6.8: Voice

- Page ID

- 40441

Voice

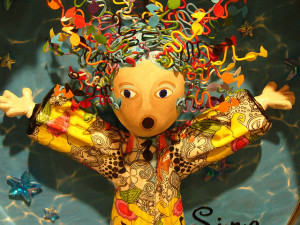

Image by Kathleen Tyler Conklin: CC BY: Attribution

The speaker is the bridge between the poem’s experience and the reader. Similar to language, when it works best, it becomes invisible, cemented to, part and particle of the poem’s experience. Tone of voice is responsible for creating trust between the reader and the speaker, in seducing the reader to lose him or herself in the experience; it is responsible for letting a reader be enraptured by the poem.

In the introduction to the 2006 Best American Poetry anthology, the judge for that year, poet Billy Collins, explains the key role that a poem’s tone of voice played in determining which poems to place in the pile that left him “cold” and which poems to place in the pile that caught him “in their spell,” those that he would eventually consider for inclusion in the collection. Collins begins by elucidating how the voice of a poem took on a bigger role once Modern poetry began to experiment with free verse:

Once Walt Whitman demonstrated that poetry in English could get along without standard meter and end-rhyme, poetry began to lose that familiar gait and musical jauntiness that listeners and readers had come to identify with it. But poetry also lost something more: a trust system that had bound poet and reader together through the reliable recurrence of similar sounds and a steady dependable beat. Whatever emotional or intellectual demands a poem placed on the reader, at least the reader could put trust in the poet’s implicit promise to keep up a tempo and maintain a sound pattern. It is the same promise that is made to the listeners of popular songs. What has come to replace that system of trust, if anything? However vague a substitute, the answer is probably tone of voice. As a reader, I come to trust or distrust the authority of the poem after reading just a few lines. Do I hear a voice that’s making reasonable claims for itself—usually a first-person voice speaking fallibly but honestly—or does the poem begin with a grandiose pronouncement, a riddle, or an intimate confession foisted on me by a stranger? Tone may be the most elusive aspect of written language, but our ears instantly recognize words that sound authentic and words that ring false. The character of the speaker’s voice played an indescribable but essential role in the making of those two piles I mentioned, one much taller than the other.

It is interesting that Collins refers negatively to the “voice of a stranger,” as aren’t all speakers of poems strangers to a reader? We do not know the poet, so how can we possibly know the speaker? Yet here, Collins suggests that there is something in us that does know something of the speaker, some credibility that “sounds authentic” rather than “ringing false,” and this has more to do with tone of voice than subject matter. After all, who believes someone who doesn’t sound trustworthy? It is like watching a play with bad acting — you can’t lose yourself in the story or character, you cannot transport, you cannot release yourself to get “caught in its spell.” We have trouble trusting our senses and giving our time to the speaker without suspicion, which acts as a barrier between the reader and the experience. It is similar to what poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge called a “suspension of disbelief,” in a sense: We need to be willing to be wrapped up in a poem’s experience and if we’re untrusting then we’re not willing. Tone of voice develops from the many moves a poem makes and can be considered, in another way, the stance the speaker takes, the relationship between the subject matter and the speaker.

Exercise 6.8.1

Is the speaker in a poem one and the same as the writer? Stop and consider this for a few moments. Can you think of any poems you have read where a writer has created a character, or persona, whose voice we hear when we read?

Wordsworth’s The Prelude was written as an autobiographical poem, but there are many instances where it is obvious that poet and persona are different. Charlotte Mew’s poem "The Farmer’s Bride" (1916) begins like this:

Three summers since I chose a maid,

Too young maybe — but more’s to do

At harvest-time than bide and woo.

When us was wed she turned afraid

Of love and me and all things human;

(Warner, 1981, pp. 1–2)

- Answer

-

Mew invents a male character here, and clearly separates herself as a writer from the voice in her poem. Some of the most well-known created characters—or personae—in poetry are Browning’s dramatic monologues.

Exercise 6.8.1

Analysis of Voice in Browning's Poetry

Consider the opening lines from three Robert Browning poems below. Robert Browning was one of the most important poets of the Victorian period (1812-1889). Who do you think is speaking?

Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister (1842)

Gr-r- r — there go, my heart’s abhorrence!

Water your damned flower-pots, do!

If hate killed men, Brother Lawrence,

God’s blood, would not mine kill you!

What? your myrtle-bush wants trimming?

Oh, that rose has prior claims —

Needs its leaden vase filled brimming?

Hell dry you up with its flames!

The Last Duchess (1842)

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Porphyria's Lover (1842)

The rain set early in to-night,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

- Answer

-

Well, the first speaker isn't named, but we can infer that, like Brother Lawrence whom he hates, he's a monk. The second must be a Duke since he refers to his "last Duchess" and, if we read to the end of the third poem, we discover that the speaker is a man consumed with such jealousy that he strangles his beloved Porphyria with her own hair. Each of the poems is written in the first person ("my heart’s abhorrence"; "That’s my last Duchess"; "I listened with heart fit to break"). None of the characters Browning created in these poems bears any resemblance to him: the whole point of a dramatic monologue is the creation of a character who is most definitely not the poet. Charlotte Mew’s poem can be described in the same way.

Contributors and Attributions

- "Voice" section Adapted from "Chapter Four: Voice" Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations by Michelle Bonczek Evory under the license CC BY-NC-SA

- Exercises Adapted from "8: Voice" from "Approaching Poetry" by Dr. Sue Asbee. Provided by OpenLearn, The Open University. License: CC-NC-SA