1.3: “All human wisdom and foresight were vain-” Foreword to The Decameron

- Page ID

- 55872

istorical comparisons. For instance, though there are some similarities between the Covid-19 outbreak and the bubonic plague of the fourteenth century, there are also crucial differences in the contexts in which those diseases spread. Studying those differences helps us understand what happened in the 1300s and why, as well as what’s happening now and why. You’ll find that in addition to questions highlighting parallels, there are also questions that aim to uncover differences between the events of the past and those of the present.

We sincerely hope you find this resource helpful, and are excited to see the creative ways faculty will put this collection to good use.

Ryan Johnson

St. Clair County Community College

2.

3.

“All human wisdom and foresight were vain:” Foreword to The Decameron

By Giovanni Boccaccio

Introduction:

The Black Death is the name given to the plague that struck Europe in 1347 and lasted until 1352. The Plague reached Europe via trade routes, both land and sea, to the east, where the disease had been ravaging China since the early 1300s. Normally ascribed to bubonic plague (named after the buboes , or swellings that developed on the body), the Plague also took the pneumonic form and could be spread from person to person via coughing and sneezing, as well as the septicemic form when it entered the blood.

The Black Death was widespread, affecting people across Europe. People of all ages and social classes were killed by the disease, which wiped out as much as 40% of Europe’s total population. The Plague also devastated the Middle East and Asia, killing the populations of entire villages and towns. Even though the Black Death was the worst instance of plague, the disease would return to Europe, usually once every generation or so, for centuries.

The following excerpt comes from Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio, who lived in Italy during the plague years. The work excerpted here is from Boccaccio’s Decameron , a fictional tale of ten friends who take up residence in an abandoned church in the country outside the city of Florence. They’ve tried to isolate themselves from the disease and are passing the time telling stories. In the introduction to the Decameron , presented here, the narrator discusses the onset of the Plague on the city of Florence, as well as the many different reactions to the spread of the disease.

In the year 1348 after the fruitful incarnation of the Son of God, that most beautiful of Italian cities, noble Florence, was attacked by deadly plague. It started in the East either through the influence of the heavenly bodies or because God’s just anger with our wicked deeds sent it as a punishment to mortal men; and in a few years killed an innumerable quantity of people. Ceaselessly passing from place to place, it extended its miserable length over the West. Against this plague all human wisdom and foresight were vain. Orders had been given to cleanse the city of filth, the entry of any sick person was forbidden, much advice was given for keeping healthy; at the same time humble supplications were made to God by pious persons in processions and otherwise. And yet, in the beginning of the spring of the year mentioned, its horrible results began to appear, and in a miraculous manner. The symptoms were not the same as in the East, where a gush of blood from the nose was the plain sign of inevitable death; but it began both in men and women with certain swellings in the groin or under the armpit. They grew to the size of a small apple or an egg, more or less, and were vulgarly called tumours. In a short space of time these tumours spread from the two parts named all over the body. Soon after this the symptoms changed and black or purple spots appeared on the arms or thighs or any other part of the body, sometimes a few large ones, sometimes many little ones. These spots were a certain sign of death, just as the original tumour had been and still remained.

No doctor’s advice, no medicine could overcome or alleviate this disease. An enormous number of ignorant men and women set up as doctors in addition to those who were trained. Either the disease was such that no treatment was possible or the doctors were so ignorant that they did not know what caused it, and consequently could not administer the proper remedy. In any case very few recovered; most people died within about three days of the appearance of the tumours described above, most of them without any fever or other symptoms.

The violence of this disease was such that the sick communicate it to the healthy who came near them, just as a fire catches anything dry or oily near it. And it even went further. To speak to or go near the sick brought infection and a common death to the living; and moreover, to touch the clothes or anything else the sick had touched or worn gave the disease to the person touching.

. . . .

Some thought that moderate living and the avoidance of all superfluity would preserve them from the epidemic. They formed small communities, living entirely separate from everybody else. They shut themselves up in houses where there were no sick, eating the finest food and drinking the best wine very temperately, avoiding all excess, allowing no news or discussion of death and sickness, and passing the time in music and suchlike pleasures. Others thought just the opposite. They thought the sure cure for the plague was to drink and be merry, to go about singing and amusing themselves, satisfying every appetite they could, laughing and jesting at what happened. They put their words into practice, spent day and night going from tavern to tavern, drinking immoderately, or went into other people’s houses, doing only those things which pleased them. This they could easily do because everyone felt doomed and had abandoned his property, so that most houses became common property and any stranger who went in made use of them as if he had owned them. And with all this bestial behaviour, they avoided the sick as much as possible.

In this suffering and misery of our city, the authority of human and divine laws almost disappeared, for, like other men, the ministers and the executors of the laws were all dead or sick or shut up with their families, so that no duties were carried out. Every man was therefore able to do as he pleased.

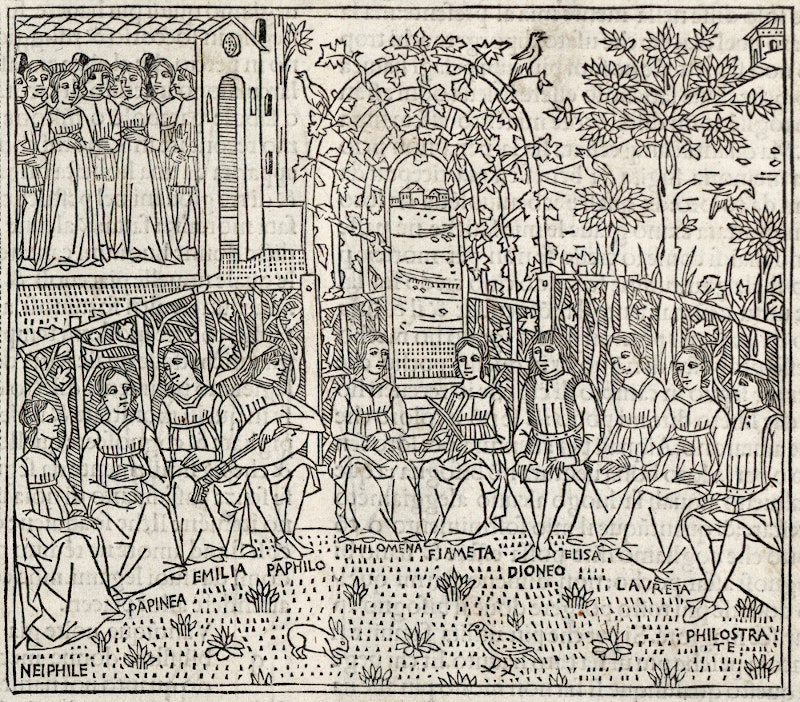

Detail from a 19th Century illustration of Boccaccio’s Decameron showing the ten young people who traveled together to escape the plague outbreak in Florence. "Decameron" is in the Public Domain

Many others adopted a course of life midway between the two just described. They did not restrict their victuals so much as the former, nor allow themselves to be drunken and dissolute like the latter, but satisfied their appetites moderately. They did not shut themselves up, but went about, carrying flowers or scented herbs or perfumes in their hands, in the belief that it was an excellent thing to comfort the brain with such odours; for the whole air was infected with the smell of dead bodies, of sick persons and medicines.

Others again held a still more cruel opinion, which they thought would keep them safe. They said that the only medicine against the plague-stricken was to go right away from them. Men and women, convinced of this and caring about nothing but themselves, abandoned their own city, their own houses, their dwellings, their relatives, their property, and went abroad or at least to the country round Florence, as if God’s wrath in punishing men’s wickedness with this plague would not follow them but strike only those who remained within the walls of the city, or as if they thought nobody in the city would remain alive and that its last hour had come.

Not everyone who adopted any of these various opinions died, nor did all escape. Some when they were still healthy had set the example of avoiding the sick, and, falling ill themselves, died untended.

One citizen avoided another, hardly any neighbour troubled about others, relatives never or hardly ever visited each other. Moreover, such terror was struck into the hearts of men and women by this calamity, that brother abandoned brother, and the uncle his nephew, and the sister her brother, and very often the wife her husband. What is even worse and nearly incredible is that fathers and mothers refused to see and tend their children, as if they had not been theirs.

Thus, a multitude of sick men and women were left without any care except from the charity of friends (but these were few), or the greed of servants, though not many of these could be had even for high wages. Moreover, most of them were coarse-minded men and women, who did little more than bring the sick what they asked for or watch over them when they were dying. And very often these servants lost their lives and their earnings. Since the sick were thus abandoned by neighbours, relatives and friends, while servants were scarce, a habit sprang up which had never been heard of before. Beautiful and noble women , when they fell sick, did not scruple to take a young or old man-servant, whoever he might be, and with no sort of shame, expose every part of their bodies to these men as if they had been women, for they were compelled by the necessity of their sickness to do so. This, perhaps, was a cause of looser morals in those women who survived.

In this way many people died who might have been saved if they had been looked after. Owing to the lack of attendants for the sick and the violence of the plague, such a multitude of people in the city died day and night that it was stupefying to hear of, let alone to see. From sheer necessity, then, several ancient customs were quite altered among the survivors.

. . .

Few were they whose bodies were accompanied to church by more than ten or a dozen neighbours. Nor were these grave and honourable citizens but grave-diggers from the lowest of the people who got themselves called sextons, and performed the task for money. They took up the bier and hurried it off, not to the church chosen by the deceased but to the church nearest, preceded by four or six of the clergy with few candles and often none at all. With the aid of the grave-diggers, the clergy huddled the bodies away in any grave they could find, without giving themselves the trouble of a long or solemn burial service.

The plight of the lower and most of the middle classes was even more pitiful to behold. Most of them remained in their houses, either through poverty or in hopes of safety, and fell sick by thousands. Since they received no care and attention, almost all of them died. Many ended their lives in the streets both at night and during the day; and many others who died in their houses were only known to be dead because the neighbours smelled their decaying bodies. Dead bodies filled every corner. Most of them were treated in the same manner by the survivors, who were more concerned to get rid of their rotting bodies than moved by charity towards the dead. With the aid of porters, if they could get them, they carried the bodies out of the houses and laid them at the doors, where every morning quantities of the dead might be seen. They then were laid on biers or, as these were often lacking, on tables.

Often a single bier carried two or three bodies, and it happened frequently that a husband and wife, two or three brothers, or father and son were taken off on the same bier. It frequently happened that two priests, each carrying a cross, would go out followed by three or four biers carried by porters; and where the priests thought there was one person to bury, there would be six or eight, and often, even more. Nor were these dead honoured by tears and lighted candles and mourners, for things had reached such a pass that people cared no more for dead men than we care for dead goats. . . .

The burial of the victims of the plague in Tournai. Detail of a miniature from "The Chronicles of Gilles Li Muisis" (1272-1352), abbot of the monastery of St. Martin of the Righteous.

"Burying Plague Victims of Tournai" is in the Public Domain

Such was the multitude of corpses brought to the churches every day and almost every hour that there was not enough consecrated ground to give them burial, especially since they wanted to bury each person in the family grave, according to the old custom. Although the cemeteries were full they were forced to dig huge trenches, where they buried the bodies by hundreds. Here they stowed them away like bales in the hold of a ship and covered them with a little earth, until the whole trench was full.

Not to pry any further into all the details of the miseries which afflicted our city, I shall add that the surrounding country was spared nothing of what befell Florence. The villages on a smaller scale were like the city; in the fields and isolated farms the poor wretched peasants and their families were without doctors and any assistance, and perished in the highways, in their fields and houses, night and day, more like beasts than men. Just as the townsmen became dissolute and indifferent to their work and property, so the peasants, when they saw that death was upon them, entirely neglected the future fruits of their past labours both from the earth and from cattle, and thought only of enjoying what they had. Thus it happened that cows, asses, sheep, goats, pigs, fowls and even dogs, those faithful companions of man, left the farms and wandered at their will through the fields, where the wheat crops stood abandoned, unreaped and ungarnered . Many of these animals seemed endowed with reason, for, after they had pastured all day, they returned to the farms for the night of their own free will, without being driven.

Returning from the country to the city, it may be said that such was the cruelty of Heaven, and perhaps in part of men, that between March and July more than one hundred thousand persons died within the walls of Florence, what between the violence of the plague and the abandonment in which the sick were left by the cowardice of the healthy. And before the plague it was not thought that the whole city held so many people.

Oh, what great palaces, how many fair houses and noble dwellings, once filled with attendants and nobles and ladies, were emptied to the meanest servant! How many famous names and vast possessions and renowned estates were left without an heir! How many gallant men and fair ladies and handsome youths, whom Galen, Hippocrates and Aesculapius themselves would have said were in perfect health, at noon dined with their relatives and friends, and at night supped with their ancestors in the next world!

Glossary:

- Aesclepius - a Greek god of healing and medicine who may have been a real person that achieved a mythical reputation.

- bier - a cart or stretcher that is used to transport corpses.

- Hippocrates - an ancient Greek physician, often called the Father of Medicine, who is credited with creating the Hippocratic Oath that American medicine still uses.

- Galen - an ancient Roman physician, surgeon, and medical researcher, particularly in the field of anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology.

- stupefying - having a dazzling or amazing quality.

- superfluidity - being in excess of what is needed or luxurious.

- victuals - food or supplies.

Questions:

- How did the people of Florence react to the onset of the Black Death in their city? How are those reactions similar to, and different from, the reactions of contemporary people to outbreaks like Covid-19?

- What role did economic status play in how the people of Florence responded to the Plague?

- Compare what Boccaccio relates here to what Thucydides and Procopius wrote about in the first two documents.

Sources:

Boccaccio, Giovanni. Decameron of Glovanni Boccaccio . Translated by R. Alelington, Internet Archive, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/dli.venugopal.461/page/n27/mode/2up.

Mark, Joshua J. " Boccaccio on the Black Death: Text & Commentary ." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia , 03 Apr 2020. Web. 20 Apr 2020.

This work (Decameron of Glovanni Boccaccio, by Boccaccio, Giovanni ) is free of known copyright restrictions.