1.6: The Wanderer

- Page ID

- 8155

Author unknown

At least late tenth century, possibly much earlier

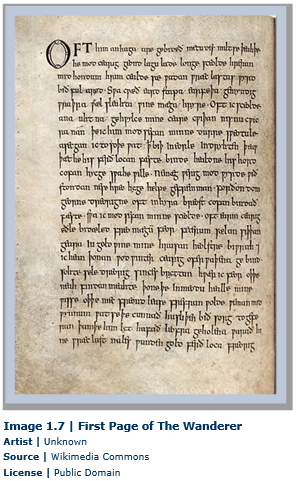

The Wanderer is found only in the manuscript known as the Exeter Book, which was copied in the late tenth century. The 115- line poem follows the usual Anglo- Saxon pattern of short alliterative half-lines separated by a caesura (pause). The wanderer (or “earth- stepper”) has buried his lord (his “gold-friend”) and finds himself alone in the world. Members of a lord’s comitatus, or war band, were expected to die alongside their leader in battle; the wanderer is looking for a new lord as he suffers through the uncertainty, loneliness, and physical hardships of exile. The poem begins and ends with references to Christianity, with a kenning near the end of the poem with God as “Shaper of Men;” the only certainty that the speaker has is that there is a “safe home” waiting for him in heaven. The rest of the poem focuses on what he has lost. Like The Ruin and The Seafarer, also found in the Exeter Book, The Wanderer is what is known as an “ubi sunt” poem (Latin for “where has”). In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Two Towers, Aragorn recites a poem about Eorl the Young that begins “Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?” (142; the movie transfers the speech to King Theoden), which was drawn directly from The Wanderer’s “Where has the horse gone? Where is the man?” Because of its theme, The Wanderer is usually classified as a type of elegy, or lament for what has been lost.

1.7.1 Bibliography

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Two Towers. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Directed by Peter Jackson. New Line Cinema and Wingnut Films. 2002.

1.7.2 The Wanderer

Often the solitary man prays for favour, for the mercy of the Lord, though, sad at heart, he must needs stir with his bands for a weary while the icy sea across the watery ways, must journey the paths of exile; settled in truth is fate! So spoke the wanderer, mindful of hardships, of cruel slaughters, of the fall of kinsmen:

’Often I must bewail my sorrows in my loneliness at the dawn of each day; there is none of living men now to whom I dare speak my heart openly. I know for a truth that it is a noble custom for a man to bind fast the thoughts of his heart, to treasure his broodings, let him think as he will. Nor can the weary in mood resist fate, nor does the fierce thought avail anything. Wherefore those eager for glory often bind fast in their secret hearts a sad thought. So I, sundered from my native land, far from noble kinsmen, often sad at heart, had to fetter my mind, when in years gone by the darkness of the earth covered my gold-friend, and I went thence in wretchedness with wintry care upon me over the frozen waves, gloomily sought the hall of a treasure-giver wherever I could find him far or near, who might know me in the mead hall or comfort me, left without friends, treat me with kindness. He knows who puts it to the test how cruel a comrade is sorrow for him who has few dear protectors; his is the path of exile, in no wise the twisted gold; a chill body, in no wise the riches of the earth; he thinks of retainers in hall and the receiving of treasure, of how in his youth his gold-friend was kind to him at the feast. The joy has all perished. Wherefore he knows this who must long forgo the counsels of his dear lord and friend, when sorrow and sleep together often bind the poor solitary man; it seems to him in his mind that he clasps and kisses his lord and lays hands and head on his knee, as when erstwhile in past days he was near the gift-throne; then the friendless man wakes again, sees before him the dark waves, the sea-birds bathing, spreading their feathers; frost and snow falling mingled with hail. Then heavier are the wounds in his heart, sore for his beloved; sorrow is renewed. Then the memory of kinsmen crosses his mind; he greets them with songs; he gazes on them eagerly. The companions of warriors swim away again; the souls of sailors bring there not many known songs. Care is renewed in him who must needs send very often his weary mind over the frozen waves. And thus I cannot think why in this world my mind becomes not overcast when I consider all the life of earls, how of a sudden they have given up hall, courageous retainers. So this world each day passes and falls; for a man cannot become wise till he has his share of years in the world. A wise man must be patient, not over-passionate, nor over-hasty of speech, nor over-weak or rash in war, nor over-fearful, nor over-glad, nor over-covetous, never over-eager to boast ere he has full knowledge.) A man must bide his time, when he boasts in his speech, until he knows well in his pride whither the thoughts of the mind will turn. A wise man must see how dreary it will be when all the riches of this world stand waste, as in different places throughout this world walls stand, blown upon by winds, hung with frost, the dwellings in ruins. The wine halls crumble; the rulers lie low, bereft of joy; the mighty warriors have all fallen in their pride by the wall; war carried off some, bore them on far paths; one the raven bore away over the high sea; one the grey wolf gave over to death; one an earl with sad face hid in the earth-cave. Thus did the Creator of men lay waste this earth till the old work of giants stood empty, free from the revel of castle-dwellers. Then he who has thought wisely of the foundation of things and who deeply ponders this dark life, wise in his heart, often turns his thoughts to the many slaughters of the past, and speaks these words:

‘“Whither has gone the horse? Whither has gone the man? Whither has gone the giver of treasure? Whither has gone the place of feasting? Where are the joys of hall? Alas, the bright cup! Alas, the warrior in his corslet! Alas, the glory of the prince! How that time has passed away, has grown dark under the shadow of night, as if it had never been! Now in the place of the dear warriors stands a wall, wondrous high, covered with serpent shapes; the might of the ash-wood spears has carried off the earls, the weapon greedy for slaughter—a glorious fate; and storms beat upon these rocky slopes; the falling storm binds the earth, the terror of winter. Then comes darkness, the night shadow casts gloom, sends from the north fierce hailstorms to the terror of men. Everything is full of hardship in the kingdom of earth; the decree of fate changes the world under the heavens. Here possessions are transient, here friends are transient, here man is transient, here woman is transient; all this firm-set earth becomes empty.”’

So spoke the wise man in his heart, and sat apart in thought. Good is he who holds his faith; nor shall a man ever show forth too quickly the sorrow of his breast, except he, the earl, first know how to work its cure bravely. Well is it for him who seeks mercy, comfort from the Father in heaven, where for us all security stands.

1.7.3 Reading and Review Questions

- What are all of the kennings in the poem, and what do they mean?

- Where is the wanderer? Is there any symbolic meaning in the setting of the poem?

- Do the last lines, with their focus on Christianity, fit with the rest of the poem? Why or why not?

- What makes a man wise, according to the poem? How is it an Anglo- Saxon perspective on wisdom, or is it?

- How much does shame play a role in the wanderer’s perspectives? Should he feel shame, in either an Anglo-Saxon or a Christian context?