3.8: Main Ideas and Supporting Details

- Page ID

- 31307

Analyze Thesis or Main Ideas of Texts

Being able to identify the purpose and thesis of a text, while you’re reading it, takes practice. Questioning the text you’re reading is a good place to start. When trying to isolate the thesis, or main idea, of your reading material, consider these questions:

- What is the primary subject of this text?

- Is the author trying to inform me, or persuade me?

- What does the author think I need to know about this subject?

- Why does the author think I need to know about this subject?

Sometimes the answer to these questions will be very clearly stated in the text itself. Sometimes it is less obvious, and in those cases, the techniques on the following page will be useful.

Implicit vs. Explicit Main Idea/ Thesis Statements

According to author Pavel Zemliansky,

Arguments then, can be explicit and implicit, or implied. Explicit arguments contain noticeable and definable thesis statements and lots of specific proofs. Implicit arguments, on the other hand, work by weaving together facts and narratives, logic and emotion, personal experiences and statistics. Unlike explicit arguments, implicit ones do not have a one-sentence thesis statement. Instead, authors of implicit arguments use evidence of many different kinds in effective and creative ways to build and convey their point of view to their audience. Research is essential for creative effective arguments of both kinds.

Even if what you’re reading is an informative text, rather than an argumentative one, it might still rely on an implicit thesis statement. It might ask you to piece together the overall purpose of the text based on a series of content along the way.

The following video defines the key terms explicit and implicit, as they relate to thesis statements and other ideas present in what you read. It also introduces the excellent idea of the reading voice and the thinking voice that strong readers use as they work through a text.

To help keep you on your toes, the author of this video challenges you to find her spelling mistake in one of her cards along the way!

Explicit v. implicit. Authored by: Michele Armentrout. All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Take the quiz about implicit and explicit thesis statements to see how well you have understood the information.

Thesis and Topic Sentences

You’ll remember that the first step of the reading process, previewing, allows you to get a big-picture view of the document you’re reading. This way, you can begin to understand the structure of the overall text. A later step in the reading process, summarizing, allows you to encapsulate what a paragraph, section, or the whole document is about. When summarizing individual paragraphs, it’s likely that your summary ends up looking like a paraphrase of that paragraph’s topic sentence.

A paragraph is composed of multiple sentences focused on a single, clearly-defined topic. There should be exactly one main idea per paragraph, so whenever an author moves on to a new idea, he or she will start a new paragraph. For example, this paragraph defines what a paragraph is, and now we will start a new paragraph to deal with a new idea: how a paragraph is structured.

Paragraphs are actually organized much like persuasive papers are. Just like a paper has a thesis statement followed by a body of supportive evidence, paragraphs have a topic sentence followed by several sentences of support or explanation. If you look at this paragraph, for example, you will see that it starts with a clear topic sentence letting you know that paragraphs follow a structure similar to that of papers. The next sentence explains how a paragraph is like a paper, and then two more sentences show how this paragraph follows that structure. All of these sentences are clearly connected to the main idea.

The topic sentence of a paragraph serves two purposes: first, it lets readers know what the paragraph is going to be about; second, it highlights the connection between the present paragraph and the one that came before. The topic sentence of this paragraph explains to a reader what a topic sentence does, fulfilling the first function. It also tells you that this paragraph is going to talk about one particular aspect of the previous paragraph’s main idea: we are now moving from the general structure of the paragraph to the particular role of the topic sentence.

After the topic sentence introduces the main idea, the remainder of the sentences in a paragraph should support or explain this topic. These additional sentences might detail the author’s position on the topic. They might also provide examples, statistics, or other evidence to support that position. At the end of the paragraph, the author may include some sort of conclusion or a transition that sets up the next idea he or she will be discussing (for example, you can see this clearly in the last sentence of the third paragraph).

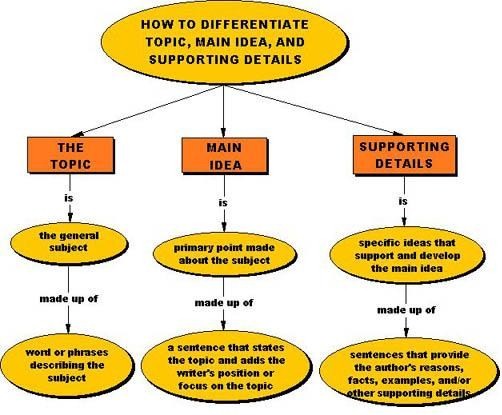

The Three Parts of a Paragraph

1) Topic

The topic is the subject of the paragraph. It can be:

- A few words long

- These words (or words related to the topic) are typically repeated throughout the paragraph

- Answers the question: What is this paragraph about?

2) Main Idea

This is the writer’s overall point. It can be:

- A complete sentence

- If stated in the paragraph, it’s called a “topic sentence”

- If unstated in the paragraph, the reader must figure it out (infer it) from details

- General enough to cover the more specific supporting details

- Usually (but not always!) near the beginning of the paragraph

- Answers the question: What is the overall point being made about the topic?”

3) Supporting Details

These are the details in the paragraph that support the main idea. They can be either major or minor supporting details.

Tips for Identifying Main Ideas

Although you are learning to put the main idea first in your own paragraphs, professional writers often don’t. Sometimes the first sentence of a paragraph provides background information, poses a question, or serves as a bridge from a previous paragraph. Don’t assume it is the main idea. Use these tips instead:

- Look for a general statement that appears to “cover” the other information.

- Figure out the general topic of the paragraph first. Then ask yourself, “What point is the writer trying to make about this topic?”

- Look for clue words. Main ideas sometimes have words such as “some” or plural nouns like “ways” or “differences” that signal a list of details to come.

- Check your guess! Once you think you’ve found the main idea, ask yourself:

- Is this statement supported by most of the other information?

- If I turn this statement into a question, does the other information answer it?

SPECIAL NOTE: Sometimes a main idea covers more than one paragraph. This may happen in newspaper articles or when the writer has a lot to say about one topic.

Difference Between the Topic and Main Idea

To understand the difference between a main idea and the topic, imagine that you are listening to your friends talk about their pets. The TV is on, so all you can make out are the name of their pets. If someone asked you what the topic was, you would say “pets.” But because you couldn’t hear the whole thing, you didn’t understand the “main idea” was whose pet was the best. The topic is very broad – the main idea is more specific. The sentences that follow in the paragraph exercise offer examples or descriptions to illustrate or explain the main idea. Note the reading-writing connection--while we are finding the main idea as readers, we will be using the main ideas to write topic sentences in paragraphs.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Read the following paragraph and then decide what the main idea is.

One myth about exercise is that if a woman lifts weights, she will develop muscles as large as a man’s. Without male hormones, however, a woman cannot increase her muscle bulk as much as a man’s. Another misconception about exercise is that it increases the appetite. Actually, regular exercise stabilizes the blood-sugar level and prevents hunger pangs. Some people also think that a few minutes of exercise a day or one session a week is enough, but at least three solid workouts a week are needed for muscular and cardiovascular fitness.

Choose the Main Idea:

a) Women who lift weights cannot become as muscular as men.

b) There are several myths about exercise.

c) Exercise is beneficial to everyone.

d) People use many different excuses to avoid exercising.

Explain why you did or did not choose each possible answer above.

a) ________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

b) ________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

c) ________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

d) ________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Read the following paragraph and then decide what the main idea is.

“To Sherlock Holmes she is always THE woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions, and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind. He was, I take it, the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen, but as a lover he would have placed himself in a false position. He never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer. They were admirable things for the observer--excellent for drawing the veil from men's motives and actions. But for the trained reasoner to admit such intrusions into his own delicate and finely adjusted temperament was to introduce a distracting factor which might throw a doubt upon all his mental results.“

- Answer

-

The main idea of this paragraph is the first sentence. The first sentence identifies the two characters that the rest of the paragraph is going to describe, and suggests at their relationship. Each sentence that follows either describes the woman, Sherlock Holmes, or how he felt about her or her effect on him.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Here is another example from the same story, see if you can find the main idea:

One night--it was on the twentieth of March, 1888--I was returning from a journey to a patient (for I had now returned to civil practice), when my way led me through Baker Street. As I passed the well-remembered door, which must always be associated in my mind with my wooing, and with the dark incidents of the Study in Scarlet, I was seized with a keen desire to see Holmes again, and to know how he was employing his extraordinary powers. His rooms were brilliantly lit, and, even as I looked up, I saw his tall, spare figure pass twice in a dark silhouette against the blind. He was pacing the room swiftly, eagerly, with his head sunk upon his chest and his hands clasped behind him. To me, who knew his every mood and habit, his attitude and manner told their own story. He was at work again.

a. One night--it was on the twentieth of March, 1888--I was returning from a journey to a patient (for I had now returned to civil practice), when my way led me through Baker Street.

b. As I passed the well-remembered door, which must always be associated in my mind with my wooing, and with the dark incidents of the Study in Scarlet, I was seized with a keen desire to see Holmes again, and to know how he was employing his extraordinary powers

c. His rooms were brilliantly lit, and, even as I looked up, I saw his tall, spare figure pass twice in a dark silhouette against the blind.

d. He was pacing the room swiftly, eagerly, with his head sunk upon his chest and his hands clasped behind him.

- Answer

-

The correct answer is a. The first sentence gives you the point-of-view, or who is the person explaining what is happening, and it lets you know that this person is going into a particular place. Each of the other sentences describes the place where he, Dr. Watson, entered, what it looked like, and who was in there.

B is not as strong a choice as a, because it refers to Study in Scarlet and Holmes’ powers, which are not described in the rest of the paragraph. Choice B is too specific to be the main idea of this paragraph. Choices c and d are not correct because they are describing Holmes’ actions, and his walking is not what the whole paragraph is about.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Let’s try one more. Read the following and select which one is the main idea from the list below:

“At three o'clock precisely I was at Baker Street, but Holmes had not yet returned. The landlady informed me that he had left the house shortly after eight o'clock in the morning. I sat down beside the fire, however, with the intention of awaiting him, however long he might be. I was already deeply interested in his inquiry, for, though it was surrounded by none of the grim and strange features which were associated with the two crimes which I have already recorded, still, the nature of the case and the exalted station of his client gave it a character of its own. Indeed, apart from the nature of the investigation which my friend had on hand, there was something in his masterly grasp of a situation, and his keen, incisive reasoning, which made it a pleasure to me to study his system of work, and to follow the quick, subtle methods by which he disentangled the most inextricable mysteries. So accustomed was I to his invariable success that the very possibility of his failing had ceased to enter into my head.”

a. At three o'clock precisely I was at Baker Street, but Holmes had not yet returned.

b. The landlady informed me that he had left the house shortly after eight o'clock in the morning.

c. I sat down beside the fire, however, with the intention of awaiting him, however long he might be

d. I was already deeply interested in his inquiry, for, though it was surrounded by none of the grim and strange features which were associated with the two crimes which I have already recorded, still, the nature of the case and the exalted station of his client gave it a character of its own.

- Answer

-

The way to figure out that the answer, this time, is d, is to look at each sentence that follows and ask, does this refer back to the location, Baker Street? Do they refer back to the landlady? Do they refer back to Dr. Watson’s waiting? Or, do they refer back to the case? They both refer back to the current investigation, by talking about Holmes’ way of untangling mysteries, and that Watson’s belief that the investigation would be a success.

The introduction to this paragraph may have thrown you off so be careful to read through the entire paragraph each time, and look at each sentence and its role within the paragraph. Mostly the main idea comes right up front – but not always!

Reading-Writing Connection: Thesis Statements

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

I. Develop a paragraph. Your paragraph must include the following:

- Between 7-9 sentences

- A main idea sentence

- Each sentence must be developed, and checked for correct spelling and grammar

- Have at least three of the four different types of sentences (simple, complex, compound, compound-complex)

- Attach your pre-writing practice after the paragraph, to identify which sentences are major and minor detail sentence

Supporting Details

Earlier we covered what a main idea sentence was: a sentence that names the topic, and allows the reader to understand the focus of the paragraph to follow. It is logical then that the rest of the sentences in the paragraph support the main idea sentence. Support means that they either explain something about the topic, or they offer an example.

We’ve examined the relationship between a text’s thesis statement and its overall organization through the idea of topic sentences in body paragraphs. But of course body paragraphs have a lot more “stuff” in them than just topic sentences. This section will examine in more detail what that “stuff” is made of.

First, watch this video that details the relationship between a topic sentence and supporting details, using the metaphor of a house. The video establishes the difference between major and minor details, which will be useful to apply in coming discussions. (The video has instrumental guitar for audio, but no spoken words, so it can be watched without sound if desired.)

Video: Supporting Details. Authored by: Mastering the Fundamentals of College Reading and Writing. All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

The following image shows the visual relationship between the overall thesis, topic sentences, and supporting ideas:

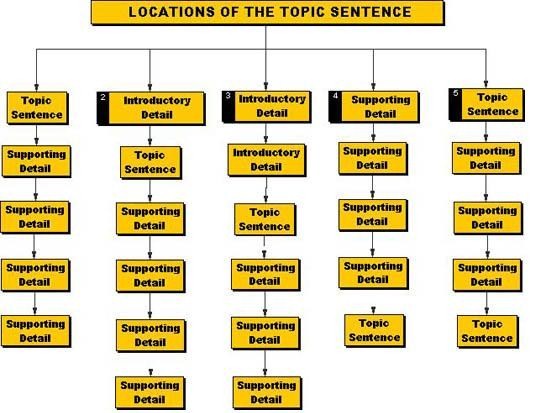

This next image shows where a topic sentence might reside in the paragraph, in relation to the rest of the supporting details:

In #5 of the sequence above, the topic sentence is rephrased between the opening and closing of the paragraph, to reinforce the concept more strongly.

Point, Illustration, Explanation (P.I.E.)

Many authors use the PIE format to structure their essays. PIE = point, illustration, explanation to structure their body paragraph and support their thesis. The point furthers a thesis or claim and is the same as the main idea, the illustration provides support for the point, and the explanation tells the audience why the evidence provided furthers the point and/or the thesis.

For example, in his argument against the +/- grading system at Radford, student-writer Tareq Hajj makes the Point that “Without the A+, students with high grades in the class would be less motivated to work even harder in order to increase their grades.”

He Illustrates with a quote from a professor who argues, “‘(students) have less incentive to try’” (Fesheraki, 2013).

Hajj then Explains that “not providing [the most motivated students] with additional motivation of a higher grade … is inequitable.”

Through his explanation, Hajj links back to his claim that “A plus-minus grading scale … should not be used at Radford University” because, as he explains, it is “inequitable.” The PIE structure of his paragraph has served to support his thesis.

All Claims Need Evidence

Ever heard the phrase “everyone is entitled to his opinion”? It is indeed true that people are free to believe whatever they wish. However, the mere fact that a person believes something is not an argument in support of a position. If a text’s goal is to communicate effectively, it must provide valid explanations and sufficient and relevant evidence to convince its audience to accept that position. In other words, “every author is entitled to his opinion, but no author is entitled to have his opinion go unchallenged.”

What are the types of evidence?

Any text should provide illustrations for each of its points, but it is especially important to provide reliable evidence in an academic argument. This evidence can be based on primary source material or data (the author’s own experience and/or interviews, surveys, polls, experiments, that she may have created and administered). Evidence can also stem from secondary source material or data (books, journals, newspapers, magazines, websites or surveys, experiments, statistics, polls, and other data collected by others).

Let’s say, for example, that you are reading an argument that college instructors should let students use cell phones in class. Primary source material might include a survey the author administered that asks students if policies forbidding cell phone usage actually stop them from using their phones in class. Secondary sources might include articles about the issue from Faculty Focus or The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Logos, Ethos, Pathos

Writers are generally most successful with their audiences when they can skillfully and appropriately balance the three core types of appeals. These appeals are referred to by their Greek names: logos (the appeal to logic), pathos (the appeal to emotion), and ethos (the appeal to authority). All of these are used in one way or another in your body paragraphs, particularly as it relates to the support or information in the paragraph.

Logical Appeals

Authors using logic to support their claims will include a combination of different types of evidence. These include the following:

- established facts

- case studies

- statistics

- experiments

- analogies and logical reasoning

- citation of recognized experts on the issue

Authoritative Appeals

Authors using authority to support their claims can also draw from a variety of techniques. These include the following:

- personal anecdotes

- illustration of deep knowledge on the issue

- citation of recognized experts on the issue

- testimony of those involved first-hand on the issue

Emotional Appeals

Authors using emotion to support their claims again have a deep well of options to do so. These include the following:

- personal anecdotes

- narratives

- impact studies

- testimony of those involved first-hand on the issue

As you can see, there is some overlap on these lists. One technique might work simultaneously on multiple levels.

Most texts rely on one of the three as the primary method of support, but may also draw upon one or two others at the same time.

Check your understanding of supporting details by doing this quiz.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Read the paragraph below and find the main idea and supporting details.

My parents were very strict when I was growing up. My mother in particular was always correcting my behavior. One day when I forgot to look both ways when I was crossing the street, my mother made me go back home; she said that I could not go out at all if I could not be safe. My father was more concerned with my grades. Every night he would make me go to my room before I could watch television.

Answer

-

Let’s examine the pattern for this paragraph. The first sentence (1) presents the main idea, that my parents were strict. The second sentence (2) explains what I mean by “strict,” by saying that my mother was strict in correcting my behavior. The third sentence (3) offers an example of how she would correct my behavior. The fourth sentence (4) explains further, that my father was strict when it came to schoolwork, and then the fifth sentence (5) offers an example of how he was strict.

If we were going to diagram the paragraph above, it would look like this:

MAIN IDEA

EXPLAIN (2)-___________________EXPLAIN (4)

EXAMPLE (3) EXAMPLE (5)

Major and Minor Supporting Details

One way to talk about whether a sentence directly supports the main idea (the second level), or indirectly supports the main idea (the third level) is to call them MAJOR detail sentences or MINOR detail sentences. Major details directly explain something about the topic, while minor details offer examples for the Major detail that came right before.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Read the paragraphs, and then identify each sentence as either a

main idea, a major detail, or a minor detail sentence.

Single parents have to overcome many obstacles to return to school. If

the child is very young, finding quality babysitting can be difficult. Many

babysitters are unreliable and that can mean that the parent has to miss

many classes, which can hurt their grades. It is also hard to find enough

time to study. Children require a lot of attention and are also noisy, and

that can interfere with a parent's ability to complete their homework.

Finally, raising children is expensive. Many single parents discover that

they can’t meet the costs of both raising children and paying for tuition,

books, and fees.

Sentence #1:

Sentence #2:

Sentence #3:

Sentence #4:

Sentence #5:

Sentence #6:

Sentence #7:

My grandmother turned 70 last year and celebrated by going skydiving.

She said she always wanted to try and figured it was now or never. Many

people think that when you get older you can no longer do fun things, but

this is not true. The senior center in town offers dance lessons and also

takes groups to the art museum. The classes are always full because so

many people want to try new things. Towns are even developing senior

living communities around activities such as golf and tennis. Those

communities are very popular because people like to live with others who

share their interests.

Sentence #1:

Sentence #2:

Sentence #3:

Sentence #4:

Sentence #5:

Sentence #6:

Sentence #7

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Below you will find several main idea sentences. Provide appropriate supporting sentences following the pattern of Major-Minor-Major-

Minor.

1. It is not a good idea to watch a lot of television.

Major:

Minor:

Major:

Minor:

2. Coaches have good reasons to be firm with the players on their team.

Major:

Minor:

Major:

Minor:

3. Many people believe it is a bad idea to spank children.

Major:

Minor:

Major:

Minor:

4. There are several steps I can take to be successful in college.

Major:

Minor:

Major:

Minor:

Reading-Writing Connection: Supporting Details

Exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Return to the Thesis exercise you did previously. As part of that exercise, you identified two topic sentences from your selected reading. Now, look more closely at the paragraphs where those two topic sentences came from.

- Write a paragraph that identifies the type of support that each paragraph from the reading uses to reinforce each of those two topic sentences. Are they narrative or personal examples? Are they facts or statistics? Are they quotes or paraphrases from research materials?

- Write another paragraph that compares the effectiveness of the supporting claims of one of the selected paragraphs against the other one. Which seems more successful in its goal? Why do you feel that way?

Contributors

- Adapted from English 9Y Pre-College English. Provided by: Open Course Library. CC BY 3.0

- Adapted from Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences. Provided by: Lumen Learning. CC-BY-NC-SA

- Adapted from Methods of Discovery: A Guide to Research Writing. Authored by: Pavel Zemliansky. Provided by: Libretexts. CC BY: Attribution

This page last updated June 6, 2020.