1.4: A Journal of the Plague Year- Bubonic Plague in London, 1665

- Page ID

- 55873

A Journal of the Plague Year: Bubonic Plague in London, 1665

By Daniel Defoe

Introduction:

Daniel Defoe ( c. 1660 – 1731) was an English writer, journalist, and trader. He is best known for his 1719 novel, Robinson Crusoe . In 1722, Defoe published A Journal of the Plague Year, a detailed account of a man living through the Great Plague of London in the year 1665. Defoe was only five years old in 1665 when the Great Plague took place, and the book itself was published under the initials H. F. and is probably based on the journals of Defoe's uncle, Henry Foe, who, like 'H. F.', was a saddler who lived in the Whitechapel district of East London.

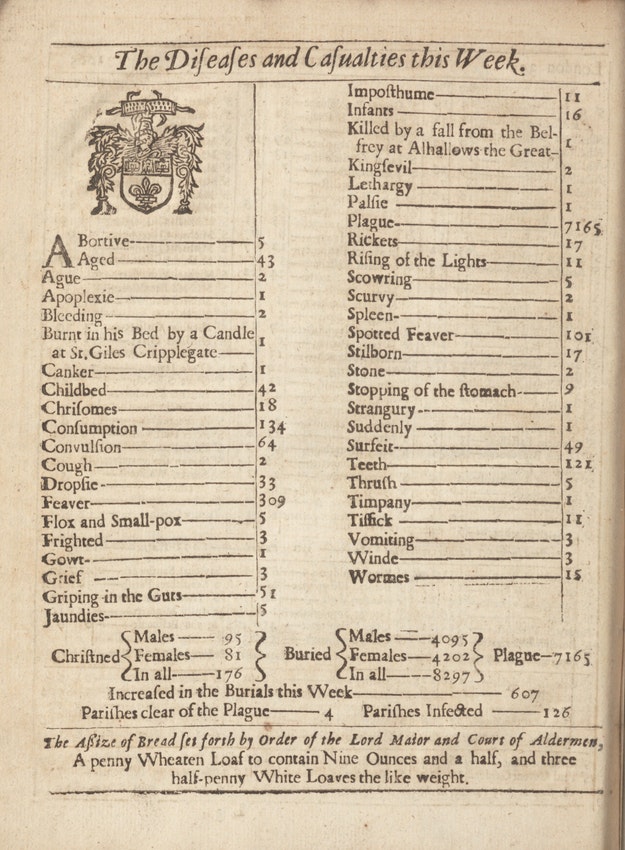

London in 1665 was a walled city with very poor sanitary conditions which created an environment ideal for the rats and fleas that carried bubonic plague. In seven months, almost one quarter of London's population (one out of every four Londoners) died from the plague. At its worst, in September of 1665, the plague killed 7,165 people in one week. Defoe’s descriptions of life during that year are vivid and detailed. Even though he was not an actual eyewitness to the plague year, his account is a valuable resource in understanding the social dynamics and human costs of the event.

Again, the public showed that they would bear their share in these things; the very court, which was then gay and luxurious, put on a face of just concern for the public

danger. All the plays and interludes, which, after the manner of the French court, had been set up and began to increase among us, were forbidden to act; the gaming- tables, public dancing rooms, and music houses, which multiplied and began to debauch the manners of the people, were shut up and suppressed; and the jack-puddings, merry-andrews, puppet-shows, rope-dancers, and such-like doings, which had bewitched the common people, shut their shops, finding indeed no trade, for the minds of the people were agitated with other things, and a kind of sadness and horror at these things sat upon the countenances even of the common people; death was before their eyes, and everybody began to think of their graves,' not of mirth and diversions.

But even these wholesome reflections, which, rightly managed, would have most happily led the people to fall upon their knees, make confession of their sins, and look up to their merciful Saviour for pardon, imploring his compassion on them in such a time of their distress, by which we might have been as a second Nineveh,had a quite contrary extreme in the common people: who, ignorant and stupid in their reflections, as they were brutishly wicked and thoughtless before, were now led by their fright to extremes of folly; and, as I said before, that they ran to conjurers and witches and all sorts of deceivers, to know what should become of them, who fed their fears and kept them always alarmed and awake, on purpose to delude them and pick their pockets, so they were as mad upon their running after quacks and

"The black death in London" by Unknown is in the Public Domain

mountebanks and every practising old woman for medicines and remedies, storing themselves with such multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called, that they not only spent their money but poisoned themselves beforehand for fear of the poison of the infection, and prepared their bodies for the plague instead of pressing them against it. On the other hand, it was incredible, and scarce to be imagined, how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctors' bills, and papers of ignorant fellows quacking and tampering in physic, and inviting people to come to them for remedies, which was generally set off with such flourishes as these: “INFALLIBLE preventative pills against the plague.” “NEVER-FAILING preservatives against the infection.” “SOVEREIGN cordials against the corruption of air.” “EXACT regulations for the conduct of the body in case of infection.” “Anti Pestilential pills.” “INCOMPARABLE drink against the plague, never found out before.” “An UNIVERSAL remedy for the plague.” “The ONLY TRUE plague-water.” “The ROYAL ANTIDOTE against all kinds of infection” and such a number more that I cannot reckon up, and, if I could, would fill a book of themselves to set them down.

. . . .

I had in my family only an ancient woman, that managed the house, a maid-servant, two apprentices, and myself, and the plague beginning to increase about us, I had

many sad thoughts about what course I should take, and how I should act; the many dismal objects which happened everywhere, as I went about the streets, had filled

my mind with a great deal of horror, for fear of the distemper itself, which was, indeed, very horrible in itself, and in some more than others; the swellings, which were generally in the neck or groin, when they grew hard, and would not break, grew so painful that it was equal to the most exquisite torture; and some, not able to bear the torment, threw themselves out at windows, or shot themselves, or otherwise made themselves away, and I saw several dismal objects of that kind: others, unable to contain themselves, vented their pain by incessant roarings, and such loud and lamentable cries were to be heard, as we walked along the streets, that would pierce the very heart to think of, especially when it was to be considered that

the same dreadful scourge might be expected every moment to seize upon ourselves.

I cannot say but that now I began to faint in my resolutions; my heart failed me very much, and sorely I repented of my rashness, when I had been out, and met with

such terrible things as these I have talked of; I say, I repented my rashness in venturing to abide in town, and I wished, often, that I had not taken upon me to stay, but had gone away with my brother and his family.

Terrified by those frightful objects, I would retire home sometimes, and resolve to go out no more, and perhaps I would keep those resolutions for three or four days, which time I spent in the most serious thankfulness for my preservation, and the preservation of my family, and the constant confession of my sins, giving myself up to God every day, and applying to him with fasting and humiliation and meditation. Such intervals as I had, I employed in reading books, and in writing down my memorandums of what occurred to me every day, and out of which, afterwards, I took most of this work, as it relates to my observations without doors . . . .

I had a very good friend, a physician, whose name was Heath, whom I frequently visited during this dismal time, and to whose advice I was very much obliged for many things which he directed me to take by way of preventing the infection when I went out, as he found I frequently did, and to hold in my mouth, when I was in the streets; he also came very often to see me, and as he was a good Christian, as well as a good physician, his agreeable conversation was a very great support to me, in the worst of this terrible time.

It was now the beginning of August, and the plague grew very violent and terrible in the place where I lived, and Dr. Heath, coming to visit me and finding that I ventured so often out in the streets, earnestly persuaded me to lock myself up, and my family, and not to suffer any of us to go out of doors; to keep all our windows fast, shutters and curtains close, and never to open them, but first to make a very strong smoke in the room, where the window or door was to be opened, with rosin and pitch, brimstone and gunpowder, and the like, and we did this for some time, but as I had not laid in a store of provision for such a retreat, it was impossible that we could keep within doors entirely; however, I attempted, though it was so very late, to do something towards it; and first, as I had convenience both for brewing and baking, I went and bought two sacks of meal, and for several weeks, having an oven, we baked all our own bread; also I bought malt, and brewed as much beer as all the casks I had would hold, and which seemed enough to serve my house for five or six

weeks; also, I laid in a quantity of salt butter and Cheshire cheese; but I had no flesh meat, and the plague raged so violently among the butchers and slaughter-

houses, on the other side of our street, where they are known to dwell in great numbers, that it was not advisable so much as to go over the street among them.

And here I must observe again that this necessity of going out of our houses to buy provisions, was in a great measure the ruin of the whole city, for the people catched

the distemper, on these occasions, one of another, and even the provisions themselves were often tainted, at least I have great reason to believe so; and, therefore, I cannot say with satisfaction, what I know is repeated with great

assurance, that the market people, and such as brought provisions to town, were never infected. I am certain the butchers of Whitechapel, where the greatest part of the flesh meat was killed, were dreadfully visited, and that at last to such a degree that few of their shops were kept open, and those that remained of them killed their meat at Mile End, and that way, and brought it to market upon horses.

However, the poor people could not lay up provisions, and there was a necessity that they must go to market to buy, and others to send servants, or their children; and,

as this was a necessity which renewed itself daily, it brought abundance of unsound people to the markets, and a great many that went thither sound, brought death home with them.

It is true, people used all possible precaution ; when any one bought a joint of meat in the market, they would not take it out of the butcher's hand, but took it off the hooks themselves. On the other hand, the butcher would not touch the money, but have it put into a pot full of vinegar, which he kept for that purpose. The buyer carried always small money to make up any odd sum, that they might take no change. They carried bottles for scents and perfumes in their hands, and all the means that could be used were employed; but then the poor could not do even these things, and they went at all hazards.

. . . .

But now the fury of the distemper increased to such a degree, that even the markets were but very thinly furnished with provisions, or frequented with buyers, compared to what they were before; and the lord mayor caused the country people who brought provisions, to be stopped in the streets leading into the town, and to sit down there with their goods, where they sold what they brought, and went immediately away; and this encouraged the country people greatly to do so, for they sold their provisions at the very entrances into the town, and even in the fields; us, particularly, in the fields beyond Whitechapel, in Spitalfields.

. . . .

As for my little family, having thus, as I have said, laid in a store of bread, butter, cheese, and beer, I took my friend and physician's advice,' and locked myself up, and my family, and resolved to suffer the hardship of living a few months without flesh meat, rather than to purchase it at the hazard of our lives.

. . . .

At the beginning of the plague, when there was now no more hope but that the whole city would be visited; when, as I have said, all that had friends or estates in the country retired with their families, and when, indeed, one would have thought the very city itself was running out of the gates, and that there would be nobody left behind, you may be sure, from that hour, all trade except such as related to immediate subsistence, was, as it were, at a full stop.

This is so striking a circumstance and contains in it so much of the real condition of the people, that I think I cannot be too particular in it; and, therefore, I descend to the several arrangements or classes of people who fell into immediate

distress upon this occasion. For example,

1. All master workmen in manufactures; especially such as belonged to ornament, and the less necessary parts of the people's dress, clothes, and furniture for houses; such as ribband weavers and other weavers, gold and silver lace makers, and gold and silver wire drawers, seamstresses, milliners, shoemakers, hat-makers, and glove-makers; also upholsterers, joiners, cabinet-makers, looking-glass-makers, and innumerable trades which depend upon such as these. I say the master workmen in such stopped their work, dismissed their journeymen and workmen, and all their dependents.

Bill of mortality for the week of 19th–26th September 1665, which saw the highest death toll from plague.

"The diseases and casualities of this week" by Public Domain Review is in the Public Domain

2. As merchandising was at a full stop (for very few ships ventured to come up the river, and none at all went out), so all the extraordinary officers of the customs, like-

wise the watermen, cartmen , porters, and all the poor whose labour depended upon the merchants, were at once dismissed, and put out of business.

3. All the tradesmen usually employed in building or repairing of houses were at a full stop, for the people were far from wanting to build houses, when so many thousand

houses were at once stript of their inhabitants; so that [in this particular set of circumstances] turned out all the ordinary workmen of that kind of business, such as bricklayers, masons, carpenters, joiners, plasterers, painters, glaziers, smiths, plumbers, and all the labourers depending on such.

4. As navigation was at a stop, our ships neither coming in or going out as before, so the seamen were all out of employment, and many of them in the last and lowest degree of distress; and with the seamen were all. the several tradesmen and workmen belonging to and depending upon the building and fitting out of ships; such as ship-carpenters, calkers, rope-makers, dry coopers, sail-makers, anchor-smiths and other smiths; block-makers, carvers, gunsmiths, ship-chandlers, ship-carvers, and the like. The masters of those, perhaps, might live upon their substance, but the traders were universally at a stop, and consequently all their workmen discharged. Add to these, that the river was in a manner without boats, and all or most part of the watermen, lightermen, boat-builders, and lighter builders, in like manner idle, and laid by.

5. All families retrenched their living as much as possible, as well those that fled as those that stayed; so that an innumerable multitude of footmen, serving men, shop-

keepers, journeymen, merchants' book-keepers, and such sort of people, and especially poor maid-servants, were turned off, and left friendless and helpless without employment and without habitation; and this was really a dismal article.

I might be more particular as to this part, but it may suffice to mention, in general, all trades being stopped, employment ceased, the labour, and, by that, the bread of the

poor, were cut off; and at first, indeed, the cries of the poor were most lamentable to hear; though, by the distribution of charity, their misery that way was gently abated.

Many, indeed, fled into the country; but thousands of them having stayed in London, till nothing but desperation sent them away, death overtook them on the road, and

they served for no better than the messengers of death; indeed, others carrying the infection along with them, spread it very unhappily into the remotest parts of the

kingdom.

The women and servants that were turned off from their places were employed as nurses to tend the sick in all places; and this took off a very great number of them.

And which though a melancholy article in itself, yet was a deliverance in its kind, namely, the plague, which raged in a dreadful manner from the middle of August to

the middle of October, carried off in that time thirty or forty thousand of these very people, which, had they been left, would certainly have been an insufferable burden, by their poverty; that is to say, the whole city could not have supported the expense of them, or have provided food for them; and they would, in time, have been even driven to the necessity of plundering either the city itself, or the country adjacent, to have subsisted themselves, which would, first or last, have put the whole nation, as well as the city, into the utmost terror and confusion.

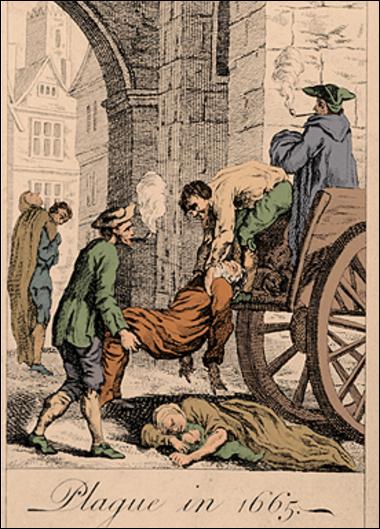

"Great plague of London-1665" by Unknown is in the Public Domain

It was observable then that this calamity of the people made them very humble; for now, for about nine weeks together, there died near a thousand a day, one day with

another; even by the account of the weekly bills, which yet, I have reason to be assured, never gave a full account by many thousands; the confusion being such, and the carts working in the dark when they carried the dead, that in some places no account at all was kept, but they worked on; the clerks and sextons not attending for weeks together, and not knowing what number they carried.

. . . .

Now, when I say that the parish officers did not give in a full account, or were not to be depended upon for their account, let any one but consider how men could be exact in such a time of dreadful distress, and when many of them were taken sick themselves, and perhaps died in the very time when their accounts were to be given in; I mean the parish-clerks, besides inferior officers; for though these poor men ventured at all hazards, yet they were far from being exempt from the common calamity; especially if it be true that the parish of Stepney had, within the year, 116 sextons, grave-diggers, and their assistants; that is to say, bearers, bell-men, and drivers of carts, for carrying off the dead bodies.

Indeed, the work was not of such a nature as to allow them leisure to take an exact tale of the dead bodies, which were all huddled together, in the dark, into a pit; which pit, or trench, no man could come nigh but at the utmost peril. I have observed often, that in the parishes of. Aidgate, Cripplegate, Whitechapel, and Stepney, there were

five, six, seven, and eight hundred in a week in the bills; whereas, if we may believe the opinion of those that lived in the city all the time, as well as I, there died sometimes two thousand a week in those parishes; and I saw it under the hand of one that made as strict an examination as he could, that there really died a hundred thousand people of the plague in it that one year; whereas, in the bills, the article of the plague was but 68,590.

. . . .

This infecting and being infected, without so much as its being known to either person, is evident from two sorts of cases, which frequently happened at that time; and there is hardly anybody living, who was in London during the infection, but must have known several of the cases of both sorts.

1. Fathers and mothers have gone about as if they had been well, and have believed themselves to be so, till they have insensibly infected and been the destruction of their whole families; which they would have been far from doing, if they had had the least apprehensions of their being unsound and dangerous themselves. A family, whose story I have heard, was thus infected by the father, and the distemper began to appear upon some of them even before he found it upon himself; but searching more narrowly, it appeared he had been infected some time, and as soon as he found that his family had been poisoned by himself, he went distracted, and would have laid violent hands upon himself, but was kept from that by those who looked

to him, and in a few days he died.

2. The other particular is, that many people having been well to the best of their own judgment, or by the best observation which they could make of themselves for several days, and only finding a decay of appetite, or a light sickness upon their stomachs; nay, some whose appetite has been strong, and even craving, and only a light pain in their heads, have sent for physicians to know what ailed them, and have been found, to their great surprise, at the brink of death, the tokens upon them, or the plague grown up to an incurable height.

It was very sad to reflect, how such a person as this last mentioned above, had been a walking destroyer, perhaps for a week or fortnight before that; how he had ruined

those that he would have hazarded his life to save; and had been breathing death upon them, even perhaps in his tender kissing and embracings of his own children. Yet thus certainly it was, and often has been, and I could give many particular cases where it has been so. If, then, the blow is thus insensibly striking; if the arrow flies thus unseen and cannot be discovered; to what purpose are all the schemes for shutting up or removing the sick people? Those schemes cannot take place but upon those that appear to be sick, or to be infected; whereas there are among them, at the same time, thousands of people who seem to be well, but are all that while carrying death with them into all companies which they come into.

This frequently puzzled our physicians, and especially the apothecaries and surgeons, who knew not how to discover the sick from the sound. They all allowed that it was really so; that many people had the plague in their very blood, and preying upon their spirits, and were in themselves but walking putrefied carcasses, whose breath was infectious, and their sweat poison, and yet were as well to look on as other people, and even knew it not themselves; I say, they all allowed that it was really true in fact, but they knew not how to propose a discovery.

Glossary:

- Court - The group that attends to and lives with the royal family, including bodyguards, relatives, amongst others.

- Dry coopers - Barrel-makers, specifically those who make barrels for dry goods such as grains, fruits, or vegetables.

- Jack-pudding - A foolish and bumbling comedic archetype of stage and street performers.

- Journeymen - A trade worker that serves under a master and often is paid daily with a fairly low skill level.

- Melancholy - A sadness or depression; something that evokes sad feelings.

- Merry-andrews - A performer who acts as a clown, often in service to another performer.

- Mile End - At the time of this document, it was a hamlet one mile from Aldgate, which marked the edge of London, which was a significant trading hub. In modern times, it’s a district of the Greater London Area.

- Mountebanks - A person who sells often fake medicines and treatments, akin to a snake-oil salesman.

- Nineveh - The historical capital of the Assyrian Empire which in Biblical tradition was utterly obliterated by God’s wrath for the Assyrian’s pride.

- Physic - An archaic term for the healing practice; medicine.

- Rope-dancers - A tightrope walker or similar acrobat.

- Rosin and pitch, brimstone and gunpowder - Rosin and pitch are solid plant resins, brimstone is a term for sulphur, and gunpowder is an explosive and fuel. When burned all of these produce heavy smoke and strong smells which would block the miasma: bad odors that doctors believed caused diseases.

- Sextons - A church official that tended to the church building and it’s graveyard.

- Spitalfields - A small field just outside London with sparse housing.

- Weekly bills - A weekly posting of local, regional, or national news that was usually posted in the town square.

- Whitechapel - At the time of this document, Whitechapel was a parish just outside London that housed less fragrant industries like slaughterhouses, foundries, and breweries.

Questions:

- What happened to many trades, businesses, and popular forms of entertainment as a result of the plague? How does that compare to what’s happening today?

- What measures did Dafoe and others take to try and protect themselves from contracting the sickness? How are those measures similar to steps people take today to protect themselves against epidemics? How are they different?

- What does Dafoe say about the death toll, and why is that reminiscent of what we’re seeing today with Covid-19?

- What major concern does Dafoe bring up, near the end of the excerpt, regarding how the disease spreads? Compare and contrast that to how modern pandemics spread.

Sources:

Defoe, Daniel. “Journal of the Plague Year.” Internet Archive , New York, London, Longmans, Green, and Co, 1 Jan. 1896, archive.org/details/cu31924003518085/page/n8/mode/2up.

“Great Plague of London.” Wikipedia , Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Apr. 2020, simple.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plague_of_London.

Irving, Clive. “Inside the Living Hell of London in the Plague Year.” The Daily Beast , 26 Feb. 2020, www.thedailybeast.com/inside-the-living-hell-of-london-in-the-plague-year.

This work (Journal of the Plague Year, by Daniel Defoe ), identified by Internet Archive , is free of known copyright restrictions.