5.1: Sonata Form - Introduction to Sonata Theory

- Page ID

- 61951

A classical sonata is a multi-movement work for solo instrument, chamber ensemble, or orchestra with at least one movement in sonata form. Almost always, the first movement of a sonata is in sonata form. The last movement is typically an upbeat finale, which can be in a number of different forms. Inner movements (second movement of a three-movement sonata; second and third movements of a four-movement sonata) are typically slow movements and/or dance movements (minuets or scherzos). Any non-dance movement in a sonata can take sonata form, but rarely all of them at once. Commonly, only the first movement takes sonata form, or the first and one other movement. The other movements will take other standard forms, such as minuet/trio, theme-and-variations, rondo, or sonata-rondo. In this unit, we will focus on sonata forms, particularly as they are found in first movements of instrumental sonatas.

Sonata form

Sonata form shares many structural properties with small ternary form (specifically the rounded binary variant). That is, the core music of a sonata movement can be understood as exhibiting a large, three-part pattern of ABA’.

However, like small ternary, a sonata-form movement also has a two-part structure, with the first A section forming the first “half” of the movement, and the B and A’ sections working together to form the second “half.” This is most obviously seen in early sonata movements, which repeat each of those two parts. This is called a double-reprise structure, and on this level looks exactly like a rounded-binary theme.

||: A :||: B A’ :||

which sounds like

AABA’BA’

Later sonatas shed the repeat of the second reprise, only repeating the first reprise.

||: A :|| B A’ ||

which sounds like

AABA’

Still later sonatas often shed both sets of repeats, making the binary aspect of the structure much less obvious (if it even exists) than the ternary aspect of the structure.

|| A || B A’ ||

which sounds like

ABA’

The A section (or module) exhibits what we call exposition function, and the A’ section exhibits recapitulation function. (These are the same names as other small ternary forms, like a minuet or the theme of a theme-and-variations movement.) The B section exhibits what we call development function. (This differs from the contrasting middle of other small ternary forms.) These functions will be briefly defined below and explored in greater detail in other resources.

As in minuets, it is common and acceptable to refer to the A section as “the exposition,” the B section as “the development,” and the A’ section as “the recapitulation,” as long as we retain the conceptual difference between formal modules (the passages of music) and formal functions (what those passages do in the context of the larger musical structure).

Formal functions in a sonata movement

Exposition function involves three important features:

- establish the home-key tonality;

- move to and establish a secondary key by means of a strong cadence (PAC), called the essential expositional closure (EEC); and

- lay out the melodic themes and thematic cycle that will form the foundation for the rest of the movement.

We can think about this as a question, or at least an incomplete statement: all the main melodic material of the movement is presented, but it ends in the “wrong” key.

Development function highlights the openness of this question by cycling through the same melodies in the same order, exploring the instability of the secondary key. This exploration can be accomplished by any of the following:

- beginning in the secondary key, but modulating to another key before achieving a cadence;

- employing non-functional harmonic progressions, such as harmonic sequences;

- frequent modulation; or

- multiple tonal goals other than the home key or secondary key.

It then intensifies the need for an “answer” by progressing toward an active dominant (an HC or a major arrival on V or V7) in the home key.

If exposition function presents a “question,” and development function explores and then intensifies this question, recapitulation function answers the question. Recapitulation function does this by progressing one last time through the thematic cycle, but this time bringing it to a satisfactory completion: a PAC in the home key, called the essential sonata closure (ESC).

Cadential goals

As hinted at above, sonata form is anchored around several important cadences. They serve as signposts for the formal structure, as well as goals of the music leading into them. We will note these cadences using a Roman numeral for the key (relative to the home key) followed by a colon and the type of cadence.

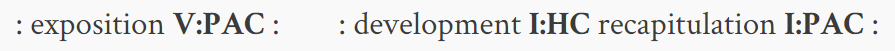

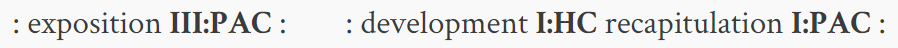

As in small ternary form, the exposition tends to end with a PAC in a secondary key (V:PAC in a major-key movement, III:PAC or v:PAC in a minor-key movement). Rather than being simply a norm, though, this cadence is essential to the form. This PAC is called the essential expositional closure, or EEC.

The recapitulation has a corresponding cadence, also familiar from small ternary form: a PAC in the home key, which tends to correspond thematically with the EEC. This I:PAC is called the essential sonata closure, or ESC.

The development section, like the contrasting middle in small ternary form, typically ends with a HC in the home key (I:HC) or a dominant arrival in the home key, which prepares the arrival of the recapitulation.

or

Commonly, the exposition and recapitulation each have an additional cadential goal that is not shared with other small-ternary-like forms. These goals each occur between the beginning of the module and the cadential goal (EEC or ESC), and they often—though not always—involve a pause or stoppage of melodic or harmonic motion. Thus, each of these halfway cadences is called a medial caesura (MC). Both PACs and HCs, in the home key or in a secondary key, can function as medial caesurae.

Defaults and deformations

Sonata form is not a single recipe for structuring a movement. It is a set of norms that are almost always violated, or at least altered, in some way in a composition. Thus, we can talk about individual pieces being “in dialog with” sonata norms. That is, they incorporate enough of the definitive elements to be considered “in sonata form,” but they carry enough unique elements to cause some tension with the norms. Over time, some of the unique elements used by classical composers were adopted by others and became norms for a later generation. Thus, even the “typical” sonata movement is different at different times and places in history.

In general, though, for each element of sonata form, we can identify default properties of that element. Sometimes there are multiple possibilities that can be considered normative. For example, the most common cadence used for the MC of a classical sonata movement is V:HC. This is called the first-level default. The second most common MC cadence is a I:HC—the second-level default. Where multiple possibilities are normative, but one is more common or preferred over another, we use this language.

Non-default properties of a particular sonata movement are called deformations. For example, a II:IAC MC is not at all typical of classical sonatas. Thus, we would consider it a deformation. It does not mean that a II:IAC cannot function as an MC (though I can’t think of an example). However, it means that a II:IAC is a purposeful move by the composer to contradict the norm. As such, any analysis should address this deformation and attempt to explain its musical and historical significance.

Auxiliary modules

Often the exposition–development–recapitulation structure is framed by an introduction and/or a coda. Though important musical activity can take place in these modules, they are outside the sonata proper. The essential sonata elements, as well as the ones that are similar enough from piece to piece that we can generalize about them well, take place in the exposition, development, and recapitulation. Though we will address introduction and coda materials during in-class analyses, and you should address them in your own analyses, the properties of those modules are not covered by these online resources.

Further details

The remaining sonata resources on this website are largely in reference format. Rather than walk through the details in the manner of a typical textbook, they will provide you with the defining features of the elements described in as concise a manner possible. This consision will serve you well when referencing these resources quickly during analytical activities. However, it will also force you to wrestle with them in the context of real pieces in order to understand them fully. If you simply read these resources, you will not understand sonata form. You must make use of them while listening to and analyzing music in order to assimilate the information and develop the skills necessary to apply them musically.