4.2: Melodic Modes of Southwest Asia, South Central Asia, North Africa

- Page ID

- 91145

In many Middle Eastern cultures there is an aesthetic emphasis placed on the presentation of words. This is evidenced by the poetic legacy the region. This can also be heard in the melodic presentation of poetry. Singers use ornamentation and embellishment to add to the emotional content and meaning in performance. Melody is a primary element in music from this part of the world. Traditional music has no harmony and sometimes, as is the case with recitation of the Qur’an, has no steady background pulse. The expression of the emotions in a melody is a highly developed skill.

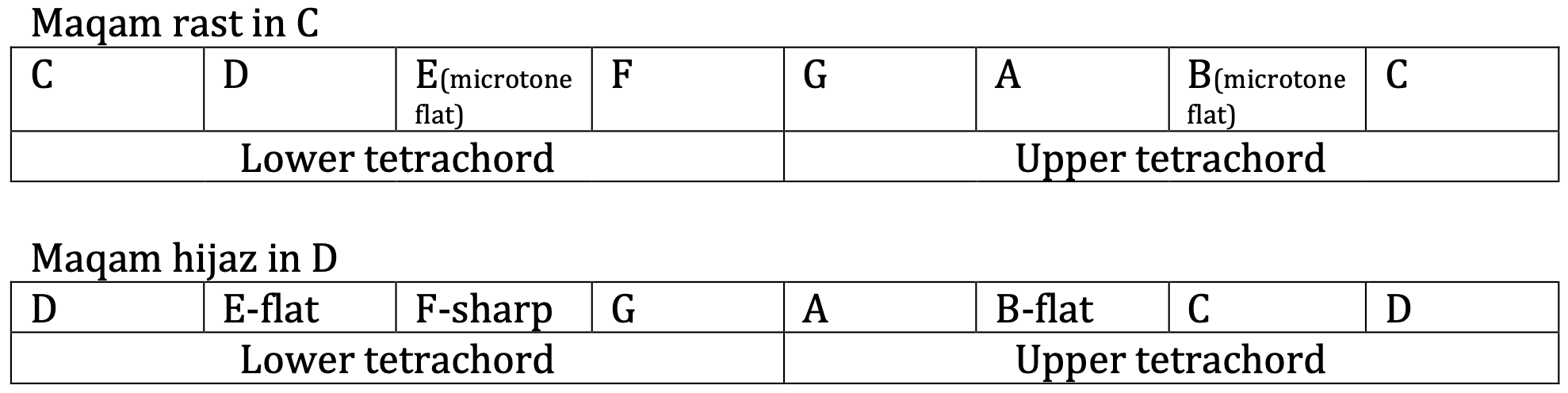

Instead of dividing the octave into 12 semitones, Middle Eastern music has 24 microtones to choose from. This allows for more nuanced melodic variation than in the Western musical world. It also causes much music from this tradition to sound “out of tune” from a Western perspective. These microtones (or quartertones) exist between the notes of a piano and other Western instruments. Therefore much Middle Eastern music cannot be represented or recreated using Western instruments and notation. For instance: The notes of Maqam Rast melodic mode and the C major scale can be seen in Figure 6. Note that a piano cannot produce the quarter flat E and B.

The term for the scales of the Arabic, Persian, Jewish, and Turkish musical world is maqam. Maqam are not simply scales like in the west. Instead they are melodic modes that have extra musical/emotional associations. Like Western scales maqam usually divide the octave into seven notes (heptonic). Unlike in the Western musical world, maqam are not thought of as one grouping of seven but instead they are most often two four-note tetrachords that are stacked on top of each other. The lowest note in the lower tetrachord is an octave below the highest note in the upper tetrachord. The most important note (tonic) is the first note of the lower tetrachord and the second most important note (dominant) is the first note of the upper tetrachord. In any one piece there may be a variety of tetrachords used for differing sections. Each tetrachord has its own expressive qualities and extra-musical associations. Categories of maqam are based upon their lower tetrachords (regardless of the variety of upper tetrachords). The Figure 6 shows two of the more common maqam using western letter names with the tetrachords.

Indian Raga

In India the set of pitches from which a piece is conceived is known as a raga. There are many Hindustani (north Indian) and Carnatic (South Indian) ragas. Each of them dictates both the notes that performers will choose for the melody and also rules for how the performer will perform these notes. Most ragas contain seven ascending pitches with a differing seven descending pitches within an octave. Like music from the Arabic world extra-musical associations, microtones and ornamentations are important components of the performance of ragas. Specific ragas are associated with times of the day and seasons of the year. In addition to having a “road map” for improvisation each raga also has a repertoire of pre- composed melodies that are passed down orally through the tradition. Aside from these small “compositions” no two performances of a raga will be exactly alike.

Much Indian “classical” music is based on a long improvisation of melody on the given raga and rhythmic tala being performed. In Hindustani culture a common ensemble performing a raga would consist of a sitar, a tambura, and tabla. In Carnatic traditions the ensemble would also be a trio but the common instrumentation would include a vina, tambura, and mrdangam. In each of these ensembles the main chordophone instrument performs the raga (sitar, vina) while the drums and drones accompany. In the Carnatic tradition the human voice plays a more prominent role in the music. When the voice sings a raga it usually uses a solfege system called sargam in which the singer uses the following syllables: sa, ra/ri, ga, ma, pa, dha , da/ni, sa. Like in other examples of scales there is a hierarchy of notes with sa acting as the equivalent of the Western tonic. To someone not familiar with the practice or the language it might appear that the singer is speaking words with meaning. That is not the case, the syllables simply indicate pitch height.

Analyzing melody:

- What instrument is performing the melody?

- Is the melody pre-composed or is it improvised? Is it ornamented?

- What scale or melodic mode serves as the foundation for the melody?

- Describe the range, direction, and motion of the melody.