3.2: There is no one-size-fits-all essay structure, but there are useful patterns

- Page ID

- 15673

(1000 words)

Understand the limits of the #5paragraphessay

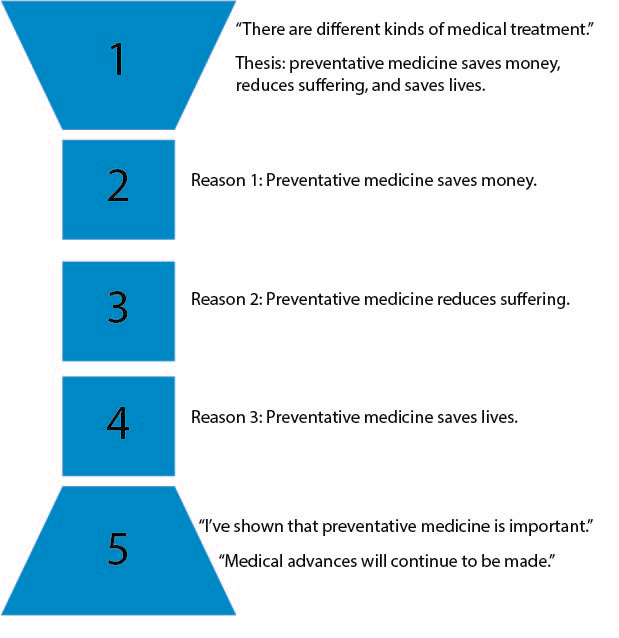

You might be familiar with the five-paragraph essay structure, in which you spend the first paragraph introducing your topic, culminating in a thesis that has three distinct parts. That introduction paragraph is followed by three body paragraphs, each one of those going into some detail about one of the parts of the thesis. Finally, the conclusion paragraph summarizes the main ideas discussed in the essay and states the thesis (or a slightly re-worded version of the thesis) again.

This structure has some benefits

- It helps get your thoughts organized

- It is a good introduction to structuring an essay, letting students focus on content rather than wrestling with a more complex structure.

- It familiarizes students with the general shape and components of many essays

- It is an effective structure for in-class essays or timed written exams.

By adding a "But" to statements, we can begin to see alternatives

- It helps get your thoughts organized, BUT it also constrains your thinking, forcing you to start on a new idea with each paragraph rather than giving you the time to develop your ideas

- It is a good introduction to structuring an essay, letting students focus on content rather than wrestling with a more complex structure, BUT wrestling with the structure of an essay forces you to understand the relationship between your ideas

- It familiarizes students with the general shape and components of many essays, BUT it lulls students into a false sense of comfort that all essays can follow this pattern

- It is an effective structure for in-class essays or timed written exams, BUT you will NEVER do these kinds of writing again after you graduate

The substantial time you spent mastering the 5paragraphessay form was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your professors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

What follows are some strategies for developing an effective essay structure. In the sections that follow, you'll learn more about the specific parts of essays: introductions, thesis statements, body paragraphs, and conclusions.

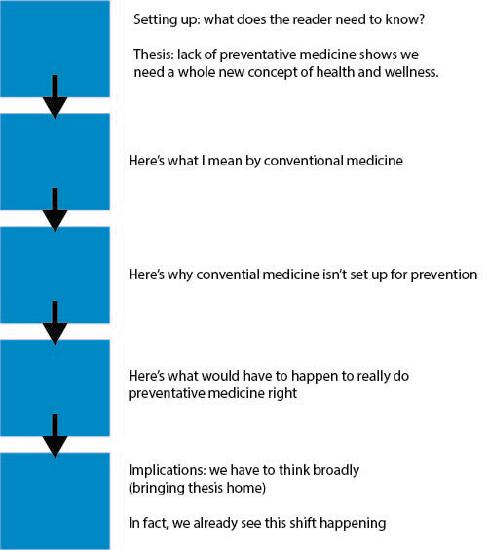

Organically structured essays

Compare these two essay formats. One follows the standard 5paragraphessay form. The other shows a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

Yes, But, So: a different kind of 5paragraphessay

Consider the example above again. Imagine writing about about the problem of 5paragraphessays. You could write that essay in the 5paragraphessay format.

Thesis: The three problems with 5paragraphessays are X, Y, Z.

Body Paragraph 1: X is a problem ...

Body Paragraph 2: Y is a problem ...

(you get the idea)

Where does this essay take you? What big idea does it leave you with? Instead, you can use a pattern like Yes, But, So

Body Paragraph 1: Yes, many people like 5paragraphessays because ...

Body Paragraph 2: But, there are problems with 5paragraphessays ...

Body Paragraph 3: So, instead of writing 5paragraphessays, students should...

But wait! What about my thesis? In this paper, the "So" is your thesis. You might not know what your "So" is when you start. Writing a draft of an essay should be an act of discovering your ideas (Composition scholars refer to this as Writing to Learn). Very very very often, even when you start off with a clear sense of your main point, you'll end up having by the end of the essay a much clearer statement of your point than you did when you started.

Thesis: (Reasons and Importance) 5paragraphessays don't encourage critical thinking or prepare students for real world writing situations, (Stance) so instead students should be encouraged to experiment with different essay forms.

Or, Students should be encouraged to write essays that encourage critical thinking and prepare them for real world writing situations.

The Yes, But, So pattern has another advantage: it follows the pattern of stories.

Stories begin by telling you how things are. "Once upon a time, there was a ..."

But, something happens that causes a change

So, the hero of the story has to solve the problem

Consider the example of a rhetorical analysis assignment: Analyze the rhetorical strategies used in a newspaper opinion essay. Last chapter, you were introduced to the three rhetorical appeals (Logos, Ethos, and Pathos). So, you might want to write a 5paragraphessay

Thesis: the opinion essay uses Logos, Pathos, and Ethos to make a good argument

Body Paragraph 1: The opinion essay uses Logos . . .

(you get the idea)

The Yes, But, So pattern can still work here.

Body Paragraph 1: Yes, the essay is effective at times...

Body Paragraph 2: But, it's not as effective when it ...

Body Paragraph 3: So, my overall judgement of the essay is ...

If you look carefully, you will see the Yes, But, So pattern repeated over and over again. Even the organic essay structure follows Yes, But, So.

Finally, it is useful because it can expanded or contracted to fit nearly any size. It can even be a single sentence

I think we should eat pizza, but you think we should eat tacos, so we should go to the combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell

[adapted from From Competence to Excellence (Guptil) and The Word on College Reading and Writing (Babin, et al)]