3.1: The Writing Process

- Page ID

- 20040

What is The Writing Process?

Donald M. Murray, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and educator, presented his important article, “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product,” in 1972. In the article, he criticizes writing instructors’ tendency to view student writing as “literature” and to focus our attentions on the “product” (the finished essay) while grading. The idea that students are producing finished works ready for close examination and evaluation by their instructor is fraught with problems because writing is really a process and arguably a process that is never finished.

Murray explains why writing is an ongoing process:

What is the process we [writing instructors] should teach? It is the process of discovery through language. It is the process of exploration of what we know and what we feel about what we know through language. It is the process of using language to learn about our world, to evaluate what we learn about our world, to communicate what we learn about our world. Instead of teaching finished writing, we should teach unfinished writing, and glory in its unfinishedness. (4)

You will find that many college writing instructors have answered Murray’s call to “teach writing as a process” and due to shifting our focus on process rather than product, you will find yourself spending a lot of time brainstorming, drafting, revising, and editing. Embracing writing as a process helps apprehensive writers see that writing is not only about grammatical accuracy or “being a good writer.”

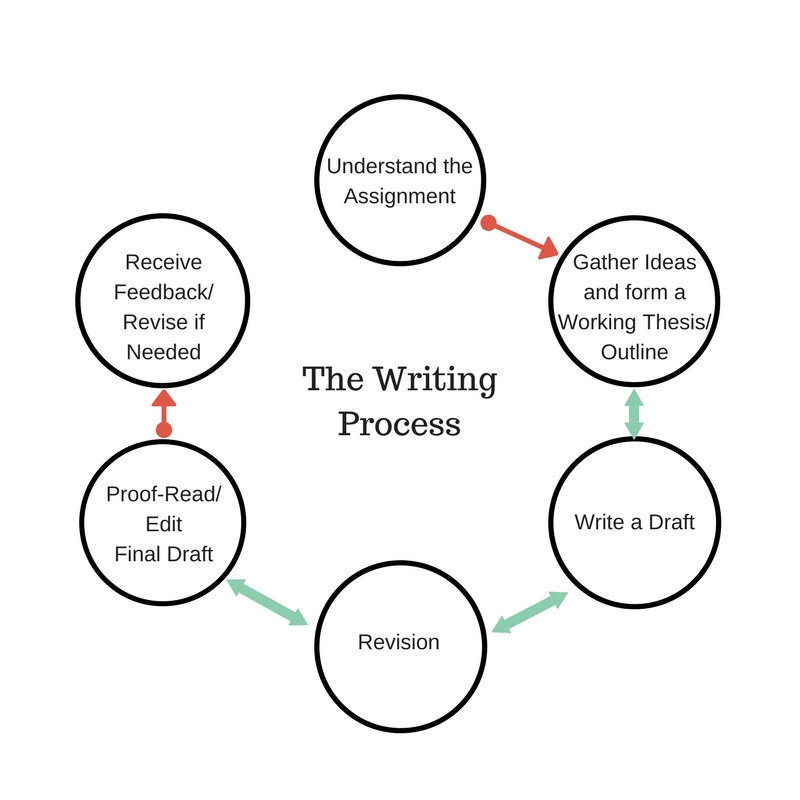

The Writing Process

“The Writing Process” image was created by Sarah M. Lacy

The most important lesson to understand about the writing process, is that it is recursive, meaning that you need to move back and forth between some or all of the steps; there are many ways to approach this process. Allowing yourself enough time to begin the assignment before it is due, will give you time to move from one step to the other, and back as needed. Perhaps the easiest way to think about this process is as a series of steps that you can move from one to the other and back again.

The Writing Process in 6 Steps

The following steps have been adapted from the work of Paul Eschholz and Alfred Rosa, found in their book Subject & Strategy. The authors focus on discussing writing as a series of steps that can be adapted to meet any writer’s needs; below, the steps have been modified to fit the needs of first-year writers. While reading through the steps below, remember that every writer has a unique approach to the writing process. The steps are presented in such a way that allow for any writer to understand the process as a whole, so that they can feel prepared when beginning a paper. Take special note of all the tips and guidance presented with each step, as well as suggested further reading, remembering that writing is a skill that needs practice: make sure to spend time developing your own connection to each step when writing a paper. The steps are as follows:

Step 1 – Understand the Assignment

Always read over the entire assignment sheet provided to you by your instructor. Think of this sheet as a contract; by accepting the sheet, you are agreeing to follow all guidelines and requirements that have been provided. This sheet is a direct communication from your instructor to you, laying out every expectation and requirement of an assignment. Follow each to ensure you are conducting and completing the assignment properly.

See Section 3.2 for a closer look at how to use an assignment sheet.

Step 2 – Gather Ideas and Form Working Thesis

Once you understand the assignment, you will need to collect information in order to understand your topic, and decide where you would like the paper to lead. This step can be conducted in various ways. Researching to build content knowledge is always a good place to start this step, so make sure to check out Chapter 8: The Research Process for a more specified look at various research methods.

After you have conducted some research begin brainstorming. You can do this in a variety of ways:

- Free Writing

- Listing ideas

- Generate a list of questions

- Clustering/ Mapping (creating a bubble chart)

- Create a basic outline

Then, you will want to formulate a Working Thesis. A working thesis is different than the thesis found in a final draft: it will not be specific nor as narrowed. Think of a working thesis as the general focus of the paper, helping to shape your research and brainstorming activities. As you will later spend ample time working and re-working a draft, allow yourself the freedom to revise this thesis as you become more familiar with your topic and purpose.

See Section 4.2: Creating a Thesis for more information on thesis statements.

Step 3 – Write a Draft

After completing Steps 1 and 2, you are ready to begin putting all parts and ideas together into a full length draft. It is important to remember that this is a first/rough draft, and the goal is to get all of your thoughts into writing, not generating a perfect draft. Do not get hung up with your language at this point, focus on the larger ideas and content.

Organization is a very important part of this step, and if you have not already composed an outline during Step 2, consider writing one now. The purpose of an outline is to create a logical flow of claims, evidence, and links before or during the drafting process; experiment with outlines to learn when and how they can work for you.

Outlines are great at helping you organize your outside sources, if you need to use some within a particular assignment. Start by generating a list of claims (or main ideas) to support your thesis, and decide which source belongs with each idea, knowing that you may (and should) use your sources more than once, with more than one claim.

Step 4 – Revise the Draft(s)

This is the step in which you are likely to spend the majority of your time. This section is different from simply “editing” or “proof reading” because you are looking for larger context issues; for example, this is when you need to check your topic sentences and transitions, make sure each claim matches the thesis statement, and so on. Return to Steps 1 and 2 as needed, to ensure you are on the right track and your draft is properly adhering to the guidelines of the assignment.

The revision portion of the writing process is also where you will need to make sure all of your paragraphs are fully developed as appropriate for the assignment. If you need to have outside sources present, this is when you will make sure that all are working properly together. If the assignment is a summary, this is when you will need to double check all paraphrasing to make sure it correctly represents the ideas and information of the source text.

It is likely that your professor will instruct you to complete Peer Editing. Learn more about this process in Section 3.4.

Step 5 – Proof-Read/Edit the Draft(s)

Once the larger content issues have been resolved and you are moving towards a final draft, work through the paper looking for grammar and style issues. This step is when you need to make sure that your tone is appropriate for the assignment (for example, you will need to make sure you have remained in a formal tone for all academic papers), that sources are properly integrated into your own work if your assignment calls for them, etc. Consider using the checklist offered in Section 3.6.

When entering the final step, go back to the assignment sheet, read it over once more in full, and then conduct a close reading. Doing this will help you to ensure you have completed all components of the assignment as per your instructor’s guidance.

Step 6 – Turn in the Draft, Receive Feedback, and Revise (if needed)

Once your draft is completed, turned in, and handed back with edits from your instructor, you may have an opportunity to revise, and turn in again to help raise your grade. As the goal of the FYW class is to improve your writing, this is an essential step to consider so that you get the most out of the course. Ask your instructor for more detail.

Works Cited

Eschholz, Paul and Alfred Rosa. Subject & Strategy: A Writer’s Reader. 11th ed., Bedford/St. Martin, 2007.