Untitled Page 09

- Page ID

- 114951

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

We really value your participation, please take part!

© Ingo Gildenhard and Andrew Zissos, CC BY 4.0 http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0073.01

Ovid, or (to give him his full Roman name) Publius Ovidius Naso, was born in 43 BCE to a prominent equestrian family in Sulmo (modern Sulmona), a small town about 140 km east of Rome. He died in banishment, a resident of Tomi on the Black Sea, in 17 CE. Ovid was one of the most prolific authors of his day, as well as one of the most controversial.1 He had always been constitutionally unable to write anything in prose — or so he claims in his autobiography (composed, of course, in verse). Whatever flowed from his pen was in metre, even after his father had told him to put an end to such nonsense:

saepe pater dixit ‘studium quid inutile temptas?

Maeonides2 nullas ipse reliquit opes’.

motus eram dictis, totoque Helicone3 relicto

scribere temptabam verba soluta modis.

sponte sua carmen numeros veniebat ad aptos,

et quod temptabam dicere versus erat.

(Trist. 4.10.21–26)

My father often said, ‘Why try a useless

Vocation? Even Homer left no wealth’.

So I obeyed, all Helicon abandoned,

And tried to write in prose that did not scan.

But poetry in metre came unbidden,

And what I tried to write in verses ran.

(tr. Melville)

Students of Latin may well be familiar with Naso senior’s banausic attitude: classics graduates, some wrongly assume, have similarly dismal career prospects. But eventually Ovid would shrug off paternal disapproval in pursuit of his passion. After dutifully filling certain minor offices, he chose not to go on to the quaestorship, thereby definitively renouncing all ambition for a senatorial career. In his case, the outcome was an oeuvre for the ages. For quick orientation, here is a time-line with the basics:4

|

Time-line |

Historical Events |

Ovid’s Biography |

Literary History |

|

50s BCE |

Catullus, Lucretius |

||

|

44 |

Julius Caesar murdered |

||

|

43 |

Cicero murdered |

Ovid born |

|

|

30s |

[Gallus Amores 1–4 (lost)], |

||

|

35 |

Virgil Eclogues |

||

|

31 |

Battle of Actium |

||

|

29 |

Virgil Georgics |

||

|

27 |

Octavian becomes ‘Augustus’ |

||

|

Time-line |

Historical Events |

Ovid’s Biography |

Literary History |

|

Early 20s |

Livy 1–10 |

||

|

20s |

Propertius 1–3, Tibullus 1, |

||

|

19 |

Virgil Aeneid, Tibullus 1–2 |

||

|

18 |

Leges Iuliae (initial Augustan marriage legislation) |

||

|

17 |

Secular Games; |

Horace |

|

|

16 |

Propertius 4 |

||

|

10s–0s |

Amores 1–3, Heroides, Medicamina faciei femineae, Medea |

Horace Ars Poetica, Epistles 2, Odes 4 |

|

|

2 BCE |

Ars Amatoria 1–2 |

||

|

1 CE |

Birth of Jesus |

||

|

2 |

Ars Amatoria 3 |

||

|

4 |

Augustus adopts Tiberius |

||

|

8 |

Scandal at court; Augustus relegates Ovid to Tomi on the Black Sea |

Finished just before the relegation (?): Metamorphoses 1–15, Fasti 1–6 |

|

|

8–17 |

Tristia 1–5, Epistulae ex Ponto 1–4, Ibis, Double Heroides |

||

|

14 |

Augustus dies; |

||

|

10s |

Manilius Astronomica |

||

|

17 (?) |

Ovid dies |

Livy dies |

Ovid was born when the Republic, the oligarchic system of government that had ruled Rome for centuries, was in its death throes. He was a teenager at the time of the Battle of Actium, the final showdown between Mark Antony and Octavian that saw the latter emerge victorious, become the first princeps, and eventually take the honorific title ‘Augustus’ by which he is better known to posterity. Unlike other major poets of the so-called ‘Augustan Age’ — Virgil, Horace, Propertius, Tibullus — Ovid never experienced a fully functional form of republican government, the libera res publica in whose cause figures like Cato and even Cicero ultimately died. There is another important difference between Ovid and most of the other major Augustan poets: he did not have a ‘patron-friend’, such as Maecenas (a close adviser of the princeps who, in the 30s, ‘befriended’ Virgil, Horace and Propertius) or Messalla, the amateur poet and power-politician to whom Tibullus dedicates his poetry. Ovid came from a prominent family and was financially self-sufficient: this left him free — or so he must have thought — to let rip his insouciant imagination.

A consummate urbanite, Ovid enjoyed himself and was an immensely popular figure in the fashionable society of Augustan Rome. He was more than happy to endorse the myth that the founding hero Aeneas and thus the city itself had Venus in their DNA (just spell Roma backwards!). For him Rome was first and foremost the city of Love and Sex and his (early) verse reads like an ancient version of ‘Sex and the City’.

Eventually, though, Ovid ran afoul of the regime. In 8 CE, when he was fifty years old, Ovid was implicated in a lurid court scandal that also involved Augustus’ niece Julia and was relegated by the emperor to Tomi, a town on the Black Sea (the sea-port Constanța in present-day Romania).5 The reasons, so Ovid himself tells us, were a ‘poem and a mistake’ (‘carmen et error’, Trist. 2.207). He goes on to identify the poem as the Ars Amatoria — which had, however, been published a full ten years earlier — but declines to elaborate on the ‘mistake’, on the grounds that it would be too painful for Augustus. He maintained this reticent pose for the rest of his life, so what the error was is now anybody’s guess (and many have been made). In any event, despite Ovid’s pleas the hoped-for recall never came, even after the death of Augustus, and he was forced to pine away the rest of his life far from his beloved Rome. He characterizes Tomi as a primitive and dreary town, located in the middle of nowhere, even though archaeological evidence suggests that it was a pleasant seaside resort. And while his poetry continued to flow, it did so in a very different vein from the light-hearted exuberance that characterizes his earlier ‘Roman’ output; the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto explore the potential of the elegiac distich (a verse-form consisting of a six-foot hexameter and a five-foot pentameter in alternation: the metre of mourning as well as love) to articulate grief. But on his career trajectory from eros to exile, Ovid made forays into non-elegiac genres: tragedy (his lost play Medea) and, of course, epic. In the following section we will explore Ovid’s playful encoding, in a range of texts, of his longstanding epic ambition and its final realization in the Metamorphoses.

2. Ovid’s Literary Progression: Elegy to Epic

When the first edition of the Metamorphoses hit the shelves in the bookshops of Rome, Ovid had already made a name for himself in the literary circles of the city.6 His official debut, the Amores (‘Love Affairs’) lured his tickled readers into a freewheeling world of elegiac love, slaphappy hedonism, and (more or less) adept adultery.7 His subsequent Heroides (‘Letters written by Heroines to their absent Hero-Lovers’) were also designed to appeal to connoisseurs of elegiac poetry, who could here share vicariously in stirring emotional turmoil with abandoned women of history and myth: Ovid, well attuned to female plight, provided the traditional heroes’ other (better?) halves with a literary forum for voicing feelings of loss and deprivation and expressing resentment for the epic way of life. Of more practical application for the Roman lady of the world were his verses on toiletry, the Medicamina Faciei (‘Ointments of the Face, or, How to Apply Make-up’). Once Ovid had discovered his talent for didactic exposition, he blithely continued in that vein. In perusing the urbane and sophisticated lessons on love which the self-proclaimed erotodidaskalos (‘teacher of love’) presented in his Ars Amatoria (‘A — Z of Love’) his male (and female) audience could hone their own amatory skills, while at the same time experiencing true ‘jouissance’ (the French term for orgasmic bliss, for the sophisticates among you) in the act of reading a work, which is, as one critic put it, ‘a poem about poetry, and sex, and poetry as sex’.8

After these extensive sessions in poetic philandering, Ovid’s ancient readers, by then all hopeless and desperate eros-addicts, surely welcomed the thoughtful antidote he offers in the form of the therapeutic Remedia Amoris (‘Cures for Love’), a poem written with the expressed purpose of freeing the wretched lover from the baneful shackles of Cupid. To cut a long story short: by the time the Metamorphoses were published, Ovid’s devotees had had ample opportunity to revel in the variety of his literary output about the workings of Eros, and each time, the so-called elegiac distich provided the metrical form. Publius Ovidius Naso had become, apart from a brief flirtation with the genre of tragedy (the lost Medea, written in Latin iambic trimeters), a virtual synonym for the composition of erotic-elegiac verse. But picking up and un-scrolling any one of the fifteen books that contained the Metamorphoses, a reader familiar with Ovid’s literary career is in for a shock. Here are the first four lines of the work, which make up its proem:

In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas

corpora; di, coeptis (nam vos mutastis et illa)

adspirate meis primaque ab origine mundi

ad mea perpetuum deducite tempora carmen.

(Met. 1.1–4)

My mind compels me to sing of shapes changed into new bodies: gods, on my endeavours (for you have changed them too) breathe your inspiration, and from the very beginning of the world to my own times bring down this continuous song.

A mere glance at the layout (no indentations in alternate lines!) suffices to confirm that Ovid has definitively changed poetic metiers (as the ‘change’ of verse between formas and corpora makes a ‘new’ syntactical role for the opening phrase In nova).9 In his newest work the foreshortened pentameters, which until now had been a defining characteristic of his poetry, have disappeared. Instead, row upon steady row of sturdy and well-proportioned hexameters confront the incredulous reader. Ovid, the celebrated master of the distich, the notorious tenerorum lusor amorum (‘the playboy of light-hearted love-poetry’ as he calls himself), the unrivalled champion of erotic-elegiac poetry, has produced a work written in ‘heroic verse’ — as the epic metre is portentously called.

But once the initial shock has worn off, readers familiar with Ovid’s earlier output are bound to experience a sense of déjà vu (as the French say of what they have seen before). Ovid, while devoting his previous career to versifying things erotic, had always shown an inclination towards epic poetry. Already in the introductory elegy to the first book of the Amores, the neophyte announced that he was writing elegies merely by default. His true ambition lay elsewhere; he had actually meant to write an epic:

Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam

edere, materia conveniente modis.

par erat inferior versus — risisse Cupido

dicitur atque unum surripuisse pedem.

(Am. 1.1.1–4)

About arms and violent wars I was getting ready to compose in the weighty hexameter. The material matched the metrical form: the second verse was of equal length to the first — but Cupid (they say) smiled and snatched away one of the feet.10

As can be gathered from pointed allusions to the Aeneid (which begins Arma virumque cano: ‘I sing of arms and the man’) at the opening, the poem Ovid set out to write before Cupid intervened would have been no routine piece of work, but rather an epic of such martial grandeur as to challenge Virgil’s masterpiece. Ovid’s choice of the hexameter for the Metamorphoses signals that he has finally realized his long-standing ambition to compose an epic. But already the witty features of the proem (starting with its minuscule length: four meagre lines for a work of fifteen books!) indicate that his embrace of the genre is to be distinctly double-edged. And, indeed, his take on epic is as unconventional as his efforts in elegiac and didactic poetry had been. Just as the Amores spoofed the more serious output of his elegiac predecessors Propertius and Tibullus and his string of didactic works (the Ars Amatoria, the Remedia Amoris, the Medicamina Faciei) spoofed more serious ventures in the genre such as Virgil’s Georgics (a poem on farming), so the Metamorphoses has mischievous fun with, while at the same time also outperforming, the Greco-Roman epic tradition from Homer to Virgil. It is arguably the most unusual epic to have come down to us from antiquity — as well as one of the most influential.

3. The Metamorphoses: A Literary Monstrum

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid parades a truly dazzling array of mythological and (as the epic progresses) historical matter before his audience. Aristotelian principles of narrative unity and ‘classical’ plotting have clearly fallen by the wayside. In breathtaking succession, the fast-paced narrative takes his readers from the initial creation myths to the gardens of Pomona, from the wilful intrusion of Amor into his epic narrative in the Apollo and Daphne episode to the ill-starred marriage feast of Pirithous and Hippodame (ending in an all out brawl, mass-slaughter, and a ‘Romeo and Juliet’ scene between two centaurs), from the Argonauts’ voyage to Colchis to Orpheus’ underworld descent (to win back his beloved Eurydice from the realms of the dead), from the charming rustic couple Philemon and Baucis to the philosopher Pythagoras expounding on nature and history, from the creative destruction of Greek cultural centres such as Thebes in the early books to the rise of Rome and the apotheosis of the Caesars at the end. As Ovid proceeds through this remarkable assortment of material, the reader traverses the entire cosmos, from the top of Mount Olympus where Jupiter presides over the council of the gods to the pits of Tartarus where the dreadful Furies hold sway, from far East where, at dawn, Sol mounts his fiery chariot to far West where his son Phaethon, struck by Jupiter’s thunderbolt, plunges headlong into the Eridanus river. Within the capacious geographical boundaries of his fictional world, Ovid’s narrative focus switches rapidly from the divine elegiac lover Apollo to the resolute virgin Diana, from the blasphemer Lycaon to the boar slaying Meleager, from the polymorphic sexual exploits of Pater Omnipotens to the counterattacks of his vengeful wife Juno. At one point the poet flaunts blameless Philomela’s severed tongue waggling disconcertingly on the ground, at another he recounts the dismemberment of the Thessalian tyrant Pelias at the hands of his devoted daughters. On a first encounter the centrifugal diversity of the narrative material which Ovid presents in his carmen perpetuum (‘continuous song’) is bound to have a disorienting, even unsettling effect on the reader. How is anyone to come to critical terms with the astonishing variety of narrative configurations that Ovid displays in this ever-shifting poetic kaleidoscope?11

The hexametric form, the cosmic scope and the sheer scale of the Metamorphoses all attest to its epic affiliations. As just discussed, the poem’s opening verses seem to affirm that Ovid realized his longstanding aspiration to match himself against Virgil in the most lofty of poetic genres. But as soon as one scratches the surface, myriad difficulties emerge. Even if we choose to assign the Metamorphoses to the category of epic poetry, idiosyncrasies abound. A tabular comparison with other well-known instances of the genre brings out a few of its fundamental oddities:

|

Author |

Title |

Length |

Main Theme |

Protagonist |

|

Homer |

Iliad |

24 Books |

Wrath and War |

Achilles |

|

Homer |

Odyssey |

24 Books |

Return/Civil War |

Odysseus |

|

Apollonius Rhodius |

Argonautica |

4 Books |

Travel and Adventure |

Jason |

|

Ennius |

Annals |

15/18 Books |

Men and their deeds |

Roman nobles |

|

Virgil |

Aeneid |

12 Books |

Arms and the Man |

Aeneas |

|

Ovid |

Metamorphoses |

15 Books |

Transformation |

? |

The tally of fifteen books, while deviating from the ‘multiple-of-four-or-six’ principle canonized by Homer, Apollonius Rhodius, and Virgil, at least has a precedent in Ennius’ Annals.12 But Ovid’s main theme and his choice of protagonist are decidedly peculiar (as will be discussed in the following sections). And then there is the playfulness of the narrative, its pervasive reflexivity, and its often arch or insouciant tone — elements largely absent from earlier instantiations of the genre. ‘The Metamorphoses is perhaps Ovid’s most innovative work, an epic on a majestic scale that refuses to take epic seriously’.13 Indeed, the heated and ultimately inconclusive debate that has flared up around the question of whether the Metamorphoses is an epic, an eroticization of epic, a parody of epic, a conglomeration of genres granted equal rights, an epic sui generis or simply a poem sui generis might seem to indicate that Ovid has achieved a total breakdown of generic conventions, voiding the validity of generic analysis altogether. Karl Galinsky once cautioned that ‘it would be misguided to pin the label of any genre on the Metamorphoses’.14 But does Ovid, in this poem, really dance outside genre altogether? Recent scholarship on the Metamorphoses suggests that the answer is ‘no’. Stephen Hinds articulates the issue at stake very well; in reconsidering the classic distinction between Ovidian epic and elegy, he remarks that

… in the opening lines [of the Metamorphoses], the epic criterion is immediately established as relevant, even if only as a point of reference for generic conflict … Boundaries are crossed and recrossed as in no poem before. Elements characteristic of elegy, bucolic, didactic, tragedy, comedy and oratory mingle with elements variously characteristic of the grand epic tradition and with each other … However, wherever its shifts may take it, the metre, bulk and scope of the poem ensures that the question implied in that opening paradox will never be completely eclipsed: namely in what sense is the Metamorphoses an epic?15

In other words, denying the Metamorphoses the status of epic (or at least epic aspiration) means depriving the text of one of its most intriguing constitutive tensions. Ovid needs the seriousness, the ideology and the reputation of epic as medium for his frivolous poetics, as the ultimate sublime for his exercise in generic deconstruction and as the conceptual matrix for the savvy of his metageneric artistry (i.e. artistry that self-consciously, if often implicitly, reflects on generic matters). Within this epic undertaking, most other genres find their place as well — not least in the set text where elements of epic, oratory, hymnic poetry, tragedy, and bucolic all register (and intermingle).

Scholars are again divided on how best to handle the multiplicity of generic voices that Ovid has included in the Metamorphoses. Are we perhaps dealing with ‘epic pastiche’? One critic answers in the affirmative: ‘For my purposes … the long poem in hexameters is a pastiche epic whose formal qualities are shaped by an invented genre that is at once ad hoc and sui generis, one with no real ancestors but with many and various offspring’.16 But another objects that ‘it is a mistake often made to identify one section of the Metamorphoses as “elegiac”, another as “epic”, another as “comic”, another as “tragic”, as if Ovid put together a pastiche of genres. Actually, elements of all these genres, and others as well, are as likely as not to appear together in any given story’.17 Arguably a more promising way to think critically about the generic presences in Ovid’s poem is to see the genres in dialogue with one another in ways that are mutually enriching.18 All genres have their own distinctive emphasis and outlook, and to have several of them at work at the same time challenges us, the readers, to negotiate sudden changes in register and perspective, keeping us on our toes.

3b. A Collection of Metamorphic Tales

Its hexametric form aside, the most striking formal feature of the Metamorphoses is that, as its title announces, it strings together a vast number of more or less distinct tales, each of which features a metamorphosis — that is, a magical or supernatural transformation of some kind. In composing a poem of this type, Ovid was working within a tradition of metamorphic literature that had blossomed a few centuries earlier in Hellenistic culture. In terms of his apparent generic aspirations, Ovid’s main theme (and hence his title) is unequivocally — and shockingly — unorthodox: before him, ‘transformative change’ was a subject principally cultivated in Hellenistic catalogue poetry, which is about as un-epic in scope and conception as literature can get.19

Nicander’s Heteroeumena (‘Changed Ones’), datable to the 2nd century BCE, is the earliest work dedicated to metamorphosis for which we have reliable attestations. The surviving fragments are scant, but valuable testimony is preserved in a prose compendium written by Antoninus Liberalis. The Heteroeumena was a poem in four or five books, written in dactylic hexameters, which narrated episodes of metamorphosis from disparate myths and legends, brought together in a single collection. An overarching concern was evidently to link tales of metamorphosis to the origin of local landmarks, religious rites or other cultural practices: Nicander’s stories were thus predominantly aetiological in orientation, very much like Callimachus’ Aetia. At the close of the Hellenistic period, Greek metamorphosis poetry evidently found its way to Rome, along with its authors. So, for example, Parthenius, the Greek tutor to Virgil, who came to Rome in 65 BCE, composed a Metamorphoses in elegiacs, about which we unfortunately know next to nothing.

Considered against this literary backdrop, Ovid’s initial announcement in the Metamorphoses that this would be a poem about ‘forms changed into different bodies’ (in nova … mutatas formas | corpora, 1.1–2) might well have suggested to a contemporary reader that Ovid was inscribing himself within a tradition of metamorphosis poetry tout court — setting himself up, that is, as the Roman exemplar of the sub-genre of Hellenistic metamorphosis catalogue poetry represented by such works as Nicander’s Heteroeumena. But Ovid’s epic was vastly more ambitious in conception, and proved to be no less revolutionary in design. Nicander’s Heteroeumena and other ‘collective’ metamorphosis poems from the Hellenistic period are characterized by a discontinuous narrative structure: each included tale constitutes a discrete entry, sufficient unto itself, so that the individual stories do not add up to an organic whole. Ovid’s Metamorphoses marks a radical departure from these predecessors: while each individual tale sports the qualities we associate with the refined and sophisticated, as well as small-scale and discontinuous, that Callimachus and other Hellenistic poets valued and cultivated, the whole is much more than the sum of its parts.

What distinguishes the Metamorphoses from these precursors is that it is chronologically and thematically continuous. In strictly formal terms, it is this chronological framework that constitutes Ovid’s innovation within the tradition of ancient catalogue poetry. He marshals into a continuous epic narrative a vast assortment of tales of transformation, beginning with the creation of the cosmos and ending in his own times. Every ‘episode’ within this narrative thus needs to satisfy two conditions: (i) it must follow on from the preceding episode in some kind of temporal succession; (ii) it must contain a metamorphosis. The second condition is sometimes met by resort to ingenious devices. The set text is a case in point: the story of Pentheus, as inherited from Euripides and others, did not contain an ‘orthodox’ instance of metamorphosis, i.e. of a human being transforming into flora, fauna, or an inanimate object (though of course it does feature the changeling god Bacchus in human disguise and hallucinating maenads who look at Pentheus only to see a wild animal). To make good this deficiency, Ovid includes an inset narrative told by the character Acoetes, who delivers, as a cautionary tale for Pentheus, a long-winded account of how Bacchus once transformed a group of wicked Etruscan pirates into dolphins. Now some readers, particularly those coming to Ovid from the earlier tradition of metamorphic catalogue poetry, might regard this as ‘cheating’; others, however, might appreciate the ingenuity with which Ovid explores the limits and possibilities of metamorphosis, combining orthodox instances of transformative change with related phenomena, such as divine allophanies (‘appearances in disguise’) or hallucinations (‘transformations in the eyes of a beholder, based on misperception of reality that is nevertheless frightfully real in its consequences’). What is at any rate remarkable is that such ‘tricks’ as Acoetes’ inset narrative are comparatively rare: on the whole, the Metamorphoses meets the daunting, seemingly impossible, challenge of fashioning, in the traditional epic manner, an ‘unbroken song’ (perpetuum … carmen, 1.4) from disparate tales of transformation.

Ovid’s epic is a work of breathtaking ambition: it gives us nothing less than a comprehensive vision of the world — both in terms of nature and culture (and how they interlock). The Metamorphoses opens with a cosmogony and offers a cosmology: built into the poem is an explanation (highly idiosyncratic, to be sure) of how our physical universe works, with special emphasis on its various metamorphic qualities and possibilities. And it is set up as a universal history that traces time from the moment of creation to the Augustan age — or, indeed, beyond. In his proem Ovid promises a poem of cosmic scale, ranging from the very beginning of the universe (prima ab origine mundi) down to his own times (ad mea tempora).20 He embarks upon an epic narrative that begins with the creation of the cosmos and ends with the apotheosis of Julius Caesar. The poet’s teleological commitment to a notional ‘present’ (the Augustan age in which the epic was composed) qua narrative terminus is subtly reinforced by frequent appeals to the contemporary reader’s observational experience. The result is a cumulatively compelling sequence that postures, more or less convincingly, as a chronicle of the cosmos in all its pertinent facets.

Taken in its totality, Ovid’s epic elevates the phenomenon of metamorphosis from its prior status as a mythographic curiosity to an indispensable mechanism of cosmic history, a fundamental causal element in the evolution of the universe and the story of humanity: the Metamorphoses offers not a mere concatenation of marvellous transformations, but a poetic vision of the world conceived of as fundamentally and pervasively metamorphic.

The claim that the Metamorphoses amounts to a universal history may well sound counterintuitive, and for two reasons in particular. First, chronology sometimes seems to go awry — not least through the heavy use of embedded narrative — so that the audience is bound to have difficulty keeping track of the trajectory that proceeds from elemental chaos at the outset to the Rome of Augustus at the end. But upon inspection, it turns out that Ovid has sprinkled important clues into his narrative that keep the final destination of his narrative in the minds of (attentive) readers.21 The second puzzle raised by the historical orientation of Ovid’s epic concerns its principal subject matter: instances of transformative change that are clearly fictional. Ovid himself concedes as much. In one of his earlier love elegies, Amores 3.12, he laments the fact that, owing to the success of his poetry, his girlfriend Corinna has become the toast of Rome’s would-be Don Giovannis. Displeased with the prospect of romantic competition, he admonishes would-be rivals to read his love elegies with the same incredulity they routinely bring to bear on mythic fabulae — and proceeds to belabour the point in what almost amounts to a blueprint of the Metamorphoses (Am. 3.12.19–44). Ovid’s catalogue of unbelievable tales includes Scylla, Medusa, Perseus and Pegasus, gigantomachy, Circe’s magical transformation of Odysseus’ companions, Cerberus, Phaethon, Tantalus, the transformations of Niobe and Callisto, Procne, Philomela, and Itys, the self-transformations of Jupiter prior to raping Leda, Danaë, and Europa, Proteus, and the Spartoi that rose from the teeth of the dragon slain by Cadmus at the future site of Thebes. The catalogue culminates in the punchline that just as no one really believes in the historical authenticity of such tales, so too readers should be disinclined to take anything he says about Corinna at face value:22

Exit in inmensum fecunda licentia vatum,

obligat historica nec sua verba fide.

et mea debuerat falso laudata videri

femina; credulitas nunc mihi vestra nocet.

(Am. 3.12.41–43)

The creative licence of the poets knows no limits, and does not constrain its words with historical faithfulness. My girl ought to have seemed falsely praised; I am undone by your credulity.

The same attitude towards tales of transformative change informs his retrospect on the Metamorphoses at Trist. 2.63–64, where Ovid adduces the implausibility of the stories contained within his epic: Inspice maius opus, quod adhuc sine fine tenetur, | in non credendos corpora uersa modos (‘Look at the greater work, which is as of yet unfinished, bodies transformed in ways not to be believed’). As one scholar has observed, ‘a critic could hardly wish for a more explicit denial of the reality of the myth-world of the Metamorphoses’.23

In light of how Ovid presents the theme of metamorphosis elsewhere (including moments of auto-exegesis, where he tells his own story), it comes as no surprise that ‘the Metamorphoses’ challenges to our belief in its fictions are relentless, for Ovid continually confronts us with such reminders of his work’s fictional status’.24 But this feature of his text is merely the result of his decision to write fiction as history. Put differently, what is so striking about his project is not that Ovid is writing self-conscious fiction. Rather, it is his paradoxical insistence that his fictions are historical facts. From the start, Ovid draws attention to, and confronts, the issue of credibility. A representative instance comes from his account of how Deucalion and Pyrrha replenish the earth’s human population after its near extermination in the flood by throwing stones over their shoulders:

saxa (quis hoc credat, nisi sit pro teste vetustas?)

ponere duritiem coepere …

(Met. 1.400–01)

The stones (who would believe this if the age of the tale did not function as witness?) began to lose their hardness …

In his parenthetical remark Ovid turns vetustas (‘old age’) into a criterion for veritas (‘truth’), slyly counting on, while at the same time subverting, the Roman investment in tradition, as seen most strikingly in the importance afforded to exempla and mores maiorum (that is, ‘instances of exemplary conduct and ancestral customs’). His cheeky challenge to see fictions as facts (and the ensuing question of belief) accompanies Ovid’s characters (and his readers) throughout the poem, including the set text, where Pentheus refuses to believe the cautionary tale of Bacchus’ transformation of the Tyrrhenian pirates into dolphins — with fatal consequences.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that some of the narrative material is historical. The reader must remain ever alert to the programmatic opening declaration that the Metamorphoses will proceed chronologically from the birth of the universe to the poet’s own times (Met. 1.3–4, cited and discussed above). Ovid is, in other words, combining myth and history, with the latter coming to the fore in the final books, which document the rise of Rome. The end of the Metamorphoses celebrates the ascendancy of Rome to world-empire: terra sub Augusto est (‘the world lies under Augustus’, 15.860) observes Ovid laconically of the comprehensive sway of Roman rule in his own day (15.876–77). This is presented as a culminating moment in world history.

The combination of myth and history was, of course, hardly new. The Hebrew Bible, to name just one precedent, began in the mythological realm with Genesis, proceeded to the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve, the deluge, and so on before moving on to more overtly historical material. And whereas this was long considered (and in some quarters still is considered) a historical document throughout, Ovid, as we have seen, is more willing to probe the implausibility of the traditional mythological tales that he has placed side-by-side with historical material. But readers of the Metamorphoses should be wary of placing too much stock in the dichotomy of myth and history. From an ideological perspective, the real issue is less the truth-value of specific events narrated in the epic, than the way they make sense of — and shape perceptions of — the world. The subtle anticipations of Roman geopolitical domination in Ovid’s early books are scarcely less significant for being embedded in Greek mythology. A case in point arises in the opening book, where Jupiter summons all the gods in assembly in reaction to perceived human depravity, as epitomized in the barbarous conduct of Lycaon. Here, it would appear, Ovid puts on display his generic bona fides: any ancient epic worthy of the name could hardly omit a concilium deorum. From Homer onwards an assembly of the gods had been an almost compulsory ingredient of the genre.25 But for all the seeming conventionality of his set-up, Ovid provides a decidedly eccentric rendition of the type-scene. The oddities begin with a striking account of the summoned divinities hastening along the Milky Way to the royal abode of Jupiter:

Est via sublimis, caelo manifesta sereno;

lactea nomen habet, candore notabilis ipso.

hac iter est superis ad magni tecta Tonantis

regalemque domum: dextra laevaque deorum

atria nobilium valvis celebrantur apertis.

plebs habitat diversa loca: hac parte potentes

caelicolae clarique suos posuere penates;

hic locus est, quem, si verbis audacia detur,

haud timeam magni dixisse Palatia caeli.

(Met. 1.168–76)

There is a highway, easily seen when the sky is clear. It is called the Milky Way, famed for its shining whiteness. By this way the gods come to the halls and royal dwelling of the mighty Thunderer. On either side the palaces of the gods of higher rank are thronged with guests through folding-doors flung wide. The lesser gods dwell apart from these. In this neighbourhood the illustrious and mighty heaven-dwellers have placed their household gods. This is the place which, if I made bold to say it, I would not fear to call the Palatine of high heaven.

In these lines, Ovid describes a celestial Rome. Jupiter’s abode, the palace of the great ruler, is situated on a heavenly Palatine; the Milky Way is like the Sacer Clivus which led from the Via Sacra to the Palatine Hill in Rome, where of course Augustus lived. As with the Romans, the gods are divided into nobles and plebeians; the former have magnificent and well-situated abodes, complete with atria teeming with clientes; the latter must make do with more humble and obscure quarters. More strikingly, celestial patricians and plebs alike have their penates (household gods).26 And the analogies don’t end there. The assembly that meets in Jupiter’s palace follows procedures that are recognizably those of the Roman Senate.27 Indeed, ‘the correspondence with Augustan Rome is particularly close at this point, since we know that Augustus held Senate meetings in the library attached to his temple of Apollo on the Palatine, which was itself intricately linked with his residence’.28

The comical audacity of this sequence has elicited reams of commentary. Since Homer, the traditional epic practice was to model divine existence on human analogy, but to attribute household gods (penates) to the Olympian gods themselves is humorously to extend and expose the convention.29 At the same time, though, Ovid achieves a more profound effect, for the episode hints at a kind of politico-historical telos: the Olympian political structures and those of contemporary Rome are in homology. For all the humorous touches — and we certainly do not wish to deny them — Ovid has inscribed Augustan Rome into the heavens. Since Jupiter’s rule is to be eternal, there is an implication, by association, of a corresponding political-historical closure in human affairs. From the very beginning, then, the disconcerting thematic implications of potentially endless metamorphosis — which Pythagoras will assert as axiomatic for geopolitical affairs — are being countered or ‘contained’ with respect to Roma aeterna. Heaven has stabilized — the final challenges to the Jovian cosmos, those of giants and their like, are now ‘in the books’ — and will suffer no further political upheavals of significance. An equivalent state of affairs is subsequently to be achieved on the terrestrial level. The human realm will, over the course of Ovid’s narrative, evolve into the Jovian paradigm — which is already, by the comic solipsism just discussed, the Roman paradigm. The majestic declaration in the final book terra sub Augusto est (15.860) neatly signals that the princeps has achieved the Jovian analogy; this is the language of divine power, which is to say, the earth being ‘beneath’ Augustus makes both his power and figurative vantage point god-like.30

In writing a universal history, its eccentric narrative voice and hexametric form notwithstanding, Ovid is performing a peculiarly Roman operation. For some scholars, indeed, history first became universal in Roman times; on this view it was the creation of the Roman Empire that allowed history to become ‘global’ in a geographical sense.31 This version of history adopted more or less consciously an ethnocentric or ‘Romanocentric’ perspective that freely incorporated mythical elements in explaining Roman supremacy in terms of both surpassing virtus (making the Romans superior imperialists) and surpassing pietas (guaranteeing them the privileged support of the gods).

Together, the record of supernatural powers and transformed human beings that the Metamorphoses chronicles adds up to a unique combination of ‘natural’ and ‘universal’ history, in which cosmos and culture evolve together and eventually (in the form of a Roman civilization that has acquired global reach under Augustus) coincide.

To use the theme of metamorphosis as the basis for a universal history did not just strain, it shattered prevailing generic norms. From Homer to Virgil, the stuff of epic was war and adventure, heroes and their deeds; in Ovid, it is — a fictitious phenomenon.32 A related curiosity arises over the question of protagonist. In the other epics of our tabular comparison (see above, §3a), it is a simple matter to identify the main character or characters.33 That is decidedly not the case in the Metamorphoses: Ovid’s frequently un-heroic personnel changes from one episode to the next, to the point that some scholars have suggested that the hero of the poem is the poet himself — the master-narrator who holds (and thinks) everything together and, in so doing, performs a deed worthy of immortality.34 There is, to be sure, much to be gained from focusing on the ‘composition myth’ in this way, but it does not rule out pinpointing a protagonist on the level of plot as well. As Ernst Schmidt has argued, a plausible candidate for this designation is ‘the human being’.35

There are some difficulties with this suggestion (one might well ask: what about the gods?); but all in all the thesis that humanity as such takes centre-stage in the Metamorphoses is attractive and compelling. At its core, the poem offers a sustained meditation on what it is to be human within a broader cosmic setting shaped by supernatural agents and explores the potential of our species for good and for evil. These concerns (one could label them ‘anthropological’) are set up by the various forms of anthropogenesis (‘accounts of the origins of humanity’) in the early episodes, which trace our beginnings to such diverse material as earth and a divine spark, stones cast by mortal hands, and the blood of slain giants. From an ethical point of view, the outcomes are as diverse as the material: Ovid explores a wide gamut of possibilities, covering the full range from quasi-divine and ethically impeccable human beings (witness the blissful rectitude of the golden age at 1.83–112) to bestial and blasphemous (the version of our species that descended from the blood of giants, described at 1.156–62). In the Deucalion and Pyrrha story (a ‘pagan’ variant on the tale of Noah’s ark), Ovid makes the aetiological connection between the kind of material from which humanity is manufactured and our respective qualities explicit: originating from stones, ‘we are hence a hard race, experienced in toil, and so giving testimony to the source of our birth’ (inde genus durum sumus experiensque laborum | et documenta damus, qua simus origine nati, 1.414–15). As the reader proceeds through the poem, encounters with such atrocious human beings as Tereus or such admirable individuals as Baucis and Philemon serve as vivid reminders that accursed and salvific elements are equally part of our DNA. A ‘rhetoric of origins’ also plays an important role in the set text: Pentheus tries to rally the citizens of Thebes against Bacchus and his entourage by reminding them of their descent from the teeth of the dragon of Mars (3.543–45) — a belated anthropogenesis on a local scale that re-enacts the opening theme at a later stage of cosmic history.

In line with both Ovid’s elegiac past and his ‘anthropological’ interest in humanity, the Metamorphoses is chock-full of sex and gender issues — though readers will have to venture beyond the set text to discover this: the chosen episode is relatively free from erotic entanglements. In fact, Ovid has in many ways ‘de-eroticized’ earlier versions of the Pentheus-myth, such as the one we find in Euripides’ Bacchae, which features cross-dressing, prurient interest in orgiastic sexuality, and voyeurism. But browse around a bit before or after the set text and you’ll see that Ovid never departs for long from erotic subject matter. You’ll find that, as discussed below (§5b-i), the sober figure of the blind seer Tiresias who introduces the Pentheus-episode first features in the poem as a divinely certified ‘sexpert’ on male and female orgasms. More generally, sex and gender are such pervasive preoccupations that one scholar has plausibly characterized the Metamorphoses as a ‘hymn to Venus’.36

3e. A Reader’s Digest of Greek and Latin Literature

In the process of laying out a vast body of mythic tales, both well known and recondite, Ovid’s Metamorphoses produces something like a ‘reader’s digest’ of Greek and Latin literature. Whichever authors came before him — Homer, Euripides, Callimachus, Apollonius Rhodius, Theocritus, Ennius, Lucretius, Catullus, Virgil, you name them — he worked their texts into his own, often with a hilarious spin or a polemic edge. In Ovid, the literary heritage of Greece and Rome begins to swing. His poetics — his peculiar way of writing poetry — is as transformative as his choice of subject matter. In the Metamorphoses, one intertextual joke chases the next as Ovid puts his predecessors into place — turning them into inferior forerunners or footnotes to his own epic mischief. To appreciate this dimension of his poem requires knowledge of the earlier literature that Ovid engages with. In the set text, Ovid’s partners in dialogue include, but are by no means limited to, Homer, the author of the Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, Euripides, pseudo-Theocritus, Pacuvius (a 2nd-century BCE Roman tragic playwright whose work survives only in scant fragments), and Virgil. Even this partial enumeration, consisting as it does of authors and texts that have come down to us more or less intact as well as those that have all but vanished, points to an occupational hazard for anyone interested in literary dialogue: so much ancient literature that Ovid and his readers would have known intimately is lost to us. Literary critics (including the present writers: see below, §5a) will inevitably tend to stress the intertextual relationships between texts that have best survived the accidents of transmission (in our case: the Odyssey, Euripides’ Bacchae, the Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, the pseudo-Theocritean Idyll 26, and Virgil’s Aeneid). So it is worth recalling that, as far as, say, tragic plays about Bacchus and Pentheus are concerned, Ovid would have had at his disposal not only Euripides’ Bacchae, but a number of other scripts that are lost to us or have only survived in bits and pieces, notably Pacuvius’ Pentheus. This does not invalidate the exercise of comparing Euripides and Ovid — far from it. Even if it is salutary to bear in mind that we are almost certainly seeing only part of the full network of intertextual relationships, we should take solace from the fact that, as John Henderson points out, ‘plenty of ancient Roman readers were in the same boat as us: Ovid catered for all levels, from newcomers to classical studies to impossibly learned old-stagers. And the main point remains, that, just as verse form always brings change to a tale, so too a myth can never be told in anything but a new version — stories forever mutate’.

The ‘reader’s digest’ effect of the Metamorphoses works in tandem with its cosmic scope, totalizing chronology and encyclopaedic ambition to endow it with a unique sense of comprehensiveness. More fundamentally still, Ovid’s epic codified and preserved for evermore one of antiquity’s earliest and most important ways of making sense of the universe: myth. As a result, it has become one of the most influential classics of all time: instances of reception are legion, as countless works of art that engage with the mythic heritage of antiquity found their ultimate inspiration in Ovid’s poetry. The Metamorphoses has been called ‘the Bible of artists and painters’ and ‘one of the cornerstones of Western culture’.37 It is virtually impossible to walk into any museum of note without encountering artworks that rehearse Ovidian themes; and his influence on authors, not least those of the first rank — from Dante to Petrarch, from Shakespeare to Milton — is equally pervasive.38 ‘Bible’ and ‘cornerstone’, though, with their implications of ponderous gravity and paradigmatic authority, are rather odd metaphors to apply to Ovid’s epic: they capture its importance through the ages, but unwittingly invert why the Metamorphoses has continued to resonate with so many creative geniuses (as well as the average reader). After all, Ovid’s intense exploration of erotic experience in all its polymorphous diversity and his vigorous celebration of transformative fluidity (or, indeed, eternal flux) in both nature and culture make of the poem a veritable counter-Bible, offering a decidedly unorthodox vision of the universe and its inhabitants.

It is a fundamental principle of narration, as John Henderson reminds us, that ‘a tale tells on its teller — all these stories came into Ovid’s mind-and-repertoire, and these are his versions, so “about” Ovid’. And (he adds) ‘tales mean to have designs on those on the receiving-end, and now that includes us, and that means you. There are many reasons why the Metamorphoses (plural) keep bulldozing their way through world culture, but this (singular) is what counts the most. As Horace put it: de te fabula narratur’.39

While some themes can be encountered virtually anywhere in the Metamorphoses, others cluster in certain parts and generate a distinctive narrative ethos. The first two books, for instance, have attracted the label ‘Divine Comedy’: they feature various sexual adventures of the Olympian gods — mostly rapes of mortal women. All cry out for a feminist critique, even if — or, better, because — the narrative tone remains fairly light throughout. With the beginning of Book 3, Ovid’s literary universe takes on a darker complexion. The first protagonist of the book is the Phoenician prince Cadmus, whose appearance is a carry-over from the concluding rape/abduction tale of the previous book. At the behest of his father Agenor, Cadmus attempts to track down his sister Europa, whom Jupiter had carried off at the end of Book 2 — a veritable mission impossible. Unsuccessful in his search and forbidden by his father to return home empty-handed, Cadmus heads into voluntary exile. His wanderings bring him to Boeotia where he founds Thebes, a city in which tragic and ultimately hellish energies are unleashed.40

Considered from the perspective of the ancient literary tradition, it is hardly coincidental that Ovid’s epic takes a ‘tragic’ turn as it turns to Theban myth. For in Attic drama, as Froma Zeitlin has demonstrated in a seminal essay, ‘Thebes consistently supplies the radical tragic terrain where there can be no escape from the tragic in the resolution of conflict or in the institutional provision of a civic future beyond the world of the play’.41 The city indeed epitomizes what Greek tragedy is all about. Judging from the surviving scripts of Athenian playwrights, daily life in ancient Thebes featured incessant civil strife, repeated autochthonous disaster, miscellaneous forms of sexual perversion (rape, sodomy, incest), and even the occasional human dismemberment (sparagmos) — in short, the entire range of transgressions that upset the normal order of things. To quote Zeitlin again: ‘Thebes, we might say, is the quintessential “other scene”, as Oedipus is the paradigm of tragic man and Dionysus is the god of the theatre. There Athens acts out questions crucial to the polis, the self, the family, and society, but there they are displaced upon a city that is imagined as the mirror opposite of Athens’.42 Ovid’s version of Thebes fully lives up to the anticipation of calamity evoked by the city’s longstanding tragic associations. As the fates of Cadmus and Harmonia, Actaeon, Semele, Narcissus, Pentheus, and Ino and Athamas show, the myths that Ovid here incorporates into his epic world have lost none of the sinister and fateful character that they had acquired on the tragic stage. These dramatis personae embark once more on a literary destiny within a tragic dystopia that inexorably leads them to their doom.

There is, indeed, a striking coherence to Met. 3.1–4.603, the narrative stretch that begins with Cadmus’ exile and ends with his and his wife Harmonia’s transformation into snakes (stories concerning the city’s founder and his offspring are in italics):

|

3.1–137 |

Foundation: Cadmus, his companions, the dragon of Mars, the Spartoi |

|

|

3.138–252 |

Actaeon, son of Autonoe |

|

|

3.253–315 |

Semele (birth of Bacchus) |

|

|

3.316–38 |

Teiresias (and his sex-changes) |

|

|

3.339–510 |

Echo and Narcissus |

|

|

3.511–733 |

Pentheus, son of Agave (including the inset tale of Bacchus and the Tyrrhenian sailors) |

|

|

4.1–415 |

The daughters of Minyas and Bacchus |

|

|

4.55–388 |

Tales of the Minyeides: |

|

|

4.55–166 |

Pyramus and Thisbe |

|

|

4.169–270 |

The Love Affairs of the Sun |

|

|

4.276–388 |

Salmacis and Hermaphroditus |

|

|

4.416–562 |

Ino and Athamas with Learchus and Melicertes |

|

|

4.563–603 |

Cadmus & Harmonia: exile and transformation into snakes |

|

Met. 3.1–4.603 has been termed Ovid’s Thebaid, insofar as it is the city of Thebes (and its environs) that provides a unifying thematic and topographical focus. Even when the narrative veers off — as in the case of Tiresias, Echo and Narcissus, and the daughters of Minyas (the ‘Minyeides’) — Thebes remains an important point of reference. So, for example, the Minyeides, who reside in the near-by city of Orchomenos, while in many ways forming a self-contained narrative unit within Ovid’s Thebaid, are unable to escape the tragic forces that emanate from Thebes. Not unlike Pentheus, they fall victim to the powers of Bacchus, whom they unwisely choose to disregard.

Clearly, then, Thebaid is an appropriate label for Met. 3.1–4.603; no less appropriate, though, would be Cadmeid (‘an epic poem about Cadmus and his offspring’), inasmuch as Ovid chronicles the fates of Cadmus and Harmonia, along with their four daughters and five grandsons:

|

Cadmus and Harmonia |

||||

|

Daughters |

Autonoe |

Semele |

Agave |

Ino |

|

Grandsons |

Actaeon |

Bacchus |

Pentheus |

Learchus and Melicertes |

Twice Cadmus himself comes into focus: his heroics get the Theban narrative going at the beginning of Book 3; and his despairing exit from the city together with his wife and the transformation of the couple into snakes brings this particular narrative unit to a close. This ‘frame’ is worth a more detailed look since it defines the thematic terms for the episodes it encloses, including the set text.

The opening sequence treats events up to the foundation of the city: Cadmus’ arrival in Boeotia, the slaughter of his companions by the dragon of Mars, Cadmus’ revenge-killing of the beast, his sowing of its teeth at the behest of a divine voice, the rise of the Spartoi and their mutual slaughter, which leaves only a handful of survivors — Thebes’ citizen population.43 Ovid skips over the actual foundation (and the wedding of Cadmus and Harmonia), restricting himself to what amounts to a tragic prologue for the subsequent narrative:

Iam stabant Thebae, poteras iam, Cadme, videri

exilio felix: soceri tibi Marsque Venusque

contigerant; huc adde genus de coniuge tanta,

tot natos natasque et, pignora cara, nepotes,

hos quoque iam iuvenes; sed scilicet ultima semper

exspectanda dies hominis, dicique beatus

ante obitum nemo supremaque funera debet.

Prima nepos inter tot res tibi, Cadme, secundas

causa fuit luctus …

(Met. 3.131–39)

And now Thebes stood; now you could seem, Cadmus, a happy man even in exile. Mars and Venus had become your parents-in-law; add to this children of so distinguished a wife, so many sons and daughters and, pledges of your love, grandchildren, these too now at the brink of manhood. But of course man’s last day must ever be awaited and no-one ought to be called happy before his death and funeral rites. Among such favourable circumstances, Cadmus, the first cause of grief was one of your grandsons …

After recounting the wretched fates of Cadmus’ children and grandchildren, Ovid returns to the royal couple: his Theban history ends with Cadmus and Harmonia heading off into self-imposed exile and eventually transforming into snakes (Met. 4.563–603). Cadmus himself prays for this metamorphosis as he recalls how it all began, thus bringing the narrative full circle:

Nescit Agenorides natam parvumque nepotem

aequoris esse deos; luctu serieque malorum

victus et ostentis, quae plurima viderat, exit

conditor urbe sua, tamquam fortuna locorum,

non sua se premeret, longisque erroribus actus

contigit Illyricos profuga cum coniuge fines.

iamque malis annisque graves dum prima retractant

fata domus releguntque suos sermone labores,

‘num sacer ille mea traiectus cuspide serpens’

Cadmus ait ‘fuerat, tum cum Sidone profectus

vipereos sparsi per humum, nova semina, dentes?

quem si cura deum tam certa vindicat ira,

ipse precor serpens in longam porrigar alvum’.

dixit, et ut serpens in longam tenditur alvum.

(Met. 4.563–76)

Cadmus was unaware that his daughter (Ino) and little grandson (Melicertes) had been changed to gods of the sea. Overcome with grief and the sequence of calamities and because of the many portents he had seen, the founding father left his city, as if the fortune of the site rather than his own were oppressing him. Driven on through long wanderings, at last the exile and his wife reached the borders of Illyria. At that point, heavy with woes and years, while they went over the early calamities of their house and their own troubles in conversation, Cadmus said: ‘Was that a sacred serpent which my spear transfixed back when, recently departed from Sidon, I scattered his teeth, a novel type of seed, on to the earth? If the care of the gods is avenging him with such unerring wrath, I pray that I, too be stretched into snaky form as a serpent’. And as he spoke he was stretched into a snaky form as a serpent …

A nexus of verbal correspondences correlates the beginning and end of Ovid’s Cadmeid. At 3.131–42, Cadmus’ apparent good fortune is quantified via his abundant progeny: he might seem enviable, the poet portentously observes, in view of his numerous daughters (natas), sons (natos), and grandchildren (nepotes). This initial plurality contrasts sharply with the singulars of the phrase natam parvumque nepotem at 4.563. The words refer to Cadmus’ daughter Ino and grandson Melicertes, the only members of his family not yet visited by catastrophe — though Cadmus believes himself to have just witnessed their hellish destruction as well. For him they are the final link in the long chain of misfortunes which began with the gruesome demise of Actaeon (prima … causa fuit luctus, 3.138–39), continued through Book 3 (including Pentheus) and came to its bitter end with the lethal madness of Ino and her husband, recounted at 4.481–542. It is precisely this long sequence of dreadful calamities (luctu serieque malorum, 4.564) which drives Cadmus from the city that he himself founded (exit | conditor urbe sua, 4.565–66).

We thus start and end with Cadmus in exile; but the two exiles could hardly be more different. At the beginning of Book 3 Cadmus is in his prime, about to perform the deeds which brought him heroic renown, i.e. the killing of the dragon of Mars and the founding of Thebes. In Book 4, by contrast, we encounter a man broken down by age and suffering who is desperately trying to come to terms with the series of misfortunes that has plagued his family. Ovid underscores the bleak transformation of Cadmus from the active protagonist of Book 3 into the despairing and gloomy figure we meet in Book 4 through pointed verbal play. Most strikingly, in assuming the shape of his erstwhile victim Cadmus fulfils the prophecy uttered immediately after his triumphant slaying of Mars’ serpent:

Dum spatium victor victi considerat hostis,

vox subito audita est; neque erat cognoscere promptum,

unde, sed audita est: ‘quid, Agenore nate, peremptum

serpentem spectas? et tu spectabere serpens’.

(Met. 3.95–98)

While the victor surveys the size of his vanquished foe, suddenly a voice is heard; it was impossible to recognize from where, but it was heard: ‘Why, son of Agenor, do you gaze upon the serpent you killed? You too will be gazed upon as serpent’.

Through its startling prediction, the unattributed voice implicitly proclaims the dreadful law that in a tragic universe each source of good fortune contains the seeds of its own undoing. Like the serpent in this early scene, at 4.565 Cadmus is described as defeated (victus). In the later passage, moreover, Cadmus has, through bitter experience, come to understand the typically Theban proximity of victory and disaster at which Ovid already signalled, both overtly through the prophecy of Cadmus’ ultimate transformation into the very shape of his conquered enemy, and more subtly through the collocation of victor and victi at 3.95. Cadmus’ final realization that he killed a sacred beast closes down Ovid’s Theban narrative by returning it to the point at which it all began. In a traumatic reversal, the very objects that once promised a prosperous future for Thebes, the teeth of the dragon — compare 3.103 vipereos dentes, populi incrementa futuri with 4.571–73, where Cadmus ponders the possibility that the vipereos dentes he used come from a sacred beast — in hindsight turn out to bear within them the burden of a curse that was bound to blight developments from the outset. Cadmus’ wish to be transformed into a serpent arises from the painful realization that only a metamorphic ‘return’ to the origin of his city will put an end to his agony: it is a culminating illustration of the fact that Thebes is ever unable to differentiate itself from its troubled beginnings.44

In the course of the narrative arch that Ovid traces in his Theban history, we thus get a tragic conflation of human and beast and an equally tragic inversion of victor (‘conqueror’) and victus (‘conquered’) as Cadmus rises from a condition of exile to become king of his own city, and progenitor of a prosperous family, before being reduced again to his original status as a childless outcast. Yet the transformation of Cadmus into a snake might also elicit the cleansing laughter of a Satyr play after a day of tragic performances.45 In this respect also it might be seen as a fitting Ovidian conclusion to the Theban saga. As Cadmus’ wish to assume the shape of a dragon is incrementally realized, his horrified wife bemoans his vanishing human features and, more importantly, the unbearable zoomorphic divide that now sunders the couple (Met. 4.576–94). No sooner said than remedied: she promptly undergoes the same metamorphosis and joins her husband on the ground. While at the end of Euripides’ Bacchae, the prophetic anticipation of Cadmus’ transformation into a dragon sets up new horrors since he is to lead a foreign army against the Greeks (Bacch. 1330–43), Ovid’s snakified Cadmus and Harmonia are truly peaceful creatures (cf. 4.602–03). In the Metamorphoses at least, the tragic energy of Thebes is spent.46

5. The Set Text: Pentheus and Bacchus

It will be clear from our discussion so far that the Pentheus episode lies at the heart of Ovid’s Theban narrative in a number of important respects. The setting for this episode is the city of Thebes, which, as we have seen, was founded by Cadmus, after his search for his abducted sister Europa proved fruitless.47 Cadmus is now an old man, and has abdicated the throne of his city in favour of his grandson Pentheus. Early in the reign of the young king, a new religious cult sweeps in from the East, that of the god Bacchus (Greek Dionysus), son of the god Jupiter and the Theban princess Semele (their explosive affair and Bacchus’ unusual birth were described earlier in Book 3, at 253–315). While nearly all Thebans welcome the new cult, Pentheus is obstinate in his scepticism and resistance, an attitude that leads to his doom.

The story of Pentheus and Bacchus was well established long before Ovid’s day. The myth was a popular subject with writers and artists alike, and is famously the subject of the Bacchae, a tragedy by the 5th-century BCE Athenian playwright Euripides. This tragedy was, as far as we can tell, Ovid’s most important source and model.48

Euripides begins his play with Bacchus’ arrival at Thebes and a detailed exposition of his world, carefully elaborated in the prologue (1–63, spoken by the god himself) and the chorus upon their entry onto the stage (64–169, sung by Lydian women). The enthusiastic celebration of the Maenads in particular introduces the entire range of imagery and motifs commonly associated with Bacchic frenzy, highlighting notions of excess and boundary transgression.49 In the subsequent scenes, Euripides proceeds to delineate the character of Pentheus, who flatly denies Bacchus’ divinity and rejects his worship, and so resents all the more the enthusiastic reception of the god and his cult by the Theban populace. Euripides places particular emphasis on the Theban king’s obsession with the sexual license he associates with the worship of Bacchus.50 The story continues with Pentheus giving orders to his henchmen to capture Bacchus, who is presently brought on stage (Bacch. 432–42). In the initial interview Bacchus conceals his true identity, claiming merely to be one of the followers of the new deity, and he remains incognito until his final epiphany. His exchanges with Pentheus culminate in the key scene in which the god convinces Pentheus to cross-dress as a woman so he can spy on the Maenads on Mount Cithaeron — a grave offense given that their rites were both secret and an exclusively female matter. This leads to the grim denouement, in which Bacchus distorts the perception of Pentheus’ mother Agave and her sisters, as well as the other Maenads, so that they misrecognize the disguised king as a wild beast which, in accordance with Bacchic rites, they proceed to tear limb from limb with their bare hands. Euripides’ gruesome and haunting account of Pentheus’ dismemberment comes in the form of a messenger’s speech:

‘Then were a thousand hands laid on the fir tree [sc. in which Pentheus was perched], and from the ground they tore it up, while he from his seat aloft came tumbling to the ground with lamentations long and loud; for well he knew his hour was come. His mother first, a priestess for the occasion, began the bloody deed and fell upon him; whereon he tore the snood from his hair, that hapless Agave might recognize and spare him, crying as he touched her cheek, “O mother! it is I, your own son Pentheus, the child you bore in Echion’s halls; have pity on me, mother dear! oh! do not for any sin of mine slay your own son”. But she, the while, with foaming mouth and wildly rolling eyes, bereft of reason as she was, heeded him not; for the god possessed her. And she caught his left hand in her grip, and planting her foot upon her victim’s trunk she tore the shoulder from its socket, not of her own strength, but the god made it an easy task to her hands; and Ino set to work upon the other side, rending the flesh with Autonoe and all the eager host of Bacchanals; and one united cry arose, the victim’s groans while yet he breathed, and their triumphant shouts. One would make an arm her prey, another a foot with the sandal on it; and his ribs were stripped of flesh by their rending nails; and each one with blood-dabbled hands was tossing Pentheus’ limbs about. Scattered lies his corpse, part beneath the rugged rocks, and part amid the deep dark woods, no easy task to find; but his mother has made his poor head her own, and fixing it upon the point of a thyrsus, as if it were a mountain lion’s, she bears it through the midst of Cithaeron, having left her sisters with the Maenads at their rites. And she is entering these walls exulting in her hunting fraught with woe, acclaiming Bacchus her fellow-hunter who had helped her to triumph in a chase, where her only prize was tears’.

(Eur. Bacch. 1109–47)

This is the ‘classic’ account of Pentheus’ demise, but here as elsewhere, Ovid is in literary dialogue with multiple predecessors. In certain respects his version of the horrific event bears closer resemblance to that of a poem included (probably wrongly) in the Theocritean corpus as Idyll 26. This deals with the initiation of a young boy into the mysteries of Dionysus, with the father giving the following account of Pentheus’ death and dismemberment:

[1] Ino, Autonoe and white-cheeked Agave, themselves three in number, led three groups of worshippers to the mountain. Some of them cut wild greenery from the densely growing oak trees, living ivy and asphodel that grows above ground, and made up twelve altars in a pure meadow, three to Semele and nine to Dionysus. Taking from their box the sacred objects made with care, they laid them reverently on the altars of freshly gathered foliage, just as Dionysus himself had taught them, and just as he preferred.

[10] Pentheus observed everything from a high rock, hidden in a mastic bush, a plant that grew in those parts. Autonoe, the first to see him, gave a dreadful yell and with a sudden movement kicked over the sacred objects of frenzied Bacchus, which the profane may not see. She became frenzied herself, and at once the others too became frenzied. Pentheus fled in terror and they pursued him, hitching up their robes into their belts, knee-high. Pentheus spoke: ‘What do you want, women?’ Autonoe spoke: ‘You will know soon enough, and before we tell you’. The mother gave a roar like a lioness with cubs as she carried off her son’s head; Ino tore off his great shoulder, shoulder-blade and all, by setting her foot on his stomach; and Autonoe set to work in the same way. The other women butchered what was left and returned to Thebes all smeared with blood, bearing back from the mountain not Pentheus (Πενθῆα), but lamentation (πένθημα).

[27] This is no concern of mine, nor should anyone else care about an enemy of Dionysus, even if he suffered a worse fate than this, even if he were nine years old, or just embarking on his teeth. May I myself act piously, and may my actions please the pious. The eagle gained honour in this way from Zeus who bears the aegis. It is to children of the pious, not to those of the impious, that good things come.

[35] Farewell to mighty Dionysus, for whom on snowy Dracanus mighty Zeus opened up his own great thigh and placed him inside. Farewell, too, to beautiful Semele and her sisters, daughters of Cadmus, much admired by women of that time, who carried out this deed impelled by Dionysus, so that they are not to be blamed. Let no one criticize the actions of the gods.

([Theoc.] Id. 26)

All three texts share the same basic plot; but there are noteworthy variations on the level of detail. In Euripides and Ovid, for instance, Pentheus spies upon the maenads from a tree; in the Theocritean Idyll, by contrast, he is poised on a prominent rock. And whereas in Euripides Agave initiates the slaughter, in the Idyll and Ovid it is Agave’s sister (and Pentheus’ aunt) Autonoe. If Ovid conforms closely to Euripides’ tragedy in narrative outline, then, there are clearly departures that look to other texts or versions.

Ovid’s most striking innovation vis-à-vis Euripides has to do with the captive arrested by Pentheus’ henchmen. This figure has a precedent in the Bacchae, but he is never explicitly identified as Bacchus-in-disguise, as he is in the earlier text. Indeed, he gives his name as Acoetes and provides a comparatively detailed autobiography that begins by describing his rise from the lowly profession of fisherman to that of helmsman (more on this in the following section). More crucially still, in explaining how he became a follower of the god, he tells the tale of how a group of wicked Tyrrhenian sailors, his erstwhile shipmates, were transformed into dolphins by Bacchus. This inset tale conveniently supplies the episode with the requisite metamorphosis (which was lacking in the narrative Ovid inherited from Euripides). It also constitutes a radical — and, it should be added, ingenious — departure from the tragic model.

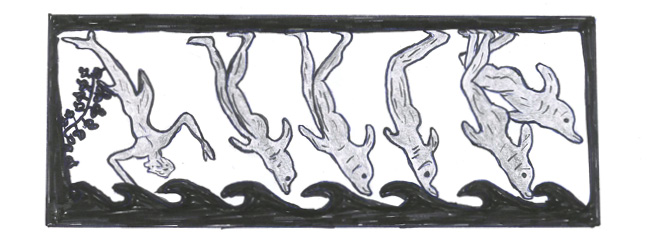

Fig. 1 The Tyrrhenian Pirates change into dolphins (drawing after a black-figure vase, 6th/5th century BCE, Museum of Art, Toledo).

The inset narrative is, in essence, an extended version of a Homeric Hymn to Dionysus.51 More specifically, it is a rendition of the longest of three hymns honouring Dionysus in a collection of some thirty such compositions, all anonymous, known as the Homeric Hymns. These Greek hexametric hymns vary in length from a handful of verses to several hundred lines. Each celebrates an individual deity. The collection’s titular epithet Homeric is misleading, as the Hymns do not share authorship with the Iliad or Odyssey (nor, for that matter, with each other in most cases, for they are not the work of a single hand).52 Here is the Hymn in question:

[1] I will tell of Dionysus, the son of glorious Semele, how he appeared on a jutting headland by the shore of the fruitless sea, seeming like a stripling in the first flush of manhood: his rich, dark hair was waving about him, and on his strong shoulders he wore a purple robe. Presently there came swiftly over the sparkling sea Etruscan pirates on a well-decked ship — a miserable doom led them on. When they saw him they made signs to one another and sprang out quickly, and seizing him straightway, put him on board their ship exultingly; for they thought him the son of heaven-nurtured kings. They sought to bound him with rude bonds, but these would not hold him, and the ropes fell far away from his hands and feet: and he sat with a smile in his dark eyes.

[15] Then the helmsman understood all and cried out at once to his fellows and said: ‘Madmen! What god is this whom you have taken and bind, strong that he is? Not even the well-built ship can carry him. Surely this is either Zeus or Apollo who has the silver bow, or Poseidon, for he looks not like mortal men but like the gods who dwell on Olympus. Come, then, let us set him free upon the dark shore at once; do not lay hands on him, lest he grow angry and stir up dangerous winds and heavy squalls’.