4.2.1: Lin-Manuel Miranda - Hamilton

- Page ID

- 92110

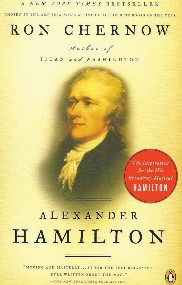

Hamilton is considered by many to be the greatest American musical theater production of the current era. The musical tells the story of Alexander Hamilton, an immigrant who travelled from the West Indies to the American colonies before the time of the American Revolution, and who came to be one of the founding fathers of the United States and the first Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington. The musical is based upon the biography by Ron Chernow (b. 1949), Alexander Hamilton, published in 2004.

Miranda and Hamilton

Hamilton is the singular creation of the actor, writer, and musician Lin-Manuel Miranda (b. 1980), who, in addition to premiering the title role, wrote the music and lyrics. Miranda is one of the biggest musical theater celebrities of his generation, having won multiple Emmys, Grammys, and Tony Awards for his music, lyrics, and performances. Much of Miranda’s work is influenced by his origins. As the child of parents of Puerto Rican descent, he grew up in a largely Latino neighborhood in Inwood, New York City, regularly visiting family in Puerto Rico. His musical preferences—Miranda grew up listening to salsa and American musicals (such as West Side Story)—reflected both an early interest in his musical heritage and a fascination with the stage. Miranda was gifted musically and academically, attending the highly competitive primary and secondary schools at Hunter College before enrolling at Wesleyan University.

In his theatrical work, Miranda foregrounds his multi-cultural upbringing and Latino identity. As a director, he has always made a conscious decision to cast actors from various cultural and racial backgrounds. This feature of Hamilton has created some controversy, given the historical fact that the men and women represented in the musical were primarily white. Miranda, however, has defended this approach by drawing parallels between his casting and musical decisions. Just as he did not attempt to write music in the style of the 1770s, he did not attempt to create a visual image representative of the 1770s. Miranda’s Hamilton was created to represent America in the current age. He makes the point that the United States was founded by immigrants. The founding fathers themselves—despite their skin color—were either immigrants or the children or grandchildren of immigrants. Hamilton himself was born in the West Indies, coming to America at a young age to make a name for himself. What is more American than that?

The musical numbers in Hamilton incorporate hip-hop beats and rap. The use of popular styles in a musical is not unique to

Hamilton: Hair (1967) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) were the first modern- era musicals to incorporate rock styles, and Lin-Manuel Miranda had already used rap and hip-hop in his first musical, In the Heights (on Broadway from 2008 to 2011). In writing Hamilton, Miranda found that rap was not only musically exciting but also very useful, for he was able to fit more words into a shorter span of time. Hamilton the man was known for being poetically loquacious. In addition, rap allowed Miranda to incorporate a large amount of information from Chernow’s biography, in addition to Hamilton’s own words. The entire musical is 150 minutes long, but includes over 20,000 words.

Miranda also uses music to communicate with the Hamilton audience in ways that both complement and transcend the script and stage action. One of his favorite techniques for doing so is allegory, or the use of musical sounds to signify hidden meaning. We will address several ways in which Miranda employs instruments or musical styles in an allegorical manner.

Allegory

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Introduction |

King George III of England addresses America |

|

“You say…” |

to a homophonic accompaniment of sustained piano chords in a four-chord descending pattern |

|

|

0’33” |

Verse 1 “You’ll be back…” |

The accompaniment switches to short harpsichord accents; the overall tone of the text becomes more sinister, which offers an unusual juxtaposition with happy music |

|

1’15” |

Hook “Da-da-da-da-da…” |

This catchy passage is sung to nonsense words and is reminiscent of the outro of The Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” which is similar in terms of key and melodic arc |

|

1’29” |

Bridge “You say our love is draining…” |

Stop-time accompaniment; double entendre on the word subject at 1’46” |

|

2’12” |

Verse 2 |

Same musical material as Verse 1; harpsichord “You’ll be returns to the front of the mix, one octave back, like higher than before; tempo slows, emphasizing before…” text, until the word “Love” at 2’36” |

|

2’46” |

Hook/Outro |

The performer is joined in this catchy tune by “Da-da-da-da-da. ” the rest of the cast members on stage |

There are several additional musical allegories in Hamilton. Let us consider, for example, the number “You’ll Be Back,” which is sung from the perspective of King George III. The music for this number is in the style of 1960s British Invasion pop. (Incidentally, The Beatles—the most famous and influential of the British Invasion bands—prominently featured harpsichord in their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.) Again, Miranda makes a connection between a British musical style (an invasive one at that) and an imperialistic British character. But that’s not all: Miranda further uses the pop genre to heighten the impact of his character’s words. King George sings this number to a personified America. The music is relentlessly upbeat, as if expressing the emotional state of a delirious ex-boyfriend who cannot grasp that the relationship is over. The text, which is quite disturbing at times, is hilariously juxtaposed with the some of the happiest and tuneful music of the show.

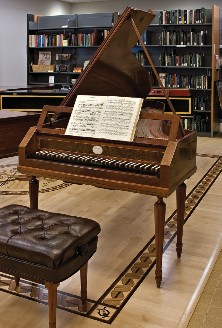

Let us also consider Miranda’s use of the harpsichord. Miranda writes for two keyboard instruments in his musical: the harpsichord and the piano. The two instruments really did not coexist in history. During the course of the 1700s, the harpsichord was gradually replaced by the fortepiano, which was itself an early predecessor to the piano. In Hamilton, however, we do not hear a fortepiano but rather a modern, 20th-century piano—an instrument historically separated from the harpsichord by over one hundred years. The harpsichord, therefore, represents an old way of life—and, more particularly, an old way of conducting politics. Specifically, Miranda uses the harpsichord to represent British rule before the revolution.

The sound of the harpsichord was, historically speaking, the sound of the 18th-century British monarchy. In order to draw a historical comparison, we might consider the music of George Frederic Handel. Handel served as music director (German: Kapellmeister) to the German Prince George of Hanover, who later became King George I of England. While living in London, Handel composed many great works for the King, most notably his Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks1. Handel was also one of the best-known and highly celebrated harpsichordists of his time. It is therefore fitting that the harpsichord should represent King George III, England, political oppression, and a deranged narcissistic ex-suitor.

We encounter this allegory in several musical examples. In “Farmer Refuted,”2 Bishop Samuel Seabury, accompanied by harpsichord, defends his decision to remain loyal to England and begs Hamilton to do the same. “You’ll Be Back” begins with King George III singing to a subdued piano accompaniment. When his lyrics turn sinister, however, we hear the harpsichord enter. In both of these cases, therefore, the sound of the harpsichord is a symbol for the old-fashioned values of the British monarchy.

G.F. Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks incorporates the harpsichord in a way that is typical of 18th-century European music.

In “Farmer Refuted,” Miranda uses the harpsichord to symbolize loyalty to England.

Cyclicism

King George later returns to perform “I Know Him.” This song is a musical reprise of the first number he sang (“You’ll Be Back”). At this point in the musical, the Revolution is long over and John Adams has been elected president. The harpsichord can still be heard, but it is less prominent than it was in “You’ll Be Back.” Instead, it is lurks behind a texture that consists primarily of strings played pizzicato. This is significant: England (harpsichord) has lost the war and King George (harpsichord) no longer rules over the Americans.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Introduction “They say…” |

Same introductory chords as the original introduction, despite plot changes |

|

0’24” |

“I’m perplexed...” |

Unusual harmonies |

|

0’42” |

“John Adams…” is spoken in surprise. |

|

|

0’45” |

Verse 1 “I know him…” |

Begins with the same tune and feel of Verse 1 from “You’ll Be Back,” but there is no harpsichord; instead, the texture consists of plucked strings, which recall the sound of the harpsichord but offer a warmer timbre; harpsichord returns to the mix in the background at 0’54” on the words, “Years ago” |

|

1’18” |

Hook |

Only one iteration of this, unlike before, and there is no “everybody” joining in |

“I Know Him” is not the only example of a musical reprise. Indeed, in crafting the score to Hamilton, Miranda sought to unify the various parts of the work using cyclical techniques. Hamilton contains many musical ideas that harken back to earlier points in the work. This approach to creating a narrative can be compared to Wagner’s use of leitmotifs. For example, the opening of the musical begins with a narrative rapped by Aaron Burr: “How does a bastard [...] grow up to be a hero and scholar?” Miranda treats this passage from Aaron Burr’s opening number, which is entitled “Alexander Hamilton,”3 as a leitmotif, which later returns in “A Winter’s Ball,” “Guns and Ships,” “What’d I Miss,” “The Adams Administration,” and “Your Obedient Servant.” Despite the recurrence of musical material, however, each of these numbers has a distinct character. In “What’d I Miss,” the borrowing takes on a swinging feel as the once-straight sixteenths of the opening become dotted. In “Your Obedient Servant,” on the other hand, the tone is darkened by tremolo strings and the omission of the snaps that were previously heard on offbeats: Burr, now downright angry, is resentful of Alexander Hamilton.

The opening phrases of “Alexander Hamilton” become a leitmotif and return throughout the work.

Success

Upon its Broadway premiere in 2015, Hamilton immediately sold out. As of 2019, it continues to be nearly impossible to secure a ticket, the aftermarket prices of which have soared to record-breaking levels. The musical is currently on tour to cities across the globe, including Puerto Rico and London, England. It has won numerous awards, including ten Lortel Awards, three Outer Critic Circle Awards, eight Drama Desk Awards, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best New Musical, and an Obie for Best New American Play.