6.1: Identifying key concepts and alternative terms to type in

- Page ID

- 65090

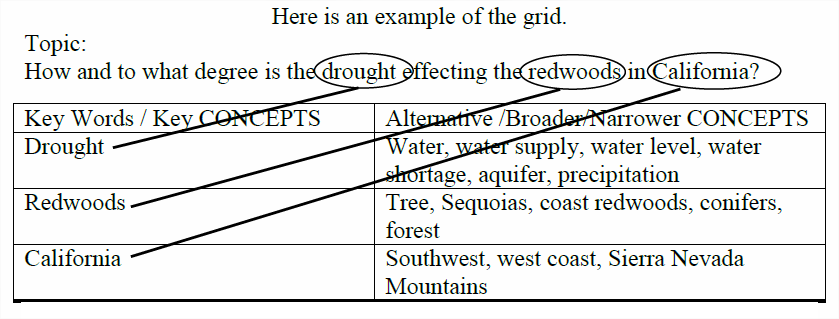

Let’s say that, after doing the work of choosing a topic as described in section 5 above, you have come up with the topic sentence:

How and to what degree is the drought effecting the redwoods in California?

Type your topic sentence or research question. Identify the key words or concepts in your topic sentence by bolding or underlining them. In the example above, the following words would be underlined: drought, redwoods, California. If you identify words such as impact, compared to, related to, benefits of, be sure and come up with good alternative words for them because words like impact, compared… are rarely good choices to use in a computer search. Identifying alternative terms for such words is discussed later. It is often best just to avoid using such words as your key words altogether. Write alternative words for all your key concepts.

In addition to synonyms, you are looking for related terms: broader terms, narrower terms and antonyms (opposites). Your topic, no matter what it is, is on a continuum from narrow to broad in a continuum of topics. You want to create a continuum for your topic for two good reasons into which we will delve after this example.

Let’s say you are going to do a paper/project on the environment. It seems obvious that is far too broad a topic. So, we narrow it down. How about the environment of animals (still too broad)? Let’s whittle this all the way down: the environment of birds, the environment effecting the reproduction of birds, the environment effecting reproduction in birds of the Americas, the environmental pollution effecting reproduction in birds of the eastern Pacific, the environmental pollutions effecting the eggs of birds of the eastern Pacific, the effects of pesticides on the eggs of birds of the eastern Pacific in 1940-70, the effect of DDT on the eggs of birds of the eastern Pacific in 1940-70s, the effect of DDT use in the 1940-70 on the eggs of the pelicans on the Coronado Islands.

The example above is most certainly not the only way one could narrow down this topic, but you do want to take your topic and create your own continuum from broad to narrow. We started with the huge topic, environment. If you started with the topic of the effect of pesticides on birds, you would want to create a continuum that got gradually broader all the way up to environment and gradually got more detailed all the way to effect of DDT use in the 1940-70 on the eggs of the pelicans on the Coronado Islands as an example. Again, there is not just one way to create a continuum. The important thing is to create one. This makes it clear to you what exactly you are interested in learning about. If, for example, the continuum above is what you developed and you found a great article you really found interesting about pesticides and dolphin reproduction in the eastern pacific, you would know you have strayed off your topic and need to refocus on the search results that fall on your continuum and answer your research question.

There are two more important reasons to think through a continuum. Let’s suppose you are interested on the impact of pesticides on birds as your paper/project topic.

- Rarely do you find books or articles exactly on your topic. Most often, the information resources you use will be broader and narrower than your topic. A subject specific encyclopedia on how pesticides harm wild life is an example of a source broader than your topic. In it you may find a chapter on birds. Additionally, you might discover in your reading that pelicans were put at extreme risk because of the heavy use of DDT (a pesticide heavily used in the 1940s and 50s). That is much narrower than your topic, but you certainly could use an article or two about this to make a point.

- Because the resources you use will be broader and narrower than your topic, the words you use in your searches to find those resources will also need to be broader and narrower than your topic to find them. To find that encyclopedia on how pesticides harm wildlife, for example, you would use broader terms than you find in your topic sentence. For example, you might use the words animals and pesticides and not use the word birds to find it. To find a supporting article, you may try some narrower terms than those in your topic sentence. For example, DDT and pelicans.

Now that you have several questions about your topic and you know where your topic falls on a continuum of topics (you have done that, right! Don’t skip a step!) You want to make a grid. This grid will consist of key words and concepts for your topic and alternative terms for those. Include broader and narrower terms as well as synonyms and antonyms because the authors will often use different words for your topic than you have used. You will miss good information if you only use words from your topic sentence. This is one of many reasons you will be doing several searches to get the best information. Some words will work well in one database while different words will work well in another. You will find it useful to do multiple searches in the same database using different words. In our example, we might type in pesticide and birds, words right out of the topic sentence, and get some good results. We would, however, miss articles in which the author used the terms insecticides and birds. It is important, therefore, to try many combinations of terms to find all the relevant information resources (e.g. books and articles).

Pay close attention to making an accurate grid because, when done right, you will be able to use it to create a search strategy. Doing this now will save you time later. You will have far less off-topic resources to sift through. Make a grid with the key concepts down the left hand side of your page. They should be the exact words from your topic. List to their right the broader terms, narrower terms, synonyms and antonyms.

Be sure that you only use concepts that reflect key concepts. If you have a word you really want to use that is not in your topic, perhaps your topic sentence or research question need to be rewritten to include this word(s) or the concepts it represents. If that word or concept is of interest to you and the due date for your paper/project still allows you time to begin again, a change of topic may be in order.

Notice the grid asks for key concepts and not key words. Sometimes your concepts will be expressed in more than one word, for example, Sierra Nevada Mountains. You want to preserve the concept, not the individual words. Another example would be if your paper/project had something to do with storm drains, you would want to keep those two words together since you do not want information on winter storms or the drains in your house. Why this is important will become very clear in a bit. (You will add more and more alternative words to the grid as your research progresses. See 6E for details.)

Notice the word effecting was not used as a key concept. That is because it is best not to use words effecting, influence, impact and so on in your first searches. Try to use only solid nouns. As with most things in this text, there are exceptions. If you already have a little knowledge about your topic and you have a few effects, influences or impacts you want to explore, add a grid line for the terms. For example:

- Key Words / Key Concept*: Alternative/Broader /Narrower Concepts

- Effecting: Sap, sap depletion, pests, beetles

Go ahead and use words like effecting, influence and impact if you have exhausted your other terms and other search strategies soon to be explained or if you are getting far too many hits. *Do not confuse the terms “key words” or “key concepts” in the grid with “keywords” you sometimes see in a database. “Key words/key concepts” heremeans the main ideas within your topic. “Keywords” as used in databases will be discussed later (See 6E).

Truncation and Wildcards

Truncation and wildcards come in handy when the words you want to search have slight variations. Perhaps just one letter could broaden your search. For example: perhaps you want to find both the singular and the plural of a word: turtle and turtles, woman and women. Or perhaps you want to find both the American English word color and the British English word colour. This can be done using truncation and wildcards which saves you an additional search and ensures you capture all relevant results. Some help screens for some databases will call truncation a type of wildcard. Check the database help screens to determine what symbols to use for truncation and wildcards and what happens when you use them. Each database is different. While truncation, as described below is generally standard, wildcard searching varies greatly from database to database. A common usage follows the truncation description below.

Truncation

To truncate means to cut off. In most databases, by adding a symbol to a word that you cut off will garner results that have all the permutations of that word the database knows that begin with the letters you typed in. For example, pira* will find pirate, pirates, piracy. But this is a bad example, because it will also find the word piranha and piranhas and so on. So it is very important that you cut off your words where it makes sense or you could end up with piranhas or worse. It is an easy way to search the singular and plural of a word at the same time. If all you are interested in is a pirate or two, search the term pirate*.

The asterisk (* shift 8 on your keyboard * ) is the most often used symbol, but you might find the rare database that uses other symbols for truncation such as a dollar sign or a question mark. Even rarer databases allow for left hand truncation meaning you can ask the database to find variant beginnings of words instead of endings.

Wildcards

Using wildcards is a way of replacing one letter within a word or at the end of a word. When wanting to get both the singular and the plural of a words such as women and woman, the last vowel can be replaced with a wildcard symbol: wom?n. Both words would then be searched. Using a wildcard is also useful when searching for words that are spelled differently in British English. For example, color is spelled colour. Not all databases allow this and the symbol for this may also vary. The most commonly used symbols are a number sign (#) or a question mark (?). So if you want to include resources that may have been written by our cousins across the pond, you may choose to type colo#r. That would retrieve items with both color and colour in them because the # replaces one letter or is ignored by the search. What would you expect wom?n to find?

The bottom line to know about truncation and wildcards is that they exist, that they are defined and used differently from database to database and that they can expand your results. Check the databases’ help screens and experiment to see just what results you get.