3.5: Focus on Carl Jung (1875–1961) - The Archetypal Collective Unconsciousness

- Page ID

- 14792

Carl Jung, like Lacan, was a disciple of Freud’s, but unlike Lacan, Jung eventually split from Freud, believing that Freud focused too heavily on the importance of sexual desire and the repression that that desire causes. Jung felt that Freud’s theories were, simply, too vague and could be manipulated to fit any scheme. Jung’s complaint seems justified, for Freudian analysis can become reductive as a reader finds phallic symbolism in every knife and fork and yonic symbolism in the soup bowl. Freud’s claim that the unconscious is a result of a person’s repressed desire (which of course is sexual, libidinal), is challenged by Jung, who argues that the mind is constructed of multiple layers of consciousness, the unconscious composing only one of those layers. Jung’s map of the mind is like a house with several stories: on one level lives the conscious, on another the personal unconscious (similar to Freud’s unconscious), on another the collective unconscious, which represents a universal storehouse of images that are common to all humanity. Jung clearly separates himself from Freud, for the collective unconscious is much larger than the unconscious, suggesting that a commonality is shared by all humans—including the importance of myth, ritual, and religion.

The collective unconscious can be accessed through various archetypes that represent for a particular culture a variation of the collective unconscious. Archetypes are like universal Tupperware containers; a particular culture, society, or individual fills that container with its more “personal” symbol-mixture that is molded by the archetype container yet maintains its individual flavor. Thus an archetype is simultaneously universal and particular. Archetypes are those “big dreams” of a culture.

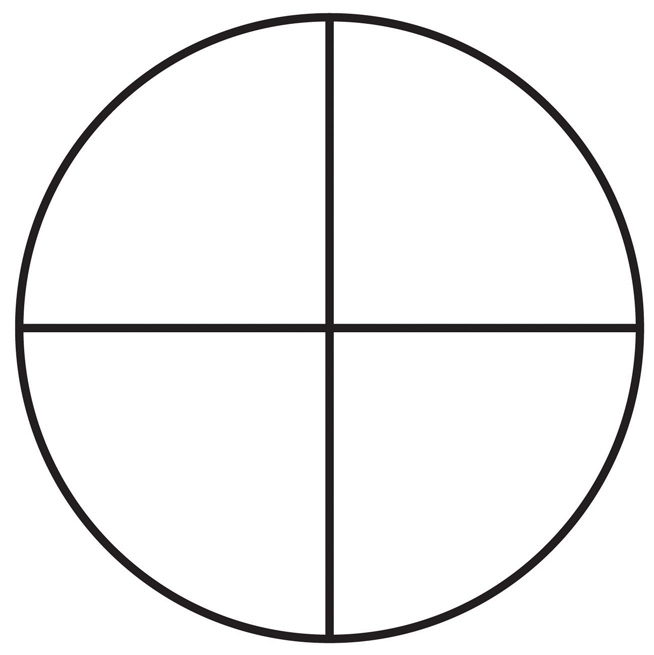

The overriding archetype for Jung is the Self, the image of wholeness or individuation. Jung’s graphic depiction of the Self is the mandala, a circle containing four harmonious parts.

The mandala is beginning and end, perfectly balanced by the four chambers, which composes the unification of the whole Self. Jung’s concept of the collective Self, as you can see, is diametrically opposed to Freud’s and Lacan’s fractured and split individual self. According to Jung each person wears an outward face to the world, a mask or persona, while the inward face contains the shadow and the anima/animus. The shadow is the dark side of the Self that we all hope to hide; it is also the “moral problem” that the Self must grapple with on its way to wholeness. The Self must eventually recognize its shadow as part of its nature. The doppelgänger is the German literary term for the double, and it captures the dark side of the human. Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) is a prototypical story of the double; it focuses on the experiences of the mannered Dr. Henry Jekyll and his alter ego, the beastly Mr. Hyde.Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886; Project Gutenberg, 2011), http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/42/pg42.html. Stevenson’s novel famously suggests that the shadow resides naturally in the Self, though the Self wears a mask to hide that shadow side to the world and to the Self.

Classics Illustrated cover for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1943).

Furthermore, every Self has its own masculine or feminine counterpart to the personality: the animais the female part of the male; the animus is the masculine part of the female. The anima embodies Eros—desire—a maternal archetype that is both positive (the nurturing mother) and negative (the devouring witch). Anima archetypes include the Great Mother, the Tempting Whore, and the Destroying Crone. Conversely, the animus embodies Logos—reason—and is paternal, symbolized by the Great Father, the Wise Old Man, the Lover, and the Destroying Angel archetypes. Both anima and animus have positive and negative dimensions. As the shadow side of the Self is usually hidden or repressed inside, the anima or animus side of the Self is also internalized and hidden, for the Self is unwilling to recognize its feminine or masculine side. That is why the Self will project its opposite onto others, which explains erotic heterosexual love: the male and female are united, finding their anima or animus completed by their partner. Jung falls into the same trap as Freud to a degree—they both make essentialist assumptions about gender.

Since the goal of the Self is harmony, as seen in the mandala, the Self undertakes the archetypal quest to achieve syzygy, the fulfillment of unity, of balance. Jung fathoms that the myths of a culture highlight the Self’s quest for completeness, symbolized by the mandala, and the quaternion Christ is the ideal unified Self, containing Father, Son, Holy Ghost, and Mary (thus balancing the anima and animus). Unlike Freud, who saw no value in religion, Jung’s theory is cemented in religion, with the Self a reflection of God. The quest to find the Self, consequently, is a quest for God within the Self, symbolized by Christ, the purest archetype of the God-in-the-human-self. The quest for the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend, for example, symbolizes search for the unity of Self and God. Such a quest becomes the foundation for a culture’s archetype, this archetype being a variation of the “big dream” of the collective unconscious, the grand archetype.

But how can you apply Jung to literary criticism? In “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry” (1922), Jung explains how literature and the writer operate under the archetype.Carl Jung, “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,” in Twentieth Century Theories of Art, ed. James M. Thompson (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1999), 151–67. Literature is not necessarily based on the personal unconscious of the writer, but on the unconscious mythology that is part of the collective unconsciousness. A writer, then, draws from the collective unconscious for the archetype. Literature is a powerful tool that operates like myth, ritual, and religion.

Other critics have adapted Jungian ideas. Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890–1915), an anthropological compendium of cross-cultural myths, complements Jung’s theories of myth.Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough (1922; Project Gutenberg, 2003), http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3623. Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces(1949) positions Jung in his definition of the monomyth—the departure, initiation, and return of the hero who finds completeness and wholeness during the quest.Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 3rd ed. (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2008). George Lucas, for example, wrote the original Star Wars Trilogy as a modern myth that exemplifies Campbell’s archetypal patterns. Darth Vader, the dark side of the Self, must be confronted, while the need for balance and control and harmony is found in Ben Kenobi’s “force,” which Luke Skywalker must master in order to confront his dark side, his Self, his father.Star Wars Trilogy: Episode IV, A New Hope; Episode V, The Empire Strikes Back; and Episode VI, Return of the Jedi, directed by George Lucas (1980; Beverly Hills, CA: Twentieth Century Fox, 2004), DVD. The most recent example of this myth is seen in Harry Potter’s confrontation with Voldemort.

Jungian criticism is often applied to literature that is considered more mythic—fairy tales, fantasy, and medieval romances. In Fairy Tales: Allegories of Inner Life (1983), J. C. Cooper argues that “Jack and the Beanstalk” depicts common archetypes of the Fool and Trickster, as Jack moves from the fool (for buying “magic” beans) to the trickster (who can outwit the giant).J. C. Cooper, Fairy Tales: Allegories of Inner Life (London: Aquarian, 1983). To Cooper, the fairy tale is about the universal pattern where goodness triumphs over evil, where ingenuity and innocence defeat brutality. Cooper’s reading is far different than Bettelheim’s.

While Jungian criticism is often applied to texts that privilege fantasy over realistic narrative, the theory can find uses in all forms of contemporary literature, as seen in John Neary’s recent Shadows and Illuminations: Literature as Spiritual Journey (2011), in which he examines the work of writers as diverse as Jonathan Safran Foer, Yann Martel, Toni Morrison, to Jane Hamilton.John Neary, Shadows and Illuminations: Literature as Spiritual Journey (Eastbourne, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2011).

Your Process

- What aspect of Jung’s theory most interests you?

- How could you take that interest in Jung and apply it to a work of literature?

- What can you envision as the benefits of such an application?

- Are there any concerns you might have about your approach?