7.1: Introduction, Historical Context, and Impressionism

- Page ID

- 76229

Music, like the other arts, does not occur in a vacuum. Changes brought on by advances in science, and inventions resulting from these advances, affected composers, artists, dancers, poets, writers, and many others at the turn of the twentieth century. Inventions from the late Romantic era had a great impact on economic and social life in the twentieth century. These inventions included the light bulb, the telephone, the automobile, and the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877 and patented it in 1878. While researching means to improve the telegraph and telephone, Edison developed a way to record sound on tinfoil-coated cylinders. He would speak into a mouthpiece and the recording needle would indent a groove into the cylinder. The playing needle would then follow the groove, and the audio could be heard through a horn speaker (in the shape of a large cone). Edison improved his invention and formed the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to market the invention. Edison’s phonograph had an especially great influence on the spread of music to larger audiences; he also advertised the device’s usefulness for dictation and letter writing, recording books for the blind, recording and archiving family members’ voices, music boxes, toys, and clocks that verbally announce the time with prerecorded voices. In 1917, such audio phonograph devices were purchased by the U.S. Army for $60 each and used to make troops feel closer to home during World War I. Listen to this rare audio clip of Edison expressing his thanks to the troops for their service and sacrifice: www. americaslibrary.gov/assets/aa/edison/aa_edison_phonograph_3.wav

What defines twentieth-century music? Clearly, the twentieth century was a time of great upheaval in general, including in music. The sense of rapid change and innovation in music and art of this period is a reflection of the dramatic changes taking place in the world at large. On a political level, the twentieth century was one of the bloodiest and most turbulent periods in history. While wars are a constant throughout all of human history, the global nature of twentieth-century politics resulted in conflicts on a scale never before seen; World War II alone is widely regarded as the deadliest conflict in human history in terms of total deaths, partly due to advancements in technology such as machine guns, tanks, and eventually the atom bomb.

It’s no surprise that music of this period mirrored the urgency and turmoil in the world at large. For many composers, the raw emotion and sentimentality reflected in the music of the nineteenth century had grown tiresome, and so they began an attempt to push the musical language into new areas. Sometimes, this meant bending long-established musical rules to their very limits, and, in some cases, breaking them altogether. One of the by-products of this urgency was fragmentation. As composers rushed to find new ways of expressing themselves, different musical camps emerged, each with their own unique musical philosophies. We now categorize these musical approaches with fancy terms ending in “-ism,” such as “primitivism,” “minimalism,” “impressionism,” etc. We will discuss many of these individual movements and techniques as well as address what makes them unique, but before we do this, let’s first talk about those things that most (but not all) music of the twentieth century has in common.

7.3.1 Melody

One of the ways in which composers deviated from the music of the nineteenth century was the way in which they constructed melodies. Gone were the singable, sweeping tunes of the Romantic era. In their place rose melodies with angular shapes, wide leaps, and unusual phrase structures. In some cases, melody lost its status as the most prominent feature of music altogether, with pieces that featured texture or rhythm above all else.

7.3.2 Harmony

The most obvious difference between twentieth-century music and what pre- ceded it is the level of harmonic dissonance. This is not a new phenomenon. The entire history of Western music can be viewed in terms of a slowly increasing acceptance of dissonance, from the hollow intervals of the Middle Ages all the way to the lush chords of the nineteenth century. However, in the twentieth century the use of dissonance took off like a rocket ship. Some composers continued to push the tolerance level for dissonance in the context of standard tonal harmony. One example is through the use of polytonality, a technique in which two tonal centers are played at the same time. Some composers sought to wash their hands of the rules of the past and invented new systems of musical organization. Often, this resulted in music that lacked a tonal center, music that we now refer to as atonal. Some com- posers such as Igor Stravinsky even tried their hand at more than one style.

7.3.3 Rhythm

In preceding centuries, music was typically relegated to logical, symmetrical phrases that fell squarely into strict meters. That all changed at the dawn of the twentieth century. Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring famously undermined the au- dience’s expectation of the role of rhythm by abandoning strict meter for rapidly changing time signatures. Instead of the steady familiar time signatures containing three or four beats, Stravinsky peppered in measures containing an odd number of beats such as five or seven. This created a sense of unease in the audience by removing something from the music that they had previously taken for granted: a steady and unwavering sense of meter. In America, the rhythmic innovations of ragtime and jazz influenced both Western art music and popular music from that time on. Especially important was the use of syncopation, which was addressed in the first chapter.

7.3.4 Texture and Timbre

As memorable melodies and traditional harmonies began to break down, some composers looked to new tonal colors through the use of new instruments such as synthesizers, instruments that electronically generate a wide variety of sounds. In other cases, traditional instruments were used in nontraditional ways. For example, John Cage famously composed piano pieces that called for objects such as coins and tacks to be placed on the strings to create unique effects.

7.3.5 The Role of Music

Music has had many roles throughout history. The music of Josquin helped enhance worship. The works of Haydn and Mozart reflected the leisurely life of the aristocracy. Opera served as a form of musical escapism in the daring and ambitious works of composers such as Wagner. In the twentieth century, music began to move away from entertainment into the realm of high art. Composers sought to challenge the listener to experience music in new ways and in some cases to reevaluate their fundamental notions of what music is. This sense of revolution was not limited to music; it was also taking place throughout the art world. As we discuss the many “-isms” in music, we will see direct parallels with the visual arts.

7.3.6 Compositional Styles: The “-isms”

Near the beginning of the twentieth century, numerous composers began to rebel against the excessive emotionalism of the later Romantic composers. Two different styles emerged: the Impressionist style led by Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, and the atonal Expressionist style led by Arnold Schoenburg. Both styles attempted to move away from the tonal harmonies, scales, and melodies of the previous period. The impressionists chose to use new chords, scales, and colors while the expressionists developed a math-based twelve-tone system that attempted to completely destroy tonality.

7.3.7 Impressionism

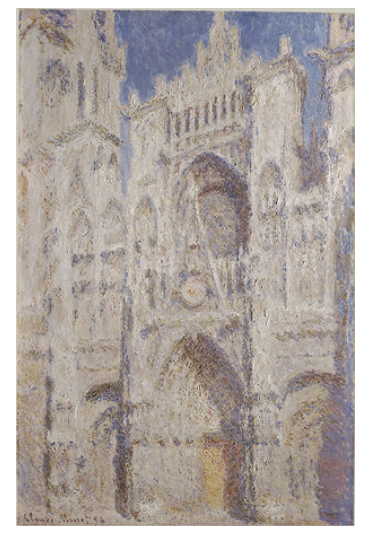

The two major composers associated with the Impressionist movement are Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Both French-born composers were searching for ways to break free from the rules of tonality that had evolved over the previous centuries. Impressionism in music, as in art, focused on the creator’s impression of an object, concept, or event. The painting labeled Image 7.1, by the French impressionist painter Claude Monet, suggests a church or cathedral, but it is not a clear portrait. It comprises a series of paint daubs that suggest something that we may have seen but that is slightly out of focus.

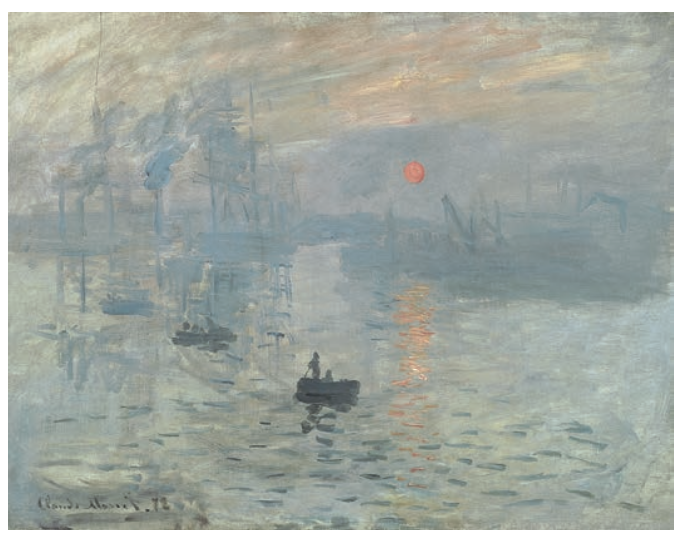

In the painting labeled Image 7.2, we see how Monet distilled a scene into its most basic elements. The attention to detail of previous centuries is abandoned in favor of broad brushstrokes that are meant to capture the momentary “impression” of the scene. To Monet, the objects in the scene, such as the trees and boats, are less important than the interplay between light and water. To further emphasize this interplay, Monet pares the color palate of the painting down to draw the focus to the sunlight and the water.

Similarly, Impressionist music does not attempt to follow a “program” like some Romantic compositions. It seeks, rather, to suggest an emotion or series of emotions or perceptions.

Listen to the example of Debussy’s La Mer (The Sea) linked below. Pay particular attention to the way the music seems to rise and fall like the waves in the sea and appears to progress without ever repeating a section. Music that is written this way is said to be “through-composed.” The majority of impressionist music is written in this manner. Even though such music refrains from following a specific program or story line, La Mer as music suggests a progression of events through- out the course of a day at sea. Note that Debussy retained the large orchestra first developed by Beethoven and used extensively by Romantic composers. This music, unlike the Expressionism we will visit next, is tonal and still uses more traditional scales and chords.

debussy, La Mer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlR9rDJMEiQ

Impressionist composers also liked using sounds and rhythms that were unfamiliar to most Western European musicians. One of the most famous compositions by Maurice Ravel is entitled Bolero. A Bolero is a Spanish dance in three-quarter time, and it provided Ravel with a vehicle through which he could introduce different (and exotic, or different sounding) scales and rhythms into the European orchestral mainstream. This composition is also unique in that it was one of the first to use a relatively new family of instruments at the time: the saxophone family. Notice how the underlying rhythmic pattern repeats throughout the entire composition, and how the piece gradually builds in dynamic intensity to the end.

maurice ravel, Bolero https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A2BYkJS8GE0

Unlike composers such as Bach, Ravel was not born into a family of musicians. His father was an engineer, but one who encouraged Ravel’s musical talents. After attending the Paris Conservatory as a young man, Ravel drove a munitions truck during World War I. Throughout all this time, he composed compositions of such lushness and creativity that he became one of the most admired composers in France, along with Claude Debussy. His best known works are the aforementioned Bolero, Concerto in D for Piano, La valse, and an orchestral work entitled Daphnes et Chloe.

Daphnis et Chloé was originally conceived as a ballet in one act and three scenes and was loosely based on a Greek drama by the poet Longus. The plot on which the piece is based concerns a love affair between the title characters Daphnis and Chloe. The first two scenes of the ballet depict the abduction and escape of Chloe from a group of pirates. However, it is the third scene that has become so immortalized in the minds of music lovers ever since. “Lever du jour,” or “Day- break,” takes place in a sacred grove and depicts the slow build of daybreak from the quiet sounds of a brook to the birdcalls in the distance. As dawn turns to day, a beautiful melody builds to a soaring climax, depicting the awakening of Daphnis and his reunion with Chloe.

After the ballet’s premier in June of 1912, the music was reorganized into two suites, the second of which features the music of “Daybreak.” Listen to the record- ing below and try to imagine the pastel colors of daybreak slowly giving way to the bright light of day.

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: |

| Composer: Maurice Ravel |

| Composition: Daphnis and Chloe, Suite No. 2: “Lever du jour” |

| Date: 1913 |

| Genre: Orchestral Suite |

| Form: Through-composed |

| Performing Forces: orchestra/chorus |

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|

0:00 |

Murmuring figures depicting a brook. |

| 0:52 | Sweeping melody reaches first climax, and then dies down slowly. Strings over murmuring accompaniment. |

| 1:09 | Strings and clarinet enter with song-like melody. Melody over murmuring strings. |

| 1:30 |

Flute enters with dance-like melody. Melody over murmuring strings |

| 1:48 | Clarinet states a contrasting melody. Melody over murmuring strings. |

| 2:13 |

Chorus enters while strings continue melody. Melody over murmuring strings and “Ah” of chorus. |

| 2:53 |

Melody rises to a climax and then slowly diminishes. Full Orchestra and Chorus. |

| 3:13 |

Sweeping melody enters in strings to a new climactic moment. Full Orchestra. |

| 3:19 |

Motif starts in low strings and then rises through the orchestra. Full Orchestra. |

| 4:05 |

Chorus enters for a final climactic moment, then slowly dies away. Full Orchestra and Chorus. |

| 4:34 |

Oboe enters with repeating melody. |

| 4:58 |

Clarinet takes over repeating melody and the piece slows to a stop. |