2.1: Research Questions and Strategy Documents

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 103160

Scenario

Sarah’s art history professor just assigned the course project and Sarah is delighted that it isn’t the typical research paper. Rather, it involves putting together a website to help readers understand a topic. It will certainly help Sarah get a grasp on the topic herself! Learning by attempting to teach others, she agrees, might be a good idea.

The professor wants the web site to be written for people who are interested in the topic and with backgrounds similar to the students in the course. Sarah likes that a target audience is defined, and since she has a good idea of what her friends might understand and what they would need more help with, she thinks it will be easier to know what to include in her site. Well, at least easier than writing a paper for an expert like her professor.

An interesting feature of this course is that the professor has formed the students into teams. Sarah wasn’t sure she liked this idea at the beginning, but it seems to be working out okay. Sarah’s team has decided that their topic for this website will be 19th century women painters. But her teammate Chris seems concerned, “Isn’t that an awfully big topic?” The team checks with the professor, who agrees they would be taking on far more than they could successfully explain on their website. He suggests they develop a draft thesis statement to help them focus, and after several false starts, they come up with:

The involvement of women painters in the Impressionist movement had an effect upon the subjects portrayed.

They decide this sounds more manageable. Because Sarah doesn’t feel comfortable with the technical aspects of setting up the website, she offers to start locating resources that will help them to develop the site’s content.

Before we learn more about what happens with Sarah and her team, let’s look at the components of the Plan pillar.

Plan Pillar

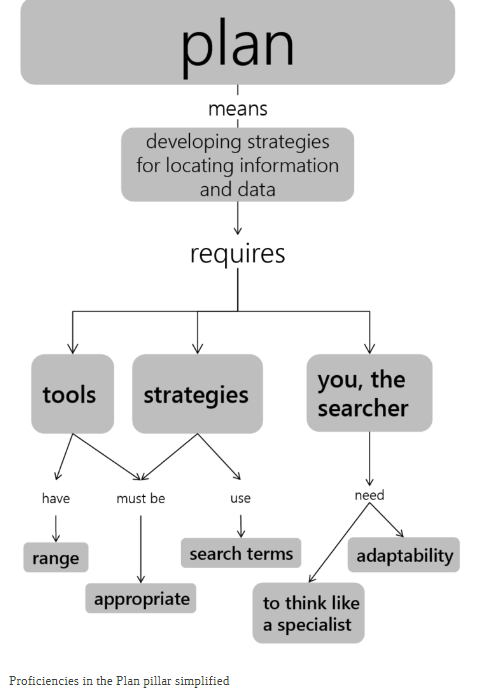

I've provided information in text and graphic form for the Plan Pillar. Mastering the Plan Pillar means you have the ability to: “construct strategies for locating information and data.” That is a fairly short sentence, but it packs a punch. It includes

- Understanding a range of searching techniques

- Understanding the various tools and how they differ

- Knowing how to create effective search strategies

- Being open to searching out the most appropriate tools

- Understanding that revising your search as you proceed is important

- Recognizing that subject terms are of value

And these are just the items to understand! There are also the things you need to be able to do:

- Clearly phrase your search question.

- Develop an appropriate search strategy, using key techniques.

- Selecting good search tools, including specialized ones.

- Use the terms and techniques that are best suited to your search.

Here is a visual representation of these components:

Now take a look at the essence of these items condensed into another concept map:

The second concept map is simplified. The focus is on the key elements: the tools and strategies that you use and the mindset that will help you as you plan your research. This may seem a bit daunting, so let’s see how Sarah tackles the project.

She sometimes falters, but that happens even to experienced researchers. As you read through Sarah’s quest for good information, think about the range and appropriateness of the strategies she uses. What would you do differently? What approaches seem to be good ones?

As you read about Sarah’s quest for information, and reflect on your own information searches in the past, remember particularly the bullet within the Plan pillar that emphasizes the need to revise your search as you work. It is very important to do this, and to build time into the process so you are able to revise.

As you learn more about your topic, or the terms used in conjunction with its concepts, or key scholars in the field, it is only natural that you will need to shift focus, and, perhaps, change course. This is a natural part of the research process and indicates that your efforts are bearing fruit. Let’s return to Sarah…

Sarah Continued

The next time the class meets, Sarah tells her teammates what she has done so far:

“I thought I’d start with some scholarly sources, since they should be helpful, right? I put a search into the online catalog for the library, but nothing came up! The library should have books on this topic, shouldn’t it? I typed the search in exactly as we have it in our thesis statement. That was so frustrating. Since that didn’t work, I tried Google, and put in the search. I got over 8 million results, but when I looked over the ones on the first page, they didn’t seem very useful. One was about the feminist art movement in the 1960s, not during the Impressionist period. The results all seemed to have the words I typed highlighted, but most really weren’t useful. I am sorry I don’t have much to show you. Do you think we should change our topic?”

Alisha suggests that Sarah talk with a reference librarian. She mentions that a librarian came to talk to another of her classes about doing research, and it was really helpful. Alisha thinks that maybe Sarah shouldn’t have entered the entire thesis statement as the search, and maybe she should have tried databases to find articles. The team decides to brainstorm all the search tools and resources they can think of.

Here’s what they came up with:

Search Tools & Resources:

- Wikipedia

- Professor

- Google search

- JSTOR database

Based on your experience, do you see anything you would add?

Sarah and her team think that their list is pretty good. They decide to take it further and list the advantages and limitations of each search tool, at least as far as they can determine.

|

Search Tool |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|

|

Wikipedia |

Easy access; list of references |

Professor doesn't seem to like it; maybe misinformation? |

|

Professor |

The expert! |

Not sure we can get to office hours; we want to appear self-directed |

|

Google search |

Lots of results |

We need a better search term |

|

JSTOR database |

Authoritative, scholarly articles |

None that we know of |

Self Reflection

As you work through your own research quests, it is very important to be self-reflective. The first couple of items in this list where discussed in week 2 in excerpts from the Identify chapter:

- What do you really need to find?

- Do you need to learn more about the general subject before you can identify the focus of your search?

- How thoroughly did you develop your search strategy?

- Did you spend enough time finding the best tools to search?

- What is going really well, so well that you’ll want to remember to do it in the future?

Another term for what you are doing is metacognition, or thinking about your thinking. Reflect on what Sarah is going through as you read this chapter. Does some of it sound familiar based on your own experiences?

You may already know some of the strategies presented here. Do you do them the same way? How does it work? What pieces are new to you? When might you follow this advice? Don’t just let the words flow over you. Instead, think carefully about the explanation of the process. You may disagree with some of what you read. If you do, follow through and test both methods to see which provides better results.

Selecting Search Tools

Let's move away from Sarah and start thinking about this process in terms of this week's assignments and beyond. You have picked a topic that you will focus on for the next several weeks. Now is the time to begin the planning process to gather all the elements that are needed for your mid-term project.

One of the first steps is to start to think about where you can look for information. Part of planning to do research is determining which search tools will be the best ones to use. This applies whether you are doing scholarly research or trying to answer a question in your everyday life, such as what would be the best place to go on vacation.

“Search tools” might be a bit misleading, since a person might be the source of the information you need. Or it might be a web search engine, a specialized database, an association—the possibilities are endless. Often people automatically search Google first, regardless of what they are looking for. Choosing the wrong search tool may just waste your time and provide only mediocre information, whereas other sources might provide really spot-on information and quickly, too. In some cases, a carefully constructed search on Google, particularly using the advanced search option, will provide the necessary information, but other times it won’t. This is true of all sources: make an informed choice about which ones to use for a specific need.

So, how do you identify search tools? Let’s begin with a first-rate method. For academic research, talking with a librarian or your professor is a great start. They will direct you to those specialized tools that will provide access to what you need. If you ask a librarian for help, they may also show you some tips about searching in the resources.

If neither your professor nor a librarian is available when you need help, check your school’s library website to see what guidance is provided. At CRC, we have a database directory that lists, describes, and provides links to all of our databases. We also have program research guides that might offer some clues as to which databases are a good fit for specific disciplines.

Finding Background Information

You have picked a topic, but you'll likely need to refine it to decide exactly what aspects you will focus on in your research. One of the best ways to do that is to get some good background information. This is a time to read all you can about your topic without worrying about exactly what you want to say in your paper. Instead, pay attention to issues that interest you, and take note of concepts, organizations, people, studies, or events that you might want to research further. You've already done a little of this when you listened to your podcast. You should have taken notes that might include the names of researchers, places where studies have been conducted, or other information that might be useful. Notice what details are sticking in your mind; what aspects interest you the most. One of those aspects could become the issue you focus on in your midterm project.

Here are a few library resources that are great for background research:

-

Gale Ebooks: Find the library’s research databases page, and select Gale Ebooks from the General section (at the top). This is a database of subject encyclopedias, and it’s a great place to find solid background information. Search for your topic and look for any related or narrower topics that you’ve identified.

-

CQ Researcher: If your topic is a current social issue, try the CQ Researcher database (also in the General Section on the Research Databases page). CQ Researcher provides overview reports on current issues and can be a treasure trove of information. Look for a timeline of events related to your topic, an overview of the issue, and even different perspectives on possible solutions.

-

Opposing Viewpoints: This database also covers many current and social issues. It's found in the controversial topics section of the databases page. Featured issues are profiled each day. You can also do a keyword search or browse by topics. Results in this page are organized by source type, meaning all the scholarly articles, news articles, and other source types are grouped together.

From Background to Research Question

Because a thesis comes in the beginning of your paper, speech, or research project, you might be tempted to start there. But instead of creating your thesis first, use your background information to ask a

research question. A research question will guide your search by giving you a goal and focus for your paper.

Here are some examples of how to narrow a few broad topics into manageable research questions:

- Broad topic: Homelessness

- Research question: What approach should cities use to help homeless people get housing?

- Broad topic: Kids and sleep

- Research question: How does the early morning start time of high schools affect students’ academic performance?

- Broad topic: Education

- Research question: How can we make sure more kids have access to high-quality preschool?

You’ll notice that these questions cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no”. Instead, you have to explain the answer using details. Good research questions often make you look for causes/effects of an issue, relationships between events and ideas, and/or solutions to a problem.

Keywords

Once you’ve selected some good background sources for your topic, it is time to move on to identifying words you will use to search for more detailed and in-depth information to help answer your research question.

This is sometimes referred to as building a search query. When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Ask yourself, what are the most important words in this question? They are often the nouns.

Don’t enter an entire sentence, or a full question. Different databases and search engines process such queries in different ways, but many look for the entire phrase you enter as a complete unit, rather than the component words.

While some will focus on just the important words, such as Sarah’s Google search that you read about earlier, more often, the results are still unsatisfactory. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic.

You'll also want to think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term doesn’t produce any or enough results. This may sound strange, since if you are looking for

information using a Web search engine, you almost always get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

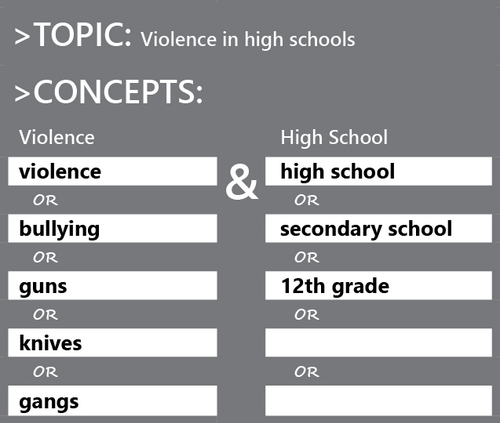

The following image is an example of a process you can use to brainstorm search terms. It illustrates how you might think about the topic of violence in high schools. Notice that this exact phrase is not what will be used for the search. Rather, it is a starting point for identifying the terms that will eventually be used.

Sarah's Topic

Now, let's think of this process using the topic Sarah’s team is working on. They have divided their topic into four concepts and brainstormed multiple search terms for each concept.

Keep in mind that the number of concepts will depend on what you are searching for. And that the search terms may be synonyms or narrower terms. Occasionally, you may be searching for something very specific, and in those cases, you may need to use broader terms as well.

Let's see what Sarah's team came up with:

Machine readable text document of preceding graphic

This chapter was compiled, reworked, and/or written by Andi Adkins Pogue and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Original sources used to create content (also licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0):

Los Rios Libraries. (2020). Getting started with research. Los Rios libraries information literacy tutorials. https://lor.instructure.com/resources/44fe428e10b347bea9892a63482f55fd?shared

Plan: Developing research strategies. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/plan-developing-research-strategies/