4.2: “Everyday” Arguments

- Page ID

- 35915

Now we will discuss some other common arguments that you might often hear or read about that are also poor, but often not because they are question-begging. We’ll begin with some arguments against abortion.

“Against” Abortion

4.2.1.1 “Abortion ends a life.”

People often ask, “When does life begin?” Some people wonder if fetuses are “alive,” or when they become “life.” Some argue that abortion is wrong because “life begins at conception,” whereas some who support abortion sometimes respond that “fetuses aren’t even alive.” There are a lot of debates here, and to get past them, we need to ask what is meant by calling something alive, living or a life.

This is often considered a “deep” question, but it’s not. Consider this: are eggs (in women) alive? Are sperm cells alive? Yes to both—they are biologically alive—and so when a sperm fertilizes an egg, what results is a biologically living thing. Above, we defined abortion as a type of killing and, of course, you can only kill living things. So, yes, fetuses are alive, biologically alive, from conception: they are engaged in the types of life processes reviewed on page 1 of any biology textbook.

Some people think that fetuses being alive makes abortion is wrong, and so they enthusiastically argue that fetuses are biologically alive. And some who think that abortion is not wrong respond by arguing that fetuses are not even alive. These responses suggest concern with an argument like this:

Fetuses are biologically alive.

All things that are biologically alive are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill.

The first premise is clearly true: anyone who would deny this knows very little about basic biology, or just misunderstands what’s being said.

The second premise, however, is obviously false and uncontroversial examples show that. Mold, bacteria, mosquitos and plants are all biologically alive, but they aren’t wrong to kill at all. So, just as acknowledging that abortion involves killing doesn’t mean that abortion is wrong, recognizing that biological life begins at conception doesn’t make abortion is wrong either.

Now, perhaps people really mean something like “morally significant life” or “life with rights,” but that’s not what they say. If that’s what people mean, they should say that, since being clear and accurate is important for thinking about debated issues.

4.2.1.2 “Abortion kills babies and children.”

Classifying fetuses as babies or children obscures any potentially-relevant differences between, say, a 6-week old fetus and a 6-day old baby or 6-year old child. This claim assumes that fetuses—at any stage of development—and babies are the same sort of entity and so have similar rights. So the claim is question-begging, as was discussed above in the section on definitions, and uses loaded emotional language: it doesn’t make for a good argument against abortion.

4.2.1.3 “Abortion is murder.”

Murder is a term for a specific kind of killing. As a moral term, it refers to wrongful killing. As a legal term, it refers to intentional killing that is both unlawful and malicious. Since abortion is legal in the US, most abortions cannot be legally classified as murder because they are not illegal or unlawful. Moreover, abortions don’t seem to be done with malicious intent. When people claim that abortion is murder, what they seem to mean is either that abortion should be re-classified as murder or that abortion is wrong, or both. Either way, arguments are needed to support that, not question-begging slogans.

4.2.1.4 “Abortion kills innocent beings.”

Fetuses are often described as “innocent,” meaning that they have done nothing wrong to deserve being killed or that would justify killing them. Since killing anyone innocent is wrong, this suggests that abortion is wrong.

“Innocence,” however, seems to be a concept that only applies to beings that can do wrong and choose not to. Since fetuses can’t do anything—they especially cannot do anything wrong that would make them “guilty” or deserving of anything bad—the concept of innocence does not seem to apply to them. So saying that banning abortion would “protect the innocent” is inaccurate since abortion doesn’t kill “innocent” beings: the concept of innocence just doesn’t apply: fetuses are neither innocent nor not innocent.

4.2.1.5 “Abortion hurts women.”

Some claim that abortions are medically dangerous. This is generally not true, if you look at the medical research: abortions are less dangerous than pregnancy and childbirth, which many women die from, even today. But for this argument to succeed, we’d also have to believe this:

All dangerous activities are morally wrong or should be illegal.

Even if this idea is restricted to medically dangerous activities, this principle is just not true: people are and should be free to choose to accept risks; we all do it every day. So this argument is unsound, even if it overestimates the risks of abortions.

Another concern is that abortions are psychologically or emotionally dangerous. When this is the concern, it is sometimes expressed this way: “Many women regret their abortions.” When women regret abortions (some women do; some women don’t), this is sometimes because they believe they have done something wrong and so the argument—which was discussed above—is question-begging since it assumes that abortion is wrong. But, again, not everything that’s emotionally harmful is wrong or should be illegal: not having children sometimes leads to major regret and depression for some people, but surely not having children shouldn’t be criminalized because of it.

Finally, it’s fair to observe that it is disingenuous to have major concerns about this narrow area of women’s health but be indifferent to or hostile towards other practices and policies that would benefit women’s health in other ways. This is especially disingenuous when this abortion-related health concern is expressed for women who are racial minorities, who already often have increased health inequalities, including many related to pregnancy and childbirth.6

4.2.1.6 “The Bible says abortion is wrong.”

People often appeal to religion to justify their moral views. Some say that God thinks abortion is wrong, but it’s a fair question how they might know this, especially since others claim to know that God doesn’t think that. Some say that “only God should decide who exists and who ceases to exist, who is born and who dies,” yet this phrase lacks meaning and it fails to provide moral guidance. For example, people frequently try to reproduce, which causes people to come into existence, and this is rarely considered immoral. At the other end of the life spectrum, a "hands off" approach to end of life decisions is not just irresponsible, it is sometimes profoundly immoral.

In reply, it is sometimes said that the Bible says abortion is wrong (and that’s how we know what God thinks). But the Bible doesn’t say that abortion is wrong: it doesn’t discuss abortion at all. There is a commandment against killing, but, as our discussion above makes clear, this requires interpretation about what and who is wrong to kill: presumably, the Bible doesn’t mean that killing mold or bacteria or plants is wrong. And there are verses (Exodus 21:22-24) that, on some interpretations, suggest that fetuses lack the value of born persons, since penalties for damage to each differ. This coincides with common Jewish views on the issue, that the needs and rights of the mother outweigh any the fetus might have.

However any verses are best interpreted, they still don’t show that abortion is wrong. This is because the Bible is not always a reliable guide to morality, since there are troubling verses that seem to require killing people for trivial “crimes,” allow enslaving people (and beating them), require obeying all government officials and more. And Jesus commanded loving your neighbor as yourself, loving your enemies and taking care of orphans, immigrants and refugees, and offered many other moral guidelines that many people regard as false.7 Simple moral arguments from the Bible assume that if the Bible says an action is wrong, then it really is wrong (and if the Bible says something’s not wrong, it’s not wrong), and both premises don’t seem to be literally true, or even believed.

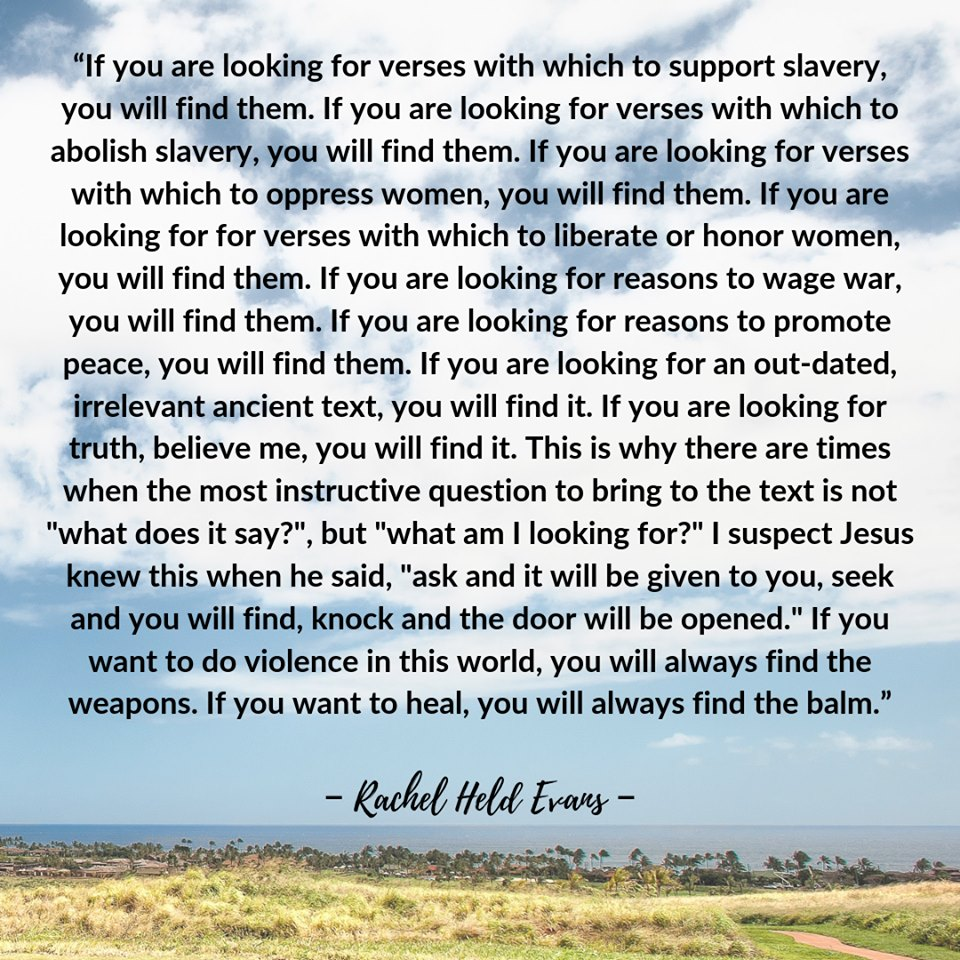

This all suggests that people sometimes appeal to the Bible, and other religious sources, in selective and self-serving ways: they come to the Bible with their previously-held moral assumptions and seek to find something in the Bible to justify them. A quote from the late Christian author Rachel Held Evans gives insight and wisdom here:

There is an interesting and important Biblical connection here worth mentioning though. Some argue that if women who want abortions are prevented from having them, that forces them to remain pregnant and give birth and this is like forcing women to be like the “Good Samaritan” from the New Testament who went out of his way, at expense to himself, to help a stranger in great need (Luke 10:25-37). (The analogy is imperfect, as analogies always are, yet imperfect analogies can yield insight.)

The problem is that in no other area of life is anyone forced to be a Good Samaritan like a pregnant woman would: e.g., you can’t be forced to donate an organ to anyone in need (even to your child or parent8); you can’t even be forced to donate your organs after you are dead! Nobody other than pregnant women would be forced by the government—under threat of imprisonment or worse—to use their body to help sustain someone else’s life. (Any “Good Samaritan” laws demand far, far less than what pregnancy and childbirth demand.) So it is unfair to require women to be Good Samaritans but allow the rest of us to be like the priest and Levite in the story who go out of their way to help nobody.

Finally, it’s important to remember that laws should not be based on any particular religion. If you are not, say, a Hindu, or a Buddhist, or a Rastafarian, you probably don’t want laws based solely on one of those religion’s values. Laws should be religiously-neutral; on that we all should agree.

4.2.1.7 “Abortion stops a beating heart.”

This claim, if given as an argument, assumes that stopping a beating heart is wrong. The assumption, however, is just obviously untrue: e.g., during open heart surgery, surgeons temporarily stop the patient’s heart so that repair can be made to the still heart: they would permanently stop that heart if they replaced it with an artificial heart. If there were somehow an independently beating heart, attached to nobody, that heart wouldn’t be wrong to stop. Whether a heart is wrong to stop or not depends on who is around that heart and their value or rights, not anything about that heart by itself. Finally, embryos and early fetuses do not even have hearts, as critics of recent “heartbeat” bills have observed! (The heart fully develops much later in pregnancy.)

If, however, this widely expressed concern about a heartbeat isn’t meant to be taken literally, but is merely a metaphor or an emotional appeal, we submit that these are inappropriate for serious issues like this one.

4.2.1.8 “How would you like it if ...?”

Some ask, “How would you like it if your mother had had an abortion?” Others tell stories of how their mother almost had an abortion and how they are grateful she didn’t. Questions and stories like these can have emotional impact, and they sometimes persuade, but they shouldn’t. Consider some other questions:

● How would you like it if your mother had been a nun, or celibate, all her life? ● How would you like it if your mother had moved away from the city where she met your father, and they never met? ● How would you like it if your father had decided early in life to have a vasectomy?All sorts of actions could have prevented each of our existences—if your parents had acted differently in many ways (perhaps almost any ways), you wouldn’t be here to entertain the question: at best, someone else would be9—but these actions aren’t wrong.

Some might reply that if you had been murdered as a baby, you wouldn’t be here to discuss it. True, but that baby was conscious, had feelings, and had a perspective on the world that ended in being murdered: an early fetus is not like that. We can empathetically imagine what it might have been like for that murdered child; we can’t do that with a never-been-conscious fetus, since there’s no perspective to imagine.

In sum, these are some common arguments given against abortion. They aren’t good. Everyone can do better.

“For” Abortion

Many common arguments “for” abortion are also weak. This is often because these arguments simply don’t engage the concerns of people who think abortion is wrong. Consider these often-heard claims:

4.2.2.1 “Women have a right to do whatever they want with their bodies.”

Autonomy, the ability to make decisions about matters that profoundly affect your own life, is very important: it’s a core concern in medical ethics. But autonomy has limits: your autonomy doesn’t, say, justify using your body to murder an innocent person, which is what some claim abortion is. The slogan that “women can do what they want with their bodies” does not engage that claim or any arguments given in its favor. As an argument, it’s inadequate.

4.2.2.2 “People who oppose abortion are just trying to control women.”

They might be trying to do this. But they might be trying to ban abortion because they believe that abortion is wrong and should be illegal. (Again, critics of abortion might respond that abortion advocates just want to “engage in immorality without consequences!” Is that true? No, pro-choice advocates argue).

Speculations about motives don’t engage or critique any arguments anyone might give for their views, and so are unwise and fruitless. (If you doubt that thinking critically about arguments and evidence here would do any good, do they have any better ideas that might do more good?)

4.2.2.3 “Men shouldn’t make decisions about matters affecting women.”

Insofar as women profoundly disagree on these issues, some women must be making, or urging, bad decisions about matters affecting women: all women can’t be correct on the issues. And some men can understand that some arguments (endorsed sometimes by both women and men) are bad arguments. And men can give good arguments on the issues.

In general, someone’s sex or gender has little to no bearing on whether they can make good arguments about matters that affect them or anyone else. Furthermore, the existence of transgender men who have given birth further undermines the thought that one sex or gender is apt to have more correct views here.

Finally, discouraging any competent people from engaging in reasoned discussion and advocacy is simply unwise: that is not part of a smart and effective strategy for social change.

4.2.2.4 “Women and girls will die if abortion isn’t allowed.”

Historically, this has been true, and is likely to remain the case. However, this fact is apt to not be persuasive to some people who believe that abortion is wrong: they will respond, “If someone dies because they are doing something wrong like having an abortion, that’s ‘on them,’ not those who are trying to prevent that wrong.” Observing that women will die if abortions are outlawed doesn’t engage any arguments that abortion is wrong or give much of a reason to think that abortion is not wrong. Again, this type of engagement is necessary for progress on these issues.

In sum, while we argue below that people who believe that abortion is generally not morally wrong and should be legal are correct, they sometimes don’t offer very good reasons to think this. We aim to provide these reasons below.