1.8: An Introduction to the Arts and Humanities

- Page ID

- 117947

For centuries, scholars, philosophers, and aestheticians have debated over a definition of "art." The challenging range of arguments encompasses, among other considerations, opposing points of view that insist on one hand that "art" must meet a criterion of functionality-that is, be of some societal use-and, on the other hand, that "art" exists for its own sake. In this text, we survey rather than dispute. Thus, in these pages, we will not solve the dilemma of art's definition. For example, we might define "art" as one person's interpretation of reality manifested in a particular medium and shared with others. Such a definition, while agreeable to some, finds objection from others for various reasons, among which is the fact that it is completely open ended and does not speak to quality. It allows anything to qualify as "art" from the simplest expression of art brut, naive art, or "outsider art" such as drawings by children or psychotics to the most profound masterpiece. Such are the tantalizing possibilities for disagreement when we try to define art. We can however examine some characteristics of the arts that enhance our understanding.

Art has always had, a profound effect on the quality of human life, as the pages of this reading will help us to understand. Its study requires seriousness of purpose. But, we must not confuse seriousness of purpose in the study of art with putting works of art on a pedestal. Some art is serious, some art is profound, and some art is highly sacred. However, some art is light, some humorous, and some downright silly, superficial, and self-serving for the artists. But eventually, we will desire to make judgments and once again the text will help sort out the details.

THE ARTS AND WAYS OF KNOWING

We humans are creative species. Whether in science, politics, business, technology, or the arts, we depend upon our creativity almost as much as anything else to meet the demands of daily life. Any study of the arts comprises a story about us; our perceptions of the world as we have come to see and respond to it and the ways we have communicated our understandings to each other since the Ice Age, more than 15,000 years ago.

Photography of Lascaux animal painting from Wikimedia Commons by Prof saxx. Public domain

We have learned a great deal about our world and how it functions since the human species began and we have changed our patterns of existence. However, the fundamental characteristic that makes us human -that is, our ability to intuit and to symbolize- have not changed. Art, the major remaining evidence we have of our earliest times, reflects these unchanged human characteristics in inescapable terms and helps us to understand the beliefs of culture including our own and to express the universal qualities of being human.

Visual art, architecture, music, theatre, dance, literature, and cinema, among other artforms, belong in a broad category of pursuit called the "Humanities." The terms arts and humanities fit together as a piece to a whole. The “Humanities” as a discipline constitutes a larger whole into which the arts fit as one piece. So, when we use the term Humanities, we automatically include the arts. When we use the term arts, we restrict our focus. The arts disciplines- the visual arts, the performing arts, and architecture (including landscape architecture)- typically arrange sound, color, form, movement, and/or other elements in a manner that affects our sense of beauty in a graphic or plastic (capable of being shaped) medium. The humanities include the arts but also include disciplines such as philosophy, literature, and sometimes, history, which comprise branches of knowledge that share a concern with humans and their cultures. We begin our discussion with a look at the humanities.

The Humanities-as opposed to the sciences, for example- can very broadly be defined as those aspects of culture that look into what it means to be human. The sciences seek essentially to describe reality whereas the humanities seek to express humankind's sub jective experiences of reality, to interpret reality, to transform our interior experience into tangible forms, and to comment upon reality, to judge and evaluate. But despite our desire to categorize, few clear boundaries exist between the humanities and the sciences. The basic difference lies in the approach that separates investigation of the natural universe, technology, and social science from the search for truth about the universe undertaken by artists.

Within the educational system, the humanities traditionally have included the fine arts (painting, sculpture, architecture, music, theatre, dance, and cinema), literature, philosophy, and, sometimes, history. These subjects orient toward exploring humanness, what human beings think and feel, what motivates their actions and shapes their thoughts. Many answers lie in the millions of artworks all around the globe, from the earliest sculpted fertility figures to the video and cyber art of today. These artifacts and images comprise expressions of the humanities, not merely illustrations of past or present ways of life.

In addition, change in the arts differs from change in the sciences, for example, in one significant way: New scientific discovery and technology usually displace the old, but new art does not invalidate earlier human expression. Obviously, not all artistic approaches survive, but the art of Picasso cannot make the art of Rembrandt a curiosity of history the way that the theories of Einstein did the views of William Paley. Nonetheless, much about art has changed over the centuries. Using a spectrum developed by Susan Lacy in Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (1994), we learn that at one time an artist may be an experiencer, at another, a reporter, at another, an analyst; and at still another time, an activist. Further, the nature of how art historians see art has changed over the centuries summit- for example, today, we do not use an artist’s biography to justify all of the motivation for his or her work- and we now include works of art from previously marginalized groups such as women and minorities. These shifts in the disciplines of the arts suggest important considerations as we begin to understand the nature of art.

Most importantly, we can approach works of art with the same subtleties we normally apply to human relationships. We know that we cannot simply categorize people as "good " or "bad," as "friends," "acquaintances," or "enemies." We relate to other people in complex ways. Some friendships remain pleasant but superficial, some people are easy to work with, and others become lifelong companions. Also, making a good friend takes time and repeated meetings and shared activities. This is also true of making friends with a painting, or a sculpture or, a ballet. So, when we have gone beyond textbook categories and learned how to approach art with this sort of openness and sensitivity, we find that art, like friendship, has a major place in the growth and quality of life.

THE CONCERNS OF ART

Among other concerns, art has typically concerned creativity, aesthetic communication, symbols, and the fine and applied arts. Let's look briefly at each of these.

CREATIVITY

Art has always evidenced a concern for creativity-that is, the act of bringing forth new forces and forms. We do not know for sure how creativity functions. Nonetheless, something happens in which humankind takes chaos, formlessness, vagueness, and the unknown and crystallizes them into form, design, inventions, and ideas. Creativity underlies our existence. It allows scientists to intuit a possible path to a cure for cancer, for example, or to invent a computer. The same process allows artists to find new ways to express ideas through processes in which creative action, thought, material, and technique combine in a medium to create something new, and that "new thing," often without words, triggers human experience-that is, our response to the artwork.

AESTHETIC COMMUNICATION

Art usually involves communication. Arguably, artists need other people with whom they can share their perceptions. When artworks and humans interact, many possibilities exist. Interaction may be casual and fleeting, as in the first meeting of two people, when neither wishes a relationship. Similarly, an artist may not have much to say, or may not say it very well. For example, a poorly written or produced play will probably not excite an audience. Similarly, if an audience member's preoccupations render it impossible to perceive what the play offers, then at least that part of the artistic experience fizzles. On the other hand, all conditions may be optimum, and a profoundly exciting and meaningful experience may occur: The play may treat a significant subject in a unique manner, the production artists' skills in manipulating the medium may be excellent, and the audience may be receptive. Or the interaction may fall somewhere between these two extremes.

Throughout history, artistic communication has involved aesthetics (ehs-THEHtihks). Aesthetics is the study of the nature of beauty and of art and comprises one of the five classical fields of philosophical inquiry-along with epistemology (the nature and origin of knowledge), ethics (the general nature of morals and of the specific moral choices to be made by the individual in relationship with others), logic (the principles of reasoning), and metaphysics (the nature of first principles and problems of ultimate reality). The term aesthetics (from the Greek for "sense perception") was coined by the German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten (1714-1762) in the mid-eighteenth century, but interest in what constitutes the beautiful and in the relationship between art and nature goes back at least to the ancient Greeks. Plato saw art as imitation and beauty as the expression of a universal quality. For the Greeks, the concept of "art" embraced all handcrafts, and the rules of symmetry, proportion, and unity applied equally to weaving, pottery, poetry, and sculpture. In the late eighteenth century, the philosopher Immanuel Kant (kahnt; 1724-1804) revolutionized aesthetics in his Critique of Judgment (1790) by viewing aesthetic appreciation not simply as the perception of intrinsic beauty, but as involving a judgment-subjective, but informed. Since Kant, the primary focus of aesthetics has shifted from the consideration of beauty per se to the nature of the artist, the role of art, and the relationship between the viewer and the work of art.

SYMBOLS

Art also concerns symbols. Symbols usually involve tangible emblems of something abstract: a mundane object evoking a higher realm. Symbols differ from signs, which suggest a fact or condition. Signs are what they indicate. Symbols carry deeper, wider, and richer meanings. Look at the Greek cross below. A Greek Cross has arms of equal length and was one of the most common Christian forms used in the 4th century. Some people might identify this figure as a plus sign in arithmetic. But as a Greek cross, it becomes a symbol because it suggests many images, meanings, and implications. Artworks use a variety of symbols, and symbols make artworks into doorways leading to enriched meaning.

Greek Cross Public Domain

Symbols occur in literature, art, and ritual. Symbols can involve conventional relationships such as a rose standing for courtly love in a medieval romance. A symbol can suggest physical or other similarities between the symbol and its reference (the red rose as a symbol for blood) or personal associations-for example, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats's use of the rose to symbolize death, ideal perfection, Ireland, and so on. Symbols also occur in linguistics as arbitrary symbols and in psychoanalysis where symbols, particularly images in dreams, suggest repressed, subconscious desires and fears. In Judaism, the contents of the feast table and the ceremony performed at the Jewish Passover seder (a feast celebrating the exodus from slavery in Egypt) symbolize events surrounding the Israelites' deliverance from Egypt. In Cluistian art, the lamb, for example, symbolizes the sacrifice of Christ.

FINE AND APPLIED ART

One last consideration in understanding art's concerns involves the difference between fine art and applied art. The "fine arts"- generally meaning painting, sculpture, architecture, music, theatre, dance, and in the twentieth century, cinema- are prized for their purely aesthetic qualities. During the Renaissance (roughly the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries), these arts rose to superior status because Renaissance values lauded individual expression and unique aesthetic interpretations of ideas. The term “applied art” sometimes includes architecture and the "decorative arts" and refers to art forms that have a primarily decorative rather than expressive or emotional purpose. The decorative arts include handcrafts by skilled artisans, such as ornamental work in metal, stone, wood, and glass, as well as textiles, pottery, and bookbinding. The term may also encompass aspects of interior design. In addition, personal objects such as jewelry, weaponry, tools, and costumes represent the decorative arts. The term may expand, as well, to mechanical appliances and oilier products of industrial design. Nonetheless, even the most common of objects can have artistic flair and provide pleasure and interest. The lowly juice extractor (see below), an example of industrial design, brings a sense of pleasantry to a rather mundane chore. Its two-part body sits on colored rubber feet and reminds us, perhaps, of a robot. Its cream and brown colors are soft and warm, comfortable rather than cold and utilitarian. Its plumpness holds a friendly humor, and we could imagine talking to this little device as an amicable companion rather than regarding it as a mere machine. The term decorative art first appeared in 1791. Many decorative arts, such as weaving, basketry, or pottery, are also commonly considered "crafts," but the definitions of the terms remain somewhat arbitrary and without sharp distinction.

Braun Juice Extractor-"Multipress" available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Quilt art exhibit installation view, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebraska – Lincoln CC BY-SA 3.0

THE PURPOSES AND FUNCTIONS OF ART

Purposes

Another way we can expand our understanding of art involves examining some of its purposes and functions. In terms of the former-- that is, art's purposes-- we ask, What does art do? In terms of the latter-- that is, art's functions-- we ask, How does it do it? Among some of art’s purposes, art can: (1) provide a record; (2) give visible or other form to feelings; (3) reveal metaphysical or spiritual truths; and ( 4) help people see the world in new or innovative ways. Art can do any or all of these. They are not mutually exclusive.

Until the invention of the camera, one of art's principal purposes involved enacting a record of the world. Although we cannot know for sure, very likely cave art of the earliest times did this. And so it went through history. Artists undertook to record their times on vases, walls, canvases, and so on-as in the case of the eighteenth-century Italian painter Canaletto (can-ah-LAY-toh), in highly naturalistic verdute (vair-DOO-tay; Italian for "views") that he sold to travelers doing the grand tour of Europe.

Canaletto - Rialto Bridge from the North Public Domain

Art can also give visible form to feelings. Perhaps the most explicit example of this aspect of art comes in the Expressionist style of the early twentieth century. Here the artist's feelings and emotions toward content formed a primary role in the work.

Edvard Munch, 1893, The Scream, oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard, 91 x 73 cm, National Gallery of Norway Public Domain

In terms of art that reveals metaphysical or spiritual truths, we can turn to the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe, whose light and space perfectly embodied medieval spirituality. The rising line of the cathedral reaches, ultimately, to the point of the spire, which symbolizes the release of earthly space into the unknown space of heaven.

Cologne Cathedral towers CC BY-SA 3.0 de

On the other hand, a tribal ancestor figure deals almost exclusively in spiritual and metaphysical revelation.

Totem pole in Vancouver, British Columbia CC BY-SA 4.0

Finally, most art, if well done, can assist us in seeing the world around us in new and surprising ways. Art that has no representational content may reveal a new way of understanding the interaction of life forces.

Functions

In addition to its purposes-what it does-- art also has many functions; in other words, how it does what it does. This includes (1) enjoyment, (2) political and social commentary, (3) therapy, and (4) artifact. Again, one function is no more important than the others. Nor are they mutually exclusive; one artwork may fill many functions. Nor are the four functions just mentioned the only ones. Rather, they serve as indicators of how art has functioned in the past and can function in the present. Like the types and styles of art that have occurred through history, these four functions and others provide options for artists and depend on what artists wish to do with their artworks.

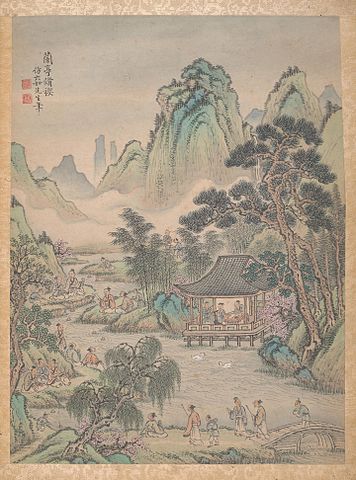

Works of art can provide an escape from everyday cares, treat us to a pleasant experience, and engage us in social occasions. The same artworks we enjoy may also create insights into human experience. We can also glimpse the conditions of other cultures, and we can find healing therapy in enjoyment. An artwork in which one individual finds only enjoyment may function as a profound social and personal comment to another. In the case of a Chinese landscape like Walking by a Mountain Stream, it may raise a plain feature of nature to a profound level of beauty.

Landscape Lu Han; 1699; ink and color on paper donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Albert Bierstadt - Among the Sierra Nevada, California Public Domain

Art may have a political or social function, such as influencing the behavior of large groups of people. It has functioned this way in the past and continues to do so. Eugene Delacroix's (deh-lah-KWAH) painting, Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), illustrates this concept. In July 1830, for three days known as the Trois Glorieuses (the Glorious Three), the people of Paris took up arms to bring in the parliamentary monarchy of Louis-Philippe in hopes of restoring the French Republic. Eager to celebrate July 28, Delacroix painted the allegorical figure of Liberty waving the tricolor flag of France and storming the corpse-ridden barricades with a young combatant at her side. The painting was reviled by conservatives but purchased by Louis-Philippe in 1831. Soon after, it was hidden for fear of inciting public unrest.

Liberty Leading the People Eugene Delacroix Public Domain

The ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes (air-ih-STAH-fuh-neez) used comedy in such plays as The Birds to attack the political ideas of the leaders of ancient Athenian society. In Lysistrata, he attacked war by creating a story in which all the women of Athens go on a sex strike until Athens rids itself of war and warmongers. In nineteenth-century Norway, playwright Henrik Ibsen used An Enemy of the People as a platform for airing the issue of whether a government should ignore pollution in order to maintain economic well-being. In the United States today, many artworks act as vehicles to advance social and political causes, or to sensitize viewers, listeners, or readers to particular cultural situations like racial prejudice and gender equality.

Graffiti from a wall in Bethlehem, Israel. This photograph taken by Pawel Ryszawa

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.

We Have No Property! We Have No Wives! No Children! We Have No City! No Country! — Petition of Many Slaves, 1773 (painted in 1955) Panel 5 of Jacob Lawrence’s series “Struggle… From the History of the American People,”

In a therapeutic function, creating and experiencing works of art may address individuals with a variety of illnesses, both physical and mental. Role-playing, for example, used frequently as a counseling tool in treating dysfunctional family situations, often called psychodrama, has mentally ill patients act out their personal circumstances in order to find and cure the cause of their illness. Here the individual forms the focus. However, art in a much broader context acts as a healing agent for society's general illnesses as well. In hopes of saving us from disaster, artists use artworks to illustrate the failings and excesses of society. In still another vein, the laughter caused by comedy releases endorphins, chemicals produced by the brain, which strengthen the immune system.

Art also functions as an artifact: As a product of a particular time and place, an artwork represents the ideas and technology of that specific time and place. Artworks often provide not only striking examples but occasionally the only tangible records of some peoples. Artifacts, like paintings, sculptures, poems, plays, and buildings, enhance our insights into many cultures, including our own. Consider, for example, the many revelations we find in a sophisticated work like the cast vessel below from Igbo-Ukwu (IGHboh OOK-woo). This artifact from the village of Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria utilizes the cire perdue (sihr pair-DOO) or "lost wax" process and reveals great virtuosity. It tells us much about the vision and technical accomplishment of this ninth- and tenth-century African society.

Bronze ceremonial vessel in form of a snail shell, 9th century, Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria CC BY-SA 3.0

The Igbo-Ukwu vessel, as exemplary of art in a context of cultural artifact, raises the issue of religious ritual. Music, for example, when part of a religious ceremony, has a ritual function but the same musical piece performed in concert comprises a work of art. And theatre- if seen as an occasion planned and intended for presentation- would include religious rituals as well as events that take place in theatres. Often, as a survey of art history would confirm, we cannot discern when ritual stops, and secular production starts. For example, ancient Greek tragedy seems clearly to have evolved from and maintained ritualistic practices. When ritual, planned and intended for presentation, uses traditionally artistic media like music, dance, and theatre, we can legitimately study ritual as art, and see it also as an artifact of its particular culture.

Having said all that about purposes and functions, we must also state that sometimes art just exists for its own sake. In the late nineteenth century, a philosophical artistic movement occurred called aestheticism, characterized by the slogan "art for art's sake." Those who championed this cause reacted against Victorian notions that a work of art must have uplifting, educational, or otherwise socially or morally beneficial characteristics. Proponents of aestheticism held that artworks stand independent and self-justifying, with no reason for being other than being beautiful. The playwright Oscar Wilde said in defense of this viewpoint: "All art is quite useless." His statement meant that exquisite style and polished device had greater importance than utility and meaning. Thus, form is victorious over function. The aesthetes, as proponents of aestheticism were called, disdained the "natural," organic, and homely in art and life and viewed art as the pursuit of perfect beauty and life a quest for sublime experience.

The question of how we go about approaching the arts, or how we study them, presents another challenge. We must choose one of the several methods available and carry on from there. We assume those most of you who are taking this course have had only limited exposure to the arts. So, we have chosen a method of study that can act as a springboard into the arts--it seems logical to begin our study by dealing with some concrete characteristics. In other words, from mostly an intellectual point of view, what can we see and what can we describe when we look at the arts?

To put that question in different terms, how can we sharpen our aesthetic perception?