7: Untitled Page 03

- Page ID

- 19008

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

He wrote several important polemical tracts, attacking the theology at Massachusetts Bay Colony and advocating for the separation of church and state.

His Christenings Make Not Christians calls out those in the New World who claim to be practicing Christians, who cling more to form than real practice of charity for all humans on earth, including Native Americans.

Image 2.5 | The Return of Roger Williams

Artist | C. R. Grant

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

2.5.1 Christenings Make Not Christians

(1645)

A Briefe Discourse concerning that name HEATHEN Commonly given to the Indians. As also concerning that great point of their conversion.

Shall first be humbly bold to inquire into the name Heathen, which the English give them, & the Dutch approve and practise in their name Heydenen, signifying Heathen or Nations. How oft have I heard both the English and Dutch (not onely the civill, but the most ded bauched and profane) fay, These Heathen Dogges, better kill a thousand of them then that we Christians should be indangered or troubled with them; Better they were all cut off, & then we shall be no more troubled with them: They have spilt our Christian bloud, the best way to make riddance of them, cut them all off, and fo make way for Christians.

I shall therefore humbly intreat my country-men of all forts to consider, that although men have used to apply this word Heathen to the Indians that go naked, and have not heard of that One-God, yet this word Heathen is most improperly Page | 148

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

sinfully, and unchristianly so used in this fence. The word Heathen signifieth no more then Nations or Gentiles; so do our Translations from the Hebrew and the Greeke in the old and New Testament promiscuoufly render these words Gentiles, Nations, Heathens.

Why Nations? Because the Jewes being the onely People and Nation of God, esteemed (and that rightly) all other People, not only those that went naked, but the famous BABYLONIANS, CALDEANS, MEDES, and PERSIANS, GREEKES

and ROMANES, their stately Cities and Citizens, inferiour themselves, and not partakers of their glorious privileges, but Ethnicke, Gentiles, Heathen, or the Nations of the world.

Now then we must enquire who are the People of God, his holy nation, snce the comming of the Lord Jesus, and the rejection of his first typicall holy Nation the Jewes.

It is confest by all, that the CHRISTIANS the followers of Jesus, are now the onely People of God, his holy nation, &c. 1. Pet. 2. 9.

Who are then the nations, heathen, or gentiles, in opposition to this People of Goa? I answer, All People, civilized as well as uncivilized, even the most famous States, Cities, and the Kingdomes of the World: For all must come within that distinction. 1. Cor. 5. within or without.

Within the People of God, his Church at CORNITH: Without the City of CORINTH worshipping Idols, and so consequently all other People, HEATHENS, or NATIONS, opposed, to the People of God, the true Jewes: And therefore now the naturall Jewes themselves, not being of this People, are Heathens Nations or Gentiles. Yea, this will by many hands be yeelded, but what say you to the Christian world? What say you to Christendome? I answer, what do you thinke Peter or John, or Paul, or any of the first Messengers of the Lord Jesus; Yea if the Lord Jesus himselfe were here, (as he will be shortly) and were to make answer, what would they, what would he fay to a CHRISTIAN WORLD? To CHRISTENDOME?

And otherwise then what He would speak, that is indeed what he hath spoken, and will shortly speake, must no man speak that names himselfe a Christian.

Herdious in his Map of his CHRISTIAN WORLD takes in all Asia, Europe, a vaste part of Africa, and a great part also of America, so far as the Popes Christnings have reached to.

This is the CHRISSION WORLD, or Christendome, in which respect men stand upon their tearmes of high opposition between the CHRISTIAN and the TVRKE, (the Chriftian shore, and the Turkish shore) betweene the CHRISTIANS of this Christian WORLD and the JEVV, and the CHRISTIAN and the HEATHEN, that is the naked American.

But since Without is turned to be Within, the WORLD turned CHRISTIAN, and athe ittle flocke of JESVS CHRIST hath so marvelllously increased in such wonderfull converfions, let me be bold to aske what is Christ? What are the Christians? The Hebrew and the Greeke will tell us that Christ was and is the Anointed of God, whom the Prophets and Kings and preists of Israel in their anointings did prefigure and Page | 149

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

type out; whence his followers are called christians, that is Anointed also: So that indeed to be a christian implyes two things, first, to be afollower of that anointed one in all his Offices; secondly, to pertake of his anointings, for the Anointing of the Lord Jesus (like to the anointings of AARON, to which none might make the like on pain of death) descend to the skirt of his garments.

To come nearer to this Christion world, (where the world becomes christian holy, anointed, Gods People, &c.) what faith John? What faith the Angel? Yea, What faith Jesus Christ and his Father (from whom the Revelation came Revel 1.

1.) What fay they uuto the Beast and his Worshippers Revel. 13.

If that beast be not the Turke, northe Roman Emperour (as the grosest interpret- but either the generall councels, or the catholike church of Rome, or the Popes or Papacy (as the most refined interpret) why then all the world, Revel. 13.

wonders after the Beast, worships the Beast, followeth the Beast, and boasts of the Beast, that there is none like him, and all People, Tongues, and Nations, come under the power of this Beast, & no man shall buy nor fell, nor live, who hath not the marke of the Beast in his Fore-head, or in his hand, or the number of his name.

If this world or earth then be not intended of the whole terrestriall Globe, Europe, Asia, Africa and America, (which fence and experience denyes) but of the Roman earth, or world, and the People, Languages, and Nations, of the Roman Monarchy, transferred from the Roman Emperour to the Roman Popes, and the Popish Kingdomes, branches of that ROMAN-ROOT, (as all history and consent of time make evident.)

Then we know by this time what the Lord Jesus would say of the Christian world and of the Christian: Indeed what he saith Revel. 14. If any man worship the Beast or his picture, he shall drinke &c. even the dread fullest cup that the whole Booke of God ever held forth to snners. Grant this, say some of Popish Countries, that notwithstanding they make up Christendome, or Christian world, yet submitting to that Beast, they are the earth or world and must drinke of that most dreadfull cup: But now for those nations that have withdrawn their necks from that beastly yoke, & protesting against him, are not Papists, but Protestants, shall we, may we thinke of them, that they, or any of them may also be called (in true Scripture fence) Heathens, that is Nations or Gentiles, in opposition to the People of God, which is the onely holy Nation.

I answer, that all Nations now called Protestants were at first part of that whole Earth, or main (ANTICHRISTIAN) Continent, that wondered after, worshipped the Beast, &c. This must then with holy feare and trembling (because it concernes the KINGDOME of God, and salvation) be attended to, Whether such a departure from the Beast, and coming out from ANTICHRISTIAN abominations, from his markes in a false converson, and a false constitution, or framing of NATIONAL

CHVRCHES in false MINISTERIES, and ministrations of BAPTISME, Supper of the Lord, Admonitions, Excommunications as amounts to a true perfect Iland, cut off from that Earth which wonderd after and worshipped the Beast: or-whether, not being so cut off, they remaine not Peninsulâ or necks of land, contiguous Page | 150

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

and joyned still unto his Christtendome? If now the bodies of Protestant Nations remaine in an unrePentant, unregenerate, naturall estate, and so consequently farre from hearing the admonitions of the Lord Jesus, Math 18. I lay they must sadly consder and know (least their profession of the name of Jesus prove at last but an aggravation of condemnation) that Christ Jesus hath faid, they are but as Heathens and Publcanes, vers. 17. How might I therefore humbly beseech my counry men to consider what deepe cause they have to fearch their conversons from that Beast and his Pisture?’ And whether having no more of Christ then the name (besde the invented wayes of worship, derived from, or drawn after Romes pattern) their hearts and conversations will not evince them unconverted and unchristian Christians, and not yet knowing what it is to come by true Regeneration within, to the true spirituall Jew from without amongst the Nations, that is Heathens or Gentiles.

How deeply and eternally this concerns each foule to search into! yea, and much more deeply such as professe to be Guides, Leaders, and Builders of the HOUSE OF GOD.

First, as they look to Formes and Frame of Buildings, or Churches.

Secondly, as they attend to Meanes and Instruments, &c.

Thirdly, as they would lay sure Foundations; and lasting Groundfells.

Fourthly, as they account the cost and charge such buildings will amount unto.

Fifthly, so they may not forget the true spirituall matter and mateaials of which a true House, Citty, Kingdome, or Nation of of God, now in the new Testament are to be composed or gathered.

Now Secondly, for the hopes of CONVERSION, and turning the People of America unto God: There is no respect of Persons with him, for we are all the worke of his hands; from the rising of the Sunne to the going downe thereof, his name shall be great among the nations from the Eats: & and from the West, &c. If we respect theirsfins, they are far short of European sinners: They neither abuse such corporall mercies for they have them not; nor sin they against the Gospell light, (which shines not amongst them) as the men of Europe do: And yet if they were greater sinners then they are, or greater sinners then the Europeans, they are not the further from the great Ocean of mercy in that respect.

Laftly, they are intelligent, many very ingenuous, plaine-hearted, inquisitive and (as I said before) prepared with many convictions, &c.

Now secondly, for the Catholicks conversion, although I believe I may safely hope that God hath his in Rome, in Spaine, yet if Antichrist be their false head (as most true it is) the body, faith, baptisme, hope (opposte to the true, Ephef. 4.) are all false also; yea consequently their preachings, conversons, salvations (leaving fecret things to God) must all be of the same false nature likewise.

If the reports (yea some of their owne Historians) be true, what monstrous and molt inhumane conversons have they made; baptizing thousands, yea ten thousands of the poore Natives, sometimes by wiles and subtle devices, sometimes by force compelling them to submit to that which they understood not, neither Page | 151

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

before nor after such their monstrous Christning of them. Thirdly, for our New-endland parts; I can speake uprightly and confidently, I know it to have been easie for my selfe, long ere this, to have brought many thousands of these Natives, yea the whole country, to a far greater Antichristian conversion then ever was yet heard of in America. I have reported something in the Chapter of their Religion, how readily I could have brought the whole Country to have observed one day in seven; I adde to have received a Baptisme (or washing) though it were in Rivers (as the first Christians and the Lord Jesus himselfe did) to have come to a stated Church meeting, maintained priests and formes of prayer, and a whole forme of Antichristian worship in life and death. Let none wonder at this, for plausible perswations in the mouths of those whom naturall men esteem and love: for the power of prevailing forces and armies hath done this in all the Nations (as men speake) of Christendome. Yea what lamentable experience have we of the Turnings and Turnings of the body of this Land in point of Religion in few yeares?

When England was all Popish under Henry the the seventh, how ease is conversion wrought to halfe Papist halfe-Protestant under Henry the eighth?

From halfe-Proteftanifme halfe-Popery under Henry the eight, to absolute Protestanisme under Edward the sxth: from absoluer Protestation under Edward the sixt to absalute popery under Quegne Mary, and from absolute Popery under Queene Mary, (just like the Weather-cocke, with the breatq of every Prince) to absolute Protestanisme under Queene Elizabeth &c.

For all this, yet some may aske, why hath there been such a price in my hand not improved? why have I not brought them to such a conversion as I speake of?

I answer, woe be to me, if I call light darknesse, or darknesse light; sweet bitter, or bitter sweet; woe be to me if I call that conversion unto God, which is indeed subversion of the soules of Millions in Christendome, from one false worship to another, and the prophanation of the holy name of God, his holy Son and blessed Ordinances. America (as Europe and all nations) lyes dead in sin and trespasses: It is not a fuite of crimson Satten will make a dead man live, take off and change his crimson into white he is dead still, off with that, and shift him into cloth of gold, end from that to cloth of diamonds, he is but a dead man still: For it is not a forme, nor the change of one forme into another, a finer, and a finer, and yet more fine, that makes a man a convert I meane such a convert as is acceptable to God in Jesus Christ, according to the visible Rule of his last will and Testament. I speake not of Hypocrites, (which may but glister, and be no solid gold as Simon Magus, Judas &c.) But of a true externall converson; I say then, woe be to me if intending to catch men (as the Lord Jesus said to Peter) I should pretend converson) and the bringing of men as mistical fish, into a Church-estate, that is a converted estate, and so build them up with Ordinances as a converted Christian People, and yet afterward still pretend to catch them by an after converson. I question not but that it hath pleased God in his infinit pitty and patience, to fuffer this among us, yea and to convert thousands, whom all men, yea and the persons (in their personall estates converted) have esteemed themselves good converts before.

Page | 152

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

But I question whether this hath been so frequent in these late yeares, when the times of ignorance (which God pleaseth to pase by) are over, and now a greater light concerning the Church, Ministery, and conversion, is arisen. I question whether if such rare talents, which God hath betrusted many of his precious Worthies with, were laid out (as they shall be in the Lord’s molt holy season) according to the first pattern; I say, I question whether or no, where there hath been one (in his personall estate converted) there have not been, and I hope in the Lords time shall be, thousands truly converted from Antichristian Idols (both in person and worship) to serve the living and true God.

And lastly, it is out of question to me, that I may not pretend a false conversion, and false state of worship, to the true Lord Jesus.

If any noble Berean shall make inquiry what is that true conversion I intend; I answer first negatively.

First, it is not a converson of a People from one false worship to another, as Nebuchadnezzer compeld all Nations under his Monarchy.

Secondly, it is not to a mixture of the manner or worship of the true God, the God of Israel, with false gods & their worships, as the People were converted by the King of Assyria, 2, Kin. 17. in which worship for many Generations did these Samaritans continue, having a forme of many wholsome truths amongst them, concerning God and the Messiah, Ioh. 4.

Thirdly, it is not from the true to a false, as IEREBOAM turned the ten Tribes to their mine and disperson unto this day, 1. Kin. 12.

Fourthly, it must not be a conversion to some externall submisson to Gods Ordinances upon earthly respects, as JACOBS sons converted the Sichemites, Gen. 34.

Fiftly it mustnot be, (it is not poslible it should be in truth) a converson of People to the worship of the Lord Jesus, by force of Armes and swords of steele: So indeed did Nebuchadnezzer deale with all the world, Dan. 3. to doth his Antitype and successorr the Beast deal with all the earth, Rev. 13. &c.

But so did never the Lord Jesus bring any unto his most pure worship, for he abhorres (as all men, yea the very Indians doe) an unwilling Spouse, and to enter into a forced bed: The will in worship, if true, is like a free Vote, nec cogit, nec cogitur: JESVS CHRIST compells by the mighty perswasons of his Messengers to come in, but otherwise with earthly weapons he never did compell nor can be compelled. The not discerning of this truth hath let out the bloud of thousands in civill combustions in all ages; and made the whore drunke, & the Earth drunk with the bloud of the Saints, and witnesses of Jesus.

And it is yet like to be the destruction & and dissolution of (that which is called) the Christian world, unlesse the God of peace and pity looke downe upon it, and satisfy the soules of men, that he hath not so required. I should be far yet from unsecuring the peace of a City, of. a Land, (which I confesse ought to be maintained by civill weapons, & which I have so much cause to be earnest with God for;) Nor Page | 153

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

would I leave a gap open to any mutinous hand or tongue, nor wish a weapon left in the hand of any known to be mutinous and peace-breakers.

I know (lastly) the consciences of many are otherwise perswaded, both from Israels state of old, and other Allegations; yet I shall be humbly bold to lay, I am able to present such considerations to the eyes of all who love the Prince of truth and Peace, that shall discover the weaknesse of all such allegations, aud answer all objections, that have been, or can be made in this point. So much negatively.

Secondly, affirmatively: I answer in generall, A true Conversion (whether of Americans or Europeans) must be such as those Conversions were of the first pattern, either of the Jewes or the Heathens; That Rule is the golden Mece wand in the hand of the Angell or Messenger, rev. 11. 1. besde which all other are leaden and crooked.

In particular: First, it must be by the free proclaiming or preaching of Repentance & forgivenesse of sins. Luk. 24. by such Messengers as can prove their lawfull fending and Commission from the Lord Jesus, to make Disciples out of all nations: and so to baptize or wash them into the name or profession of the holy Trinity, Mat, 28. 19 Rom. 10. 14. 15.

Secondly, such a conversion (so farre as mans Judgement can reach which is fallible, (as was the judgement of the first Messengers, as in Simon Magus, &c.) as is a turning of the whole man from the power of Sathan unto God, act. 26. Such a change, as if an old man became a new Babe Ioh. 3. yea, as amounts to Gods new creation in the soule, Ephes, 2. 10.Thirdly, Visibly it is a turning from Idols not only of conversation but of worhsip (whether Pagan, Turkish, Jewish, or Antichristian) to the Living and true God in the waies of his holy worship, appointed by his Son, 1 Thes. 1. 9.

I know Objections use to be made against this, but the golden Rule, if well attended to, will discover all crooked swervings and aberrations.

If any now say unto me, Why then if this be Conversion, and you have such a Key of Language, and such a dore of opportunity, in the knowledge of the Country and the inhabitants, why proceed you not to produce in America some patternes of such conversions as you speake of?

I answer, first, it must be a great deale of practise, and mighty paines and hardship undergone by my selfe, or any that would proceed to such a further degree of the Language, as to be able in propriety of speech to open matters of salvation to them. In matters of Earth men will helpe to spell out each other, but in matters of Heaven (to which the soule is naturally so averse) how far are the Eares of man hedged up from listening to all improper Language?

Secondly, my dsfires and endeavours are constant (by the helpe of God) to attaine a propriety of Language.

Thirdly, I confesse to the honour of my worthy Countrymen in the Bay of Massachuset, and elsewhere, that I received not longsfince expressions of their holy desires and prossers of assistance in the worke, by the hand of my worthy friend Colonell Humphreys, during his abode there.

Page | 154

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Yet fourthly, I answer, if a man were as affectionate and zealous as David to build an house for God, and as wife and holy to advise and incourage, as Nathan, attempt this worke without a Word, a Warrant and Comimission, for matter, and manner, from GOD himselfe, they must afterwards heare a voice (though accepting good desires, yet reproving want of Commission) Did I ever speak a word saith the Lord? &c. 2. Sam. 7. 7.

The truth is, having not been without (through the mercy of God) abundant and constant thoughts about a true Commission for such an Embassie and Ministery.

I must ingenuousy confesse the restlesse unsatisfiednesse of my soule in divers main particulars:

As first, whether (snce the Law must go forth from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem) I say whether Gods great businesse between Christ Jesus the holy Son of God and Antichrist the man of sin and Sonne of perdition, must not be first over, and Zion and Jerusalem be re-built and re-established, before the Law and word of life be sent forth to the rest of the Nations of the World, who have not heard of Christ: The Prophets are deep concerning this.

Secondly snce there can be no preaching (according to the last Will and Testament of Christ Jesus) without a true sending Rom. 14. 15 Where the power and authority of sending and giving that Commission on Math. 28 &c. I say the question is where that power now lyes?

It is here unseasonable to number up all that lay claime to this Power, with their grounds for their pretences, either those of the Romish fort, or those of the Reforming or Re-building fort, and the mighty controverses which are this day in all parts about it: in due place (haply) I may present such sad Queries to consideration, that may occasion some to cry with DANIEL (concer-JERVSALEMS

desolation Dan. 9.) Under the whole Heaven hath not been done, as hath been done to JERVSALEM: and with JEREMY in the fame respect, Lam. 2. 12. Have you no respect all you that passe by, behold and see there were ever sorrow like to my sorrow, wherewith the Lord hath afflicted me in the day of his fierce wrath.

That may make us ashamed for all that wee have done, Ezek. 43 and loath our selves, for that (in whorish worships) wee have broken him with our whorish hearts Ezek. 9. To fall dead at the feet of JESVS, Rev. 1. as JOHN did, and to weepe much as hee Rev. 5. that so the LAMB may please to open unto us that WONDERFVLL

BOOK and the seven SEALED MYSTERIES thereof.

Your unworthy Country-man

ROGER WILLIAMS.

2.5.2 Reading and Review Questions

1. How does Williams distinguish Native Americans from “heathens?”

Why, do you think?

2. What criticisms does Williams make against many Christians who have converted Native Americans? Why?

Page | 155

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

3. What hypocrisies, if any, does Williams perceive among the Puritans in America? Why?

4. How does Williams’s view of the Puritans’ purpose and place in America differ from Bradford’s or Winthrop’s? Why?

5. What views does Williams express that foreshadow America’s post-Revolutionary separation of church and state?

2.6 CECIL CALVERT, LORD BALTIMORE

(1605–1675)

From his father George Calvert, Cecil Calvert inherited the title of Lord Baltimore and the charter from King Charles I to establish a colony at the Province of Maryland, comprising ten to twelve million acres of land in what is now the state of Maryland. Calvert governed the colony from England, sending his Instructions to the Colonists by Lord Baltimore to his brother Leonard, who served as the colony’s first governor. Calvert’s instructions served as the foundation for Maryland’s laws.

Throughout his proprietorship, Cecil Calvert fostered religious tolerance in the colony of Maryland. After Leonard’s death, Calvert commissioned a Protestant, William Stone, to serve as governor. He gave Stone a new law to be voted on by the Maryland Assembly, a law that came to be known as the Act of Toleration. This new law allowed colonists freedom of worship in any Christian faith, provided they maintained loyalty to Cecil Calvert and Maryland’s government.

2.6.1 From A Relation of the Lord Baltemore’s Plantation

in Maryland

Chapter I

His most Excellent Majestie having by his Letters Patent, under the Great Seale of England, granted a certaine Countrey in America (now called Maryland, in honour of our gratious Queene) unto the Lord Baltemore, with divers Priviledges, and encouragements to all those that should adventure with his Lordship in the Planting of that Countrey: the benefit and honour of such an action was readily apprehended by divers Gentlemen, of good birth and qualitie, who thereupon resolved to adventure their Persons, and a good part of their fortunes with his Lordship, in the pursuite of so noble and (in all likelihood) so advantagious an enterprize. His Lordship was at first resolved to goe in person; but the more important reasons perswading his stay at home, hee appointed his brother, Mr. Leonard Caluert to goe Governour in his stead, with whom he joyned in Commission, Mr.

Jerome Hawley, and Mr. Thomas Cornwallis (two worthy and able Gentlemen.) These with the other Gentlemen adventurers, and their servants to the number of neere 200. people, imbarked theselves for the voyage, in the good ship called the Arke, of 300. tunne & upward, which was attended by his Lordships Pinnace, Page | 156

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

called the Dove, of about 50. tunne. And so on Friday, the 22. of November, 1633.

a small gale of winde coming gently from the Northwest, they weighed from the Cowes in the Isle of Wight, about ten in the morning; And having stayed by the way Twenty dayes at the Barbada’s, and Fourteene dayes at Saint Christophers (upon some necessary occasions) they arrived at Point Comfort in Virginia, on the foure

& twentyeth of February following. They had Letters from his Majesty, in favor of them, to the Governour of Virginia, in obedience whereunto, he used them with much courtesie and humanitie. At this time, one Captaine Cleyborne (one of the Councel of Virginia) comming from the parts whether they intended to goe, told them that all the Natives were in preparation of defence by reason of a rumor some had raised amongst them, that 6. shippes were to come with many people, who would drive all the inhabitants out of the Countrey.

On the 3. of March, they left Point-Comfort, & 2. dayes after, they came to Patowmeck river, which is about 24. leagues distant, there they began to give names to places, and called the Southerne point of that River, Saint Gregories; and the Northerne point, Saint Michaels.

They sayled up the River, till they came to Heron Island, which is about 14.

leagues, and there came to an Anchor under an Island neere unto it, which they called S. Clements. Where they set up a Crosse, and tooke possession of this Countrey for our Saviour, and for our Soveraigne Lord the King of England.

Heere the Governor thought fit for the ship to stay, untill hee had discovered more of the Countrey: and so hee tooke two Pinnaces, and went up the River some 4. leagues, and landed on the South side, where he found the Indians fled for feare, from thence hee sayled some 9. leagues higher to Patowmeck Towne where the Werowance being a child, Archibau his unckle (who governed him and his Countrey for him) gave all the company good wellcome, and one of the company having entered into a little discourse with him, touching the errours of their religion, hee seemed well pleased therewith; and at his going away, desired him to returne thither againe, saying he should live with him, his men should hunt for him, and hee would divide all with him.

From hence the Governor went to Paschatoway, about 20. leagues higher, where he found many Indians assembled, and heere he met with one Captaine Henry Fleete an English-man, who had lived many yeeres among the Indians, and by that meanes spake the Countrey language very well, and was much esteemed of by the natives. Him our Governour sent a shore to invite the Werowance to a parley, who thereupon came with him aboard privatly, where he was courteously entertained, and after some parley being demanded by the Governour, whether hee would be content that he and his people should set downe in his Countrey, in case he should find a place convenient for him, his answere was, “that he would not bid him goe, neither would hee bid him stay, but that he might use his owne discretion. ”

While this Werowance was aboard, many of his people came to the water side, fearing that he might be surprised, whereupon the Werowance commanded two Indians that came with him, to goe on shore, to quit them of this feare, but they Page | 157

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

answered, they feared they would kill them; The Werowance therefore shewed himselfe upon the decke, and told them hee was in safety, wherewith they were satisfied.

Whilest the Governour was abroad, the neighbouring Indians, where the ship lay, began to cast off feare, and to come to their Court of guard, which they kept night and day upon Saint Clements Ile, partly to defend their barge, which was brought in pieces out of England, and there made up; and partly to defend their men which were imployed in felling of trees, and cleaving pales for a Palizado, and at last they ventured to come aboard the ship.

The Governour finding it not fit, for many reasons, to seate himselfe as yet so high in the River, resolved to returne backe againe, and to take a more exact view of the lower part, and so leaving the Ship & Pinnaces there, he tooke his Barge (as most fit to search the Creekes, and small rivers) and was conducted by Captaine Fleete (who knew well the Countrey) to a River on the North-side of Patomeck river, within 4. or 5. leagues from the mouth thereof, which they called Saint Georges River. They went up this river about 4. Leagues, and anchored at the Towne of Yoacomaco: from whence the Indians of that part of the Countrey, are called Yoacomacoes:

At their comming to this place, the Governour went on shoare, and treated friendly with the Werowance there, and acquainted him with the intent of his comming thither, to which hee made little answere (as it is their manner, to any new or suddaine question) but entertained him, and his company that night in his house, and gave him his owne bed to lie on (which is a matt layd on boords) and the next day, went to shew him the country, and that day being spent in viewing the places about that towne, and the fresh waters, which there are very plentifull and excellent good (but the maine rivers are salt) the Governor determined to make the first Colony there, and so gave order for the Ship and Pinnaces to come thither.

This place he found to be a very commodious situation for a Towne, in regard the land is good, the ayre wholsome and pleasant, the River affords a safe harbour for ships of any burthen, and a very bould shoare; fresh water, and wood there is in great plenty, and the place so naturally fortified, as with little difficultie, it will be defended from any enemie.

To make his entry peaceable and safe, hee thought fit to present the Werowance and the Wisoes of the Towne with some English Cloth, (such as is used in trade with the Indians) Axes, Howes, and Knives, which they accepted very kindly, and freely gave consent that hee and his company should dwell in one part of their Towne, and reserved the other for themselves; and those Indians that dwelt in that part of the Towne, which was allotted for the English, freely left them their houses, and some corne that they had begun to plant: It was also agreed between them, that at the end of harvest they should leave the whole towne; which they did accordingly: And they made mutuall promises to each other, to live friendly and peaceably together, and if any injury should happen to be done on any part, that satisfaction should be made for the same, and thus upon the 27. day of March, Page | 158

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Anno Domini, 1634. the Governour tooke possession of the place, and named the Towne Saint Maries.

There was an occasion that much facilitated their treaty with these Indians, which was this: The Sasquehanocks (a warlike people that inhabite betweene Chesopeack bay, and Delaware bay) did usually make warres, and incursions upon the neighbouring Indians, partly for superiority, partly for to get their Women, and what other purchase they could meet with, which these Indians of Yocomaco fearing, had the yeere before our arivall there, made a resolution, for their safety, to remove themselves higher into the Countrey where it was more populous, and many of them were gone thither before the English arrived.

Three dayes after their comming to Yoacomaco the Arke with the two Pinaces arived there. The Indians much wondred to see such ships, and at the thundering of the Ordnance when they came to an Anchor.

The next day they began to prepare for their houses, and first of all a Court of Guard, and a Store-house; in the meane time they lay abord the ship: They had not beene there many dayes before Sir John Haruie the governor of Virginea came thither to visit them: Also some Indian Werowances, and many other Indians from severall parts came to see them, amongst others the Werowance of Patuxent came to visit the Governour, and being brought into the great Cabin of the ship, was placed betweene the Governour of Virginea, and the Governour of Mary-land; and a Patuxent Indian that came with him, comming into the Cabin, and finding the Werowance thus sitting betweene the two Governours, started backe, fearing the Werowance was surprised, and was ready to have leapt overboard, and could not be perswaded to come into the Cabin, untill the Werowance came himselfe unto him; for he remembered how the said Werowance had formerly beene taken prisoner by the English of Virginia.

After they had finished the store-house, and unladed the ship, the Governour thought fit to bring the Colours on shore, which were attended by all the Gentlemen, and the rest of the servants in armes; who received the Colours with a volley of shot, which was answered by the Ordnance from the ships; At this Ceremony were present, the Werowances of Patuxent, and Yoacomaco, with many other Indians; and the Werowance of Patuxent hereupon tooke occasion to advise the Indians of Yoacomaco to be carefull to keepe the league that they had made with the English.

He stayed with them divers dayes, and used many Indian Complements, and at his departure hee said to the Governour. “I love the English so well, that if they should goe about to kill me, if I had but so much breath as to speake; I would command the people, not to revenge my death; for I know they would not doe such a thing, except it were through mine owne default.”

They brought thither with them some store of Indian Corne, from the Barbado’s, which at their first arivall they began to use (thinking fit to reserve their English provision of Meale and Oatemeale) and the Indian women seeing their servants to bee unacquainted with the manner of dressing it, would make bread thereof for them, and teach them how to doe the like: They found also the countrey well stored Page | 159

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

with Corne (which they bought with truck, such as there is desired, the Natives having no knowledge of the use of money) whereof they sold them such plenty, as that they sent 1,000. bushells of it to New-England, to provide them some salt-fish, and other commodities which they wanted.

During the time that the Indians stai’d by the English at Yoacomaco, they went dayly to hunt with them for Deere and Turkies, whereof some they gave them for Presents, and the meaner sort would sell them to them, for knives, beades and the like: Also of Fish, the natives brought them great store, and in all things dealt very friendly with them; their women and children came very frequently amongst them, which was a certaine signe of their confidence of them, it being found by experience, that they never attempt any ill, where the women are, or may be in danger.

Their comming thus to feate upon an Indian Towne, where they found ground cleered to their hands, gave them opportunity (although they came late in the yeere) to plant some Corne, and to make them gardens, which they sowed with English seeds of all sorts, and they prospered exceeding well. They also made what haste they could to finish their houses; but before they could accomplish all these things, one Captaine Cleyborne (who had a desire to appropriate the trade of those parts unto himselfe) began to cast out words amongst the Indians, saying, That those of Yoacomaco were Spaniards and his enemies; and by this meanes endeavoured to alienate the mindes of the Natives from them, so that they did not receive them so friendly as formerly they had done. This caused them to lay aside all other workes, and to finish their Fort, which they did within the space of one moneth; where they mounted some Ordnance, and furnished it with some murtherers, and such other meanes of defence as they thought fit for their safeties: which being done, they proceeded with their Houses and finished them, with convenient accommodations belonging thereto: And although they had thus put themselves in safety, yet they ceased not to procure to put these jealousies out of the Natives minds, by treating and using them in the most courteous manner they could, and at last prevailed therein, and setled a very firme peace and friendship with them. They procured from Virginia, Hogges, Poultrey, and some Cowes, and some male cattell, which hath given them a foundation for breed and increase; and whoso desires it, may furnish himselfe with store of Cattell from thence, but the hogges and Poultrey are already increased in Maryland, to a great stocke, sufficient to serve the Colonie very plentifully. They have also set up a Water-mill

for the grinding of Corne, adjoyning to the Towne.

Thus within the space of fixe moneths, was laid the foundation of the Colonie in Maryland; and whosoever intends now to goe thither, shall finde the way so troden, that hee may proceed with much more ease and confidence then these first adventurers could, who were ignorant both of Place, People, and all things else, and could expect to find nothing but what nature produced: besides, they could not in reason but thinke, the Natives would oppose them; whereas now the Countrey is is discovered, and friendship with the natives is assured, houses built, and many other accommodations, as Cattell, Hogges, Poultry, Fruits and the like Page | 160

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

brought thither from England, Virginea, and other places, which are usefull, both for profit and Pleasure: and without boasting it may be said, that this Colony hath arived to more in fixe moneths, then Virginia did in as many yeeres. If any man say, they are beholding to Virginea for so speedy a supply of many of those things which they of Virginia were forced to fetch from England and other remote places, they will confesse it, and acknowledge themselves glad that Virginea is so neere a neighbour, and that it is so well stored of all necessaries for to make those parts happy, and the people to live as plentifully as in any other part of the world, only they wish that they would be content their neighbours might live in peace by them, and then no doubt they should find a great comfort each in other.

Chapter III

The Commodities which this Countrey affords naturally.

This Countrey affords naturally, many excellent things for Physicke and Surgery, the perfect use of which, the English cannot yet learne from the Natives: They have a roote which is an excellent preservative against Poylon, called by the English, the Snake roote. Other herbes and rootes they have, wherewith they cure all manner of woundes; also Saxafras, Gummes, and Balfum. An Indian seeing one of the English, much troubled with the tooth-ake, fetched of the roote of a tree, and gave the party some of it to hold in his mouth, and it eased the paine presently. They have other rootes fit for dyes, wherewith they make colours to paint themselves.

The Timber of these parts is very good, and in aboundance, it is usefull for building of houses, and shippes; the white Oake is good for Pipe-staves, the red Oake for wainescot. There is also Walnut, Cedar, Pine, & Cipresse, Chesnut, Elme, Ashe, and Popler, all which are for Building, and Husbandry. Also there are divers sorts of Fruit-trees, as Mulberries, Persimons, with severall other kind of Plummes, and Vines, in great aboundance. The Mast and the Chesnuts, and what rootes they find in the woods, doe feede the Swine very fat, and will breede great store, both for their owne provision, or for merchandise, and such as is not inferior to the Bacon of Westphalia.

Of Strawberries, there is plenty, which are ripe in Aprill: Mulberries in May; and Raspices in June; Maracocks which is somewhat like a Limon, are ripe in August.

In the Spring, there are severall sorts of herbes, as Corn-fallet, Violets, Sorrell, Purflaine, all which are very good and wholsome, and by the English, used for sallets, and in broth.

In the upper parts of the Countrey, there are Bufeloes, Elkes, Lions, Beares, Wolues, and Deare there are in great store, in all places that are not too much frequented, as also Beavers, Foxes, Otters, and many other sorts of Beasts.

Of Birds, there is the Eagle, Goshawke, Falcon, Lanner, Sparrow-hawke, and Merlin, also wild Turkeys in great aboundance, whereof many weigh 50. pounds, Page | 161

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

and upwards; and of Partridge plenty: There are likewise sundry sorts of Birds which sing, whereof some are red, some blew, others blacke and yellow, some like our Black-birds, others like Thrushes, but not of the same kind, with many more, for which wee know no names.

In Winter there is great plenty of Swannes, Cranes, Geese, Herons, Ducke, Teale, Widgeon, Brants, and Pidgeons, with other sorts, whereof there are none in England.

The Sea, the Bayes of Chesopeack, and Delaware, and generally all the Rivers, doe abound with Fish of severall sorts; for many of them we have no English names: There are Whales, Sturgeons very large and good, and in great aboundance; Grampuses, Porpuses, Mullets, Trouts, Soules, Place, Mackerell, Perch, Crabs, Oysters, Cockles, and Mussles; But above all these, the fish that have no English names, are the best except the Sturgeons: There is also a fish like the Thornebacke in England, which hath a taile a yard long, wherein are sharpe prickles, with which if it strike a man, it will put him to much paine and torment, but it is very good meate: also the Todefish, which will swell till it be ready to burst, if it be taken out of the water.

The Mineralls have not yet beene much searched after, yet there is discovered Iron Oare; and Earth fitt to make Allum, Terra lemnia, and a red soile like Bolearmonicke, with sundry other sorts of Mineralls, which wee have not yet beene able to make any tryall of.

The soile generally is very rich, like that which is about Cheesweeke neere London, where it is worth 20. shillings an Acre yeerely to Tillage in the Common-fields, and in very many places, you shall have two foote of blacke rich mould, wherein you shall scarce find a stone, it is like a sifted Garden-mould, and is so rich that if it be not first planted with Indian corne, Tobacco, Hempe, or some such thing that may take off the ranknesse thereof, it will not be fit for any English graine; and under that, there is found good loame, where-of wee have made as good bricke as any in England; there is great store of Marish ground also, that with good husbandry, will make as rich Medow, as any in the world: There is store of Marie, both blue, and white, and in many places, excellent clay for pots, and tyles; and to conclude, there is nothing that can be reasonably expected in a place lying in the latitude which this doth, but you shall either find it here to grow naturally: or Industry, and good husbandry will produce it.

Chapter IIII

The commodities that may be procured in Maryland by industry.

Hee that well considers the situation of this Countrey, and findes it placed betweene Virginia and New-England, cannot but, by his owne reason, conclude that it must needs participate of the naturall commodities of both places, and be capable of those which industry brings into either, the distances being so small betweene them: you (hall find in the Southerne parts of Maryland, all that Virginia hath naturally; and in the Northerne parts, what New-England produceth: and he Page | 162

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

that reades Captaine John Smith shall see at large discoursed what is in Virginia, and in Master William Wood, who this yeere hath written a treatise of New-England, he may know what is there to be expected.

Yet to say something of it in particular.

In the first place I name Corne, as the thing most necessary to sustaine man; That which the Natives use in the Countrey, makes very good bread, and also a meate which they call Omene, it’s like our Furmety, and is very savory and wholesome; it will Mault and make good Beere; Also the Natives have a sort of Pulse, which we call Pease and Beanes, that are very good. This Corne yeelds a great increase, so doth the Pease and Beanes: One man may in a season, well plant so much as will yeeld a hundred bustiells of this Corne, 20 bushells of Beanes and Pease, and yet attend a crop of Tobacco: which according to the goodnesse of the ground may be more or lesse, but is ordinarily accompted betweene 800 and 100 pound weight.

They have made tryall of English Pease, and they grow very well, also Muskmellons, Water-melons, Cow-cumbers, with all sorts of garden Roots and Herbes, as Carrots, Parsenips, Turnips, Cabbages, Radish with many more; and in Virginia they have sowed English Wheate and Barley, and it yeelds twise as much increase as in England; and although there be not many that doe apply themselves to plant Gardens and Orchards, yet those that doe it, find much profit and pleasure thereby: They have Peares, Apples, and severall forts of Plummes, Peaches in abundance, and as good as those of Italy; so are the Mellons and Pumpions: Apricocks, Figgs and Pomegranates prosper exceedingly; they have lately planted Orange and Limon trees which thrive very wel: and in fine, there is scarce any fruit that growes in England, France, Spaine or Italy, but hath been tryed there, and prospers well.

You may there also have hemp and Flax, Pitch and Tarre, with little labour; it’s apt for Rapefeed, and Annis-seed, Woad, Madder, Saffron, &c. There may be had, Silke-wormes, the Countrey being stored with Mulberries: and the superfluity of wood will produce Potashes.

And for Wine, there is no doubt but it will be made there in plenty, for the ground doth naturally bring foorth Vines, in such aboundance, that they are as frequent there, as Brambles are here. Iron may be made there with little charge; Brave ships may be built, without requiring any materials from other parts: Clabboard, Wainscott, Pipe-staves and Masts for mips the woods will afford plentifully. In fine, Butter and Cheese, Porke and Bacon, to transport to other countrys will be no small commodity, which by industry may be quickly had there in great plenty,

&c. And if there were no other staple commodities to be hoped for, but Silke and Linnen (the materialls of which, apparantly will grow there) it were sufficient to enrich the inhabitants.

Chapter V

Of the Naturall disposition of the Indians which Inhabite the parts of Maryland where the English are seated: And their manner of living.

Page | 163

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Hee that hath a Curiosity to know all that hath beene observed of the Customes and manners of the Indians, may find large discourses thereof in Captaine Smiths Booke of Virginia, and Mr. Woods of New-England: but he that is desirous to goe to Maryland, shall here find enough to informe him of what is necessary for him to know touching them. By Captaine Smith’s, and many other Relations you may be informed, that the People are War-licke, and have done much harme to the English; and thereby are made very terrible. Others say that they are a base and cowardly People, and to be contemned: and it is thought by some who would be esteemed States-men, that the only point of pollicie that the English can use, is, to destroy the Indians, or to drive them out of the Countrey, without which, it is not to be hoped that they can be secure. The truth is, if they be injured, they may well be feared, they being People that have able bodies, and generally, taller, and bigger limbed then the English, and want not courage; but the oddes wee have of them in our weapons, keepes them in awe, otherwise they would not flie from the English, as they have done in the time of Warres with those of Virginia, and out of that respect, a small number of our men being armed, will adventure upon a great troope of theirs, and for no other reason, for they are resolute and subtile enough: But from hence to conclude, that there can be no safety to live with them, is a very great errour. Experience hath taught us, that by kind and faire usage, the Natives are not onely become peaceable, but also friendly, and have upon all occasions performed as many friendly Offices to the English in Maryland, and New-England, as any neighbour or friend uses to doe in the most Civill parts of Christendome: Therefore any wise man will hold it a far more just and reasonable way to treat the People of the Countrey well, thereby to induce them to civility, and to teach them the use of husbandry, and Mechanick trades, whereof they are capable, which may in time be very usefull to the English; and the Planters to keepe themselves strong, and united in Townes, at least for a competent number, and then noe man can reasonably doubt, either surprise, or any other ill dealing from them.

But to proceede, hee that sees them, may know how men lived whilest the world was under the Law of Nature; and, as by nature, so amongst them, all men are free, but yet subject to command for the publike defence. Their Government is Monarchicall, he that governes in chiefe, is called the Werowance, and is assisted by some that consult with him of the common affaires, who are called Wisoes: They have no Lawes, but the Law of Nature and discretion, by which all things are ruled, onely Custome hath introduced a law for the Succession of the Government, which is this; when a Werowance dieth, his eldest sonne succeeds, and after him the second, and so the rest, each for their Hues, and when all the sonnes are dead, then the sons of the Werowances eldest daughter shall succeede, and so if he have more daughters; for they hold, that the issue of the daughters hath more of his blood in them than the issue of his sonnes. The Wisoes are chosen at the pleasure of the Werowance, yet commonly they are chosen of the same family, if they be of yeeres capable: The yong men generally beare a very great respect to the elder.

Page | 164

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

They have also Cockorooses that are their Captains in time of war, to whom they are very obedient: But the Werowance himselfe plants Corne, makes his owne Bow and Arrowes, his Canoo, his Mantle, Shooes, and what ever else belongs unto him, as any other common Indian; and commonly the Commanders are the best and most ingenious and active in all those things which are in esteeme amongst them. The woman serve their husbands, make their bread, dresse their meate, such as they kill in hunting, or get by fishing; and if they have more wives than one, as some of them have (but that is not generall) then the best beloved wife performes all the offices of the house, and they take great content therein. The women also (beside the houshold businesse) use to make Matts, which serve to cover their houses, and for beds; also they make baskets, some of Rushes, others of Silke-grasse, which are very handsom.

The Children live with their Parents; the Boyes untill they come to the full growth of men; (for they reckon not by yeeres, as we doe) then they are put into the number of Bow-men, and are called Blacke-boyes (and so continue until they take them wives) When they are to be made Black-boyes, the ancient men that governe the yonger, tell them, That if they will be valiant and obedient to the Werowance, Wisos, and Cockorooses, then their god will love them, all men will esteeme of them, and they shall kill Deere, and Turkies, catch Fish, and all things shall goe well with them; but if otherwise, then shall all goe contrary: which perswasion mooves in them an incredible obedience to their commands; If they bid them take fire in their hands or mouthes, they will doe it, or any other desperate thing, although with the apparant danger of their lives.

The woman remaine with their Parents until they have huasonds, and if the Parents bee dead, then with some other of their friends. If the husband die, he leaves all that he hath to his wife, except his bow and arrowes, and some Beades (which they usually bury with them) and she is to keepe the children untill the sons come to be men, and then they live where they please, for all mens houses are free unto them; and the daughters untill they have husbands. The manner of their marriages is thus; he that would have a wife, treates with the father, or if he be dead, with the friend that take care of her whom he desires to have to wife, and agrees with him for a quantity of Beades, or some such other thing which is accepted amongst them; which he is to give for her, and must be payed at the day of their marriage; and then the day being appointed, all the friends of both parts meet at the mans house that is to have the wife, and each one brings a present of meate, and the woman that is to be married also brings her present: when the company is all come, the man he sits at the upper end of the house, and the womans friends leade her up, and place her by him, then all the company sit down upon mats, on the ground (as their manner is) and the woman riseth and serves dinner, First to her husband, then to all the company the rest of the day they spend in singing and dancing (which is not unpleasant) at night the company leaves the, and comonly they live very peaceably and lovingly together; Yet it falls out sometimes, that a man puts away one wife and takes another: then she and her children returne to Page | 165

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

her friends again. They are generally very obedient to their husbands, and you shal seldome heare a woman speake in the presence of her husband, except he aske her some question.

This people live to a great age, which appeares, in that although they marry not so yong as we doe in England, yet you may see many of them great-grandfathers to children of good bignesse; and continue at that age, very able and strong men: The Men and Women have all blacke haire, which is much bigger and harsher then ours, it is rare to see any of them to waxe gray, although they be very old, but never bauld: It is seldome seene that any of the men have beards, but they weare long locks, which reach to their shoulders, and some of them to their wasts: they are of a comely stature, well favoured, and excellently well limbed, and seldome any deformed. In their warres, and hunting, they use Bowes and Arrowes (but the Arrowes are not poysoned, as in other places.) The Arrow-heads are made of a Flint-stone, the top of a Deares horn, or some Fish-bone, which they fasten with a sort of glew, which they make. They also use in warres, a short club of a cubite long, which they call a Tomahawk.

They live for the most part in Townes, like Countrey Villages in England; Their houses are made like our Arboures, covered some with matts, others with barke of trees, which defend them from the injury of the weather: The fiers are in the midst of the house, and a hole in the top for the smoake to goe out at. In length, some of them are 30. others 40. some a 100. foote; and in breadth about 12. foote. They have some things amongst them which may well become Christians to imitate, as their temperance in eating and drinking, their Justice each to other, for it is never heard of, that those of a Nation will rob or steale one from another; and the English doe often trust them with truck, to deale for them as factors, and they have performed it very justly: Also they have sent letters by them to Virginia, and into other parts of of the Countrey, unto their servants that have beene trading abroad, and they have delivered them, and brought backe answere thereof unto those that sent thfcm; Also their conuersation each with other, is peaceable, and free from all scurrulous words, which may give offence; They are very hospitable to their owne people, and to strangers ; they are also of a grave comportment: Some of the Adventurers at a time, was at one of their feasts, when Two hundred of them did meet together; they eate of but one dish at a meale, and every man, although there be never so many, is serued in a dish by himselfe; their dishes are made of wood, but handsomely wrought; The dinner lasted two houres; and after dinner, they sung and danced about two houres more, in all which time, not one word or action past amongst them that could give the least disturbance to the company; In the most grave assembly, no man can expect to find so much time past with more silence and gravitie: Some Indians comming on a time to James Towne in Virginia, it happened, that there then fate the Councell to heare causes, and the Indians feeing such an assembly, asked what it meant? Answere was made, there was held a Match-comaco (which the Indians call their place of Councell) the Indian replyed, that they all talke at once, but wee doe not so in our Match-comaco.

Page | 166

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Their attire is decent and modest; about their wasts, they weare a covering of Deares skinnes, which reacheth to their knees, and upon their shoulders a large mantle of skinnes, which comes downe to the middle of the legge, and some to the heele; in winter they weare it furred, in summer without; When men hunt they put off their Mantles, so doe the women when they worke, if the weather be hot: The women affect to weare chaines and bracelets of beades, some of the better sort of them, weare ropes of Pearle about their necks, and some hanging in their eares, which are of a large sort, but spoyled with burning the Oysters in the fire, and the rude boaring of them. And they and the young men use to paint their faces with severall colours, but since the English came thither, those about them have quite left it; and in many things (hew a great inclination to conforme themselues to the English manner of living. The Werowance of Paschatoway desired the Governor to send him a man that could build him a house like the English, and in sundry respects, commended our manner of living, as much better then their owne: The Werowance of Patuxent, goes frequently in English Attire, so doth he of Portoback, and many others that have bought Clothes of the English: These Werowances have made request, that some of their children may be brought up amongst the English, and every way, shew great demonstrations of friendship, and good affection unto them.

These People acknowledge a God, who is the giver of al the good things, wherewith their life is maintained; and to him they sacrifice of the first fruits of their Corne, and of that which they get by hunting and fishing: The sacrifice is performed by an Ancient man, who makes a speech unto their God (not without something of Barbarisme) which being ended, hee burnes part of the sacrifice, and then eates of the rest, then the People that are present, eate also, and untill the Ceremony be performed, they will not touch one bit thereof: They hold the Immortalitie of the soule, and that there is a place of Joy, and another of torment after death, and that those which kill, steale, or lye, shall goe to the place of torment, but those which doe no harme, to the good place; where they shall have all sorts of pleasure.

It happened the last yeere, that some of the Sasquehanocks and the Wicomesses (who are enemies) met at the Hand of Monoponson, where Captaine Cleyborne liveth, they all came to trade, and one of the Sasquehanocks did an Injury to a Wicomesse, whereat some of Cleybornes people that saw it, did laugh.

The Wicomesses seeing themselves thus injured and despised (as they thought) went away, and lay in ambush for the returne of the Sasquehanocks, and killed five of them, onely two escaped; and then they returned againe, and killed three of Cleybornes People, and some of his Cattle; about two moneths after this was done, the Wicomesses sent a messenger unto his Lordships Governor, to excuse the fact, and to offer satisfaction for the harme that was done to the English: The Wicomesse that came with the message, brought in his company an Indian, of the Towne of Patuxent, which is the next neighbouring Towne unto the English at Saint Maries, with whom they have good correspondence, and hee spake to the Governour in this manner.

Page | 167

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

I am a Native of Patuxent, as this man (whom you know) can tell you, true it is, I married a wife amongst the Wicomesses, where I have lived ever since, and they have sent me to tell you, that they are sorry for the harme, which was lately done by some of their people, to the English at Monaponson; and hope you will not make the rash act of a few young men (which was done in heate) a quarrell to their Nation, who desire to live in peace and love with you, and are ready to make satisfaction for the Injury, desiring to know what will give you content, and that they will returne such things as were then taken from thence; But withall, they desire you not to thinke that they doe this for feare, for they have warres with the Sasquehanocks, who have by a surprise, lately killed many of their men, but they would not sue to them for peace, intending to revenge the injuries, as they could find opportunitie, yet their desire was to have peace with the English.

The Governour returned answere to the Wicomesse ;since you acknowledge the Injury, and are sorry for it, and onely desire to know what I expect for satisfaction; I tell you I expect that those men, who have done this out-rage, should be delivered unto me, to do with them as I shall thinke fit, and likewise that you restore all such things as you then tooke from the English; and withall, charged him with a second Injury attempted upon some of his owne People, since that time, by the Wicomesses.

The Wicomesse after a little pause, replyed; It is the manner amongst us Indians, that if any such like accident happen, wee doe redeeme the life of a man that is so slaine, with a 100. armes length of Roanoke (which is a sort of Beades that they make, and use for money) and since that you are heere strangers, and come into our Countrey, you should rather conforme your selves to the Customes of our Countrey, then impose yours upon us; But as for the second matter, I know nothing of it, nor can give any answere thereunto.

The Governour then told him; It seemes you come not sufficiently instructed in the businesse which wee have with the Wicomesses, therefore tell them what I have said; and that I expect a speedy answere; and so dismist him.

It fell in the way of my discourse, to speake of the Indian money of those parts, It is of two sorts, Wompompeag and Roanoake; both of them are made of a fish-shell, that they gather by the Sea side, Wompompeag is of the greater sort, and Roanoake of the lesser, and the Wompompeag is three times the value of Roanoake; and these serve as Gold and Silver doe heere; they barter also one commoditie for another, and are very glad of trafficke and commerce, so farre as to supply their necessities: They shew no great desire of heaping wealth, yet some they will have to be buryed with them; If they were Christians, and would live so free from covetousnesse, and many other vices, which abound in Christendome, they would be a brave people.

I therefore conclude, that since God Almighty hath made this Countrey so large and fruitfull, and that the people be such as you have heard them described; Page | 168

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

It is much more Prudence, and Charity, to Civilize, and make them Christians, then to kill, robbe, and hunt them from place to place, as you would doe a wolfe.

By reducing of them, God shall be served, his Majesties Empire enlarged by the addition of many thousand Subjects, as well as of large Territories, our Nation honoured, and the Planters themselves enriched by the trafficke and commerce which may be had with them; and in many other things, they may be usefull, but presudiciall they cannot be, if it be not through their owne faults, by negligence of fortifying themselves, and not consering military discipline.

2.6.2 Reading and Review Questions

1. What, if any, significance do you see in the voyagers on the Dove and the Arke hearing as soon as they arrived at the Patowmeck river that (a) hostile American Indians were gathering against them, and (b) they raised a cross on the island of S. Clements, taking possession of

“this Countrey for our Saviour, and for our Soveraigne Lord the King of England?”

2. How does the experience of these colonizers compare with those at Jamestown or Plymouth Plantation? Why? How does the purpose of these colonizers differ from earlier groups?

3. Why does Calvert make such a point about the approval and support these colonizers gained from the start from the Native Americans? What evidence does he give?

4. What values, in terms of material wealth and prosperity, are apparent in Calvert’s account of the commodities procurable through industry? How do these values compare to those of other colonizers?

5. How much attention does Calvert give to gender issues among the American Indians? Why? What is his attitude towards American Indian women? How do you know? How does his description of gender issues differ from those of other accounts, like van der Donck’s or Champlain’s?

2.7 ANNE BRADSTREET

(1612–1672)

Like many women of her era, Anne Bradstreet’s life quite literally depended upon those of her male relatives. In Bradstreet’s case, these relatives were her father, Thomas Dudley (1576–1653), and her husband Simon Bradstreet (1603–1697). Her father encouraged Bradstreet’s literary bent; her husband caused her emigration from England to America. Both guided her Puritan faith. She met Simon Bradstreet through his and her father’s working for the estate of the Earl of Lincoln (1600–

1667), a Puritan. Simon Bradstreet helped form the Massachusetts Bay Company.

With him, Anne Bradstreet sailed on the Arbella to become a member of that colony.

Page | 169

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Despite this dependence, Bradstreet showed

independence of mind and spirit quite remark-

able for a woman of her era. She felt that the Bible

was not fulfilling the religious enlightenment

and transcendence she sought. In America, she

eventually saw firsthand, so to speak, the hand of

the God to whom she would devote herself. Even

as she fulfilled a woman’s “appointed” domestic

role and duties as wife and mother, Bradstreet

realized her individual voice and vision through

the poetry she wrote from her childhood on. Her

poetic ambitions appear through the complex

poetic forms in which she wrote, including

rhymed discourses and “Quaternions,” or four-

part poems focusing on four topics of fours: the

four elements, the four humors, the four ages of

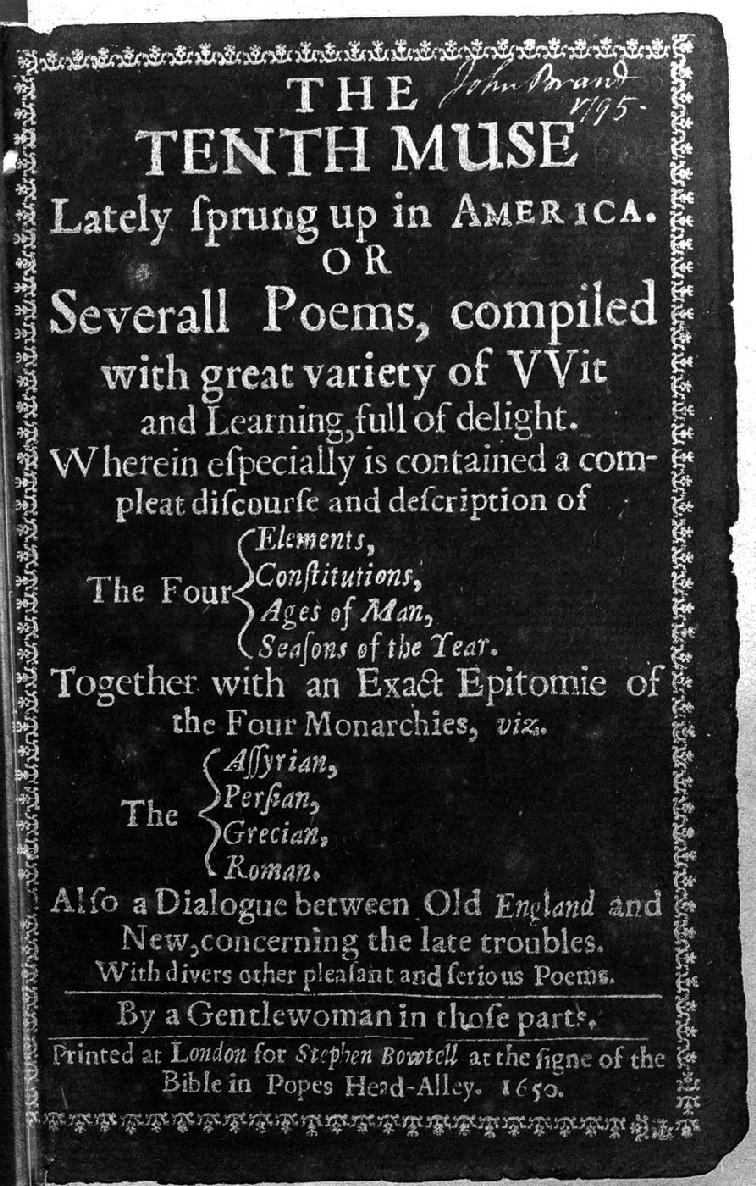

man, and the four seasons. Her ambitions show Image 2.6 | “The Tenth Muse”

also in the poets whose work she emulated or Author | Anne Bradstreet learned from, poets including Sir Philip Sidney Source | Wikimedia Commons License | Public Domain

(1554–1586), Edmund Spenser (1552–1599),

and John Donne (1572–1631).

Her ambition may not have been to publish her work. It was due to another male relative, her brother-in-law John Woodbridge (1613–1696), that her manuscript of poems was published. He brought the manuscript with him to London where it was published in 1651 as The Tenth Muse Lately Spring Up in America, By a Gentlewoman of Those Parts. The first book of poetry published by an American, it gained strong notice in England and Europe.

These poems use allusion and er-

udition to characterize Bradstreet’s

unique, “womanly” voice. Poems

later added to this book, some

after her death, augment this voice

through their simplicity and their

attention to the concrete details

of daily life. With personal lyri-

cism, these poems give voice to

Bradstreet’s meditations on God and

Image 2.7 | Etching of a House from The Works

God’s trials—such as her own illness,

of Anne Bradstreet in Prose and Verse

the burning of her house, and the

Artist | Unknown

deaths of grandchildren—as well as

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

God’s gifts, such as marital love.

Page | 170

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

2.7.1 “The Prologue”

I

To sing of Wars, of Captains, and of Kings,

Of Cities founded, Common-wealths begun,

For my mean pen are too superior things:

Or how they all, or each their dates have run

Let Poets and Historians set these forth,

My obscure Lines shall not so dim their worth.

II

But when my wondring eyes and envious heart

Great Bartas sugar’d lines, do but read o’re

Fool I do grudge the Muses did not part

‘Twixt him and me that overfluent store,

A Bartas can, do what a Bartas will

But simple I according to my skill.

III

From school-boyes tongue no rhet’rick we expect

Nor yet a sweet Consort from broken strings,

Nor perfect beauty, where’s a main defect:

My foolish, broken blemish’d Muse so sings

And this to mend, alas, no Art is able,

‘Cause nature, made it so irreparable.

IV

Nor can I, like that fluent sweet-tongu’d Greek,

Who lisp’d at first, in future times speak plain

By Art he gladly found what he did seek

A full requital of his, striving pain

Art can do much, but this maxime’s most sure

A weak or wounded brain admits no cure.

V

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue

Who says my hand a needle better fits.

A Poets pen all scorn I should thus wrong.

For such despite they cast on Female wits:

If what I do prove well, it won’t advance,

They’l say it’s stoln, or else it was by chance.

Page | 171

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

VI

But sure the Antique Greeks were far more mild,

Else of our Sexe why feigned they those Nine

And poesy made, Calliope’s own child;

So ‘mongst the rest they placed the Arts Divine:

But this weak knot, they will full soon untie,

The Greeks did nought, but play the fools & lye.

VII

Let Greeks be Greeks, and women what they are.

Men have precedency, and still excell.

It is but vain unjustly to wage warre,

Men can do best, and women know it well

Preheminence in all and each is yours;

Yet grant some small acknowledgement of ours.

VIII

And oh ye high flown quills that soar the Skies,

And ever with your prey still catch your praise,

If e’re you daigne these lowly lines your eyes

Give Thyme or Parsley wreath; I ask no bayes,

This mean and unrefined ore of mine

Will make you glistring gold, but more to shine:

2.7.2 “The Author to Her Book”

Thou ill-form’d offspring of my feeble brain,

Who after birth did’st by my side remain,

Till snatcht from thence by friends, less wise then true

Who thee abroad, expos’d to publick view,

Made thee in raggs, halting to th’ press to trudg,

Where errors were not lessened (all may judg)

At thy return my blushing was not small,

My rambling brat (in print) should mother call,

I cast thee by as one unfit for light,

Thy Visage was so irksome in my sight;

Yet being mine own, at length affection would

Thy blemishes amend, if so I could:

I wash’d thy face, but more defects I saw,

And rubbing off a spot, still made a flaw.

I stretcht thy joynts to make thee even feet,

Yet still thou run’st more hobling then is meet;

Page | 172

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

In better dress to trim thee was my mind,

But nought save home-spun Cloth, i’ th’ house I find

In this array, ‘mongst Vulgars mayst thou roam

In Criticks hands, beware thou dost not come;

And take thy way where yet thou art not known,

If for thy Father askt, say, thou hadst none:

And for thy Mother she alas is poor,

Which caus’d her thus to send thee out of door.

2.7.3 “To My Dear and Loving Husband”

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee,

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

I prize thy love more then whole Mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold,

My love is such that Rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee, give recompence.

Thy love is such I can no way repay,

The heavens reward thee manifold I pray.

Then while we live, in love lets so persever,

That when we live no more, we may live ever.

2.7.4 “Contemplations”

I

Sometime now past in the Autumnal Tide,

When Phœbus wanted but one hour to bed,

The trees all richly clad, yet void of pride,

Were gilded o’re by his rich golden head.

Their leaves & fruits seem’d painted, but was true

Of green, of red, of yellow, mixed hew,

Rapt were my sences at this delectable view.

II

I wist not what to wish, yet sure thought I,

If so much excellence abide below,

How excellent is he that dwells on high?

Whose power and beauty by his works we know.

Sure he is goodness, wisdome, glory, light,

That hath this under world so richly dight:

More Heaven then Earth was here, no winter & no night.

Page | 173

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

III

Then on a stately Oak I cast mine Eye,

Whose ruffling top the Clouds seem’d to aspire.

How long since thou wast in thine Infancy?

Thy strength, and stature, more thy years admire,

Hath hundred winters past since thou wast born,

Or thousand since thou brakest thy shell of horn,

If so, all these as nought, Eternity doth scorn.

IV

Then higher on the glistering Sun I gaz’d,

Whose beams was shaded by the leavie Tree.

The more I look’d, the more I grew amaz’d

And softly said, what glory’s like to thee?

Soul of this world, this Universes Eye,

No wonder, some made thee a Deity:

Had I not better known, (alas) the same had I.

V

Thou as a Bridegroom from thy Chamber rushes

And as a strong man, joyes to run a race,

The morn doth usher thee, with smiles & blushes.

The Earth reflects her glances in thy face.

Birds, insects, Animals with Vegative,

Thy heart from death and dulness doth revive;

And in the darksome womb of fruitful nature dive.

VI

Thy swift Annual, and diurnal Course,

Thy daily streight, and yearly oblique path,

Thy pleasing fervor, and thy scorching force,

All mortals here the feeling knowledg hath

Thy presence makes it day, thy absence night,

Quaternal Seasons caused by thy might:

Hail Creature, full of sweetness, beauty & delight.

VII

Art thou so full of glory, that no Eye

Hath strength, thy shining Rayes once to behold?

And is thy splendid Throne erect so high?

As to approach it, can no earthly mould.

Page | 174

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

How full of glory then must thy Creator be?

Who gave this bright light luster unto thee:

Admir’d, ador’d for ever, be that Majesty.

VIII

Silent alone, where none or saw, or heard,

In pathless paths I lead my wandring feet,

My humble Eyes to lofty Skyes I rear’d

To sing some Song, my mazed Muse thought meet.

My great Creator I would magnifie,

That nature had, thus decked liberally:

But Ah, and Ah, again, my imbecility!

IX

I heard the merry grasshopper then sing,

The black clad Cricket, bear a second part,

They kept one tune, and played on the same string,

Seeming to glory in their little Art.

Shall Creatures abject, thus their voices raise?

And in their kind resound their makers praise:

Whilst I as mute, can warble forth no higher layes.

X

When present times look back to Ages past,

And men in being fancy those are dead,