702 electus facienda ad sacra Cithaeron; 710–11 hic oculis illum cernentem sacra profanis | prima videt …; 732–33 talibus exemplis monitae nova sacra frequentant | turaque dant sanctasque colunt Ismenides aras. The emphasis is on the recognition of the new rites as authentic, on recognizing a divinity in human guise, and on joining up when Bacchus comes along.

Additional Information: Feldherr (1997, 47) points out that the theme of sacrifice pervades Book 3 and links the story of Pentheus with the foundation of the city at the book’s opening: ‘Images of sacrifice feature in the book’s first and last episodes and so provide a thematic frame uniting the death of Pentheus with the foundation of Thebes. After the miraculous cow has led the followers of Cadmus to the site of Thebes, the first act of the settlers is to prepare a sacrifice. It is while collecting water for libations that the colonists encounter the dragon who kills them … At the book’s conclusion not only can the dismemberment of Pentheus be compared to a Bacchic sparagmos, but the poem’s final couplet treats his death as a warning to convince the women of Thebes “to attend the new sacra, to give incense, and to cultivate the sacred altars”. In both cases the sacrifice unites its participants as members of a new community whose existence the rites themselves confirm. Thus the initial sacrifice can be clearly connected with the rituals of founding the city of Thebes itself, while the final lines make clear that it is as members of the Theban state (Ismenides) that the women will participate in Bacchic rites’. Feldherr goes on to link this concern with sacrifice in Ovid’s Theban history to the theories of the French cultural historian René Girard, who sees as the primary purpose of sacrifice not so much, or not only, communication with the gods, as the regulation of cyclical violence arising within any community as a result of competition. Naturally, any variety of human, and therefore corrupted, sacrifice must also taint the foundation it may bless — with tragedy (Zeitlin 1965).

519–23 namque … sorores. Tiresias anticipates the arrival of Bacchus in 519–20 and then goes on to spell out with a conditional sequence what will happen to Pentheus if he fails to honour the new god. The two parts of the sentence are loosely linked by the connecting relative quem (= et eum) at the beginning of line 521. The main verb of the first half is aderit; the main verbs of the second half are spargere and foedabis.

519. The archetype of namque dies aderit is the famous Homeric expression ἔσσεται ἦμαρ ὅτ’ ἄν … (‘the day shall come when …’, Hom. Il. 4.164). namque (‘for indeed’, ‘for truly’) is ‘an emphatic confirmative particle, a strengthened nam, closely resembling that particle in its uses, but introducing the reason or explanation with more assurance’ (L-S s.v.). The antecedent of the relative pronoun quam is dies, whose gender can be either masculine or feminine: when used of a fixed or appointed day, as here, it is feminine (AG §97a). In terms of syntax, quam functions both as the accusative object of auguror and as the subject accusative of the indirect statement introduced by auguror (the infinitive being esse). The verb auguror is a deponent version of the more usual auguro, with no difference in sense. The adverb procul is the predicate of quam: ‘… which, I foretell, is not far off’.

520 qua … Liber. The antecedent of qua (an ablative of time) is again dies. Tiresias’ use of the subjunctive veniat could be a modest touch reflecting the seer’s religious scruples (i.e. he opts for a potential subjunctive rather than future indicative), but that would be hard to square with the forcefulness of the preceding namque dies aderit. It may rather be that the present subjunctive (which in any case carries an intrinsic future force) was regular to express a solid future assumption in a temporal clause determining an antecedent, as here: cf. Liv. 8.7.7 dum dies ista venit qua … exercitus moveatis (‘until that day comes on which you move the army’). Some scholars have argued for the existence of a ‘prospective’ or ‘anticipatory’ subjunctive in Latin (as in Greek), though the small number of examples adduced, and the fact that they are restricted to subordinate clauses, leaves the matter uncertain.

The god Bacchus (Greek Dionysus) is variously referred to in Latin epic: Liber is one of his several poetic designations. Originally an Italian fertility god, Liber (the name signifies ‘free’) came to be associated with Bacchus despite the apparent lack of any original association with wine (see Bömer on Ov. Fast. 3.512). novus can mean ‘new’, but also ‘strange’ (OLD s.v. 2). With respect to the former sense, Liber/ Bacchus is the most recent addition to the divine pantheon (see Intro. §5b-iii), as well as ‘the big new thing’ in Book 3. With respect to the latter sense, he is a god with an unusual pedigree: while partially of Theban origin — a little earlier in the poem Ovid recounts his sensational double birth arising from the union of Jupiter and Cadmus’ daughter Semele (3.310–15; see Intro. §5b-iii) — he returns to his native city from the East as a ‘newcomer’. The themes of unfamiliarity, newness, and arrival from foreign parts recur throughout the episode, as Bacchus establishes his new cult against the resistance of his cousin Pentheus (the son of Cadmus’ daughter Agave): 530 ignota … sacra; 558 commentaque sacra; 561 advena; 581 moris … novi … sacra; 732 nova sacra. Speaking more broadly, the adjective novus is a keynote of the whole poem, which begins with in nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas | corpora (‘my mind carries me to tell of forms changed into new bodies, 1.1–2); newness is of course intrinsic to metamorphosis, and there is a strong hint of literary novelty in this declaration as well. In Roman culture more generally, though, ‘newness’ was often seen as threatening venerated tradition, so that the connotations of novus were decidedly ambivalent. res novae meant ‘revolution’, and this is precisely what Ovid’s Pentheus fears (as indeed does Euripides’ Pentheus, who speaks of νεοχμὰ … κακά [literally ‘new evils’, often translated ‘revolution’] at Bacch. 216).

The name-based adjective Semeleius, -a, -um is derived from Semele (Σεμέλη), the mother of Bacchus. The use of a name-based adjective in agreement with its noun rather than noun + genitive, which we would expect in prose, is typical of epic language; the usage with proles is formulaic: earlier in the poem, Ovid has Clymeneia proles (of Phaethon, son of Clymene, 2.19) and proles Stheneleia (of Cycnus, son of Sthenelus, 2.367); later in the set text we will see proles Mavortia (of the Spartoi, 3.531). Note that Semeleia scans ⌣ ⌣ — ⌣ ⌣, with the third ‘e’ long as representing the long Greek vowel ‘êta’ (η).

521–23 quem … sorores. The relative pronoun quem (referring back to Liber, the last word of the previous line) is a ‘connecting relative’ (equivalent to et eum; cf. AG §303) and accusative object of the verb of the nisi-clause, i.e. fueris dignatus. Tiresias here uses a ‘future more vivid’ conditional sequence (AG §516.1), with future perfect in the protasis (fueris dignatus) and future in the apodosis: spargêre (= spargêris, i.e. 2nd pers. sing. fut. indic. pass.: ‘you will be scattered’) and foedabis.

The protasis of the condition, i.e. the nisi-clause, is less complicated than it might seem at first glance. Its verb is the future perfect periphrastic fueris dignatus, from the deponent dignor. (The regular form for the future perfect as given in grammars would be dignatus eris, i.e. perf. pass. part. + a future form of sum; alternatively, Latin writers could use the future perfect form of sum, as Ovid does here). dignor, a transitive verb, is constructed with its own object in the accusative and an objective ablative (connected with the adjective dignus that the verb implies): ‘to deem x (acc.) worthy of y (abl.)’. templorum is a genitive of definition with honore: ‘the honour of temples’ is concrete advice; Tiresias is suggesting the building of such to honour Bacchus.

The indeclinable mille modifies locis (ablative of place). lacer, which prefigures 722: lacerata est [sc. manus], stands in predicative position to the subject of the sentence (i.e. you): ‘torn to pieces, you will be scattered …’ Several stylistic touches turn this into a particularly macabre visualization of Pentheus’ gruesome end. The *hyperbaton mille … locis underscores the shocking hyperbole of mille, which anticipates the ‘vehicle’ of the simile used by Ovid to cap the account of Pentheus being ripped to pieces: a tree shedding its leaves in autumn (729–31). As Keith (2002, 267) points out, the sound of the Latin spargere recalls the Greek technical term for ritual dismemberment of the Bacchic kind, i.e. sparagmos. Listen. Can you already hear the serpent spawn (513–14 n.) being torn to bits and sprayed across mille locis s-anguine s-ilvas?

Gore (sanguine) is a recurrent motif of the Pentheus episode. In fact, the set text is among the most ‘gore-nographic’ portions of the Metamorphoses, offering the ancient epic equivalent of a Hollywood splatter-film. The verb foedabis (‘you shall defile/ pollute’), made conspicuous by enjambment, contributes to the effect: it rhetorically turns the victim of dismemberment into the perpetrator of a religious offence, a prospect that Tiresias seems to dwell on with a measure of spondaic foreboding (foedabis scans — — —). After silvas, we get two more alarming accusative objects of foedabis: his mother Agave (matrem) and maternal aunts Autonoe and Ino (matris sorores), who, as the unwitting perpetrators of his dismemberment, will be splattered with their proles’ blood; his grim death will thus not only befoul the natural world, it will also pollute — both metaphorically and literally — kinship relations. The recurrence of the same word in different cases (here mater, which occurs first in the accusative, matrem, then the genitive, matris) is called *polyptoton. Here it underscores the primal horror of Pentheus’ fate: he is going to be torn apart by relatives normally associated with love, tenderness and nurturing: his mother and maternal aunts.

Note that, in addition to polyptoton, matrem and matris sorores are linked by correlating -que … -que. This correlating usage (in which the first -que is, strictly speaking, redundant) is a mannerism of elevated epic language that is not found in normal prose usage. It is generally used to connect a pair of words or expressions that are parallel in form and/ or sense, often terms designating family relations, as here. The device goes back to Ennius, who probably introduced -que … -que in imitation of Homeric τε … τε. It is metrically convenient, since the particle -que scans short (AG §604a.1), and so is particularly frequent at the close of the verse. Further occurrences of correlating -que … -que in the set text can be found at 529, 550, 558, 609, 618, 645.

524. Tiresias’ solemn one-word declaration eveniet (‘It shall come to pass!’) is abrupt and unequivocal, dispensing with the conditionality of his earlier formulation. Metre underscores the dramatic exclamation: eveniet scans as a choriamb (— ⌣ ⌣ —), and is marked off by a sharp trithemimeral *caesura, which pause enables the force of the utterance fully to sink in. eveniet is followed by additional future indicatives (dignabere, quereris) that reinforce the sense of certainty.

Hard on the heels of spargere (522), we have another alternative 2nd pers. sing. fut. indic. pass. form in dignabere (i.e. equivalent to dignaberis). The word numen is etymologically connected to nuto (‘nod’), and speaks to divine will (so, for example Cicero speaks of numen et vim deorum, ‘the will and power of the gods’, Nat. D. 2.95). Over time, however, it came to be used as a virtual synonym of deus (‘god’), and that is the sense of the term here, as again at 560.

525. The verb quereris (2nd pers. sing. fut. indic. pass. of the deponent queror, ‘to lament’) governs an indirect statement with me as subject accusative and vidisse as infinitive. With sub his tenebris (‘in this darkness’, referring to blindness), Tiresias picks up (echoes) the idiom of Pentheus’ taunt in 515–16 (tenebrasque et cladem lucis ademptae | obicit): the deictic adjective his is an explicit gesture back to it. The ability to see (vidisse) that Tiresias mentions here is his prophetic vision: he ominously declares that Pentheus will lament that he, the seer, has seen ‘only too well’ (nimium, literally ‘excessively, too much’).

526 talia … natus. The subject of the clause is Pentheus, designated Echione natus, a poeticism combining the past participle of nascor and an ablative of origin without a preposition (AG §403a): ‘born of (i.e. son of) Echion’. It is equivalent to the patronymic Echionides used earlier (513 with n.). The two references to Pentheus by way of his father’s name (and hence his chthonic origins as a descendant of the serpent of Mars) provide a fitting frame for the opening encounter between the prophet and the king.

The present tense of the circumstantial participle dicentem, which modifies an implied eum (sc. Tiresias), indicates that the action of the participle and the main verb proturbat are contemporaneous. Put differently, Pentheus rudely pushes Tiresias away while he is still speaking, thereby supplementing the verbal taunts of 514–16 with physical abuse.

Additional Information: Ovid uses the verb proturbat only twice in the entire poem, here and at 3.80 with reference to the dragon of Mars (obstantis proturbat pectore silvas, ‘he sweeps down with his breast the trees in his path’). This is part of a broader strategy of using lexical and thematic reminiscences, along with other effects, subtly to remind the reader of Pentheus’ serpentine lineage. You might look for sibilant hissing in his diction (e.g. 543–45 with n.); an inclination towards meteoric anger (cf. 3.72 where solitas … iras identifies anger as a hallmark of the dragon’s mental disposition); fearful, flashing eyes that express that anger (577–78 with n.). More subtly, Ovid unleashes a pair of similes in which the serpent and Pentheus are likened to rivers (568–71 n.).

527–71

Pentheus’ Rejection of Bacchus

527–30 dicta … feruntur. After the opening confrontation between Pentheus and Tiresias, designed to set the scene, these four transitional verses are all action. The syntax is paratactic throughout, with barely a whiff of subordination: sequitur, aguntur, adest, fremunt, ruit, feruntur — all are (indicative) verbs of main clauses; the whiff is the participle mixtae. Ovid manages to generate a sense of the spirit of the Bacchic revelry he is depicting by such touches as the polysyndetic profusion of -que and the matching choriambic openings of 528 (Liber adest) and 529 (turba ruit).

527. The initial dicta fides sequitur is a variation on verba fides sequitur at Fast. 1.359. In both cases fides means ‘proof, confirmation’ (OLD s.v. 4a). dicta is n. pl. acc. of the perf. pass. part. of dicere: ‘the things that have been said’, or ‘the pronouncement’ (the English noun ‘dictum’ has the same derivation). Note the playful word order: from a formal point of view, fides does what Ovid says it does: it ‘follows’ dicta in the verse. Derived from the perfect participle of respondere (‘answer’), the noun responsum can, as here, have the technical sense of ‘an answer given by an oracle or soothsayer’ (OLD s.v. 2a). Allow yourself a little leeway in translating aguntur: ‘actually happen’ or even ‘come true’.

As at 511, the diction echoes the beginning of the Narcissus episode: Ille [sc. Tiresias] per Aonias fama celeberrimus urbes | inreprehensa dabat populo responsa petenti; | prima fide vocisque ratae temptamina sumpsit | caerula Liriope (‘he, of stellar renown through all the Boeotian towns, gave unerring responses to the people who sought them; the first to put his trustworthiness and truthful utterance to the test was the river-nymph Liriope’, 3.339–42). Tiresias, then, has an impressive ‘track record’ in prophecy. Ovid is telling you, he should be listened to.

How much time has elapsed from Pentheus thrusting away of the prophesying Tiresias in 526 and the realization of the latter’s prophecy as announced in the following verse? Not much, judging from the present tense of sequitur and aguntur. Likewise, the emphatic Liber adest in 528 suggests the arrival of Bacchus is almost instantaneous, as sudden as an epiphany. The ‘prologue’ has come to an end; hey presto! The action starts.

528. The compact declaration Liber adest scans as a choriamb (— ⌣ ⌣ —), thus corresponding metrically to and recalling (as well, of course, as beginning to fulfil) the pithy opening of 524 eveniet! For Liber, designating Bacchus, see 520 n.

The -que displaced onto festis links the verbs adest and fremunt. festis speaks to the festive, even joyful, atmosphere of the proceedings at this point. Onomatopoeic ululatibus is used here of ritual howling: when on earth, the god Bacchus was said to be accompanied by bands of women called Maenads (Greek μαινάδες or ‘raving ones’) who danced riotously and emitted frenzied cries (ululatus) in his honour. Add to this the clashing of cymbals and the beating of drums (532–34 n.), and it is safe to say that the region is abuzz with the arrival of Bacchus and his raucous entourage. The *alliteration festis… fremunt (continued by feruntur in 530) nicely reinforces this impression. As Weber (2002, 329) points out, the ‘verb fremere is something of a vox propria for the Bacchic roar; [it] is probably cognate with Greek βρέμειν and, hence, with Dionysus’ epithet Bromius’. Note that agri is meant ‘locally’ here, i.e. the land in the vicinity of Thebes (as opposed to the city itself), but also more broadly the countryside as the characteristic location of Bacchic revelry and the scene for the showdown smithereens.

529 turba ruit. The Theban population rushes out of the city en masse, to welcome the new deity and join in the riotous cult activity. Note that the mood-setting verse opening is again choriambic (— ⌣ ⌣ —), rhythmically echoing the start of the previous line and reinforcing the relationship of cause (Liber adest) and effect (turba ruit). John Henderson adds: ‘Ovid adapts the epic hexameter to mood-set “release inhibitions” — and join (have us one and all join in with) the Bacchic choir (530). Pentheus is to become a text for worshippers to hymn the power of their awesome god for ever after, amen’.

529–30 mixtaeque … feruntur. The -que after mixtae links ruit and feruntur. Ovid creates something of a polysyndetic onslaught here, with the following two instances of correlating -que … -que linking, in the first instance, matres and nurus (‘mothers and young married women’ or, more specifically, ‘mothers and daughters-in-law’ being a poetic combination, tantamount to specifying ‘women’) and, in the second, vulgus and proceres. The keynote of the sentence is mixtae: under the influence of Bacchus social distinctions collapse. Ovid first focuses on gender (viris, matres, nurus), then on socio-economic status (vulgus, proceres). Note that the -que after vulgus scans long by position before the two consonants of the following word.

The life- and culture-changing arrival of the new god inaugurates a hitherto unknown cult, whence the ignota … sacra to which the Thebans flock (in this sense, ignota harks back to 520 and Bacchus/ Liber’s attribute novus). Passive forms of fero frequently have the ‘middle’ sense ‘carry oneself on’ (i.e. ‘proceed’), as here with feruntur; but there is often a hint of an external as well as internal impetus. Hence, in contrast to the active ruit of the previous line, the passive form suggests that the revellers are carried along in their ecstasy, i.e. have shed part of their rational agency. This is a subtle reminder that Bacchus, like few other divinities, will infiltrate the mind and induce altered states of consciousness — a quasi-metamorphic point that bears on the grim conclusion of the episode.

Pentheus attempts to stem the Bacchic ‘invasion’ of his city — or, rather, the mass exodus of the Theban citizenry to the countryside to partake in the new rites. He launches into a passionate speech that rings the changes on various rhetorical registers. It falls into five parts: (i) Three rhetorical questions, addressed to the citizens of Thebes (531–32 Quis furor, anguigenae … attonuit mentes?; 532–37 aerane tantum … tympana vincant?; 538–42 vosne, senes, mirer … vosne, acrior aetas …?); (ii) Promotion of the dragon of Mars as exemplum, interspersed with imperatives (543 este, precor, memores; 545 sumite; 546 vincite; 547–48 pellite … et … retinete); (iii) A series of conditions, (counterfactual) wishes, (self-)exhortations, and normative statements (548 si … vetabant; 549–50 utinam … diruerent … sonarent; 551–52 essemus … querenda, non celanda foret, … carerent); (iv) Anticipation of the events to come in the indicative, with reference to Bacchus and himself, with a parenthetical imperative dismissing his audience (553 a puero Thebae capientur inermi …; 557 quem … ego … (modo vos absistite) cogam); (v) A final rhetorical question, which Pentheus addresses to himself, in the 3rd person, above all (561 Penthea terrebit cum totis advena Thebis?).

Within the literary universe of the Metamorphoses the speech clearly fails to achieve its objective. The parenthetical imperative in 557 (modo vos absistite) all but admits defeat, as Pentheus has started to realize that he will be in this fight more or less on his own. The speech, then, indirectly chronicles Pentheus’ growing isolation from the rest of the citizen body and his desperate and delusional identification with Thebes, culminating in the final Caesarian gesture of speaking of himself in the 3rd person. Not only does Pentheus fail to win over his internal audience, but members of the latter actually endeavour to dissuade him from his intended course of action (as indicated at 564–65). The speech is thus not directly pertinent to the action; Ovid uses it rather to elucidate aspects of Pentheus’ character. The literary inspiration for the speech comes from the opening of Euripides’ Bacchae, in which Pentheus, likewise without success, rebukes Cadmus (accompanied by Tiresias) as he leaves the city to join in the Bacchic rites (everyone else has evidently already left): ‘I see … my own grandfather — what a ridiculous sight! — playing the Bacchant, complete with wand! Sir, I am embarrassed by the very sight of you — you old fool. Shake off that ivy! Rid your hands of the thyrsus, grandfather!’ (Eur. Bacch. 248–54).

Ovid’s Pentheus addresses a much larger group: the male citizens of Thebes. The exclusion of women from this expanded group is noteworthy, for two reasons. As Ovid has just pointed out, the followers of Bacchus flooding out of the city are an indiscriminate mixture of all age groups and of both genders, across class boundaries (529–30); if anything, the spotlight is on the women. And in Euripides’ Bacchae, though the women have already left the city, Pentheus singles out the female population of his city for special attention (215–32, 260–63). As McNamara (2010, 180) notes, the switch in focus contributes to Ovid’s re-characterization of Pentheus and introduces a whiff of tragic irony: ‘Pentheus’ disregard of the female members of his audience parallels his argument … which urges the men to reject femininity in favour of masculinity. He dismisses women at his peril, of course; it is at their hands that he will meet his death (3.708–31)’.

Additional Information: To understand the extent of the civic crisis created by Pentheus’ rift with his fellow Thebans, we must bear in mind that the human world described by Ovid at this point (and found in ancient myth more broadly) consisted of independent city-states, such as Thebes, whose members were bound by shared laws and religious practices. Individual religious activity and differentiated belief were less significant than they are today: it was primarily collectively, as a socio-political unit, that members of city-states interacted with the divine sphere, with leading figures often ‘performing’ the interaction through collective ritual acts. Hence a major rift between a ruler and the broader citizen body in this domain would constitute a grievous problem — none more grave.

531–32 Quis … mentes? As an interrogative quis is usually substantival, but is sometimes found as a m. adjective, as here and again at 632 (quis clamor?). So quis modifies furor (on which more below), the subject of the sentence (cf. 3.641). The verb attonuit is present perfect (‘has thunderstruck’ your minds) rather than simple past (‘did thunderstrike’): the inhabitants are in the thrall of Bacchic possession while Pentheus attempts to reason with them. quis furor is a question that, as Hardie (1990, 225) points out, Pentheus ‘might with more propriety address to himself’ (cf. 577–78 with n.). The dramatic query has an epic antecedent at Virg. Aen. 5.670, where the young prince Ascanius addresses the flipped-out Trojan women who are trying to set fire to their own fleet with quis furor iste novus? (‘What strange madness is this?’).

References to madness or insanity recur throughout the Pentheus episode, as here with furor (again at 641). Other signifiers belonging to the semantic field of madness include amens (628), demens (641), furor/ furens (623, 716), and insania/ insanus (536, 670, 711). The various attributions, however, show that madness is in the eyes of the beholder: the terms are applied indiscriminately by Pentheus to describe the conduct of the Maenads (as here), and by the narrator to describe Pentheus. The same is true of the inset tale that follows: the crew accuses Acoetes of madness (641–42), Acoetes the crew. This split reality poses a challenge for readers: we have to make up our own minds as to which of these attributions to accept. Ovid uses additional means to suggest that a given individual is out of his or her mind. In Pentheus’ case, he highlights the fact that the Theban king is in thrall to violent emotions, in particular anger (ira: 577, 693, 707; rabies: 567). In terms of genre, furor originally belongs to the world of tragedy — there is no equivalent to the ‘constitutional insanity’ so characteristic of the tragic stage in the Homeric epics (though Homeric heroes are of course emotionally incontinent, especially when their honour is at stake, and do ‘lose it’ at times). From 5th-century Athenian tragedy, the phenomenon or theme of ‘madness’ migrated into epic, not least Aeneid 4, which features the tragedy of Dido deranged.

The two vocatives belong to lofty epic diction: anguigenae is a compound adjective (a composite of anguis, ‘snake’ and -gena, ‘born from’) and proles Mavortia a poetic formula (520 n.). Taken together they make for a highly evocative address to the citizenry, and one that recalls its legendary origins. The compound anguigenae refers back to the dragon of Mars that dwelled at the site of the future city, and speaks to the birth of the Thebans from the serpent’s teeth (513–14 n.); an equally appropriate compound is terrigenae, ‘earth-born’ (a composite of terra, ‘earth’ and -gena, ‘born from’), which Ovid uses at 3.118, when he recounts the birth of the Spartoi. As for proles Mavortia, it should probably be taken as roughly synonymous with anguigenae (‘the offspring of [the dragon of] Mars’), particularly as earlier accounts have Mars sire the dragon: Ovid would then be alluding to such traditions in the manner of a doctus poeta (‘learned poet’). An alternative might be to understand a reference to the fact that Cadmus, the founder of Thebes, married Harmonia, the daughter of Mars and Venus (Met. 3.132–33). For a Roman reader, such references to ‘Martian’ lineage would call to mind other founding figures who descended from Mars (and, not unlike the Spartoi, also perpetrated fratricide in the course of laying the foundation of a new city): the twins Romulus and Remus, with the former founding Rome after slaying the latter. According to hoary legend, their sire was Mars, who impregnated the Vestal Virgin Ilia. If it is hard to repress Roman analogies here, it will soon become well-nigh impossible (538–40 n.).

532–37 aerane … vincant? Pentheus here launches into a long rhetorical question to rally his Thebans. The main verb is valent, which takes three subjects: aera (in the participial phrase aere repulsa), tibia (with the further specification adunco … cornu), and fraudes (qualified by the adjective magicae). Then follows a consecutive ut-clause (set up by tantum). Its main verb is vincant; it takes four subjects: voces (qualified by the adjective femineae), insania (which comes with the participle phrase mota … vino), greges (qualified by the adjective obsceni), and tympana (qualified by the adjective inania). The accusative object of vincant is an implied vos, which functions as the antecedent of the relative pronoun quos. The verb of the relative clause is terruerit; it takes three subjects: ensis (qualified by the adjective bellicus), tuba, and agmina (with the further specification strictis … telis).

For Pentheus, the situation is tantamount to an invasion, and his language sets conventional terminology of warfare, in which he reckons his Thebans to excel, against the perverse and effeminate (from his point of view) Bacchic incursion:

|

Regular warfare |

Bacchants |

|

|

Weaponry |

bellicus ensis, |

magicae fraudes, |

|

Musical instruments |

tuba |

aera, tibia, tympana, femineae voces |

|

Military Formation |

agmina |

obsceni greges |

Pentheus insists that the martial vigour of his compatriots (expressed with the resounding triple *anaphora of non in 534–35) ought to dispatch the effeminate and unwarlike Bacchic ‘invaders’. By his obsessive military logic, ensis and tela ought easily to rout magicae fraudes and insania, the tuba should easily drown out the cacophonous racket produced by Bacchic instruments (on which more below) and female shrieking, and a properly drawn-up army (agmina) ought to make short shrift of a disorganized effeminate hord (obsceni greges).

532–34 aerane … ut. The adverb tantum goes with valent and sets up the ut-clause: ‘Are x, y, and z so powerful that …’

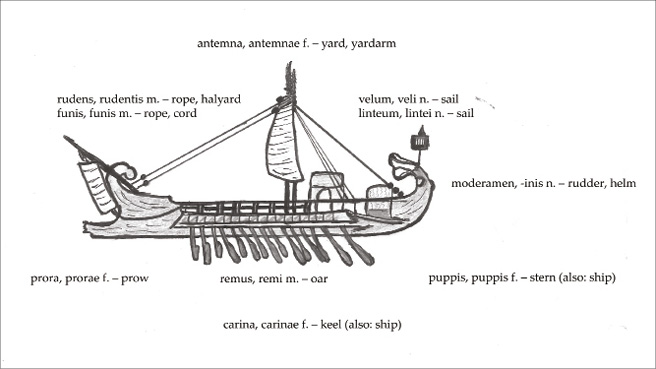

The formulation aerane … aere repulsa is very similar to Lucr. 2.636 pulsarent aeribus aera (‘they clashed bronze upon bronze’), which may have been Ovid’s inspiration (if this isn’t Ennius’ epic resounding through both of them). Here, as often, aes (‘copper or bronze’) is used by metonymy for ‘a musical instrument made of bronze’ (cf. 586 calamus, 621 pinus with nn.). Since aera is nom. pl. and aere abl. sing., we have ‘bronze (instruments) struck by bronze (instruments)’. The instruments in question (fig. 5) are cymbals, which were used in the worship of Bacchus, along with the Phrygian flute (tibia, also mentioned here) and kettledrum (tympanum, mentioned at 537). The participle repulsa (‘beaten back’) neatly captures the action of the cymbals clashing. The *polyptoton, the enjambment, and the ‘echo’ in ae-re re-pulsa help to join in the rhythmic beat of the percussion.

Fig. 5 Musical instruments.

The musical instrument indicated by adunco tibia cornu is the so-called Phrygian (or Berecynthian) flute, used in the cult of Bacchus/ Dionysus as well as that of the goddess Cybele. adunco … cornu is ablative of description, a frequent construction in Ovid (we see it again at 607): the tibia was a straight wind instrument that ended in an upwards-bending horn (which magnified the sound produced).

Literally rendered, magicae fraudes would yield ‘magical frauds’, but since fraudes cancels out the claim to supernatural power implied by magicae, a better rendering might be ‘charlatanry’. Pentheus regards any pretension to efficacious magic on the part of Bacchus as fraudulent — hardly surprising given his conviction that the latter is an impostor. The charge recalls a passage in Euripides’ Bacchae, where Pentheus comments scornfully on reports that a ‘wizard conjurer’ (γόης ἐπωιδὸς, 234) has arrived from Lydia. The Greek formulation is slightly more ambiguous since it leaves open the possibility that the alleged wizardry is genuine — an ambiguity reinforced by the equivocal focalization (the people whose report Pentheus is reporting most likely believe in the supernatural powers of the stranger, whereas Pentheus clearly does not). Charlatanry was no doubt a common charge levelled against various mystery cults in historical times (as Livy’s account of followers of Bacchus in early 2nd century BCE Italy illustrates: see Intro. §6). The sense of secrecy and, of course, mystery with which these cults shrouded their rites naturally suggested the idea of magic to outside observers.

534–35 quos … telis. In the middle of the long rhetorical question we get, buried in a relative clause, an evocation of the martial spirit of the Thebans, the overpowering of which by Bacchus is the immediate cause of Pentheus’ dismay. Ovid plays with the assonance of t (tuba — terruerit — strictis — telis), to recreate the sound of the tuba. This device is in the tradition of Ennius’ Annals, where it was used to more extravagant effect: at tuba terribili sonitu taratantara dixit (‘and the trumpet in terrible tones blared “taratantara”’, Ann. 140 Sk); Africa terribili tremit horrida terra tumultu (‘Africa, a rough land, trembled with a terrible tumult’, Ann. 310 Sk).

Note the progression from equipment (ensis) to the signal to attack (tuba) to the actual onslaught of the enemy in rank and file (agmina) with weapons drawn (strictis … telis). Pentheus here seems to refer to an occasion in which the Thebans faced an enemy army in regular battle without fear. It is difficult to match this occasion with any event in Thebes’ very young history: ancient myth records no such encounter, and Cadmus’ battle with the dragon or the civil war among the Spartoi (the military scenarios that defined the foundation of the city) do not fit the bill. terruerit is perfect subjunctive, an instance of ‘subjunctive by attraction’ arising from the fact that the relative clause containing terruerit is dependent on the subjunctive vincant in 537. Relative clauses that depend upon subjunctives and constitute an integral part of the thought will themselves take the subjunctive (AG §593).

536–37 femineae … vincant? Despite the fact that Pentheus blames Bacchus for upsetting the strict separation of male and female, the dominant group participating in Bacchic rites are women. As he makes clear later in his speech (esp. 553–56), Pentheus regards Bacchus as deficient in masculinity: the emphatic use of femineae calls into question the virility of any man in his entourage.

We might translate mota insania vino as ‘wine-induced madness’. The participle mota has the sense ‘occasioned’ or ‘excited’ (OLD s.v. moveo, 16). Bacchus, god of the vine, was of course well known for inducing states of inebriation and ecstasy in his worshippers; Pentheus acknowledges the phenomenon, but deprives it of any religious significance by characterizing it as what we might now term ‘substance abuse’. In his view, Bacchus’ followers are intoxicated miscreants who conceal their sozzled antics under a veneer of ritual piety.

Pentheus’ contempt is clearly expressed in obsceni… greges: the word grex, like English ‘herd’ is often disparaging when used of human beings. The original sense of obscenus seems to have been ‘ill omened’ (so Ovid has obscena puppis at Her. 5.119, of the ship that conveyed Helen to Troy), whence it came to mean ‘detestable, repulsive’, and eventually something like ‘obscene’ in the modern sense. Sexual license and like transgressions were widely attributed to Bacchic cult practice (see e.g. Eur. Bacch. 215–23; Liv. 39.8.7 stupra promiscua, ‘widespread adultery’ with Intro. §6).

The tympanum is a kettledrum (fig. 5), basically a hollow circular frame with parchment stretched over it, held in one hand and struck with the other. The mention of this instrument, for which inanis (‘hollow’) is clearly an appropriate epithet (but perhaps a double entendre), completes the list of musical instruments associated with the cult (532–33 n.). As McNamara (2010, 179) observes, Pentheus ‘begins and ends his list with the actual musical paraphernalia of Bacchic worship (aera … tibia … tympana), while he places the more abstract Bacchic associations (fraudes … femineae voces … insania … obscenique greges) between these. He thus “buries” his less tangible concerns within the brackets of these “real” items. For these concerns (magic, insanity, obscenity, femininity) are the standard accusations levelled at Dionysiac/ Bacchic rites by those who often represent more traditional authoritative religion’.

The force of vincant is — for the reader at any rate — metaphoric. The reference in context must be to religious conversion vel sim., but here and elsewhere the use of military language and martial imagery exemplifies Pentheus’ martial obsession. Rather more subtly, it could also involve mythographic play with an older version of the tale, predating Euripides’ Bacchae, in which Pentheus responds to the arrival of Dionysus by leading an army into the mountains, only to be defeated in battle by a troop of Maenads.

538–42 vosne … decebat? The main verb is mirer, a deliberative subjunctive (‘should I not wonder at … ?’) taking a matched pair of accusative objects in *anaphora: vosne (538) and vosne (540). The interrogative particles -ne … -ne are attached to the words Pentheus wishes to emphasize: the two occurrences of vos. Taken literally, Pentheus is pondering which of the two age groups he should marvel at; but, as the alternatives are clearly not mutually exclusive, it is best to understand an implicit adverb such as magis: ‘should I be [more] bewildered at you … or at you?’ Note that each vos is followed by a vocative (senes; acrior aetas, o iuvenes, propriorque meae) and a relative clause (qui … posuistis, sinitis …; quos … decebat).

538–40 vosne … capi? The first group Pentheus singles out from the citizen body is that of the older men who arrived with Cadmus from Tyre (Ovid may have had his eye on Pentheus’ address to Cadmus and Tiresias at Eur. Bacch. 248–54: see 531–63 n.). This group cannot have been very large — in fact, it comes as something of a surprise that, excepting Cadmus, it exists at all. At the opening of Book 3, Ovid gave the impression that all of Cadmus’ companions were killed (3.46–59), before he went on to found an entirely autochthonous community by means of the dragon’s teeth. For the same reason, they are difficult to include among the anguigenae or a proles Mavortia that Pentheus addresses at the outset of his speech. These inconsistencies begin to make sense if we see them as a deliberate attempt on Ovid’s part to align the founding of Thebes with the founding of Rome, which also has a discrepant ‘double origin’: arrivals from elsewhere (Aeneas and his fellow Trojan refugees) and a founding hero descending from Mars (Romulus). Reminiscences of the Aeneid reinforce the parallel: (i) longa per aequora vecti: thematically Aen. 1.3 multum ille et terris iactatus et alto; lexically 1.375–76 diversa per aequora vectos, 1.379 (cited below); (ii) profugos … penates: Aen. 1.2 fato profugus; 1.68 (cited below); 1.378–79 sum pius Aeneas, raptos qui ex hoste penates | classe veho mecum; 3.86–88; penatibus et magnis dis; (iii) Tyron … posuistis: the notion of translatio imperii.

The verses are rhetorically wrought: there is the emotional gemination hac … hac (both modifying sede), further reinforced by *hyperbaton; the powerful *alliteration profugos posuistis … penates; along with some subsidiary alliterative touches (vosne … vecti; sinitis sine).

The participial phrase longa per aequora vecti is a variant on Cat. 101.1 multa per aequora vectus. The past participle vecti agrees with qui; Cadmus’ original companions, initially forming a search party, had sailed with him from Phoenicia (513–14 n.); but as just noted, none of these should still be alive at this point.

With hac Tyron, hac profugos posuistis sede penates, Ovid evokes in particular Virgil’s description of Aeneas at Aen. 1.68 Ilium in Italiam portans victosque penates (‘bringing Ilium and his defeated household gods to Italy’), where Ilium is an alternate name for his native Troy. Tyre (Latin Tyrus; Tyron is the accusative form) was a city of Phoenicia, the original homeland of Cadmus and his followers. Pentheus’ meaning is that they have in this location founded a ‘new Tyre’ (i.e. Thebes). The penates were, properly speaking, the guardian deities of a Roman household, closely associated with Vesta, goddess of the hearth, and worshipped in the home; there was a corresponding cult of public penates as well. Note that profugos (much like victos in Aen. 1.68) is a transferred epithet: it is not the penates who were exiled (or defeated) but their human wards. All in all, Pentheus’ statement is decidedly odd: not only are penates a Roman rather than Greek religious notion, but there would have been little reason for Cadmus and his followers to bring their penates (in the form of statues, which stood in the penetralia, or central point of a Roman home) with them because they originally left Phoenicia to search for Europa, not to found a new homeland (for the ‘backstory’ to this episode, see Intro. §5). Ovid has clearly worked against the grain, then, to have his mythical founding of Thebes evoke that of Rome. Speaking more broadly, it is worth noting that elements of Roman culture show up in the strangest places in the Metamorphoses: early in Book 1, for example, Ovid rather audaciously ascribes penates or household gods to the domiciles of the Olympian gods (1.173–74) — one of his strategies for insinuating the Roman telos of his poem in the early stages of his narrative (see Intro. §3d, and, for Ovid’s ‘triangulation’ of Thebes-Troy-Rome, Intro. §5 n. 46).

The (accusative) subjects of capi are Tyron and penates. Pentheus laments not merely the fact of capitulation, but that it comes sine Marte — without a violent struggle. Here, as often, Mars stands by metonymy for ‘war’, ‘battle’. This particular form of metonymy, in which a god stands for an activity or item with which he or she is associated (e.g. Bacchus = ‘wine’; Ceres = ‘bread’) is also known as denominatio.

540–42 vosne … decebat? The main verb continues to be mirer (538). Pentheus now turns to the younger generation of Theban men, and ratchets up the rhetorical effects. In poetry the interjection o (again in the set text at 579, 613, 641 and 713) inserted before a vocative — as here with iuvenes — creates a loftier form of address than the vocative by itself. The term iuvenis is a rather vague indicator of age, and one to which the English expression ‘young man’ does not exactly correspond. Roman thought generally divided a man’s life into four stages (ranges are approximate): infantia (0–2 years), pueritia (3–16), iuventus (17–45), senectus (46 +). Hence iuvenes can be thought of as designating men of fighting age. Both acrior and proprior (which takes a dative) contrast the younger men with the elderly; the former term (here in the comparative form) means something akin to ‘(more) warlike’. As acrior aetas stands in apposition to vos and o iuvenes, it must be abstract-for-concrete, a figure whereby a quality is abstracted from the concrete form in which it exists (similarly 617 tutela with n.). In English this can be rendered with the genitive: ‘young men of a more warlike age’. With meae supply aetati (a form of *ellipse common in Latin and English). With this fleeting personal aside, Pentheus bears out that he has come to the throne at a young age, but Ovid provides no further indications of his age (beyond what can be surmised from the mention that his grandfather Cadmus is still alive, and the fact that his mother and aunts are still sufficiently vigorous to tear him limb from limb with their bare hands). Euripides seems to make him a young man of about 20, or perhaps a bit less (see Bacch. 974, 1185–87, 1254).

The relative pronoun quos (whose antecedent is iuvenes) functions both as accusative object of decebat and subject accusative of the indirect statement introduced by it (with tenere and tegi as infinitives; they are linked by the -que after galea and by alliteration). This construction can be retained in English translation: ‘whom it used to befit to …’ (note the reproachful force of the imperfect tense: ‘it used to befit …’). The indirect statement combines parallelism with variation: we get two antitheses along the pattern: alternative 1 (arma + galea) — verb (tenere + tegi) — negation (non + non) — alternative 2 (thyrsos + fronde). But the first is active (tenere) with accusative objects (arma, thyrsos), the second passive (tegi) with instrumental ablatives (galea, fronde).

A thyrsus (fig. 6) is a wand twined with ivy and/ or vine branches (both plants were sacred to Bacchus) carried by the god, as well as by his followers during the god’s rites. It was one of the most recognizable accoutrements of Bacchus and his cult. Along with carrying the thyrsus, the god and his worshippers would crown their heads (whence tegi, a pres. pass. infinitive) with wreaths of ivy leaves, or a combination of vine and ivy leaves (whence fronde, a ‘collective’ singular) during the god’s rites. Bacchus himself is later described as ‘wreathed with clustering grapes’ (666–67 with n.).

Fig. 6 A thyrsus (‘A staff tipped by a pine cone’).

543–48 este … decus. Pentheus continues to address the younger generation(s) — those, who, like himself, are descendants of the dragon’s teeth. He begins with an elaborate reminder of their serpentine ancestry (543–45); the overall design of the verses is chiastic: (a) imperative (este … memores) + (b) relative clause (qua … creati) ‹› (b) relative clause (qui … unus) + (a) imperative (sumite). Then he draws two contrasts to underscore the triviality of dealing with Bacchus by comparison with the high stakes faced by the serpent and the heroic feats required of it:

|

Serpent |

Thebans |

|

|

Contrast 1 |

pro fontibus ille lacuque |

at vos pro fama vincite vestra |

|

Contrast 2 |

ille dedit leto fortes |

vos pellite molles |

Again *alliteration (in particular of ‘s’: sitis, stirpe, sumite, serpentis — reinforced by the endings in the same letter of memores, illius, animos, multos, unus, serpentis) generates formal coherence. McNamara (2010, 181) detects in the highly sibilant diction an evocation of the heroic serpent. Pentheus holds up the primordial monster as a civic role model for the Thebans to emulate. The appreciation of the monster that on its own (unus) slaughtered many (multos) companions of Cadmus illustrates Pentheus’ mindset: he values martial prowess and merciless butchery wherever and however they manifest themselves. Why does he not praise Cadmus? The killer of the serpent is still alive — indeed, he is present (564–65 n.). See Hardie (1990, 225 and 229–30) discussing the comparison with Rome, James (1991, 87–89), Feldherr (1997, 50).

543. The plea precor is ‘parenthetical’ and so does not affect the syntax of the clause, which is a command (este is 2nd pers. pl. pres. imperative of sum): ‘Be mindful!’ Note the interlaced word order of the indirect question (more regular would be qua stirpe creati sitis). The compound verb form sitis … creati is in the subjunctive (2nd pers. pl. perf. pass.) because of the indirect question, which is introduced by the interrogative adjective qua, modifying stirpe, an ablative of origin. Phaethon uses a like formulation at 1.760 si modo sum caelesti stirpe creatus (‘if I am indeed born of heavenly stock …’).

544–45 illiusque … serpentis! The -que after illius links the imperatives este and sumite. illius modifies serpentis in a striking instance of *hyperbaton: the ‘framing’ genitive encloses the noun on which it depends (i.e. animos, the object of the clause), the relative clause for which it is the antecedent, and the main verb (sumite).

Variations on the theme of one against many (multos perdidit unus) recur throughout the set text, starting with Pentheus opposing the Bacchus-worship of the citizens of Thebes (513 ex omnibus unus with n.). Here the contrast between multos and unus subtly prepares the isolated position Pentheus finds himself in at the end of his speech.

545–48 pro fontibus … decus! After appealing to the Theban citizens’ serpentine genealogy, Pentheus develops an elegant *antithesis, reinforced by *anaphora, contrasting the heroics of the dragon (ille … ille, also picking up illius … serpentis) with the lesser feats he asks of the Theban men (at vos … vos). The -que after lacu links fontibus and lacu. For lower stakes (pro fontibus … lacuque vs. pro fama vestra), the dragon undertook a more daunting task: he killed brave men (ille dedit leto fortes), whereas the Thebans merely have to drive away weaklings (vos pellite molles). Moreover, the dragon perished in defence of his realm (interiit), whereas the Thebans can expect to emerge victorious (vincite) and unscathed. Pentheus ends the sentence with an appeal to ancestral honour: patrium retinete decus. This is, as it were, Pentheus’ variation on Horace’s well-known line dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (‘sweet and honourable it is to die for one’s country’, Carm. 3.2.13): the ancestral dragon died in defence of his realm, a point made emphatic by enjambment of the crucial verb interiit and the trithemimeral *caesura that follows it.

The declaration ille dedit leto fortes has an elevated, epic ring arising partly from the use of letum, an archaic and poetic synonym for mors (‘death’), and partly from the periphrastic formulation itself (‘gave over to death’ rather than simply ‘killed’). With fortes supply viros (referring to Cadmus’ companions): this is the direct object of dedit; leto is the indirect object. The account of the serpent’s slaughter of Cadmus’ companions was narrated earlier at 3.46–49.