3.2: Selecting a Topic

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 23332

Learning Objectives

- Identify strategies for personalizing an assigned topic

- Identify strategies for finding a focus for an unassigned topic

- Identify strategies for moving from general to specific

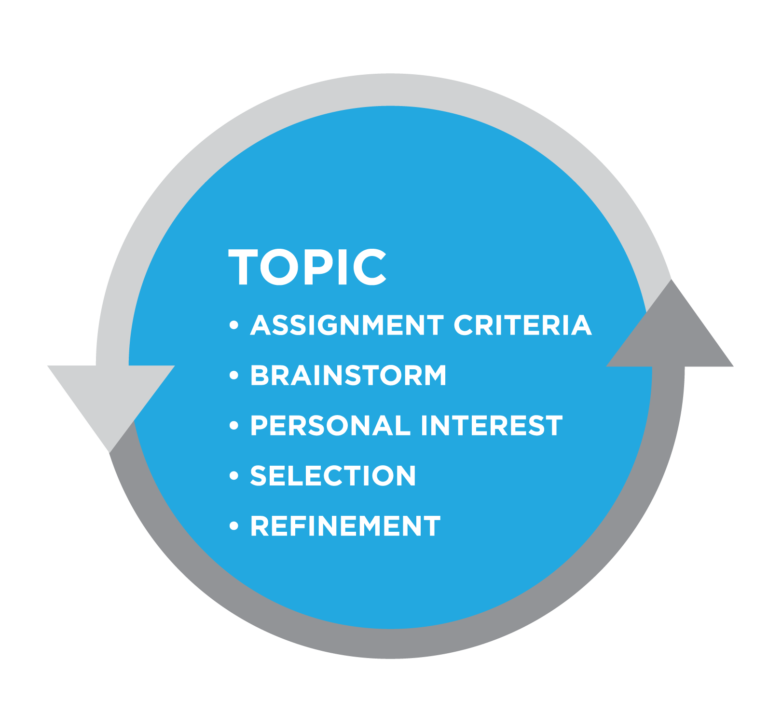

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Some instructors who assign writing projects will leave the choice of what to write about up to you. Others will have a very defined set of topics for you to write from. But even when an instructor assigns a given topic or offers a choice of assigned topics, you have a lot of opportunity for creativity.

The real issue here is approach. When you come to an assigned essay as a project, how you first engage with it will determine your overall experience. Some students see any writing assignment as an externally imposed task — something they have to do in order to pass the course. This approach will guarantee that those students will eventually hate their assignments, possibly their instructor, and when push comes to shove the whole project of being in school.

Solution: Choosing an Approach to Your Topic

Deliberately choosing how you approach your topic will help you not only choose one that will satisfy the requirements, but also ensure that you enjoy the process of research and writing. After all, no one on earth can do what you do. So, only you can figure out how to write a great essay in your own voice.

It all starts with selecting a topic. How you approach that selection process is vastly important.

The key is to identify what made you take the class in the first place. Something about this class captured your fancy and made you register (particularly in the case of an elective), so place that interest at the heart of your topic.

Look to what you were interested in as a way of finding your paper topic! Use that initial fascination to twist the topic of your paper so that it becomes an excuse to wallow in whatever got you interested in that class in the first place.

Avoiding the Pit of Despair

Whatever you do, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that your work is simply a required box that needs to be checked and you can’t bring any creativity to the table. Even if the class was required for your program or degree, you still chose that program. There are ways to make almost any writing task enjoyable, or at least something you gain something interesting out of.

How to Come Up With a Topic to Write About

Many people are intimidated by the thought of writing. One of the biggest factors that can contribute to writers’ block is not knowing what to write about. If you can find a topic that interests you, your writing will likely flow more readily and you will be more likely to write a successful piece. Use a variety of strategies for coming up with something to write about to find what works best for your writing and learning style.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Understand the Essay Assignment

Understanding the assigned essay is the first step to coming up with a topic. Knowing the type of essay that is expected, the length of the essay, and to what degree research is expected will all determine the scope of the topic you will choose.

Evaluate the Purpose of the Assignment

The purpose of the assignment will also determine the type of topic. A persuasive essay, for example, will have a much different type of topic than a personal experience essay.

- Look for key action words like compare, analyze, describe, synthesize, and contrast. These words will help you determine what your teacher wants you to do in the essay.

Select a Topic from a Provided List

If your instructor has provided a list of topics for you, choose a topic from the given list. It is likely that the topics have been gathered together because they are an appropriate scope and breadth and the instructor has found that the topics have led to successful essays in the past.

- Choose the topic for which a main idea comes most naturally and for which you feel you can develop the paper easily.

Brainstorm a List of Ideas

Write down a list of ideas that come to mind. They don’t have to be good ideas, but it’s good to just start writing a list to get your ideas flowing. Just write down everything you can think of; you can evaluate the ideas later.

This video demonstrates that writers of all levels and experiences value the process of brainstorming. Watch brainstorming in action for a television sitcom.

Freewrite for a Predetermined Amount of Time

Decide ahead of time how long you want to freewrite, then just write without stopping.

- Most people write for 10-20 minutes.

- Do not stop writing, even if you need to just write “blah blah blah” in the middle of a sentence.

- Hopefully, you will write yourself towards a useful thought or idea through freewriting. Even if it does not give you content you can use in your essay, it can be a valuable writing warm-up.

Create a Visual Representation of Your Ideas

Especially if you are a visual learner, creating a visual representation of your ideas may help you stumble onto or narrow down ideas to a good topic.

- Use a mind map. The center of the mind map contains your main argument, or thesis, and other ideas branch off in all directions.

- Draw an idea web. This a visual that uses words in circles connected to other words or ideas. Focusing on the connections between ideas as well as the ideas themselves may help you generate a topic.

Remember What the Teacher Focused On In Class

If you are writing an essay for a class, think about what the teacher spent a lot of time talking about in class. This may make a good choice for an essay, as the teacher clearly thinks it’s something important.

- Review your class notes and see if there is anything that stands out as interesting or important.

- Review any handouts or focus sections of a text that were assigned.

Think About What Interests You

![Writing on whiteboard. In red, central, "Why do people participate in open culture?" Clockwise, around this central question, is written Sharing accelerates progress and innovation. What do you think? Knowledge rights. "It's the right thing to do." Value. Transparency. Sharing. Freedom. Community. Connect with like-minded people. Fun! Join exciting projects. "I just love it!" Can't afford the pay-wall. Necessity. "I need this feature." No relevant materials. Accessible = creativity. #WhyOpen. [just coz']. Build self-confidence. Learn new skills. "I'm free to express my creativity." Empowerment. Develop new ideas. Several brains better than 1. "No need to reinvent the wheel." Cross-pollination. Constant feedback loops. Efficiency. More cost-effective.](https://human.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/1844/9472941659_bc592c5cd6_z-300x200.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Writing something you care about or that you are interested in is much easier than making yourself write about things that seem boring. Make a list of your interests and see if there is a way to connect one or more of them to your essay.

Consider the List You Have Generated

Write a few additional notes next to each potential topic and evaluate whether each item would be an appropriate topic. At this point, you should be able to narrow your list down to a few good choices.

- You may want to ask your teacher if you have narrowed down your ideas to two or three items. She may have some insight as to which topic would be the most successful.

- Go back and look at the original assignment again and determine which of your narrowed topics will best fit with the intent of the essay assignment.

When to Narrow Down a Topic

Most students will have to narrow down their topic at least a little. The first clue is that your paper needs to be narrowed is simply the length your professor wants it to be. You can’t properly discuss “war” in 1,000 words, nor talk about orange rinds for 12 pages.

Steps to Narrowing a Topic

- First start out with a general topic. Take the topic and break it down into categories by asking the five W’s and H.

- Who? (American Space Exploration)

- What? (Manned Space Missions)

- Where? (Moon Exploration)

- When? (Space exploration in the 1960’s)

- Why? (Quest to leave Earth)

- How? (Rocket to the Moon: Space Exploration)

- Now consider the following question areas to generate specific ideas to narrow down your topic.

- Problems faced? (Sustaining Life in Space: Problems with space exploration)

- Problems overcome? (Effects of zero gravity on astronauts)

- Motives? (Beating the Russians: Planning a moon mission)

- Effects on a group? (Renewing faith in science: aftershock of the Moon mission)

- Member group? (Designing a moon lander: NASA engineers behind Apollo 11)

- Group affected? (From Test Pilots to Astronauts: the new heroes of the Air force)

- Group benefited? (Corporations that made money from the American Space Program)

- Group responsible for/paid for _____ (The billion dollar bill: taxpayer reaction to the cost of sending men to the moon)

- Finally, refine your ideas by by considering the S.O.C.R.A.P.R. model.

- S = Similarities (Similar issues to overcome between the 1969 moon mission and the planned 2009 Mars Mission)

- O = Opposites (American pro and con opinions about the first mission to the moon)

- C = Contrasts (Protest or patriotism: different opinions about cost vs. benefit of the moon mission)

- R = Relationships (the NASA family: from the scientists on earth to the astronauts in the sky)

- A = Anthropomorphisms [interpreting reality in terms of human values] (Space: the final frontier)

- P = Personifications [giving objects or descriptions human qualities] (the eagle has landed: animal symbols and metaphors in the space program)

- R = Repetition (More missions to the moon: Pro and Con American attitudes to landing more astronauts on the moon)