1.2.1: Organizing Your Time

- Page ID

- 25707

Original Content by Dave Dillon

When you know what you want to do, why not just sit down and get it done? The millions of people who complain frequently about “not having enough time” would love it if it were that simple! Time management isn’t actually difficult, but you do need to learn how to do it well.

Technically, time cannot be managed, but we label it time management when we talk about how people use their time. We often bring up efficiency and effectiveness when discussing how people spend their time, but we cannot literally manage time because time cannot be managed. What we can do though, is find better ways to spend our time, allowing us to accomplish our most important tasks and spend time with the people most important to us. Time management for successful college studying involves these factors:

- Determining how much time you need to spend studying.

- Knowing how much time you actually have for studying and increasing that time if needed.

- Being aware of the times of day you are at your best and most focused.

- Using effective long- and short-term study strategies.

- Scheduling study activities in realistic segments.

- Using a system to plan ahead and set priorities.

- Staying motivated to follow your plan and avoid procrastination.

For every hour in the classroom, college students should spend, on average, about two hours on that class, counting reading, studying, writing papers, and so on. If you’re a full-time student with fifteen hours a week in class, then you need another thirty hours for rest of your academic work. That forty-five hours is about the same as a typical full-time job. If you work part time, time management skills are even more essential. These skills are still more important for part-time college students who work full time and commute or have a family. To succeed in college, virtually everyone has to develop effective strategies for dealing with time.

Many students begin college not knowing that two hours of studying for each course they are taking is needed, so don’t be surprised if you underestimated this number of hours also. Remember this is just an average amount of study time—you may need more or less for your own courses. To be safe, and to help ensure your success, add another five to ten hours a week for studying.

To reserve this study time, you may need to adjust how much time you spend in other activities. The Exercise below will help you figure out what your typical week should look like.

Time and Your Personality

People's attitudes toward time vary widely. One person seems to be always rushing around but actually gets less done than another person who seems unconcerned about time and calmly goes about the day. Since there are so many different “time personalities,” it’s important to realize how you approach time.

People who estimate too high often feel they don’t have enough time. They may have time anxiety and often feel frustrated. People at the other extreme, who often can’t account for how they use all their time, may have a more relaxed attitude. They may not actually have any more free time, but they may be wasting more time than they want to admit with less important things. Yet they still may complain about how much time they spend studying, as if there’s a shortage of time.

People also differ in how they respond to schedule changes. Some go with the flow and accept changes easily, while others function well only when following a planned schedule and may become upset if that schedule changes. If you do not react well to an unexpected disruption in your schedule, plan extra time for catching up if something throws you off. This is all part of understanding your time personality.

Another aspect of your time personality involves time of day. If you need to concentrate, such as when writing a class paper, are you more alert and focused in the morning, afternoon, or evening? Do you concentrate best when you look forward to a relaxing activity later on, or do you study better when you’ve finished all other activities? Do you function well if you get up early—or stay up late—to accomplish a task? How does that affect the rest of your day or the next day? Understanding this will help you better plan your study periods.

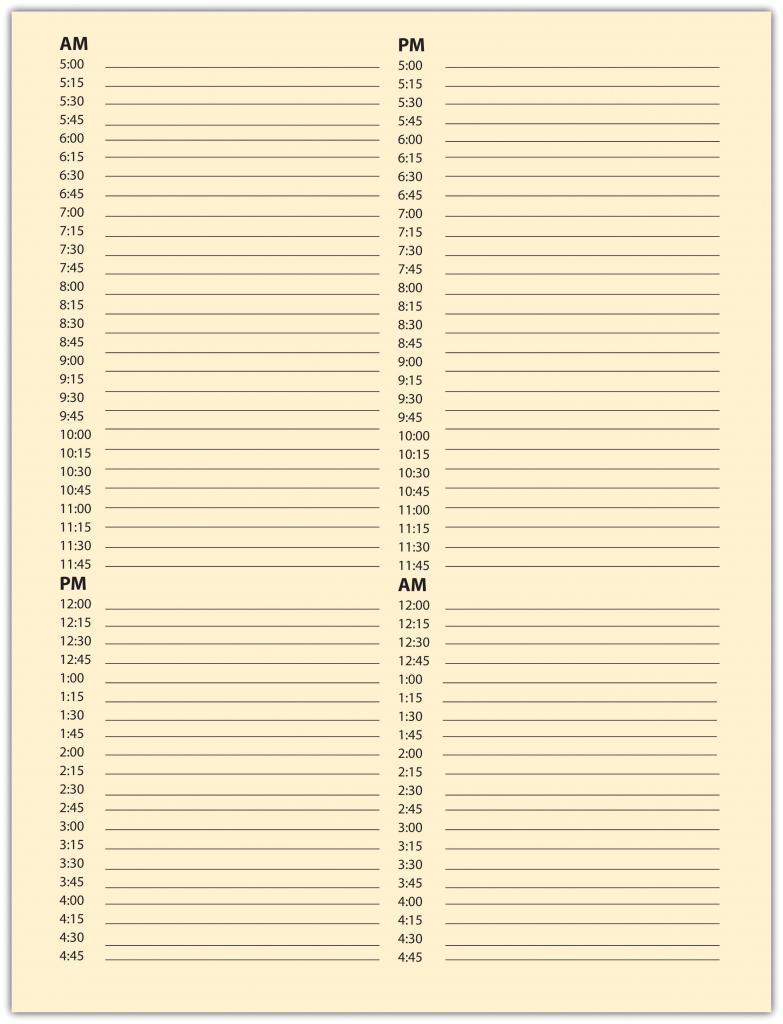

While you may not be able to change your “time personality,” you can learn to manage your time more successfully. The key is to be realistic. The best way to know how you spend your time is to record what you do all day in a time log (see Figure 2.4 “Daily Time Log” below) every day for a week, and then add that up. Every so often, fill in what you have been doing. Do this for a week before adding up the times; then enter the total hours into categories (i.e. chores, work, family, school, social media). You might be surprised that you spend a lot more time than you thought just hanging out with friends—or surfing the Web, playing around on social media, or any of the many other things people do. You might find that you study well early in the morning even though you thought you are a night person, or vice versa. You might learn how long you can continue at a specific task before needing a break.

If you have work and family responsibilities, you may already know where many of your hours go. Although we all wish we had “more time,” the important thing is what we do with the time we have. Time management strategies can help us better use the time we do have by creating a schedule that works for our own time personality.

Figure 2.4 Daily Time Log

Fixed Time vs. Free Time

Sometimes it helps to take a look at your time and divide it into two areas: fixed time and free time. Fixed time is time that you have committed to a certain area. It might be school, work, religion, recreation or family. There is no right or wrong to fixed time and everyone’s is different. Some people will naturally have more fixed time than others. Free time is just that—it is free. It can be used however you want to use it; it’s time you have available for activities you enjoy. Someone might work 9am-2pm, then have class 3pm-4:30pm, then have dinner with family 5pm-6pm, study 6pm-7pm and then have free time from 7pm-9pm. Take a look at a typical week for yourself. How much fixed time do you have? How much free time? How much fixed and free time would you like to have?

Laura Vanderkam’s TED Talk helps with perspective on free time.

Video: How to Gain Control of Your Free Time, Laura Vanderkam TED Talk

https://www.ted.com/talks/laura_vanderkam_how_to_gain_control_of_your_free_time

You must make time for the things that are most important to you. In order to make time, you may need to decide you will not do something else.

The ability to say “no” cannot be underestimated. It isn’t easy to say “no,” especially to family, friends and people that like you and whom you like. Most of us don’t want to say “no,” especially when we want to help. But if we always do what others want, we won’t accomplish the things that we want—the things that are most important to us.

Ask yourself:

- What am I doing that doesn’t need to be done?

- What can I do more efficiently?

Have you ever ordered an appetizer, salad, beverage or bread, then felt full halfway through your entree? In situations like this many people claim, “my eyes were bigger than my stomach.” This is also true with planning and goal setting. It may be that your plan is bigger than the day. Experiment with what you want to accomplish and what is realistic. The better you can accurately predict what you can and will accomplish and how long it will take, the better you can plan, and the more successful you will be.

Typically, most college students do actually have plenty of time for their studies without losing sleep or giving up their social life. But you may have less time for discretionary activities than in the past. Something, somewhere has to give. That’s part of time management—and why it’s important to keep your goals and priorities in mind. The other part is to learn how to use the hours you do have as effectively as possible, especially the study hours. For example, if you’re a typical college freshman who plans to study for three hours in an evening but then procrastinates, gets caught up in a conversation, loses time to checking e-mail and text messages, and listens to loud music while reading a textbook, then maybe you actually spent four hours “studying” but got only two hours of actual work done. So you end up behind and feeling like you’re still studying way too much. The goal of time management is to actually get three hours of studying done in three hours and have time for your life as well.

Special note for students who work. You may have almost no discretionary time at all left after all your “must-do” activities. If so, you may have overextended yourself—a situation that inevitably will lead to problems. You can’t sleep two hours less every night for the whole school year, for example, without becoming ill or unable to concentrate well on work and school. It is better to recognize this situation now rather than set yourself up for a very difficult term and possible failure. If you cannot cut the number of hours for work or other obligations, see your academic advisor right away. It is better to take fewer classes and succeed than to take more classes than you have time for and risk failure.

Time Management Strategies for Success

Following are some strategies you can begin using immediately to make the most of your time:

- Prepare to be successful. When planning ahead for studying, think yourself into the right mood. Focus on the positive. “When I get these chapters read tonight, I’ll be ahead in studying for the next test, and I’ll also have plenty of time tomorrow to do X.” Visualize yourself studying well!

- Use your best—and most appropriate—time of day. Different tasks require different mental skills. Some kinds of studying you may be able to start first thing in the morning as you wake, while others need your most alert moments at another time.

- Break up large projects into small pieces. Whether it’s writing a paper for class, studying for a final exam, or reading a long assignment or full book, students often feel daunted at the beginning of a large project. It’s easier to get going if you break it up into stages that you schedule at separate times—and then begin with the first section that requires only an hour or two.

- Do the most important studying first. When two or more things require your attention, do the more crucial one first. If something happens and you can’t complete everything, you’ll suffer less if the most crucial work is done.

- If you have trouble getting started, do an easier task first. Like large tasks, complex or difficult ones can be daunting. If you can’t get going, switch to an easier task you can accomplish quickly. That will give you momentum, and often you feel more confident tackling the difficult task after being successful in the first one.

- If you’re feeling overwhelmed and stressed because you have too much to do, revisit your time planner. Sometimes it’s hard to get started if you keep thinking about other things you need to get done. Review your schedule for the next few days and make sure everything important is scheduled, then relax and concentrate on the task at hand.

- If you’re really floundering, talk to someone. Maybe you just don’t understand what you should be doing. Talk with your instructor or another student in the class to get back on track.

- Take a break. We all need breaks to help us concentrate without becoming fatigued and burned out. As a general rule, a short break every hour or so is effective in helping recharge your study energy. Get up and move around to get your blood flowing, clear your thoughts, and work off stress.

- Use unscheduled times to work ahead. You’ve scheduled that hundred pages of reading for later today, but you have the textbook with you as you’re waiting for the bus. Start reading now, or flip through the chapter to get a sense of what you’ll be reading later. Either way, you’ll save time later. You may be amazed how much studying you can get done during downtimes throughout the day.

- Keep your momentum. Prevent distractions, such as multitasking, that will only slow you down. Check for messages, for example, only at scheduled break times.

- Reward yourself. It’s not easy to sit still for hours of studying. When you successfully complete the task, you should feel good and deserve a small reward. A healthy snack, a quick video game session, or social activity can help you feel even better about your successful use of time.

- Just say no. Always tell others nearby when you’re studying, to reduce the chances of being interrupted. Still, interruptions happen, and if you are in a situation where you are frequently interrupted by a family member, spouse, roommate, or friend, it helps to have your “no” prepared in advance: “No, I really have to be ready for this test” or “That’s a great idea, but let’s do it tomorrow—I just can’t today.” You shouldn’t feel bad about saying no—especially if you told that person in advance that you needed to study.

- Have a life. Never schedule your day or week so full of work and study that you have no time at all for yourself, your family and friends, and your larger life.

- Use a calendar planner and daily to-do list. We’ll look at these time management tools in the next section.

Time Management Tips for Students Who Work

If you’re both working and taking classes, you seldom have large blocks of free time. Avoid temptations to stay up very late studying, for losing sleep can lead to a downward spiral in performance at both work and school. Instead, try to follow these guidelines:

- If possible, adjust your work or sleep hours so that you don’t spend your most productive times at work. If your job offers flex time, arrange your schedule to be free to study at times when you perform best.

- Try to arrange your class and work schedules to minimize commuting time. If you are a part-time student taking two classes, taking classes back-to-back two or three days a week uses less time than spreading them out over four or five days. Working four ten-hour days rather than five eight-hour days reduces time lost to travel, getting ready for work, and so on.

- If you can’t arrange an effective schedule for classes and work, consider online courses that allow you to do most of the work on your own time.

- Use your daily and weekly planner conscientiously. Any time you have thirty minutes or more free, schedule a study activity.

- Consider your “body clock” when you schedule activities. Plan easier tasks for those times when you’re often fatigued and reserve alert times for more demanding tasks.

- Look for any “hidden” time potentials. Maybe you prefer the thirty-minute drive to work over a forty-five-minute train ride. But if you can read on the train, that’s a gain of ninety minutes every day at the cost of thirty minutes longer travel time. An hour a day can make a huge difference in your studies.

- Can you do quick study tasks during slow times at work? Take your class notes with you and use even five minutes of free time wisely.

- Remember your long-term goals. You need to work, but you also want to finish your college program. If you have the opportunity to volunteer for some overtime, consider whether it’s really worth it. Sure, the extra money would help, but could the extra time put you at risk for not doing well in your classes?

- Be as organized on the job as you are academically. Use your planner and to-do list for work matters, too. The better organized you are at work, the less stress you’ll feel—and the more successful you’ll be as a student also.

- If you have a family as well as a job, your time is even more limited. In addition to the previous tips, try some of the strategies that follow.

Time Management Tips for Students with Family

Living with family members often introduces additional time stresses. You may have family obligations that require careful time management. Use all the strategies described earlier, including family time in your daily plans the same as you would hours spent at work. Don’t assume that you’ll be “free” every hour you’re home, because family events or a family member’s need for your assistance may occur at unexpected times. Schedule your important academic work well ahead and in blocks of time you control. See also the earlier suggestions for controlling your space: you may need to use the library or another space to ensure you are not interrupted or distracted during important study times.

Students with their own families are likely to feel time pressures. After all, you can’t just tell your partner or kids that you’ll see them in a couple years when you’re not so busy with job and college! In addition to all the planning and study strategies discussed so far, you also need to manage your family relationships and time spent with family. While there’s no magical solution for making more hours in the day, even with this added time pressure there are ways to balance your life well:

- Talk everything over with your family. If you’re going back to school, your family members may not have realized changes will occur. Don’t let them be shocked by sudden household changes. Keep communication lines open so that your partner and children feel they’re together with you in this new adventure. Eventually you will need their support.

- Work to enjoy your time together, whatever you’re doing. You may not have as much time together as previously, but cherish the time you do have—even if it’s washing dishes together or cleaning house. If you’ve been studying for two hours and need a break, spend the next ten minutes with family instead of checking e-mail or watching television. Ultimately, the important thing is being together, not going out to movies or dinners or the special things you used to do when you had more time. Look forward to being with family and appreciate every moment you are together, and they will share your attitude.

- Combine activities to get the most out of time. Don’t let your children watch television or play video games off by themselves while you’re cooking dinner, or you may find you have only twenty minutes family time together while eating. Instead, bring the family together in the kitchen and give everyone something to do. You can have a lot of fun together and share the day’s experiences, and you won’t feel so bad then if you have to go off and study by yourself.

- Share the load. Even children who are very young can help with household chores to give you more time. Attitude is everything: try to make it fun, the whole family pulling together—not something they “have” to do and may resent, just because Mom or Dad went back to school. (Remember, your kids will reach college age someday, and you want them to have a good attitude about college.) As they get older, they can do their own laundry, cook meals, and get themselves off to school, and older teens can run errands and do the grocery shopping. They will gain in the process by becoming more responsible and independent.

- Schedule your study time based on family activities. If you face interruptions from young children in the early evening, use that time for something simple like reviewing class notes. When you need more quiet time for concentrated reading, wait until they’ve gone to bed.

- Be creative with child care. Usually options are available, possibly involving extended family members, sitters, older siblings, cooperative child care with other adult students, as well as child-care centers. After a certain age, you can take your child along to campus when you attend an evening course, if there is somewhere the child can quietly read. At home, let your child have a friend over to play with. Network with other older students and learn what has worked for them. Explore all possibilities to ensure you have time to meet your college goals. And don’t feel guilty: “day care babies” grow up just as healthy psychologically as those raised in the home full time.

Time Management Tips for Student Athletes

Student athletes often face unique time pressures because of the amount of time required for training, practice, and competition. During some parts of the year, athletics may involve as many hours as a full-time job. The athletic schedule can be grueling, involving weekend travel and intensive blocks of time. You can be exhausted after workouts or competitions, affecting how well you can concentrate on studies thereafter. Students on athletic scholarships often feel their sport is their most important reason for being in college, and this priority can affect their attitudes toward studying. For all of these reasons, student athletes face special time management challenges. Here are some tips for succeeding in both your sport and academics:

- Realize that even if your sport is more important to you, you risk everything if you don’t also succeed in your academics. Failing one class in your first year won’t get you kicked out, but you’ll have to make up that class—and you’ll end up spending more time on the subject than if you’d studied more to pass it the first time.

- It’s critical to plan ahead. If you have a big test or a paper due the Monday after a big weekend game, start early. Use your weekly planner to plan well in advance, making it a goal, for example, to have the paper done by Friday—instead of thinking you can magically get it done Sunday night after victory celebrations. Working ahead will also free your mind to focus better on your sport.

- Accept that you have two priorities—your sport and your classes—and that both come before your social life. That’s just how it is—what you have accepted in your choice to be a college athlete. If it helps, think of your classes as your job; you have to “go to study” the same as others “go to work.”

- Use your planner to take advantage of any downtime you have during the day between classes and at lunch. Other students may seem to have the luxury of studying during much of the afternoon when you’re at practice, and maybe they can get away with hanging out between classes, but you don’t have that time available, at least not during the season. You need to use all the time you can find to keep up with your studying.

- Stay on top of your courses. If you allow yourself to start slipping behind, maybe telling yourself you’ll have more time later on to catch up, just the opposite will happen. Once you get behind, you’ll lose momentum and find it more difficult to understand what’s going on the class. Eventually the stress will affect your athletic performance also.

- Get help when you need it. Many athletic departments offer tutoring services or referrals for extra help. But don’t wait until you’re at risk for failing a class before seeking help. A tutor won’t take your test or write your paper for you—they can only help you focus in to use your time productively in your studies. You still have to want to succeed.

Calendar Planners and To-Do Lists

Calendar planners and to-do lists are effective ways to organize your time. Many types of academic planners are commercially available (check your college bookstore), or you can make your own. Some people like a page for each day, and some like a week at a time. Some use computer calendars and planners. Almost any system will work well if you use it consistently.

Some college students think they don’t need to actually write down their schedule and daily to-do lists. They’ve always kept it in their head before, so why write it down in a planner now? Some first-year students were talking about this one day in a study group, and one bragged that she had never had to write down her calendar because she never forgot dates. Another student reminded her how she’d forgotten a pre-registration date and missed taking a course she really wanted because the class was full by the time she went online to register. “Well,” she said, “except for that time, I never forget anything!” Of course, none of us ever forgets anything—until we do.

Calendars and planners help you look ahead and write in important dates and deadlines so you don’t forget. But it’s just as important to use the planner to schedule your own time, not just deadlines. For example, you’ll learn later that the most effective way to study for an exam is to study in several short periods over several days. You can easily do this by choosing time slots in your weekly planner over several days that you will commit to studying for this test. You don’t need to fill every time slot, or to schedule every single thing that you do, but the more carefully and consistently you use your planner, the more successfully will you manage your time.

But a planner cannot contain every single thing that may occur in a day. We’d go crazy if we tried to schedule every telephone call, every e-mail, every bill to pay, every trip to the grocery store. For these items, we use a to-do list, which may be kept on a separate page in the planner.

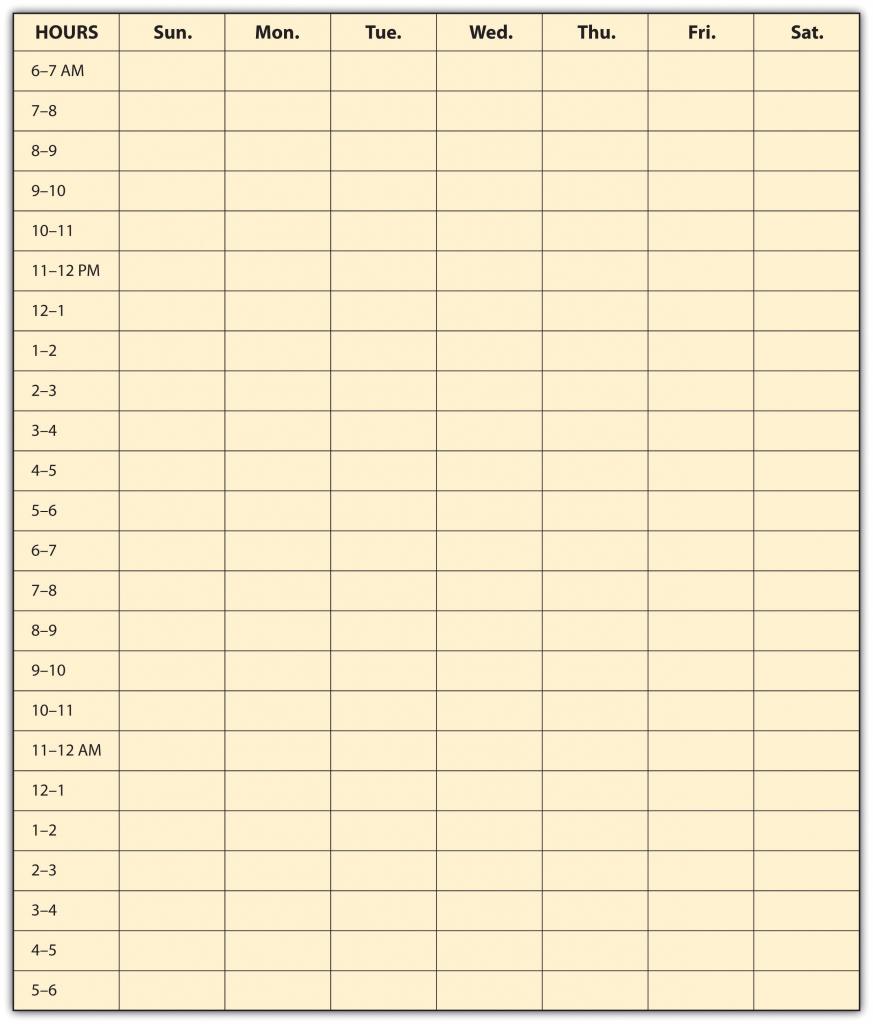

Check the example of a weekly planner form in Figure 2.5 “Weekly Planner” below. (You can copy this page and use it to begin your schedule planning. By using this first, you will find out whether these time slots are big enough for you or whether you’d prefer a separate planner page for each day.) Fill in this planner form for next week. First write in all your class meeting times; your work or volunteer schedule; and your usual hours for sleep, family activities, and any other activities at fixed times. Don’t forget time needed for transportation, meals, and so on. Your first goal is to find all the blocks of “free time” that are left over.

Remember that this is an academic planner. Don’t try to schedule in everything in your life—this is to plan ahead to use your study time most effectively.

Next, check the syllabus for each of your courses and write important dates in the planner. If your planner has pages for the whole term, write in all exams and deadlines. Use red ink or a highlighter for these key dates. Write them in the hour slot for the class when the test occurs or when the paper is due, for example. (If you don’t yet have a planner large enough for the whole term, use Figure 2.5 “Weekly Planner” and write any deadlines for your second week in the margin to the right. You need to know what’s coming next week to help schedule how you’re studying this week.)

Figure 2.5 Weekly Planner

Remember that for every hour spent in class, plan an average of two hours studying outside of class. These are the time periods you now want to schedule in your planner. These times change from week to week, with one course requiring more time in one week because of a paper due at the end of the week and a different course requiring more the next week because of a major exam. Make sure you block out enough hours in the week to accomplish what you need to do. As you choose your study times, consider what times of day you are at your best and what times you prefer to use for social or other activities.

Don’t try to micro manage your schedule. Don’t try to estimate exactly how many minutes you’ll need two weeks from today to read a given chapter in a given textbook. Instead, just choose the blocks of time you will use for your studies. Don’t yet write in the exact study activity—just reserve the block. Next, look at the major deadlines for projects and exams that you wrote in earlier. Estimate how much time you may need for each and work backward on the schedule from the due date. For example, you have a short paper due on Friday. You determine that you’ll spend ten hours total on it, from initial brainstorming and planning through to drafting and revising. Since you have other things also going on that week, you want to get an early start; you might choose to block an hour a week ahead on Saturday morning, to brainstorm your topic, and jot some preliminary notes. Monday evening is a good time to spend two hours on the next step or prewriting activities. Since you have a lot of time open Tuesday afternoon, you decide that’s the best time to reserve to write the first draft; you block out three or four hours. You make a note on the schedule to leave time open that afternoon to see your instructor during office hours in case you have any questions on the paper; if not, you’ll finish the draft or start revising. Thursday, you schedule a last block of time to revise and polish the final draft due tomorrow.

If you’re surprised by this amount of planning, you may be the kind of student who used to think, “The paper’s due Friday—I have enough time Thursday afternoon, so I’ll write it then.” What’s wrong with that? First, college work is more demanding than many first-year students realize, and the instructor expects higher-quality work than you can churn out quickly without revising. Second, if you are tired on Thursday because you didn’t sleep well Wednesday night, you may be much less productive than you hoped—and without a time buffer, you’re forced to turn in a paper that is not your best work.

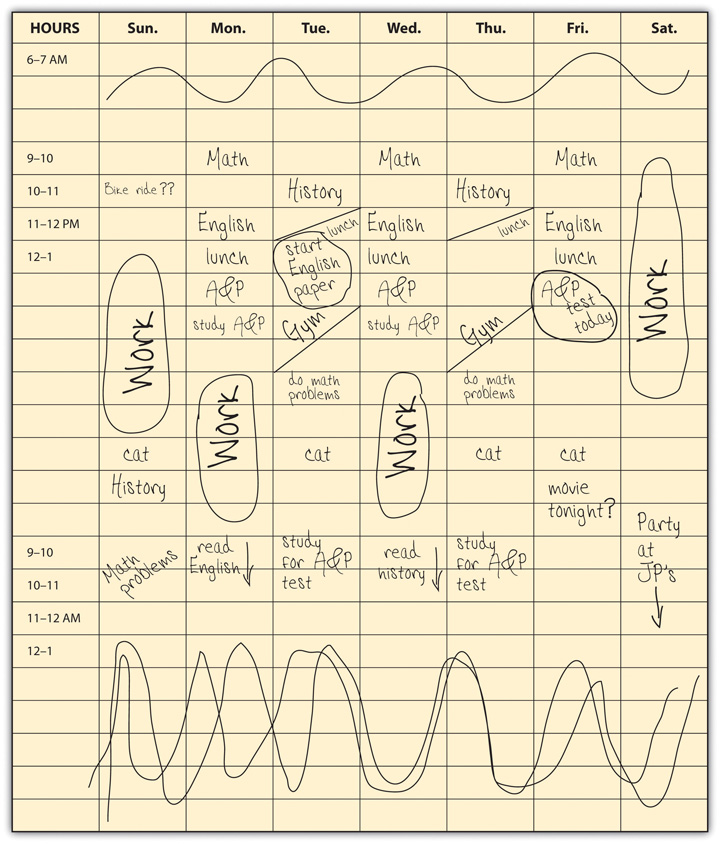

Figure 2.6 “Example of a Student’s Weekly Planner Page with Class Times and Important Study Sessions” shows what one student’s schedule looks like for a week. This is intended only to show you one way to block out time—you’ll quickly find a way that works best for you.

Figure 2.6 Example of a Student’s Weekly Planner Page with Class Times and Important Study Sessions

Here are some more tips for successful schedule planning:

- Studying is often most effective immediately after a class meeting. If your schedule allows, block out appropriate study time after class periods.

- Be realistic about time when you make your schedule. If your class runs to four o’clock and it takes you twenty minutes to wrap things up and reach your study location, don’t figure you’ll have a full hour of study between four o’clock and five o’clock.

- Don’t overdo it. Few people can study four or five hours nonstop, and scheduling extended time periods like that may just set you up for failure.

- Schedule social events that occur at set times, but just leave holes in the schedule for other activities. Enjoy those open times and recharge your energies!

- Try to schedule some time for exercise at least three days a week.

- Plan to use your time between classes wisely. If three days a week you have the same hour free between two classes, what should you do with those three hours? Maybe you need to eat, walk across campus, or run an errand. But say you have an average forty minutes free at that time on each day. Instead of just frittering the time away, use it to review your notes from the previous class or for the coming class or to read a short assignment. Over the whole term, that forty minutes three times a week adds up to a lot of study time.

- If a study activity is taking longer than you had scheduled, look ahead and adjust your weekly planner to prevent the stress of feeling behind.

- If you maintain your schedule on your computer or smartphone, it’s still a good idea to print and carry it with you. Don’t risk losing valuable study time if you’re away from the device.

- If you’re not paying close attention to everything in your planner, use a colored highlighter to mark the times blocked out for really important things.

- When following your schedule, pay attention to starting and stopping times. If you planned to start your test review at four o’clock after an hour of reading for a different class, don’t let the reading run long and take time away from studying for the test.

Your Daily To-Do List

People use to-do lists in different ways, and you should find what works best for you. As with your planner, consistent use of your to-do list will make it an effective habit.

Some people prefer not to carry their planner everywhere but instead copy the key information for the day onto a to-do list. Using this approach, your daily to-do list starts out with your key scheduled activities and then adds other things you hope to do today.

Some people use their to-do list only for things not on their planner, such as short errands, phone calls or e-mail, and the like. This still includes important things—but they’re not scheduled out for specific times.

Although we call it a daily list, the to-do list can also include things you may not get to today but don’t want to forget about. Keeping these things on the list, even if they’re a low priority, helps ensure that eventually you’ll get to it.

Start every day with a fresh to-do list written in a special small notebook or on a clean page in your planner. Check your planner for key activities for the day and check yesterday’s list for items remaining.

Some items won’t require much time, but other activities such as assignments will. Include a time estimate for these so that later you can do them when you have enough free time. If you finish lunch and have twenty-five minutes left before your next class, what things on the list can you do now and check off?

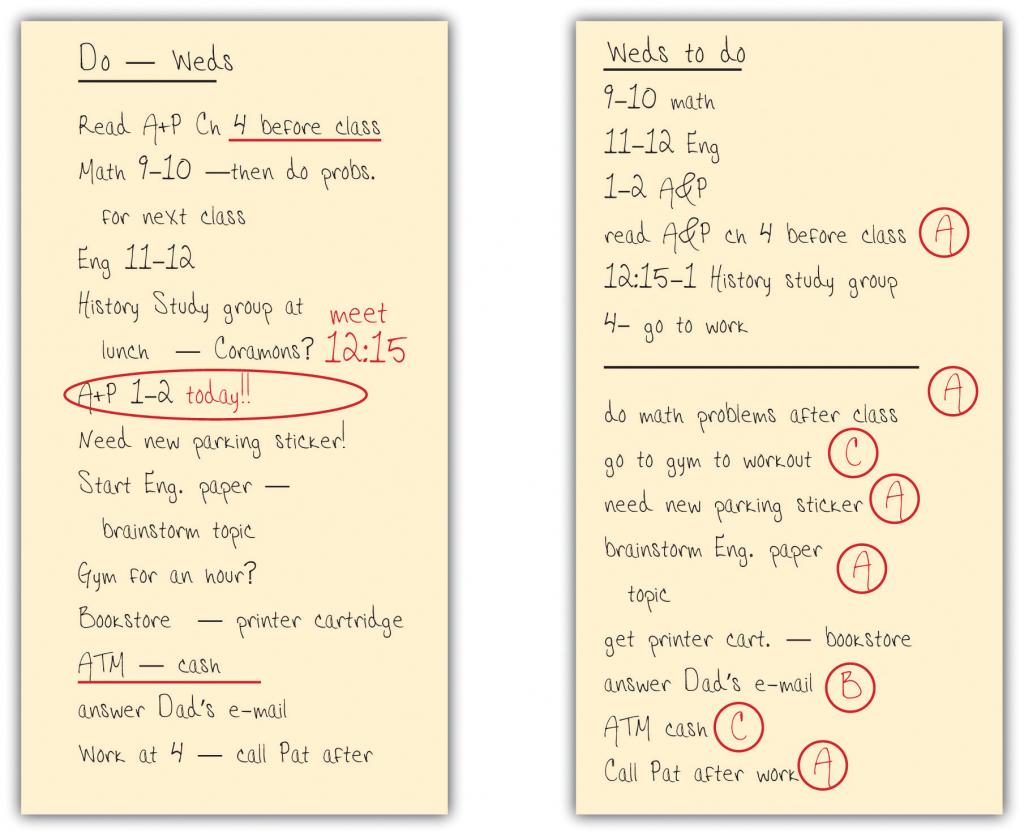

Finally, use some system to prioritize things on your list. Some students use a 1, 2, 3 or A, B, C rating system for importance. Others simply highlight or circle items that are critical to get done today. Figure 2.7 “Examples of Two Different Students’ To-Do Lists” shows two different to-do lists—each very different but each effective for the student using it.

Figure 2.7 Examples of Two Different Students’ To-Do Lists

Use whatever format works best for you to prioritize or highlight the most important activities.

Here are some more tips for effectively using your daily to-do list:

- Be specific: “Read history chapter 2 (30 pages)”—not “History homework.”

- Put important things high on your list where you’ll see them every time you check the list.

- Make your list at the same time every day so that it becomes a habit.

- Don’t make your list overwhelming. If you added everything you eventually need to do, you could end up with so many things on the list that you’d never read through them all. If you worry you might forget something, write it in the margin of your planner’s page a week or two away.

- Use your list. Lists often include little things that may take only a few minutes to do, so check your list any time during the day you have a moment free.

- Cross out or check off things after you’ve done them—doing this becomes rewarding.

- Don’t use your to-do list to procrastinate. Don’t pull it out to find something else you just “have” to do instead of studying!

Identifying, Organizing and Prioritizing Goals

The universal challenge of time is that there are more things that we want to do and not enough time to do them.

I talk to students frequently who have aspirations, dreams, goals and things they want to accomplish. Similarly, I ask students to list their interests at the beginning of each of my classes and there is never a shortage of items. But I often talk to students who are discouraged by the length of time it is taking them to complete a goal (completing their education, reaching their career goal, buying a home, getting married, etc.). And every semester there are students that drop classes because they have taken on too much or they are unable to keep up with their class work because they have other commitments and interests. There is nothing wrong with other commitments or interests. On the contrary, they may bring joy and fulfillment, but do they get in the way of your educational goal(s)? For instance, if you were to drop a class because you required surgery, needed to take care of a sick family member or your boss increased your work hours, those may be important and valid reasons to do so. If you were to drop a class because you wanted to binge watch Grey’s Anatomy, play more Minecraft, or spend more time on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, you may have more difficulty justifying that decision, but it is still your decision to make. Sometimes students do not realize the power they have over the decisions they make and how those decisions can affect their ability to accomplish the goals they set for themselves.

I am no exception. I have a long list of things that I want to accomplish today, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year and in my lifetime. I have many more things on my list to complete than the time that I will be alive.

Identifying Goals

Recently, there has been a lot of attention given to the importance of college students identifying their educational objective and their major as soon as possible. Some high schools are working with students to identify these goals earlier. If you are interested in career identification, you may wish to look into a career decision making course offered by your college. You may also wish to make an appointment with a counselor, and/or visit your college’s Career Center and/or find a career advice book such as What Color is Your Parachute? by Richard N. Bolles.

Goal identification is a way to allow us to keep track of what we would like to accomplish as well as a mechanism to measure how successful we are at achieving our goals. This video gives modern practical advice about the future career market.

Video: Success in the New Economy, Kevin Fleming and Brian Y. Marsh, Citrus College:

How To Start Reaching Your Goals

Without goals, we aren’t sure what we are trying to accomplish, and there is little way of knowing if we are accomplishing anything. If you already have a goal-setting plan that works well for you, keep it. If you don’t have goals, or have difficulty working towards them, I encourage you to try this.

Make a list of all the things you want to accomplish for the next day. Here is a sample to do list:

- Go to grocery store

- Go to class

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Social media

- Study

- Eat lunch with friend

- Work

- Watch TV

- Text friends

Your list may be similar to this one or it may be completely different. It is yours, so you can make it however you want. Do not be concerned about the length of your list or the number of items on it.

“Obstacles are things a person sees when he takes his eyes off his goal.” – E. Joseph Cossman

You now have the framework for what you want to accomplish the next day. Hang on to that list. We will use it again.

Now take a look at the upcoming week, the next month and the next year. Make a list of what you would like to accomplish in each of those time frames. If you want to go jet skiing, travel to Europe or get a bachelor’s degree: Write it down. Pay attention to detail. The more detail within your goals the better. Ask yourself: what is necessary to complete your goals?

With those lists completed, take into consideration how the best goals are created. Commonly called “SMART” goals, it is often helpful to apply criteria to your goals. SMART is an acronym for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely. Perform a web search on the Internet to find out more about “SMART” goals. Are your goals SMART goals? For example, a general goal would be, “Achieve an ‘A’ in my anatomy class.” But a specific goal would say, “I will schedule and study for one hour each day at the library from 2pm-3pm for my anatomy class in order to achieve an ‘A’ and help me gain admission to nursing school.”

Now revise your lists for the things you want to accomplish in the next week, month and year by applying the SMART goal techniques. The best goals are usually created over time and through the process of more than one attempt, so spend some time completing this. Do not expect to have “perfect” goals on your first attempt. Also, keep in mind that your goals do not have to be set in stone. They can change. And since over time things will change around you, your goals should also change.

Another important aspect of goal setting is accountability. Someone could have great intentions and set up SMART goals for all of the things they want to accomplish. But if they don’t work towards those goals and complete them, they likely won’t be successful. It is easy to see if we are accountable in short-term goals. Take the daily to-do list for example. How many of the things that you set out to accomplish, did you accomplish? How many were the most important things on that list? Were you satisfied? Were you successful? Did you learn anything for future planning or time management? Would you do anything differently? The answers to these questions help determine accountability.

Long-term goals are more difficult to create and it is more challenging for us to stay accountable. Think of New Year’s Resolutions. Gyms are packed and mass dieting begins in January. By March, many gyms are empty and diets have failed. Why? Because it is easier to crash diet and exercise regularly for short periods of time than it is to make long-term lifestyle and habitual changes.

Randy Pausch was known for his lecture called “The Last Lecture,” now a bestselling book. Diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer, Pausch passes along some of his ideas for best strategies for uses of time in his lesser known lecture on time management. I don’t believe there is someone better suited to teach about time management than someone trying to maximize their last year, months, weeks and days of their life.

Organizing Goals

Place all of your goals, plans, projects and ideas in one place. Why? It prevents confusion. We often have more than one thing going on at a time and it may be easy to become distracted and lose sight of one or more of our goals if we cannot easily access them. Create a goal notebook, goal poster, goal computer file—organize it any way you want—just make sure it is organized and that your goals stay in one place.

Break Goals into Small Steps

I ask this question of students in my classes: If we decided today that our goal was to run a marathon and then went out tomorrow and tried to run one, what would happen? Students respond with: (jokingly) “I would die,” or “I couldn’t do it.” How come? Because we might need training, running shoes, support, knowledge, experience and confidence—often this cannot be done overnight. But instead of giving up and thinking it’s impossible because the task is too big for which to prepare, it’s important to develop smaller steps or tasks that can be started and worked on immediately. Once all of the small steps are completed, you’ll be on your way to accomplishing your big goals.

What steps would you need to complete the following big goals?

- Buying a house

- Getting married

- Attaining a bachelor’s degree

- Destroying the Death Star

- Losing weight

Prioritizing Goals

Why is it important to prioritize? Let’s look back at the sample list. If I spent all my time completing the first seven things on the list, but the last three were the most important, then I would not have prioritized very well.

It would have been better to prioritize the list after creating it and then work on the items that are most important first. You might be surprised at how many students fail to prioritize.

After prioritizing, the sample list now looks like this:

- Go to class

- Work

- Study

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Eat lunch with friend

- Go to grocery store

- Text friends

- Social media

- Watch TV

One way to prioritize is to give each task a value. A = Task related to goals; B = Important—Have to do; C = Could postpone. Then, map out your day so that with the time available to you, work on your A goals first. You’ll now see below our list has the ABC labels. You will also notice a few items have changed positions based on their label. Keep in mind that different people will label things different ways because we all have different goals and different things that are important to us. There is no right or wrong here, but it is paramount to know what is important to you, and to know how you will spend the majority of your time with the things that are the most important to you.

A Go to class

A Study

A Exercise

B Work

B Pay bills

B Go to grocery store

C Eat lunch with friend

C Text friends

C Social media

C Watch TV

Do the Most Important Things First

You do not have to be a scientist to realize that spending your time on “C” tasks instead of “A” tasks won’t allow you to complete your goals. The easiest things to do and the ones that take the least amount of time are often what people do first. Checking Facebook or texting might only take a few minutes but doing it prior to studying means we’re spending time with a “C” activity before an “A” activity.

People like to check things off that they have done. It feels good. But don’t confuse productivity with accomplishment of tasks that aren’t important. You could have a long list of things that you completed, but if they aren’t important to you, it probably wasn’t the best use of your time.

Estimating Task Time

One of the biggest challenges I see college students have is accurately estimating how much time it will take to complete a task. We might think we’re going to be able to read an assigned chapter in an hour. But what if it takes three hours to read and understand the chapter? Having the skill to know how long a homework assignment will take is something that can be developed. But until we can anticipate it accurately, it is best to leave some time in our schedule in case it takes longer than we had anticipated.

We have a limited amount of time. Most of us cannot complete everything we wish to complete—either in a day or in a lifetime. We hear people say, “I wish there was more time” or “If there was more time, I would have done this.” We have enough time to do many of the things we wish to do. People run into difficulty when they spend time on things that are not the most important things for them.

“There’s never enough time to do all the nothing you want.” – Bill Watterson

Battling Procrastination

Procrastination is a way of thinking that lets one put off doing something that should be done now. This can happen to anyone at any time. It’s like a voice inside your head keeps coming up with these brilliant ideas for things to do right now other than studying: “I really ought to get this room cleaned up before I study” or “I can study anytime, but tonight’s the only chance I have to do X.” That voice is also very good at rationalizing: “I really don’t need to read that chapter now; I’ll have plenty of time tomorrow at lunch.…”

Procrastination is very powerful. Some people battle it daily, others only occasionally. Most college students procrastinate often, and about half say they need help avoiding procrastination. Procrastination can threaten one’s ability to do well on an assignment or test.

People procrastinate for different reasons. Some people are too relaxed in their priorities, seldom worry, and easily put off responsibilities. Others worry constantly, and that stress keeps them from focusing on the task at hand. Some procrastinate because they fear failure; others procrastinate because they fear success or are such perfectionists that they don’t want to let themselves down. Some are dreamers. Many different factors are involved, and there are different styles of procrastinating.

Just as there are different causes, there are different possible solutions for procrastination. Different strategies work for different people. The time management strategies described earlier can help you avoid procrastination. Because this is a psychological issue, some additional psychological strategies can also help:

- Since procrastination is usually a habit, accept that and work on breaking it as you would any other bad habit: one day at a time. Know that every time you overcome feelings of procrastination, the habit becomes weaker—and eventually you’ll have a new habit of being able to start studying right away.

- Schedule times for studying using a daily or weekly planner. Carry it with you and look at it often. Just being aware of the time and what you need to do today can help you get organized and stay on track.

- If you keep thinking of something else you might forget to do later (making you feel like you “must” do it now), write yourself a note about it for later and get it out of your mind.

- Counter a negative with a positive. If you’re procrastinating because you’re not looking forward to a certain task, try to think of the positive future results of doing the work.

- Counter a negative with a worse negative. If thinking about the positive results of completing the task doesn’t motivate you to get started, think about what could happen if you keep procrastinating. You’ll have to study tomorrow instead of doing something fun you had planned. Or you could fail the test. Some people can jolt themselves right out of procrastination.

- On the other hand, fear causes procrastination in some people—so don’t dwell on the thought of failing. If you’re studying for a test, and you’re so afraid of failing it that you can’t focus on studying and you start procrastinating, try to put things in perspective. Even if it’s your most difficult class and you don’t understand everything about the topic, that doesn’t mean you’ll fail, even if you may not receive an A or a B.

- Study with a motivated friend. Form a study group with other students who are motivated and won’t procrastinate along with you. You’ll learn good habits from them while getting the work done now.

- Keep a study journal. At least once a day write an entry about how you have used your time and whether you succeeded with your schedule for the day. If not, identify what factors kept you from doing your work. (Use the form at the end of this chapter.) This journal will help you see your own habits and distractions so that you can avoid things that lead to procrastination.

- Get help. If you really can’t stay on track with your study schedule, or if you’re always putting things off until the last minute, see a college counselor. They have lots of experience with this common student problem and can help you find ways to overcome this habit.

Licenses and Attributions:

Content previously copyrighted, published in Blueprint for Success in College: Indispensable Study Skills and Time Management Strategies (by Dave Dillon), now licensed as CC BY.

Tim Urban: Inside the Mind of a Master Procrastinator. Authored by TED.com Located at: https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_urban_inside_the_mind_of_a_master_procrastinator

License: CC-BY–NC–ND 4.0 International.

Kim Vanderkam: How to Gain Control of Your Free Time. Authored by TED.com Located at: https://www.ted.com/talks/laura_vanderkam_how_to_gain_control_of_your_free_time

License: CC-BY–NC–ND 4.0 International.

All rights reserved content:

Randy Pausch Lecture: Time Management. Authored by: Carnegie Mellon University. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTugjssqOT0 License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Success in the New Economy. Located at: https://vimeo.com/67277269 License: All Rights Reserved.

Adaptions: Reformatted, some content removed to fit a broader audience.

- Jeffery Young, “Homework? What Homework?,” Chronicle of High Education, 2002, A35-A37, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Ho...Homework-/2496. ↵

- “Advancing Student Success in the California Community Colleges,” California Community Colleges (California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office: Recommendations of the California Community Colleges Student Success Task Force, 2012), http://www.californiacommunitycolleges.cccco.edu/portals/0/executive/studentsuccesstaskforce/sstf_final_report_1-17-12_print.pdf. ↵

- J. Weissman, C. Bulakowski, and M.K. Jumisko, “Using Research to Evaluate Developmental Education Programs and Policies,” in Implementing Effective Policies for Remedial and Developmental Education: New Directions for Community Colleges, ed. J. M. Ignash (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997), 100, 73-80. ↵

- Beth Smith et al., “The Role of Counseling Faculty and Delivery of Counseling Services in the California Community Colleges,” (California: The Academic Senate for California Community Colleges). ↵