Untitled Page 03

- Page ID

- 18989

Introduction

What is “Western Civilization”? Furthermore, who or what is part of it? Like al ideas, the concept of Western Civilization itself has a history, one that coalesced in col ege textbooks and curriculums for the first time in the United States in the 1920s. In many ways, the very idea of Western Civilization is a “loaded” one, opposing one form or branch of civilization from others as if they were distinct, even unrelated. Thus, before examining the events of Western Civilization’s history, it is important to unpack the history of the concept itself.

Where is the West?

The obvious question is “west of what”? Likewise, where is “the east”? Terms used in present-day geopolitics regularly make reference to an east and west, as in “Far East,” and

“Middle East,” as wel as in “Western” ideas or attitudes. The obvious answer is that “the West”

has something to do with Europe. If the area including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Israel -

Palestine, and Egypt is somewhere cal ed the “Middle” or “Near” East, doesn't that imply that it is just to the east of something else?

In fact, we get the original term from Greece. Greece is the center-point – to the east of the Balkan Peninsula was east, to the west was west, and the Greeks were at the center of their self-understood world. Likewise, the sea that both separated and united the Greeks and their neighbors, including the Egyptians and the Persians, is stil cal ed the Mediterranean, which means “sea in the middle of the earth” (albeit in Latin, not Greek - we get the word from a later

"Western" civilization, the Romans). The ancient civilizations clustered around the Mediterranean treated it as the center of the world itself, their major trade route to one another and a major source of their food as wel .

To the Greeks, there were two kinds of people: Greeks and barbarians (the Greek word is barbaros ). Supposedly, the word barbarian came from Greeks mocking the sound of non-Greek languages: “bar-bar-bar-bar.” The Greeks traded with al of their neighbors and 3

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

4/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

knew perfectly wel that the Persians and the Egyptians and the Phoenicians, among others, were not their inferiors in learning, art, or political organization, but the fact remains that they were not Greek, either. Thus, one of the core themes of Western Civilization is that right from its inception, of the east being east of Greece and the west being west of Greece, and of the world being divided between Greeks and barbarians, there was an idea of who is central and superior, and who is out on the edges and inferior (or at least not part of the best version of culture).

In a sense, then, the Greeks invented the idea of west and east, but they did not extend the idea to anyone but themselves, certainly including the “barbarians” who inhabited the rest of Europe. Likewise, the Greeks did not invent “civilization” itself; they inherited things like agriculture and writing from their neighbors. Neither was there ever a united Greek empire: there was a great Greek civilization when Alexander the Great conquered what he thought was most of the world, stretching from Greece itself through Egypt, the Middle East, as far as western India, but it col apsed into feuding kingdoms after he died. Thus, while later cultures came to look to the Greeks as their intel ectual and cultural ancestors, the Greeks themselves did not set out to found “Western Civilization” itself.

Mesopotamia

While many contemporary Western Civilization textbooks start with Greece, this one does not. That is because civilization is not Greek in its origins. The most ancient human civilizations arose in the Fertile Crescent, an area stretching from present-day Israel - Palestine through southern Turkey and into Iraq. Closely related, and lying within the Fertile Crescent, is the region of Mesopotamia, which is the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in present-day Iraq. In these areas, people invented the most crucial technology necessary for the development of civilization: agriculture. The Mesopotamians also invented other things that are central to civilization, including:

● Cities: note that in English, the very word “civilization” is closely related to the word

“civic,” meaning “having to do with cities” as in "civic government" or "civic duty." Cities were essential to sophisticated human groups because they al owed specialization: you could have some people concentrate al of their time and energy on tasks like art, building, religious worship, or warfare, not just on farming.

● Bureaucracy: while it seems like a prosaic subject, bureaucracy was and remains the most effective way to organize large groups of people. Civilizations that developed large and efficient bureaucracies grew larger and lasted longer than those that neglected 4

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

5/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

bureaucracy. Bureaucracy is, essential y, the substitution of rules in place of individual human decisions. That process, while often frustrating to individuals caught up in it, does have the effect of creating a more efficient set of processes than can be achieved through arbitrary decision-making. Historical y, bureaucracy was one of the most important "technologies" that early civilizations developed.

● Large-scale warfare: even before large cities existed, the first towns were built with fortifications to stave off attackers. It is very likely that the first kings were war leaders al ied with priests.

● Mathematics: without math, there cannot be advanced engineering, and without engineering, there cannot be irrigation, wal s, or large buildings. The ancient Mesopotamians were the first people in the world to develop advanced mathematics in large part because they were also the most sophisticated engineers of the ancient world.

● Astronomy: just as math is necessary for engineering, astronomy is necessary for a sophisticated calendar. The ancient Mesopotamians began the process of systematical y recording the changing positions of the stars and other heavenly bodies because they needed to be able to track when to plant crops, when to harvest, and when religious rituals had to be carried out. Among other things, the Mesopotamians were the first to discover the 365 (and a quarter) days of the year and set those days into a fixed calendar.

● Empires: an empire is a political unit comprising many different “peoples,” whether

“people” is defined linguistical y, religiously, or ethnical y. The Mesopotamians were the first to conquer and rule over many different cities and “peoples” at once.

The Mesopotamians also created systems of writing, of organized religion, and of literature, al of which would go on to have an enormous influence on world history, and in turn, Western Civilization. Thus, in considering Western Civilization, it would be misleading to start with the Greeks and skip places like Mesopotamia and, also, Egypt, because those areas were the heartland of civilization in the whole western part of Eurasia.

Greece and Rome

Even if we do not start with the Greeks, we do need to acknowledge their importance.

Alexander the Great was one of the most famous and important military leaders in history, a man who started conquering “the world” when he was eighteen years old. When he died his empire fel apart, in part because he did not say which of his generals was to take over after his death. Nevertheless, the empires he left behind were united in important ways, using Greek as one of their languages, employing Greek architecture in their buildings, putting on plays in the 5

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

6/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Greek style, and of course, trading with one another. This period in history was cal ed the Hel enistic Age. The people who were part of that age were European, Middle Eastern, and North African, people who worshiped both Greeks gods and the gods of their own regions, spoke al kinds of different languages, and lived as part of a hybrid culture. Hel enistic civilization demonstrates the fact that Western Civilization has always been a blend of different peoples, not a single encompassing group or language or religion.

Perhaps the most important empire in the ancient history of Western Civilization was ancient Rome. Over the course of roughly five centuries, the Romans expanded from the city of Rome in the middle of the Italian peninsula to rule an empire that stretched from Britain to Spain and from North Africa to Persia (present-day Iran). Through both incredible engineering, the hard work of Roman citizens and Roman subjects, and the massive use of slave labor, they built remarkable buildings and created infrastructure like roads and aqueducts that survive to the present day.

The Romans are the ones who give us the idea of Western Civilization being something ongoing – something that had started in the past and continued into the future. In the case of the Romans, they (sometimes grudgingly) acknowledged Greece as a cultural model; Roman architecture used Greek shapes and forms, the Roman gods were real y just the Greek gods given new names (Zeus became Jupiter, Hades became Pluto, etc.), and educated Romans spoke and read Greek so that they could read the works of the great Greek poets, playwrights, and philosophers. Thus, the Romans deliberately adopted an older set of ideas and considered themselves part of an ongoing civilization that blended Greek and Roman values. Like the Greeks before them, they also divided civilization itself in a stark binary: there was Greco-Roman culture on the one hand and barbarism on the other, although they made a reluctant exception for Persia at times.

The Romans were largely successful at assimilating the people they conquered. They united their provinces with the Latin language, which is the ancestor of al of the major languages spoken in Southern Europe today (French, Italian, Spanish, Romanian, etc.), Roman Law, which is the ancestor of most forms of law stil in use today in Europe, and the Roman form of government. Along with those factors, the Romans brought Greek and Roman science, learning, and literature. In many ways, the Romans believed that they were bringing civilization itself everywhere they went, and because they made the connection between Greek civilization and their own, they played a significant role in inventing the idea of Western Civilization as something that was ongoing.

6

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

7/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

The Middle Ages and Christianity

Another factor in the development of the idea of Western Civilization came about after Rome ceased to exist as a united empire, during the era known as the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages were the period between the fal of Rome, which happened around 476 CE, and the Renaissance, which started around 1300 CE. During the Middle Ages, another concept of what lay at the heart of Western Civilization arose, especial y among Europeans. It was not just the connection to Roman and Greek accomplishments, but instead, to religion. The Roman Empire had become Christian in the early fourth century CE when the emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Many Europeans in the Middle Ages came to believe that, despite the fact that they spoke different languages and had different rulers, they were united as part of

“Christendom”: the kingdom of Christ and of Christians.

Christianity obviously played a hugely important role in the history of Western Civilization. In inspired amazing art and music. It was at the heart of scholarship and learning for centuries. It also justified the aggressive expansion of European kingdoms. Europeans truly believed that members of other religions were infidels (meaning "those who are unfaithful,"

those who worshipped the correct God, but in the wrong way, including Jews and Muslims, but also Christians who deviated from official orthodoxy) or pagans (those who worshipped false gods) who should either convert or be exterminated. For instance, despite the fact that Muslims and Jews worshiped the same God and shared much of the same sacred literature, medieval Europeans had absolutely no qualms about invading Muslim lands and committing horrific atrocities in the name of their religion. Likewise, medieval anti-Semitism (prejudice and hatred directed against Jews) eventual y drove many Jews from Europe itself to take shelter in the kingdoms and empires of the Middle East and North Africa; historical y it was much safer and more comfortable for Jews in places like the predominantly Muslim Ottoman Empire than it was in most of Christian Europe.

A major irony of the idea that Western Civilization is somehow inherently Christian is that Islam is unquestionably just as “Western.” Islam’s point of origin, the Arabian Peninsula, is geographical y very close to that of both Judaism and Christianity. Its holy writings are also closely aligned to Jewish and Christian values and thought. Perhaps most importantly, Islamic kingdoms and empires were part of the networks of trade, scholarship, and exchange that linked together the entire greater Mediterranean region. Thus, despite the fervor of European 7

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

8/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

crusaders, it would be profoundly misleading to separate Islamic states and cultures from the rest of Western Civilization.

The Renaissance and European Expansion

Perhaps the most crucial development in the idea of Western Civilization in the pre-modern period was the Renaissance. The term “Middle Ages” was invented by thinkers during the Renaissance, which started around 1300 CE. The great thinkers and artists of the Renaissance claimed to be moving away from the ignorance and darkness of the Middle Ages –

which they also cal ed the “dark ages” - and returning to the greatness of the Romans and Greeks. People like Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Christine de Pizan, and Petrarch proudly connected their work to the work of the Romans and Greeks, claiming that there was an unbroken chain of ideas, virtues, and accomplishments stretching al the way back thousands of years to people like Alexander the Great, Plato, and Socrates.

During the Renaissance, educated people in Europe roughly two thousand years after the life of the Greek philosopher Plato based their own philosophies and outlooks on Plato's philosophy, as wel as that of other Greek thinkers. The beauty of Renaissance art is directly connected to its inspiration in Roman and Greek art. The scientific discoveries of the Renaissance were inspired by the same spirit of inquiry that Greek scientists and Roman engineers had cultivated. Perhaps most importantly, Renaissance thinkers proudly linked together their own era to that of the Greeks and Romans, thus strengthening the concept of Western Civilization as an ongoing enterprise.

In the process of reviving the ideas of the Greeks and Romans, Renaissance thinkers created a new program of education: “humanist” education. Celebrating the inherent goodness and potentialities of humankind, humanistic education saw in the study of classical literature a source of inspiration for not just knowledge, but of morality and virtue. Combining the practical study of languages, history, mathematics, and rhetoric (among other subjects) with the cultivation of an ethical code the humanistics traced back to the Greeks, humanistic education ultimately created a curriculum meant to create wel -rounded, virtuous individuals. That program of education remained intact into the twentieth century, with study of the classics remaining a hal mark of elite education until it began to be displaced by the more specialized disciplinary studies of the modern university system that was born near the end of the nineteenth century.

8

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

9/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

It was not Renaissance ideas, however, that had the greatest impact on the globe at the time. Instead, it was European soldiers, colonists, and most consequential y, diseases. The first people from the Eastern Hemisphere since prehistory to travel to the Western Hemisphere (and remain - an earlier Viking colony did not survive) were European explorers who, entirely by accident, “discovered” the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century CE. It bears emphasis that the “discovery” of the Americas is a misnomer: mil ions of people already lived there, as their ancestors had for thousands of years, but geography had left them il -prepared for the arrival of the newcomers. With the European colonists came an onslaught of epidemics to which the native peoples of the Americas had no resistance, and within a few generations the immense majority - perhaps as many as 90% - of Native Americans perished as a result. The subsequent conquest of the Americas by Europeans and their descendents was thus made vastly easier. Europeans suddenly had access to an astonishing wealth of land and natural resources, wealth that they extracted in large part by enslaving mil ions of Native Americans and Africans.

Thanks largely to the European conquest of the Americas and the exploitation of its resources and its people, Europe went from a region of little economic and military power and importance to one of the most formidable in the fol owing centuries. Fol owing the Spanish and Portuguese conquest of Central and South America, the other major European states embarked on their own imperialistic ventures in the fol owing centuries. “Trade empires” emerged over the course of the seventeenth century, first and foremost those of the Dutch and English, which established the precedent that profit and territorial control were mutual y reinforcing priorities for European states. Driven by that conjoined motive, European states established huge, and growing, global empires. By 1800, roughly 35% of the surface of the world was control ed by Europeans or their descendents.

The Modern Era

Most of the world, however, was off limits to large-scale European expansion. Not only were there prosperous and sophisticated kingdoms in many regions of Africa, but (in an ironic reversal of the impact of European diseases on Americans) African diseases ensured that would-be European explorers and conquerors were unable to penetrate beyond the coasts of most of sub-Saharan African entirely. Meanwhile, the enormous and sophisticated empires and kingdoms of China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and South Asia (i.e. India) largely regarded 9

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

10/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Europeans as incidental trading partners of relatively little importance. The Middle East was dominated by two powerful and “Western” empires of its own: Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

The explosion of European power, one that coincided with the fruition of the idea that Western Civilization was both distinct from and better than other branches of civilization, came as a result of a development in technology: the Industrial Revolution. Starting in Great Britain in the middle of the eighteenth century, Europeans learned how to exploit fossil fuels in the form of coal to harness hitherto unimaginable amounts of energy. That energy underwrote a vast and dramatic expansion of European technology, wealth, and military power, this time built on the backs not of outright slaves, but of workers paid subsistence wages.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the industrial revolution underwrote and enabled the transformation of Europe from regional powerhouse to global hegemon. By the early twentieth century, Europe and the American nations founded by the descendents of Europeans control ed roughly 85% of the globe. Europeans either forced foreign states to concede to their economic demands and political influence, as in China and the Ottoman Empire, or simply conquered and control ed regions directly, as in South Asia and Africa. None of this would have been possible without the technological and energetic revolution wrought by industrialism.

To Europeans and North Americans, however, the reason that they had come to enjoy such wealth and power was not because of a (temporary) monopoly of industrial technology.

Instead, it was the inevitable result of their inherent biological and cultural superiority. The idea that the human species was divided into biological y distinct races was not entirely invented in the nineteenth century, but it became the predominant outlook and acquired al the trappings of a “science” over the course of the 1800s. By the year 1900, almost any person of European descent would have claimed to be part of a distinct, superior “race” whose global dominance was simply part of their col ective birthright.

That conceit arrived at its zenith in the first half of the twentieth century. The European powers themselves fel upon one another in the First World War in the name of expanding, or at least preserving, their share of global dominance. Soon after, the new (related) ideologies of fascism and Nazism put racial superiority at the very center of their worldviews. The Second World War was the direct result of those ideologies, when racial warfare was unleashed for the first time not just on members of races Europeans had already classified as “inferior,” but on European ethnicities that fascists and Nazis now considered inferior races in their own right, most obviously the Jews. The bloodbath that fol owed resulted in approximately 55 mil ion 10

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

11/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

deaths, including the 6 mil ion Jewish victims of the Holocaust and at least 25 mil ion citizens of the Soviet Union, another “racial” enemy from the perspective of the Nazis.

Western Civilization Is “Born”

It was against the backdrop of this descent into what Europeans and Americans frequently cal ed “barbarism” - the old antithesis of the “true” civilization that started with the Greeks - that the history of Western Civilization first came into being as a textbook topic and, soon, a mainstay of col ege curriculums. Prominent scholars in the United States, especial y historians, came to believe that the best way to defend the elements of civilization with which they most strongly identified, including certain concepts of rationality and political equality, was to describe al of human existence as an ascent from primitive savagery into enlightenment, an ascent that may not have strictly speaking started in Europe, but which enjoyed its greatest success there. The early proponents of the “Western Civ” concept spoke and wrote explicitly of European civilization as an unbroken ladder of ideas, technologies, and cultural achievements that led to the present. Along the way, of course, they included the United States as both a product of those European achievements and, in the twentieth century, as one of the staunchest defenders of that legacy.

That first generation of historians of Western Civilization succeeded in crafting what was to be the core of history curriculums for most of the twentieth century in American col eges and universities, not to mention high schools. The narrative in the introduction in this book fol ows its basic contours, without al of the qualifying remarks: it starts with Greece, goes through Rome, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, then on to the growth in European power leading up to the recent past. The traditional story made a hard and fast distinction between Western Civilization as the site of progress, and the rest of the world (usual y referred to as the “Orient,” simply meaning “east,” al the way up until textbooks started changing their terms in the 1980s) which invariably lagged behind. Outside of the West, went the narrative, there was despotism, stagnation, and corruption, so it was almost inevitable that the West would eventual y achieve global dominance.

This was, in hindsight, a somewhat surprising conclusion given when the narrative was invented. The West’s self-understanding as the most “civilized” culture had imploded with the world wars, but the inventors of Western Civilization as a concept were determined to not only rescue its legacy from that implosion, but to celebrate it as the only major historical legacy of relevance to the present. In doing so, they reinforced many of the intel ectual dividing lines 11

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

12/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

created centuries earlier: there was true civilization opposed by barbarians, there was an ongoing and unbroken legacy of achievement and progress, and most importantly, only people who were born in or descended from people born in Europe had played a significant historical role. The entire history of most of humankind was not just irrelevant to the narrative of European or American history, it was irrelevant to the history of the modern world for everyone .

In other words, even Africans and Asians, to say nothing of the people of the Pacific or Native Americans, could have little of relevance to learn from their own history that was not somehow

“obsolete” in the modern era. And yet, this astonishing conclusion was born from a culture that unleashed the most horrific destruction ( self -destruction) ever witnessed by the human species.

The Approach of This Book (with Caveats)

This textbook fol ows the contours of the basic Western Civilization narrative described above in terms of chronology and, to an extent, geography because it was written to be compatible with most Western Civilization courses as they exist today. It deliberately breaks, however, from the “triumphalist” narrative that describes Western Civilization as the most successful, rational, and enlightened form of civilization in human history. It casts a wider geographical view than do traditional Western Civilization textbooks, focusing in many cases on the critical historical role of the Middle East and North Africa, not just Europe. It also abandons the pretense that the history of Western Civilization was general y progressive, with the conditions of life and understanding of the natural world of most people improving over time.

The purpose of this approach is not to disparage the genuine breakthroughs, accomplishments, and forms of “progress” that did originate in “the West.” Technologies as diverse and important as the steam engine and antibiotics originated in the West. Major intel ectual and ideological movements cal ing for religious toleration, equality before the law, and feminism al came into being in the West. For better and for worse, the West was also the point of origin of true globalization (starting with the European contact with the Americas, as noted above). It would be as misleading to dismiss the history of Western Civilization as unimportant as it is to claim that only the history of Western Civilization is important.

Thus, this textbook attempts to present a balanced account of major events that occurred in the West over approximately the last 10,000 years. “Balance” is in the eye of the reader, however, so the account wil not be satisfactory to many. The purpose of this introduction is to make explicit the background and the framework that informed the writing of 12

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

13/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

the book, and the author chooses to release it as an Open Education Resource in the knowledge that many others wil have the opportunity to modify it as they see fit.

Final y, a note on the kind of history this textbook covers is in order. For the sake of clarity and manageability, historians distinguish between different areas of historical study: political, intel ectual, military, cultural, artistic, social, and so on. Historians have made enormous strides in the last sixty years in addressing various areas that were traditional y neglected, most importantly in considering the histories of the people who were not in power, including the common people of various epochs, of women for almost al of history, and of slaves and servants. The old adage that “history is written by the winners” is simply untrue -

history has left behind mountains of evidence about the lives of the so-cal ed losers, or at least of those who had access to less personal autonomy than did social elites. Those elites did much to author some of the most familiar historical narratives, but those traditional narratives have been under sustained critique for several decades.

This textbook tries to address at least some of those histories, but here it wil be found wanting by many. Given the vast breadth of history covered in its chapters, the bulk of the consideration is on “high level” political history, charting a chronological framework of major states, political events, and political changes. There are two reasons for that approach. First, the history of politics lends itself to a history of events linked together by causality: first something happened, and then something else happened because of it. In turn, there is a fundamental coherence and simplicity to textbook narratives of political history (one that infuriates many professional historians, who are trained to identify and study complexity).

Political history can thus serve as an accessible starting place for newcomers to the study of history, providing a relatively easy-to-fol ow chronological framework.

The other, related, reason for the political framing of this textbook is that history has long since declined as a subject central to education from the elementary through high school levels in many parts of the United States. It is no longer possible to assume that anyone who has completed high school already has some idea of major (measured by their impact at the time and since) events of the past. This textbook attempts to use political history as, again, a starting point in considering events, people, movements, and ideas that changed the world at the time and continue to exert an influence in the present.

To be clear, not al of what fol ows has to do with politics in so many words.

Considerable attention is also given to intel ectual, economic, and to an extent, religious history.

Social and cultural history are covered in less detail, both for reasons of space and the simple fact that the author was trained as an intel ectual historian interested in political theory. These, 13

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

14/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

hopeful y, are areas that wil be addressed in future revisions, particularly in expanding the considerations of women’s history, gender, and the social and cultural history of non-elites in many eras.

Dr. Christopher Brooks

Faculty Member in History, Portland Community Col ege

Original Version: February 2019

14

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

15/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Chapter 1: The Crusades and The High

Middle Ages

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of invasions of the Middle East by Europeans in the name of Christianity. They went on, periodical y, for centuries. They resulted in a shift in the identity of Latin Christianity, great financial benefits to certain parts of Europe, and many instances of horrific carnage. The Crusades serve as one of the iconic points of transition from the early Middle Ages to the “high” or mature Middle Ages, in which the the localized, barter-based economy of Europe transitioned toward a more dynamic commercial economic system.

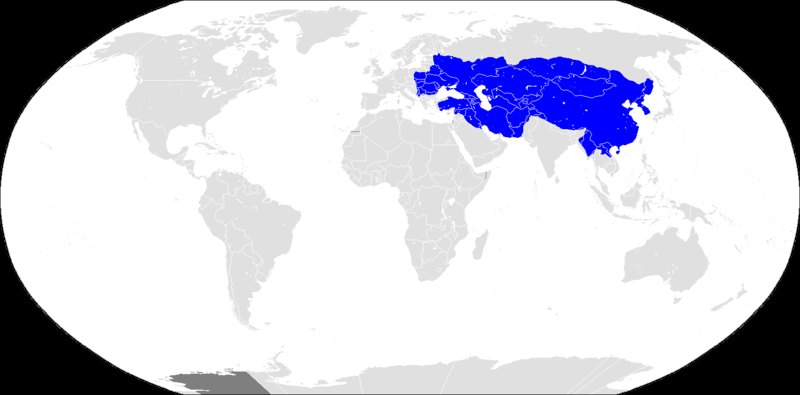

The background to the Crusades was the power of a new Islamic empire in the Middle East, that of the Seljuk Turks. The Seljuks were fierce fighters, trained by their background as steppe nomads and raiders, who had converted to Islam prior to the eleventh century. They proved even more deadly foes to the Byzantine Empire than had the Arab caliphates, and by late in the eleventh century the Byzantine emperor Alexius cal ed for aid from the Christians of western Europe, despite the ongoing divide between the Latin and Orthodox churches.

In 1095, Pope Urban II responded by giving a sermon in France summoning the knights of Europe to holy war to protect Christians in and near the Holy Land. Urban spoke of the supposed atrocities committed by the Turks, the richness of the lands that European knights might expect to seize, and the righteousness of the cause of aiding fel ow Christians. The idea caught on much faster and much more thoroughly than Urban could have possibly expected; knights from al over Europe responded when the news reached them. The idea was so appealing that not only knights, but thousands of commoners responded, forming a “people’s crusade” that marched off for Jerusalem, for the most part without weapons, armor, or supplies.

Much of the impulse of the Crusades came from the fact that Urban II offered unlimited penance to the crusaders, meaning that anyone who took part in the crusade would have al of their sins absolved; furthermore, pilgrims were now al owed to be armed. Thus, the Crusades were the first armed Christian pilgrimage, and in fact, the first “official” Christian holy war in the history of the religion. In addition to the promise of salvation, and equal y important to many of the knights who flocked to the crusading banner, was the promise of loot (and, again, Urban’s speech explicitly promised the crusaders wealth and land). Many of the crusaders were minor 15

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

16/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

lords or landless knights, men who had few prospects back home but now had the chance to make something of themselves in the name of liberating the Holy Land. Thus, most crusaders combined ambition and greed with genuine Christian piety.

The backbone of the Crusades were the knightly orders: organizations of knights authorized by the church to carry out wars in the name of Christianity. The orders came into being after the First Crusade, original y organized to provide protection to Christian pilgrims visiting the Holy Land. They were made up of “monk-knights” who took monastic vows (of obedience, poverty, and chastity) but spent their time fighting as wel as praying. The concept already existed at the start of the crusading period, but the orders grew quickly thanks to their involvement in the invasions. Two orders in particular, the Hospital ers and the Templars, would go on to achieve great wealth and power despite their professed vows of poverty.

The First Four Crusades

The First Crusade (1095 - 1099), which lasted only four years fol owing the initial declaration by Pope Urban, was amazingly successful. The Abbasid Caliphate had long since splintered apart, with rival kingdoms holding power in North Africa and the Middle Ages. The doctrinal differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims further divided the Muslim Ummah. In addition, the Arab kingdoms battled the Seljuk Turks, who were intent on conquering everything, not just Christian lands. Thus, the Crusaders arrived precisely when the Muslim forces were profoundly divided. By 1099, the Crusaders had captured Jerusalem and much of the Levant, forming a series of Christian territories in the heart of the Holy Land. These were cal ed The Latin Principalities, kingdoms ruled by European knights.

16

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

17/228

3/11/2019

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

The Latin Principalities at their height. Note how the Seljuk (here spel ed “Seljuq”) territories almost completely surrounded the principalities.

After their success in taking Jerusalem, the knightly orders became very powerful and very rich. They not only seized loot, but became caravan guards and, ultimately, money-lenders (the Templars became bankers after abandoning the Holy Land when Jerusalem was lost in 1187). Essential y, the major orders came to resemble armed merchant houses as much as monasteries, and there is no question that many of their members did a very poor job of living up to their vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity. Likewise, the rulers of the Latin Principalities made little effort to win over their Muslim and Jewish subjects, treating them instead as sources of wealth, infidels unworthy of humane treatment.

Subsequent Crusades were much less successful. The problem was that, once they had formed their territories, the westerners had to hold on to them with little but a series of strong 17

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

18/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

forts up and down the coast. The European population centers were obviously hundreds or thousands of miles away and the local people were mostly Jews and Muslims who detested the cruel invaders.

Attacks on the Latin Principalities resulted in the Second Crusade, which lasted from 1147 - 1149. The Second Crusade consisted of two Crusades that happened simultaneously: some European knights sailed off to the Holy Land, while others fought against the Cordoban Caliphate in the Iberian Peninsula. The Europeans ultimately lost ground in the Middle East but managed to retake Lisbon in Portugal from the Muslim Caliphate there. In fact, the Second Crusade’s significance is that crusaders began to wage an almost ceaseless war against the Cordoban Caliphate in Spain - in a sense, Christian Europeans, particularly the inhabitants of the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain, concluded that there were plenty of infidels much closer to home than Jerusalem and its environs. These wars of Christians against Spanish Muslims were cal ed the Spanish "Reconquest" ( Reconquista ), and they lasted until the last Muslim kingdom fel in 1492 CE.

In 1187 an Egyptian Muslim general named Salah-ad-Din (his name is normal y anglicized as Saladin) retook Jerusalem after crushing the crusaders at the Battle of Hattin. This prompted the Third Crusade (1189 - 1192), a massive invasion led by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (Frederick Barbarossa), the king of France (Philip II), and the king of England (Richard I - known as "The Lion Heart"). It completely failed, with the English king negotiating a peace deal with Saladin after Frederick died (he drowned trying to cross a river) and Philip returned to France. After this, only a few smal territories remained in Christian hands.

Arguably the most disastrous (in terms of failing to achieve its stated goal of control ing the Holy Land) crusade was the Fourth Crusade, lasting from 1199 – 1204. This latest attempt to seize Jerusalem began with a large group of crusaders chartering passage with Venetian sailors, long since accustomed to profiting from crusader traffic. En route, the crusaders and sailors learned of a succession dispute in Constantinople and decided to intervene. The intervention turned into an outright invasion, with the crusaders carrying out a horrendously bloody sack of the ancient city. In the end, the crusaders set up a Latin Christian government that lasted for about fifty years while completely ignoring their original goal of sailing to the Holy Land. The only lasting effect of the Fourth Crusade was the further weakening of Byzantium in the face of Turkish invaders in the future. To emphasize the point: Christian knights from Western Europe set out to attack the Muslim kingdoms of the Middle East but ended up conquering a Christian kingdom, and the last political remnant of the Roman Empire at that, instead.

18

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

19/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Many further crusades fol owed; popes would continue to authorize official large-scale invasions of the Middle East until the end of the thirteenth century, and the efforts of Christian knights in Spain during the Reconquest very much carried on the crusading tradition for centuries. Later crusades were often nothing more than political y-motivated power grabs on the part of popes, launched against a given pope’s political opponents (i.e. fel ow European Christians who happened to be at odds with a pope). Technical y, the last crusade was the Holy League, an army drawn from various kingdoms in Central and Eastern Europe dispatched to fight the Ottoman Empire in 1684. None of the latter crusades succeeded in seizing land in the Middle East, but they did inspire a relentless drive to overthrow and destroy the now centuries-old Muslim kingdom of Spain, as noted above, and they also inspired the idea of the potential “holiness” of warfare itself among Christians.

Consequences of the Crusades

The Crusades had numerous consequences and effects. Three were particularly important. First, the city-states of northern Italy, especial y Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, grew rich transporting goods and crusaders back and forth between Europe and the Middle East. As the transporters, the merchants, and the bankers of crusading expeditions, it was northern Italians that derived the greatest financial benefit from the invasions. The Crusades provided so much capital that the northern Italian cities evolved to become the banking center of Europe and the site of the Renaissance starting in the fifteenth century.

Second, the ideology surrounding the Crusades was to inspire European explorers and conquerors for centuries. The most obvious instance of this phenomenon was the Reconquest of Spain, which was explicitly seen through the lens of the crusading ideology at the time. In turn, the Reconquest was completed in 1492, precisely the same year that Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas. With the subsequent invasions of South and Central America by the Spanish, the crusading spirit, of spreading Catholicism and seizing territory at the point of a sword, lived on.

Third, there was a new concern with a particularly intolerant form of religious purity among many Christian Europeans during and after the Crusades. One effect of this new focus was numerous outbreaks of anti-Semitic violence in Europe; many crusaders attacked Jewish communities in Europe while the crusaders were on their way to the Holy Land, and anti-Jewish laws were enacted by many kings and lords inspired by the fervent, intolerant new brand of Christian identity arising from the Crusades. Thus, going forward, European Christianity itself became harsher, more intolerant, and more warlike because of the Crusades.

19

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

20/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

The Northern Crusades and the Teutonic Knights

Often overlooked in considerations of the Crusades were the “Northern Crusades” –

invasions of the various Baltic regions of northeastern Europe (i.e. parts of Denmark, northern Germany, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Finland) between 1171, when the Pope Alexander III authorized a crusade against the heathens of the east Baltic, and the early fifteenth century, when the converted kingdoms and territories of the Baltic began to seize independence from their crusading overlords: the Teutonic Knights.

The Teutonic Knights were a knightly order founded during the Third Crusade at a hospital in the Latin city of Acre. They were closely modeled after the Templars, adopting their

“rule” (their code of conduct) and spending most of the twelfth century crusading in the Holy Land. Their focus shifted, however, in the middle of the century when they began leading Crusades against the pagan peoples of the eastern Baltic, including the Lithuanians, Estonians, Finns, and various other groups.

The Baltic lands were the last major region of Europe to remain pagan. Neither Latin nor Orthodox missionaries had made significant headway in converting the people of the region, outside of the border region between the lands of the Rus and the Baltic Sea. Thus, the Teutonic Knights could make a very plausible case for their Crusades as analogous to the Spanish Reconquest, and the Teutonic Knights proved very savvy at placing agents in the papal court that worked to maintain papal support for their efforts.

The Teutonic Order ultimately outlasted the other crusading orders by centuries. The Order was very successful at drumming up support from European princes and knights, relying on annual expeditions of visiting warriors to do most of the fighting while the Teutonic Knights themselves literal y held down the fort in newly-built castles. They were authorized by various popes not only to conquer and convert, but to rule over the peoples of the east Baltic, and thus by the thirteenth century the Teutonic Knights were in the process of conquering and ruling Prussia, parts of Estonia, and a region of southeastern Finland and present-day Lithuania cal ed Livonia. These kingdoms lasted a remarkably long time; the Teutonic Order ruled Livonia al the way until 1561, when it was final y ousted. Thus, for several centuries, the map of Europe included the strange spectacle of a theocratic state: one ruled directly by monk-knights, with no king, prince, or lord above them.

20

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

21/228

3/11/2019

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

The theocracy of the Teutonic Knights as of 1466 (marked in orange and purple along the shores of the Baltic). Note that 1466 fal s squarely into the Renaissance period - the Northern Crusades began during the Middle Ages but their influence lasted far longer.

The Northern Crusades were, in some ways, as important as the Crusades to the Holy Land in that they were responsible for extinguishing the last remnants of paganism in Europe –

it was truly gone by the late fourteenth century in Lithuania, Estonia, and Livonia – and in conquering a large territory that would one day be a core part of Germany itself: Prussia.

The Emergence of the High Middle Ages

The early Middle Ages, from about 500 CE – 800 CE, operated largely on the basis of subsistence agriculture and a barter economy. Economies were almost entirely local; local lords and kings extracted wealth from peasants, but because there was nowhere to sel a surplus of food, peasants tended to grow only as much as they needed to survive, using methods that went unchanged for centuries. There was a limited market for luxury goods even among those 21

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

22/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

wealthy enough to afford them, and the only sources of reliable minted coins were over a thousand miles away, in Byzantium, Persia, and the Arab kingdoms.

This descent into subsistence had happened for various reasons over the course of the earlier centuries. The fal of the western empire of Rome had strangled the manufacture and trade in high-quality consumer goods (a trade that had been very extensive in Rome).

Centuries of banditry, raids, and wars made long-distance travel perilous. In turn, the simple lack of markets meant that there was no incentive to grow more than was needed, and the nobility sought to become more wealthy and powerful not by concerning themselves with agricultural productivity (let alone commerce), but by raiding one another’s lands.

Europe had enjoyed brief periods of relative stability earlier, culminating around 800 CE

during Charlemagne’s rise to power. During the rest of the ninth and tenth centuries, however, the invasions of the Magyars, Saracens, and Vikings had undermined the stability of the fragile political order creating by the Carolingians. Many accounts written at the time, almost exclusively by priests and monks, decried the constant warfare of the period, both that caused by invaders from beyond the European heartland and that between European rulers themselves. Historians now believe that market exchange was growing as a component of the European economy by about 800 CE, but the period between 800 - 1000 was stil one of political instability and widespread violence.

Things started to change around the year 1000 CE. The major causes for these changes were twofold: the end of ful -scale invasions from outside of the core lands of Europe, and changes in agriculture that seem very simple from a contemporary perspective, but were revolutionary at the time.

The Medieval Agricultural Revolution

In 600 CE, Europe had a population of approximately 14 mil ion. By 1300 it was 74

mil ion. That 500% increase was due to two simple changes: the methods by which agriculture operated and the ebb in large-scale violence brought about by the end of foreign invasions.

The first factor in the dramatic increase in population was the simple cessation of major invasions. With relative social stability, peasants were able to consistently plant and harvest crops and not see them devoured by hungry troops or see their fields trampled. Those invasions stopped because the Vikings went from being raiders to becoming members of settled European kingdoms, the Magyars likewise took over and settled in present-day Hungary, and the Saracens were beaten back by increasingly savvy southern-European kingdoms. Warfare between states in Europe remained nearly constant, and banditry stil commonplace in the 22

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

23/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

countryside, but it appears that the overal levels of violence, at least, did drop off over the course of the eleventh century.

Simultaneously, important changes were underway in agricultural technology. Early medieval farmers had literal y scratched away at the soil with light plows, usual y drawn by oxen or donkeys. Plows were like those used in ancient Rome: the weight of the plow was carried in a pole that went across the animal’s neck. Thus, if the load was too heavy the animal would simply suffocate. In turn, that meant that only relatively soft soils could be farmed, limiting the amount of land that could made arable.

A series of inventions led to dramatic changes. Someone (we have no way of knowing who) developed a new kind of col ar for horses and oxen that rested on the shoulders of the animal and thus al owed it to draw much heavier loads, enabling the use of heavier plows.

Those plows were cal ed carruca : a plow capable of digging deeply into the soil and turning it over, bringing air into the topsoil and refreshing its mineral and nutrient content. Simultaneously, iron horseshoes became increasingly common, which dramatical y increased the ability of horses to produce usable muscle power, and iron plowshares proved capable of digging through the soil with greater efficiency.

In addition to the increase in available animal power thanks to those innovations, farmers started to take advantage of new techniques that greatly increased the output of the fields themselves. Up to that point, European farmers tended to employ two-field crop rotation, planting a field while leaving another “fal ow” to recover its fertility for the next year. This system was sustainable but limited the amount of crops that could be grown. Starting around 1000 CE, farmers became more systematic about employing three-field crop rotation: working with three linked fields, they would plant one with wheat, one either with legumes (peas, beans, lentils) or barley, and leave one fal ow, al owing animals to graze on its weeds and leftover stalks from the last season, with their manure helping to fertilize the soil. After harvest, farmers would rotate: the fal ow field would be planted with grain, the grain with legumes, and the legume field left fal ow. This process dramatical y enriched the soil by returning nutrients to it directly with the legumes or at least al owing it to natural y recover while it lay fal ow. Thus, the overal yields of edible crops dramatical y increased. Likewise, with the greater variety, the actual nutritional content of food became better.

Final y, starting in earnest in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, windmil s and watermil s became increasingly common for grinding grains into usable flour. The difference in speed between hand-grinding grain and using a mil was dramatic - it could take most of a day to grind enough flour to bake bread for a family, but a mil could grind fifty pounds of grain in less than a 23

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

24/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

half hour. While peasants resented having to pay for access to mil s (which were general y control ed by landowners, often nobles or the Church), the enormous increase in productivity meant that much more food was available overal . Thus, mil s were stil cost effective for peasants, and mil ed flour became the norm across most of Europe by the end of the twelfth century.

The medieval agricultural revolution had tremendous long-term consequences for peasants and, ultimately, for al of European society Thanks to the increase in animal power and the effects of crop rotation, existing fields became far more productive. Whole new areas were opened to cultivation, thanks to the ability of the carruca to cut through rocky soil As a result, there was a major expansion between 1000 – 1300 from the middle latitudes of Europe farther north and east, as the farming population took advantage of the new technology (and growing population) to clear and cultivate what had been forest, scrub, or swamp. In turn, the existence of a surplus encouraged lords to convert payment in kind (i.e. taxes and rents paid in actual foodstuffs and livestock) to cash rent. Likewise, the relative stability al owed smal er kingdoms to mint their own coins, and over the course of a century or so (c. 1000 – 1100) much of Europe became a cash economy rather than a barter economy. This gave peasants an added incentive to cultivate as much as possible.

Peasants actual y did very wel for themselves in these centuries; they were often able to bargain with their lords for stabilized rents, and a fairly prosperous class of landowning peasants emerged that enjoyed traditional rights vis-à-vis the nobility. Thus, the centuries between 1000

CE - 1300 CE were relatively good for many European peasants. Later centuries would be much harder for them. As an aside, it is important to bear in mind that the progressive view of history, namely the idea that "things always get better over time" is actual y factual y wrong for much of history, as reflected in the lives of peasants in Middle Ages and early modern period.

Cities and Economic Change

The increase in population tied to the agricultural revolution had another consequence: beyond simply improving life for peasants and increasing family size, it led to the growth of towns and cities. Even though most peasants never left the area they were born in, many did migrate to the nearest towns and cities and try to make a life there; serfs (unfree peasants) who made it to a town and stayed a year and day were even legal y liberated from having to return to the farm. Likewise, whole families and even vil ages migrated in search of new lands to farm, general y speaking to the east and north as noted above.

24

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

25/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

This period saw the rebirth of urban life. Not since the fal of Rome had most towns and cities consisted of more than just central hubs of local trade with a few thousand inhabitants. By the twelfth century, however, many cities were expanding rapidly, sometimes by as much as six times in the course of a few centuries. Likewise, the leaders of these cities were often merchants who grew rich on trade, rather than traditional landowning lords.

Even as the agricultural revolution laid the foundation for growth and the cities took advantage of it, other factors led to the economic boom of this period. Lords created new roads and repaired Roman ones from 1,000 years earlier, which al owed bulk trade to travel more cheaply and effectively. More important than bulk goods, however, were luxury goods, a trade almost entirely control ed by the Italian cities during this period. Caravans arrived in the Middle East from China and Central Asia and sold goods to Italian merchants waiting for them. From the Black Sea Region and what was left of Byzantium, the Italians then transported these goods back to the west. Silk and spices were worth far more than their weight in gold, and their trade created the foundation for early financial markets and banks.

Trade networks emerged not only linking Italy to the Middle East but southern to northern Europe. In the Champagne region of France annual fairs brought merchants together to trade their goods. German rivers saw the growth of towns and cities on their banks where goods were exchanged. Starting in the twelfth century, the German city of Lubeck became the capital of the Hanseatic League, a group of cities engaged in trade that came together to regulate exchange and maintain monopolies on goods.

The social consequences were dramatic and widespread, yet the status of merchants in European society was troubled. They were resented by the poor (stil the vast majority of the population), often despised by traditional land-owning nobles, and frequently condemned by the church. Usury , the practice of lending money and charging interest, was classified as a sin by the Church even though the Church itself had to borrow money and pay interest constantly.

Likewise, anti-Semitic stereotypes about Jews as greedy and ruthless arose from the simple fact that dealing in money and money-lending was one of the only professions Jews were al owed to pursue in most medieval kingdoms and cities. Christian Europeans needed loans (as it happens, loans and banking are essential to a functioning cash economy), but despised the Jews they got those loans from - hence the origins of some of the longest-lasting anti-Semitic stereotypes.

Even though cities did not "fit" in the medieval worldview very wel , even the most conservative kings had to recognize the economic strength of the new cities. Just as peasants had been able to negotiate for better treatment, large towns and cities received official town 25

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

26/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

charters from kings in return for stable taxation. In many cases, cities were practical y political y independent, although they general y had to acknowledge the overal authority of the king or local lord.

The growth in trade did not, however, create a real “market economy” in the modern sense. For one thing, skil ed trades were closely regulated by craft guilds, which maintained legal monopolies. Monopolies were granted to guilds by kings, lords, or city governments, and anyone practicing a given trade who was not a member of the corresponding guild could be fined, imprisoned, or expel ed. Guilds jealously guarded the skil s and tools of their trades -

everything from goldsmithing to barrel making was control ed by guilds. Guilds existed to ensure that their members produced quality goods, but they also existed to keep out outsiders and to make the "masters" who control ed the guilds wealthy.

Medieval Politics

The feudal system flourished in the High Middle Ages. While it had its origins in the centuries after the col apse of the western Roman Empire, the formal system of vassals pledging loyalty to kings in return for military service (or, increasingly, in return for cash payments in lieu of military service) real y came of age in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The lords themselves presided over a rigidly hierarchical social and political system in which one’s vocation was largely determined by birth, and the vocation of the nobility was clearly defined by landowning and making war.

Lords - meaning land-owning nobles - lived in “manors,” a term that denoted not only their actual houses but the lands they owned. Al of the peasants on their lands owed them rent, original y in the form of crops but eventual y in cash, as wel as a certain amount of labor each year. Peasants were subdivided into different categories, including the relatively-wel off independent yeomen and freeholders, who owned their own plots of land, down to the serfs, semi-free peasants tied to the land, and then the cottagers, who were the landless peasants worse-off even than serfs. The system of land-ownership and the traditional rights enjoyed by not just lords, but serfs and freeholders who lived under the lords, is referred to as

“manorialism,” the rural political and economic system of the High Middle Ages as a whole.

One of the traditional rights, and a vital factor in the lives of peasants, were the commons: lands not official y control ed by anyone that al people had a right to use. The commons provided firewood, grazing land, and some limited trapping of smal animals, col ectively serving as a vital “safety net” for peasants living on the edge of subsistence. Access 26

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

27/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

to the commons was not about written laws, but instead the traditional, centuries-old agreements that governed the interactions between different social classes. Eventual y, peasants would find their access to the commons curtailed by landowning nobles intent on converting them to cash-producing farms, but for the medieval period itself, the peasants continued to enjoy the right to their use.

The kingdoms of Europe up to this point were barely unified. In many cases, kings were simply the most powerful nobles, men who extracted pledges of loyalty from their subjects but whose actual authority was limited to their personal lands. Likewise, kings in the early Middle Ages were largely itinerant, moving from place to place al year long. They had to make an annual circuit of their kingdoms to ensure that their powerful vassals would stay loyal to them; a vassal ignored for too long could, and general y did, simply stop acknowledging the lordship of his king. Those patterns started to change during the High Middle Ages, and the first two kingdoms to show real signs of centralization were France and England.

In France, a series of kings named Philip (I through IV) ruled from 1060 to 1314, building a strong administrative apparatus complete with royal judges who were directly beholden to the crown. The kings ruled the region around Paris (cal ed the Île-de-France , meaning the "island of France"), but their influence went wel beyond it as they extended their holdings. Philip IV even managed to seize almost complete control of the French Church, defying papal authority. He also proved incredibly shrewd at creating new taxes and in attacking and seizing the lands and holdings of groups like the French Jewish community and the Knights Templar, both of whom he ransacked (the assault on the Knights Templar started in 1307).

In England, the line descending from Wil iam the Conqueror (fol owing his invasion in 1066) was also effective in creating a relatively stable political system. Al land was legal y the king’s, and his nobles received their lands as “fiefs,” essential y loans from the crown that had to be renewed for payments on the death of a landholder before it could be inherited. Henry II (r.

1154 – 1189) created a system of royal sheriffs to enforce his wil , created circuit courts that traveled around the land hearing cases, and created a grand jury system that al owed people to be tried by their peers.

In 1215, a much less competent king named John signed the Magna Carta (“great charter”) with the English nobility that formal y acknowledged the feudal privileges of the nobility, towns and clergy. The important effect of the Magna Carta was its principle: even the king had to respect the law. Thereafter English kings began to cal the Parliament, a meeting of the Church, nobles, and wel -off commoners, in order to get authorization and money for their wars.

27

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

28/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Monasticism

One special social category within medieval society deserves added attention: the monks and nuns. Monks and nuns took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience when they left their normal lives and joined (respectively) monasteries and convents. They did not, however, have to spend their time attending to the spiritual needs of laypeople (i.e. people outside of the Church), which was the primary function of priests. Instead, they were to devote themselves to prayer and to useful works, activities that were thought to encourage piety and devotion among the monks and nuns, and which often proved to be extremely profitable to the monasteries and convents themselves.

Monasteries and convents grew to become some of the most important economic institutions in medieval Europe, despite their stated intention of housing people whose ful -time job was to pray for the souls of Christians everywhere. Monasteries and convents had to be economical y self-sustaining, overseeing both agriculture and crafts on their lands. Over time, activities like overseeing agriculture on monastery lands, brewing beer or making wine, or painstakingly copying the manuscripts of books often became a major focus of life in monasteries and convents. In essence, many monasteries and convents became the most dynamic and commercial y successful institutions in their home regions. Monks and nuns encouraged innovative new forms of agriculture on their lands, sold products (including textiles and the above-mentioned beer and wine) at a healthy profit, and despite their vows of poverty, successful monasteries and convents became lavishly decorated and luxurious for their inhabitants.

Simultaneously, one way that medieval elites tried to shore up their chances of avoiding eternal damnation was leaving land and wealth in their wil s to monasteries and convents.

Generations of European elites granted land, in particular, to monasteries and convents during life or as part of their posthumous legacy. The result was the astonishing statistic that monasteries owned a ful 20% of the arable land of Western Europe by the late Middle Ages.

Corruption

Monasteries and convents were not alone in their wealth. The upper ranks of the Church - bishops, archbishops, cardinals, and the popes themselves - were almost exclusively drawn from the European nobility. Lower-ranking churchmen were, in turn, commoners, often drawn from the ranks of the same peasants that they ministered to from one of the smal parish churches that dotted the landscape. Al of the wealth that went into the Church, from an 28

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

29/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

obligatory tax cal ed the tithe, was siphoned up to the upper reaches of the institutional Church, and many of the high-level priests lived like princes as a result.

Morality in this setting was, predictably, lax. Despite the nominal requirement not to marry, many high-level priests lived openly with concubines and equal y openly supported their children, seeing their sons set up as landowners or members of the Church in their own right and marrying off daughters to noble families. Despite the injunction to live simply and avoid luxury, many priests (and monks, and nuns) were greedy and ostentatious; one notorious practice was of bishops or archbishops who control ed and received incomes from many different territories (cal ed "bishoprics") at once but never actual y visited them. Another practice was of noblemen literal y buying positions in the Church for their sons - teenage boys might find themselves appointed bishops thanks to the financial intervention of their fathers, with Church officials pocketing the bribe. Medieval depictions of hel were ful of the image of priests, monks, and nuns al plummeting into the fire to face eternal torment for what a profoundly poor job they had done while alive in living up to the moral demands of their respective vocations. In other words, medieval laypeople were wel aware of how corrupt many in the Church actual y were.

In addition, while medieval education and literacy was almost entirely confined to the church as an institution, many rural priests were at best semi-literate. Al Church services were conducted in Latin, and yet some priests understood Latin only poorly, if at al (it had long since vanished as a vernacular language in Europe). Thus, some of the very caretakers of Christian belief in medieval society often had a very shal ow understanding of what that belief was supposed to consist of theological y.

For al of the Middle Ages, however, the fact that the lay public knew that the Church was corrupt and that many of its members were incompetent was of limited practical importance.

There was no alternative. Without the Church, without the sacraments only it could offer, without the prayers issued by monks and nuns for the souls of believers, and without its reassurance of a life to come after death, medieval Christians were certain that their eternal souls were damned to hel .

29

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

30/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

Medieval Learning

Despite the biases of later Renaissance thinkers that the medieval period was nothing but the “dark ages,” bereft of learning and culture, there were very important intel ectual achievements in the period of 1000 – 1400 CE. Most of these had to do with foreign influences that were taken and reshaped by European thinkers, from the ancient Greeks and Romans to innovations originating in the Islamic empires to the south and east of Europe.

Likewise, despite the problems of corruption and ignorance among members of the clergy, scholarship did continue and even prosper within the church during the late Middle Ages.

Numerous priests were not only literate in Latin and deeply knowledgeable about Christian theology, but made major strides in considering, debating, and explaining the nuances of Christian thought. Thus, it is a mistake to consider the medieval church as nothing more than a kind of "scam" - it did provide meaningful guidance and comfort to medieval Christians, and some of its members were exemplary thinkers and major intel ectuals.

Intel ectual Life in the Middle Ages

A symptom of the growth of intel ectual life in the High Middle Ages was the fact that literacy (which, at the time, meant the ability to read, not necessarily to write) final y revived, at least a bit, fol owing the real nadir of literacy that had lasted from the col apse of the western Roman Empire until about 1050. As of 1050, perhaps 1% of the population could read, most of whom were priests, some of the latter only being able to stumble through the Latin liturgy without ful y comprehending it. While it is impossible to calculate anything close to the exact literacy rates at any point before the modern era, it is stil clear that literacy started to climb fol owing that eleventh-century low point, with many regular merchants and even a few peasants acquiring at least basic reading knowledge by the fourteenth century. The explanation for this growth in literacy is an expansion of educational institutions that had only existed in a few pockets earlier in the Middle Ages.

The two forms of educational institutions available were tutoring offered within monasteries and schools associated with cathedrals. Both were, obviously, part of the Church, and cathedral schools in particular focused on training future priests. Monasteries offered basic education in literacy (in Latin) to laypeople as wel as the monks themselves, and even some prosperous farmers achieved a basic degree of literacy as a result. Cathedral schools in cities 30

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

31/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

offered the same, and they increasingly trained not only local elites, but even the children of artisans and merchants.

While they did offer basic education to laypeople, the official focus of cathedral schools was in training priests. They began to expand after 1000 CE, offering a more focused and rigorous grounding in sacred texts and, to an extent, ancient texts from Rome, to help educate Church leaders and laypeople. The cathedral schools were supposed to be turning out not just spiritual leaders, but skil ed bureaucrats, and that required a rigorous form of education that encouraged the study not just of the Bible, but of classics of Latin literature like the speeches of the great Roman politician Cicero and ancient Rome's great epic poem, Virgil's Aeneid . Thus, those priests-in-training who were lucky enough to attend one of the better cathedral school acquired a strong command of classical Latin and were made aware of the high intel ectual standards that had prospered in the glory days of Rome.

Scholasticism

If there was a single event that changed education and scholarship in the late Middle Ages, it was the arrival of the lost works of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. Aristotle was one of the greatest geniuses of the ancient world, producing learned works on philosophy, astronomy, physics, biology, literary criticism and, most importantly for medieval Europe, logic.

Some of Aristotle's works had survived in Europe after the fal of Rome, but most of it had vanished. Over the course of the eleventh century, translations of Aristotle's work on formal philosophical logic re-emerged in Europe. Most had been preserved in the Arab world, where Aristotle was considered the single most important pre-Islamic philosopher and was studied with great rigor by Arab scholars. Enterprising scholars - many of them Jewish philosophers who lived in North Africa and Spain - translated Aristotle's work on logic from Arabic into Latin. Later, Greeks from Byzantium came to Europe with the originals in Greek and they, too, translated it into Latin.

The importance of this rediscovery of Aristotle is that his work on logic offered a formal system for evaluating complicated bodies of work like the Christian Bible itself. The inherent problem facing believers of any religion based on a single major text is figuring out what that text fundamental y means . To wit: the Christian Bible is ful of parables, stories, and accounts of events that are often terrifical y difficult to interpret. Even in the four gospels that describe the life of Christ, not al of Christ's actions or sayings are easy to understand, and the gospels sometimes offer conflicting accounts. What did Christ mean when he said "Again I tel you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the 31

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1...XpcG3CyY/edit#

32/228

Western Civilization: A Concise History - Volume 2 - Google Docs Western Civilization: A Concise History

kingdom of God" (Matthew 19:24)? What did he mean with "Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword" (Matthew 10:34)? Not to mention, how was a Christian to make sense of the stern, vengeful God described in the Old Testament and the deity of peace and forgiveness represented by Christ? Most medieval Christians were content to simply accept the sacraments and offer prayers to the saints without worrying about the theological details, but increasingly, educated priests themselves wanted to understand the nuances of their own religion.

Thus, Aristotle’s formal approach to logic proved invaluable to the interpreters of the Bible. Armed with his newly-rediscovered system of logical interpretation, key figures within the Church began to analyze the Bible and the works of early Christian thinkers with new energy and focus. The result was scholasticism, which was the major intel ectual movement of the High Middle Ages. Scholasticism was the rigorous application of methods of logic, original y developed by Aristotle, to Christian scriptures. And, because the cathedral schools of the late Middle Ages increasingly relied on scholasticism to train and teach new priests, it spread rapidly across al of Europe.