10.6: Protest Songs

- Page ID

- 90744

Florence Reece, “Which Side Are You On?”

Our first example was certainly intended as a protest—and a pointed, personal protest at that. The creator of this song was not a popular performing artist but an impoverished union organizer in rural Kentucky, unknown outside of her own community until long after the song was written. She did not have commercial success on her mind but, rather, the immediate survival of her family, which had been targeted for destruction by a powerful oppressive force.

Florence Reece (1900-1986) was the daughter and wife of coal miners. Born in Tennessee, she married Sam Reece at the age of sixteen and moved with him to Harlan County, Kentucky. It was here that a bloody conflict between mine workers and owners, now known as the Harlan County War, would play out between 1931 and 1939. In addition to fighting to protect her family, Florence documented the period in poems and songs that both reflected her desperate situation and called on fellow members of the mining community to maintain the struggle.

During World War I, the coal mining industry enjoyed a boom in production. Coal, after all, was needed for the production of steel, of which the war effort required an endless supply. Although coal companies saw the greatest profits, in- dividual coal miners also lived comfort- ably during this period: Because there was enormous demand for their labor, the United Mine Workers (UMW)—the union that represented coal miners—was able to secure high wages on their behalf. Following Armistice, however, coal companies failed to scale back their pro- duction, with the result that the market was overwhelmed and prices dropped precipitously. Many coal miners were fired, while those who remained on the job saw their wages cut again and again. Then, in 1929, the Great Depression hit, and conditions for mine workers became even worse. The UMW found that it had lost its bargaining power and withdrew, leaving workers without advocacy.

Miners who lost their jobs or found the conditions intolerable could not sim- ply leave. To begin with, work was scarce in the early 1930s. It was the structure of the mining industry, however, that posed the greatest challenges. Miners lived in company towns that were owned and operated by the mining conglomerates. They could not buy their own homes and were reliant on the company store for household goods and groceries—stores that often inflated prices and encouraged mine employees to go into debt. Miners who wanted to leave often were not able to do so, since they owed money to their employer, while those who lost their jobs simultaneously became homeless.

Another union stepped in to fight on behalf of the desperate miners, whose labor was still necessary to keep the in- dustry going. That union, the National Miners Union, was backed by the American Communist Party, and it was willing to undertake extreme actions. The mine owners, on the other hand, were able to buy the support of local sheriffs, the state militia, and the court system. They even hired Chicago gangsters to take out union leaders. The ensuing conflict resulted in countless deaths on both sides, including hundreds of children and in- fants who starved to death or were denied medical services by the company doctors. One particular skirmish prompted Florence Reese to create “Which Side Are You On?”11 Sam Reece was a union leader and, therefore, a target for the company- backed law enforcement. One day, Sheriff J.H. Blair arrived at the Reece home with his men. They ransacked the house in front of Florence and her seven terrified children and then settled in to wait for Sam, with the intention of shooting him dead when he arrived. Sam, however, had been warned about the raid and did not return home that day. After the men left at nightfall, Florence tore a calendar off the wall and wrote the text to her song on the back.

|

“Which Side Are You On?”11. Composer: Florence Reece Performance: Florence Reece |

This rendition of “Jack Went A-Sailing” was recorded in 1968.

Florence Reece was a lyricist, not a composer, and when she wrote songs, she sang the words to familiar pre-existing melodies. For “Which Side Are You On?” she chose the melody of an old Baptist hymn, which she knew as “Lay the Lily Low.” The same melody is also used for the traditional ballad known variously as “Jack Munro,” “Jack Went A-Sailing,”12 and “The Maid of Chatham.” The ballad is probably of British origin and, therefore, can be considered a likely source for the hymn melody known to Reece.

The hymn melody was a natural and effective choice. As a committed Christian, Reece would have been likely to select tunes that she had learned in the context of worship. This particular tune is simple and easy to sing. It is also a bit ominous, given its minor mode and descending melody—the last note of each phrase is the lowest. As a result, the tune cannily captures the spirit of Reece’s message

Reece’s message is straightforward and unadorned. She does not rely on poetic imagery or metaphor—and she doesn’t need to. In the first stanza, she praises the union. In the second, she announces that victory is assured. In the third, she makes it clear that everyone involved in the conflict must choose a side, calling out the sheriff who threatened her family by name. In the fourth, she brings in her concern about the children of miners. In the fifth, she exhorts miners to be honest and brave. In the sixth, she proclaims her mining heritage—and incorporates her only flight of poetic fancy, referring movingly to her deceased father as “in the air and sun.” And in the seventh (not heard in our recording), she returns to the theme of collective strength through unionization. The chorus—a simple question, repeated four times—drives home the message without any ambiguity.

Reece did not record her song until much later in life. When she did so, she sang in the simple, unadorned style of many Appalachian ballad singers. She sings without accompaniment, just as she would have in 1931. Her words have a force that comes not only from her personal experiences but from her knowledge that they continue to be relevant. Although the Harlan County miners emerged victorious in 1939, another conflict would take place in 1973, when 180 miners employed by the Eastover Coal Company’s Brookside Mine and Prep Plant went on strike for improved working conditions and decent wages. Reece joined the strikers in solidarity, and her rendition of “Which Side Are You On?” before a crowd of miners and their families was recorded in the documentary Harlan County, USA.

Reece’s song first gained mainstream popularity when it was recorded in 1941 by the Almanac Singers,13 a folk revival group based in New York City and led by a young Pete Seeger. The Almanac Singers were actively engaged with left-wing politics, and they were interested in supporting the labor movement. Their version employs guitar and banjo accompaniment and features a large group of singers on the chorus—a sonic representation of the collective workers represented by the union. The song was later recorded by dozens of other artists, and it has been used in protests around the world.

|

“Which Side Are You On?” 13. Composer: Florence Reece. Performance: The Almanac Singers (1955) |

Bob Dylan, “Blowin’ in the Wind”

It is not surprising that a folk revival group like the Almanac Singers would record Reece’s protest song. Participants in the folk revival movement were almost universally preoccupied with social justice issues, and its singers would both record and create countless protest anthems. In fact, it is difficult to select a representative example. Bob Dylan’s classic “Blowin’ in the Wind,”14 however, will serve our purpose well. It will allow us to consider the connection between style and message, to examine the typical characteristics of a successful protest song, and to consider the ways in which a protest song can mean something to listeners (and singers) that was never intended by its creator.

|

“Blowin’ in the Wind” 14. Composer: Bob Dylan Performance: Bob Dylan (1963) |

The folk revival movement began in the 1930s, when young people in northern cities began to take an interest in the songs and tunes of rural Southern musicians. The movement was largely driven by field collectors, the most prominent of whom were the father-son team of John and Alan Lomax. Collectors would travel through rural communities recording folk artists. In fact, it was Alan Lomax who collected “Which Side Are You On?” from Florence Reece in 1937. Sometimes, collectors would actually bring rural performers up north to perform on college campuses and at folk festivals. For the most part, however, the folk revival was driven by northern musicians performing the songs they learned from field recordings, using the same acoustic instruments—especially guitar—that were common in the south.

Although the folk revival was sparked during the Great Depression, it did not exert mainstream influence until the 1960s, when the counterculture movement adopted folk music as a favored means of expression. The 1960s saw extraordinary social upheaval, as young people rebelled against the conservative social values of the post-WWII era, marginalized groups fought for civil rights, and anti-war activists protested US involvement in Vietnam. Folk music quickly became an important vehicle for political speech.

Most of the central figures in the folk revival did not become famous performing authentic folk music. Instead, they wrote and recorded original songs in a folk style. Perhaps the most influential and respected of these artists was Bob Dylan, who produced an extraordinary catalog of songs featuring his own evocative poetry.

Dylan was regarded as a folk singer because he accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica, but he was more interested in expressing himself creatively than in preserving music of the past.

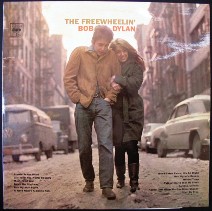

Bob Dylan was born Robert Allen Zimmerman to Midwestern Jewish parents in 1941. He moved to New York City in 1961, where he legally changed his name while still using a variety of pseudonyms to record and publish his creative work. Dylan’s eponymous first album, released in 1962 by Columbia Records, consisted mostly of familiar folk and gospel songs. It was hardly a success, barely breaking even in financial terms, and skeptics within Columbia recommended that his contract be terminated. Dylan’s producer stood by him, however, and his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), was considerably more successful. The album’s songs were decidedly topical, addressing political concerns ranging from integration to the Cuban missile crisis. The first song on the album was “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

“Blowin’ in the Wind” is in three stanzas, each of which concludes with a refrain. Each of the stanzas consists of a series of three questions, the answer to which is promised by the refrain, even though it is never in fact provided. Within each stanza, the questions become increasingly pointed and specific. The first in each set tends to be vague: It does not connect with a social issue and cannot be ascribed specific meaning. The later questions, however, begin to make explicit reference to ongoing political crises. Mentions of “cannon balls” and “deaths” clearly conjure the image of war, while the lament that some people are still not “allowed to be free” elicits scenes of oppression at home and abroad.

However, despite the growing specificity and attendant urgency of the questions, Dylan never makes the subject of his song exactly clear. He is concerned about war, but which war? He laments oppression, but whose? We can easily guess what was on his mind in 1962, when he wrote this song. The Vietnam War, which had been ongoing since 1955, was beginning to attract significant opposition in the United States, while the civil rights movement was quickly gaining momentum. Dylan became particularly involved in the struggle for racial equality. He performed at the 1963 March on Washington, and his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’ (1963), contained a number of songs that addressed the struggles and victories of equal rights campaigners.

We might, therefore, imagine that we know what this song meant to Dylan, but that does not mean that the significance of “Blowin’ in the Wind” is limited to the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. Dylan himself ensured that his song could speak to political issues beyond his own time and place. He did so by refraining from mentioning the social causes of his day and instead speaking in broad, almost universal terms. His concerns about war and freedom apply just as well to ancient struggles as they do to those that have yet to take place. We might draw a contrast here with Reece’s song, which explicitly mentions mining and even names one of her adversaries.

Dylan’s music suits his message: Each of the questions begins with the same melodic phrase and ends on an inconclusive pitch, indicating that there is more to be said, while his refrain, which promises an answer, ends on the home pitch (the tonic scale degree). The melody is highly repetitive, making it easy to learn. It also encompasses only a small vocal range and moves almost entirely by step (conjunct motion), making it easy to sing. Finally, the simple guitar accompaniment can be replicated by a moderately competent player. In short, this song, which requires neither special equipment nor advanced musical training, can be performed by almost anyone.

In this recording, we hear Odetta sing the spiritual “No More Auction Block.”

However, Dylan’s melody also carries meaning on a deeper level. Like Reece, he did not write his melody from scratch, but rather adapted it from another song. His source, the African American spiritual “No More Auction Block,”15 provides us with additional insight into what the song might mean, for “No More Auction Block” describes the relief of a formerly-enslaved person who has escaped from slavery and is no longer to be subjected to humiliations and abuses. According to Alan Lomax, the song originated in Canada, where it was sung by former slaves after the practice was abolished there. It later spread to the United States. Dylan’s melody is not identical, but one can easily hear that he borrowed the opening melodic phrase. When we listen through the lens of the spiritual, we can feel even more confident about the relationship between “Blowin’ in the Wind” and the civil rights movement.

But we can’t go too far in ascribing specific meaning to “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan himself refused to explain what the song meant, or even to admit that it meant anything in particular. When the song was published in Sing Out! magazine in 1962, it was accompanied by the following note from Dylan:

There ain’t too much I can say about this song except that the answer is blowing in the wind. It ain’t in no book or movie or TV show or discussion group. Man, it’s in the wind — and it’s blowing in the wind. Too many of these hip people are telling me where the answer is but oh I won’t believe that. I still say it’s in the wind and just like a restless piece of paper it’s got to come down some ... But the only trouble is that no one picks up the answer when it comes down so not too many people get to see and know ... and then it flies away. I still say that some of the biggest criminals are those that turn their heads away when they see wrong and know it’s wrong.

In other words, “Blowin’ in the Wind” is about searching for answers, not providing them.

Dylan went even further in distancing his song from the political turmoil of the early 1960s, stating clearly before its first ever performance, “This here ain’t no protest song or anything like that, ‘cause I don’t write no protest songs.” It’s easy to understand why Dylan, an artist with a wide-ranging creative vision, would not want to be pigeonholed as a writer of protest songs. All the same, his claim rings hollow, especially in light of the many activists who were inspired by his song and the social movements that have adopted it.

We will examine two recordings of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” both made in 1963. First, we will listen to Bob Dylan’s own version, which was released as a single and included as the lead track on his second album. This version was moderately successful: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan peaked at 22 on the Billboard album charts. However, Dylan’s songs have almost always done better when sung by other performers. We will also listen to the version by the folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary, who can be considered responsible for making “Blowin’ in the Wind” a hit. Their recording reached number 2 on the Billboard singles charts.

Dylan’s version is remarkably simple and unpolished. He plays a regular rhythm on the guitar, choosing the most obvious chords (he uses only three). At the end of each verse, he pauses to blow a few notes on the harmonica. His timing as a singer was always idiosyncratic, and sometimes the words don’t fall on the beat, as you would expect. His voice is rough, and he doesn’t seem to put any effort into expressing the meaning of the text.

The version recorded by Peter, Paul & Mary is considerably more sophisticated.16 Although the group also accompanies their singing with guitars, they use two instruments, not one, and the guitars are played using a refined finger-picking style that is far removed from Dylan’s simple strumming. We hear the guitars right at the beginning, when they provide an extended introduction to the song. Peter, Paul & Mary also chose more nuanced and compelling harmonies than Dylan had. As a result, their version is significantly more difficult for an amateur to replicate.

|

“Blowin’ in the Wind” 16. Composer: Bob Dylan. Performance: Peter, Paul & Mary (1963) |

All three members of the group were singers, and they used this to their advantage by varying the vocal texture phrase by phrase. The first verse begins in two-part harmony with Mary Travers on the melody, but grows in volume and energy when a third voice enters to underscore the final question. Then the men sing the first refrain without Mary, who subsequently sings the first question in the second verse alone. All three take the second question in unison and the third in harmony before Mary sings the second refrain as a solo. The third verse builds to a climax as Mary moves from the melody to a high harmony, after which she sings the final refrain alone. All three provide a final unison refrain to close out the recording. The changes in texture draw the listener’s attention to some of the more important questions (the one about freedom is especially forceful), while also making the song more interesting.

Finally, Peter, Paul & Mary’s version has a polish that is lacking in Dylan’s. The rhythms are regular and predictable, while the voices of the singers are carefully controlled and perfectly in tune. This is not to say that Peter, Paul & Mary’s version is better, and many people prefer Dylan’s recording for its simplicity and honesty. However, this comparison gives us some insight into what makes a hit: It is not only the song that matters, but the arrangement and performance.

Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, “Get Up, Stand Up”

In our previous example, style played an important role in the construction of a successful protest song. On the one hand, the acoustic instruments and simplified techniques of the folk revival made “Blowin’ in the Wind” easy to perform—and also appropriate for informal outdoor renditions in the context of rallies, marches, or picket lines. On the other, the folk style positioned “Blowin’ in the Wind” in a long line of protest songs, of which “Which Side Are You On?” is an early example. In other words, it is typical for a folk song to also be a protest song, and listeners therefore have an easy time accepting “Blowin’ in the Wind” in this role.

Style will also be important to our next example. Some characteristics of the reggae style, which relies on a range of amplified electric instruments, make “Get Up, Stand Up” (1973) somewhat more difficult to use in the context of an on- the-ground protest. At the same time, reggae itself is deeply connected with social rebellion and resistance to oppressive ruling powers—so much so that the genre itself might be considered a protest. In the case of this song, therefore, a knowledge of the reggae style and its historical context is vital to understanding the message of the music.

|

“Get Up, Stand Up” 17. Composer: Bob Marley and Peter Tosh Performance: Bob Marley and the Wailers (1973) |

Reggae has been around since 1968, when it emerged as the most widely- performed and influential style of popular music in Jamaica. Reggae represented a synthesis of various music traditions of Central and North America. Jamaican listeners had easy access to American popular music, which was imported on recorded discs and broadcast on the radio, and they were particularly enthusiastic about rhythm ‘n’ blues and jazz. Following Jamaican independence in 1962, however, Jamaicans were increasingly interested in developing unique popular music styles that represented their national identity. The first of these were ska (an uptempo style featuring jazz instrumentation and off-beat accents) and rocksteady (a slower version of ska), both of which influenced reggae. Ska and rocksteady also drew from the Caribbean traditions of mento and calypso—as did reggae in its own turn.

The meaning of the Jamaican English term “reggae” has been much debated. It can be used to refer to a person who is poorly dressed, or to a quarrel. It has also been connected with the term “streggae,” which can describe a loose woman. The term was first used in a musical context in the Maytals’s 1968 song “Do the Reggay,” which also established the stylistic conventions of what would become a major new genre. The lead singer of the group, Frederick “Toots” Hibbert, provided his own definition of the term: “Reggae just mean comin’ from the people, an everyday thing, like from the ghetto. When you say reggae you mean regular, majority. And when you say reggae it means poverty, suffering, Rastafari, everything in the ghetto. It’s music from the rebels, people who don’t have what they want.” Reggae music, therefore, would speak to regular Jamaicans, and it would address their rebellious desire to overthrow the forces that kept them in poverty.

Hibbert also mentions Rastafarianism, which is another vital ingredient to reggae. We can understand neither the reggae worldview nor the specific lyrics of reggae songs without addressing this movement. Rastafarianism can trace its roots to the “Back to Africa” movement of the 1920s. The leader of the movement was Marcus Garvey, a firey political orator of Jamaican origin who advocated for pan- African unity. In his view, those of African descent in all parts of the world should take pride in their heritage and throw off the yoke of white colonial oppression. He sought independence for black majority colonial states but also encouraged members of the African diaspora to return to Africa, where he imagined the founding of a single unified African state with himself at the head. While organizing in the United States, Garvey went so far as to establish a shipping company, the Black Star Line, for the express purpose of returning African Americans to the African continent. This project, however, led to Garvey’s 1923 conviction for mail fraud, after which he was deported.

Back in Jamaica, Garvey prophesied that the liberation of the entire African diaspora would be sparked by the crowning of a black king in Africa. He founded his claim in an interpretation of the Book of Revelation, which foretells the rise of the Lion of Judah. When the Ethiopian regent Ras Tafari Makonnen became Emperor Haile Selassie I in 1930, therefore, Garvey and others believed that the prophecy had been fulfilled. Selassie, whose full title includes the designation “Lion of the Tribe of Judah,” traced his own lineage back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Selassie himself was an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian, and he disdained the prophecies that were emanating from the New World. In Jamaica, however, Selassie’s coronation sparked a wave of renewed black pride and confidence that the end of colonial oppression must be at hand. Selassie’s former title and name soon lent itself to the new movement, which was part political ideology and part religion.

Rastafarians adhere to the teachings of the Bible, which they believe to have originally been written in an Ethiopian language. They reject colonial domination and seek to recover a shared black identity. However, there is no centralized authority within the Rastafarian community, and there are no administrative hierarchies or orthodox beliefs. Rastafarians are not even agreed about the identity of Emperor Haile Selassie: Some believe that he is Christ reincarnate, while others regard him as a prophet. (The fact that Selassie was assassinated in 1974 led some to lose their faith, but devout followers maintained either that his death had been faked or that he survived in a spiritual form.)

Despite the negligible status of Rastafarianism as a religion (there are at most one million practitioners around the world), it has attracted significant attention due to the popular success of reggae music. Many Jamaican musicians of the 1960s found themselves drawn to the ideology, and reggae music soon came to embody Rastafarian identity and beliefs. Rastafarians were also quick to establish a wide variety of symbols—the green, yellow, and red colors of the Ethiopian flag, dreadlocks, and cannabis use—that helped identify practitioners to the larger community. All of these symbols came to be associated with reggae as well. When reggae gained popularity abroad following the success of the 1973 film The Harder They Come, a wide variety of cultural symbols were therefore available for use in identifying and promoting the new musical style.

For most people, it is the sound of reggae music that initially attracts them to the genre. All reggae songs have a moderate, laid-back tempo. They are in quadruple meter, but the emphasis is on the off-beat, which is usually marked by two sharply articulated strums on the electric guitar. The bass also plays an important role, accentuating strong beats and contributing countermelodies, while the drums hold the groove in place. Other typical instruments include the electric organ, which often fulfills a similar role to that of the guitar, and jazz-derived horns including the saxophone and trumpet.

The rhythms in reggae emerge from the interactions of these various instruments, each of which contributes one element to a complex groove. No single instrument is responsible for the rhythmic character of a song, but each has a unique role in sustaining the beat. At the same time, individual players are free to vary their rhythms, the result of which is a flexible groove that shifts in form while maintaining its essential identity. In reggae, various rhythmic patterns—termed “riddims”—have specific names and coded meanings, known only to those initiated into the tradition. The essential structure of the rhythmic texture, however, is derived from African practices and can be found in various musical traditions of the African diaspora.

We will hear this type of groove in our recording of “Get Up, Stand Up.” Before considering the sound the the song, however, we must address the lyrics. The message of “Get Up, Stand Up” is embodied in its short chorus, which calls on the listener to “stand up for your rights,” with the added encouragement, “don’t give up the fight!” All three verses also conclude with the “stand up for your rights” refrain, which echoes both the text and music of the chorus.

While the chorus and concluding refrains are unambiguous, the three verses contain references to the Rastafarian belief system that might be lost on the uninitiated. The first verse opens with a derisive reference to a “preacher man,” who symbolizes the institutionalized (and white) Christian church, which Rastafarians regard as an oppressive force. It continues on to warn that “not all that glitters is gold,” a reflection of the Rastafarian disdain for worldly possessions. The second verse mocks those who await the second coming of Christ, while the third makes the observation that “almighty Jah is a living man”—both expressions that rest on the common Rastafarian belief that Emperor Haile Selassie is (or was) God incarnate.

In sum, therefore, “Get Up, Stand Up” is a song steeped in the Rastafarian tradition that calls for the listener to pursue both spiritual and political freedom.

The call to protest embodied in its chorus is broad and might be applied to any number of specific situations. The verses, however, outline a uniquely Rastafarian worldview that few listeners are likely to accept. In this way, “Get Up, Stand Up” might be considered a deeply flawed protest song, for it seems to be intimately tied to the time and place of its origin. While “Blowin’ in the Wind” could be about any war or any oppressive situation, “Get Up, Stand Up” is explicitly about the Jamaican experience.

The creators of “Get Up, Stand Up,” however, would not have seen this specificity as a flaw. They were committed to giving voice to the oppressed among the African diaspora, and they couldn’t care less about whether their song could be conveniently exploited by others. “Get Up, Stand Up” was the creation of two of reggae’s chief architects, Bob Marley (1945-1981) and Peter Tosh (1944-1987). The song was initially inspired by the suffering of impoverished Haitians, whose condition Marley witnessed when touring the island in the early 1970s. Marley recorded several versions of the song with his group, The Wailers, while Tosh released his own solo version. We will consider the first recording of “Get Up, Stand Up,” which appeared on The Wailers’ 1973 album Burnin’.

The track begins with a few drum hits, after which the basic pulse is established by various electric guitars. The groove—with all of its parts in place—enters along with Marley’s voice. Although most of the instruments in the band are occupied with the groove, a guitar—the sound of which is processed by a “wah-wah” pedal— occasionally interjects melodic riffs, while an electric bass periodically fills in between sung phrases. Marley’s voice is recorded on several tracks, which allows him to converse with himself in a call-and-response style: While one Marley sings the chorus, another provides encouragement. His informal yet impassioned vocal delivery is meant to connect emotionally with the listener and spur them into action. The idea of collectivity is reinforced by double-tracking on the chorus. Because we actually hear more than one voice singing the call to protest, we easily imagine a crowd—and just as easily join in ourselves. The chorus, after all, is very easy to sing. It contains only four pitches, and the melody outlines the stepwise ascent of a scale.

In this video, we see Peter Yarrow leading a sing-along of “Blowin’ in the Wind” at a 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest.

In this video, a recording of “Get Up, Stand Up” is played at the 2011 teachers’ strike in Madison, WI.

The harmonies, likewise, are easy to play. The entire song essentially rests on a single minor triad—a harmony that reinforces the seriousness of the song’s message, and that literally anyone could provide using a guitar or piano. Here, however, we run into some difficulty, for while it is easy to replicate the harmony and melody of the chorus to “Get Up, Stand Up,” it is very difficult to replicate the style. To do so requires a broad array of electric instruments, each played by an expert with perfect timing and a deep knowledge of their role in the groove. This can only be accomplished in a staged setting. While Peter Yarrow was able to strum his guitar and lead a sing-along of “Blowin’ in the Wind” at a 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest,18 for example, “Get Up, Stand Up” is more likely to be blasted over loudspeakers, as it was during the 2011 teachers’ strike in Madison, WI.19