2.11: Dante Gabriel Rosetti (1828-1882)

- Page ID

- 41784

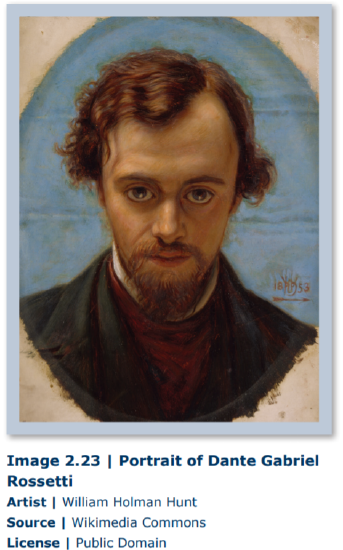

D. G. Rossetti was born into an intellectual family; his father was a Dante scholar, and his mother, a trained governess. D. G. Rossetti trained as both a painter and poet, studying painting with Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), the father of novelist Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939). He and fellow artists founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, and Rossetti published several of his poems in its journal The Germ (1850).

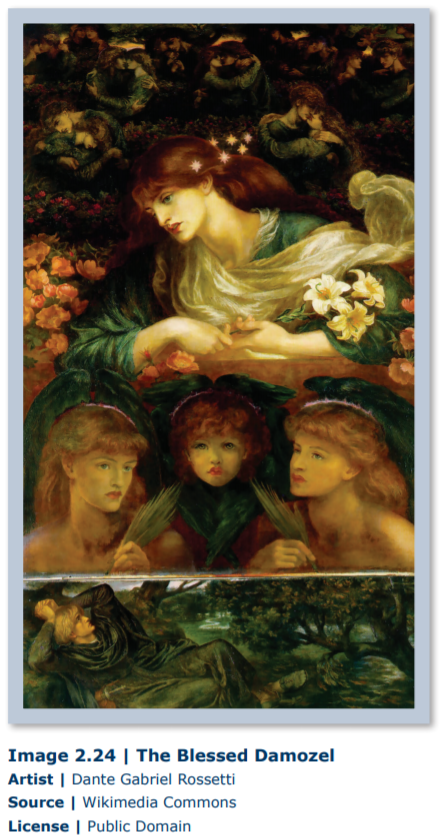

Artistic rebels, the Pre-Raphaelites stood for the artist’s vision of the truth regardless of convention. They countered the industrialization and mechanization of their era with an organicism they found in the Medieval era. They also sought fidelity to the visible world, often achieved through scrupulously-rendered minute detail. Their elaborate, realistic details were faithful to nature but also symbolic. Rossetti in particular made the non-visual—the spirit or details of religious myth—visible.

Rossetti married poet and painter Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862), who was also his model. After losing a child, she committed suicide. Out of remorse, Rossetti buried a manuscript of his poems in her grave. Later, he had her body exhumed to recover his poems. Rossetti’s reputation grew, and he was embraced by a second generation of Pre-Raphaelites—calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—particularly by William Morris, one of the most important figures in this second group.

The real love of Rossetti’s life was Jane Burden (1839-1914) who married Morris. Rossetti and Morris cofounded a firm of designers that responded to Ruskin’s adjuration to  involve the whole human being in their work. Rossetti and Jane Morris conducted an affair—that was neither sanctioned nor condemned by Morris. Rossetti wrote his important sonnet sequence, House of Life, influenced by his love for Jane Morris. His poetry was brutally attacked by Robert Buchanan (1841- 1901), who described Rossetti’s poetry as “fleshly”—a far from complimentary term during the Victorian era.

involve the whole human being in their work. Rossetti and Jane Morris conducted an affair—that was neither sanctioned nor condemned by Morris. Rossetti wrote his important sonnet sequence, House of Life, influenced by his love for Jane Morris. His poetry was brutally attacked by Robert Buchanan (1841- 1901), who described Rossetti’s poetry as “fleshly”—a far from complimentary term during the Victorian era.

Rossetti, who was already addicted to chloral, suffered a nervous breakdown and a decline in his health. He managed to continue to write and paint until he died suddenly in 1882, leaving unfinished paintings behind.

2.11.1: “The Blessed Damozel”

THE blessed damozel leaned out

From the gold bar of Heaven;

Her eyes were deeper than the depth

Of waters stilled at even;

She had three lilies in her hand,

And the stars in her hair were seven.

Her robe, ungirt from clasp to hem,

Her robe, ungirt from clasp to hem,

No wrought flowers did adorn,

But a white rose of Mary’s gift,

For service meetly worn;

Her hair that lay along her back

Was yellow like ripe corn.

Herseemed she scarce had been a day

One of God’s choristers;

The wonder was not yet quite gone

From that still look of hers;

Albeit, to them she left, her day

Had counted as ten years.

(To one, it is ten years of years. . . .

Yet, now, and in this place,

Surely she leaned o’er me—her hair

Fell all about my face. . . .

Nothing: the autumn-fall of leaves.

The whole year sets apace.)

It was the rampart of God’s house

That she was standing on;

By God built over the sheer depth

The which is Space begun;

So high, that looking downward thence

She scarce could see the sun.

It lies in Heaven, across the flood

Of ether, as a bridge.

Beneath, the tides of day and night

With flame and darkness ridge

The void, as low as where this earth

Spins like a fretful midge.

Around her, lovers, newly met

‘Mid deathless love’s acclaims,

Spoke evermore among themselves

Their heart-remembered names;

And the souls mounting up to God

Went by her like thin flames.

And still she bowed herself and stooped

Out of the circling charm;

Until her bosom must have made

The bar she leaned on warm,

And the lilies lay as if asleep

Along her bended arm.

From the fixed place of Heaven she saw

Time like a pulse shake fierce

Through all the worlds. Her gaze still strove

Within the gulf to pierce

Its path; and now she spoke as when

The stars sang in their spheres.

The sun was gone now; the curled moon.

Was like a little feather

Fluttering far down the gulf; and now

She spoke through the still weather.

Her voice was like the voice of stars

Had when they sang together.

(Ah sweet! Even now, in that bird’s song,

Strove not her accents there,

Fain to be hearkened? When those bells

Possessed the mid-day air,

Strove not her steps to reach my side

Down all the echoing stair?) “I wish that he were come to me,

For he will come,” she said.

“Have I not prayed in Heaven?—on earth,

Lord, Lord, has he not pray’d?

Are not two prayers a perfect strength?

And shall I feel afraid?

“When round his head the aureole clings,

And he is clothed in white,

I’ll take his hand and go with him

To the deep wells of light;

As unto a stream we will step down,

And bathe there in God’s sight.

“We two will stand beside that shrine,

Occult, withheld, untrod,

Whose lamps are stirred continually

With prayer sent up to God;

And see our old prayers, granted, melt

Each like a little cloud.

“We two will lie i’ the shadow of

That living mystic tree

Within whose secret growth the Dove

Is sometimes felt to be,

While every leaf that His plumes touch

Saith His Name audibly.

“And I myself will teach to him,

I myself, lying so,

The songs I sing here; which his voice

Shall pause in, hushed and slow,

And find some knowledge at each pause,

Or some new thing to know.”

(Alas! we two, we two, thou say’st!

Yea, one wast thou with me

That once of old. But shall God lift

To endless unity

The soul whose likeness with thy soul

Was but its love for thee?)

“We two,” she said, “will seek the groves

Where the lady Mary is,

With her five handmaidens, whose names

Are five sweet symphonies,

Cecily, Gertrude, Magdalen,

Margaret and Rosalys.

“Circlewise sit they, with bound locks

And foreheads garlanded;

Into the fine cloth white like flame

Weaving the golden thread,

To fashion the birth-robes for them

Who are just born, being dead.

“He shall fear, haply, and be dumb:

Then will I lay my cheek

To his, and tell about our love,

Not once abashed or weak:

And the dear Mother will approve

My pride, and let me speak.

“Herself shall bring us, hand in hand,

To Him round whom all souls

Kneel, the clear-ranged unnumbered heads

Bowed with their aureoles:

And angels meeting us shall sing

To their citherns and citoles.

“There will I ask of Christ the Lord

Thus much for him and me:—

Only to live as once on earth

With Love,—only to be,

As then awhile, for ever now

Together, I and he.”

She gazed and listened and then said,

Less sad of speech than mild,—

“All this is when he comes.” She ceased.

The light thrilled towards her, fill’d

With angels in strong level flight.

Her eyes prayed, and she smil’d.

(I saw her smile.) But soon their path

Was vague in distant spheres:

And then she cast her arms along

The golden barriers,

And laid her face between her hands,

And wept. (I heard her tears.)

2.11.2: “My Sister’s Sleep”

She fell asleep on Christmas Eve.

At length the long-ungranted shade.

Of weary eyelids overweighed

The pain nought else might yet relieve.

Our mother, who had leaned all day

Over the bed from chime to chime,

Then raised herself for the first time,

And as she sat her down did pray.

Her little worktable was spread

With work to finish. For the glare

Made by her candle, she had care

To work some distance from the bed.

Without, there was a cold moon up,

Of winter radiance sheer and thin;

The hollow halo it was in

Was like an icy crystal cup.

Through the small room, with subtle sound

Of flame, by vents the fireshine drove

And reddened. In its dim alcove

The mirror shed a clearness round.

I had been sitting up some nights,

And my tired mind felt weak and blank;

Like a sharp strengthening wine it drank

The stillness and the broken lights.

Twelve struck. That sound, by dwindling years

Heard in each hour, crept off; and then

The ruffled silence spread again,

Like water that a pebble stirs.

Our mother rose from where she sat;

Her needles, as she laid them down,

Met lightly, and her silken gown

Settled—no other noise than that.

“Glory unto the Newly Born!”

So, as said angels, she did say,

Because we were in Christmas Day.

Though it would still be long till morn.

Just then in the room over us

There was a pushing back of chairs

As some who had sat unawares

So late, now heard the hour, and rose.

With anxious softly-stepping haste

Our mother went where Margaret lay,

Fearing the sounds o’erhead—should they

Have broken her long watched-for rest!

She stooped an instant, calm, and turned,

But suddenly turned back again;

And all her features seemed in pain

With woe, and her eyes gazed and yearned.

For my part, I but hid my face,

And held my breath, and spoke no word.

There was none spoken; but I heard

The silence for a little space.

Our mother bowed herself and wept;

And both my arms fell, and I sad,

“God knows I knew that she was dead.”

And there, all white, my sister slept.

Then kneeling, upon Christmas morn

A little after twelve o’clock,

We said, ere the first quarter struck,

“Christ’s blessing on the newly born!”

2.11.3: “The Burden of Nineveh”

IN our Museum galleries

To-day I lingered o’er the prize

Dead Greece vouchsafes to living eyes,—

Her Art forever in fresh wise

From hour to hour rejoicing me.

Sighing I turned at last to win

Once more the London dirt and din;

And as I made the swing-door spin

And issued, they were hoisting in

A wingèd beast from Nineveh.

A human face the creature wore,

And hoofs behind and hoofs before,

And flanks with dark runes fretted o’er.

’T was bull, ’t was mitred Minotaur,

A dead disbowelled mystery;

The mummy of a buried faith

Stark from the charnel without scathe,

Its wings stood for the light to bathe,—

Such fossil cerements as might swathe

The very corpse of Nineveh.

The print of its first rush-wrapping,

Wound ere it dried, still ribbed the thing.

What song did the brown maidens sing,

From purple mouths alternating,

When that was woven languidly?

What vows, what rites, what prayers preferred,

What songs has the strange image heard?

In what blind vigil stood interred

For ages, till an English word

Broke silence first at Nineveh?

Oh, when upon each sculptured court,

Where even the wind might not resort,—

O’er which Time passed, of like import

With the wild Arab boys at sport,—

A living face looked in to see:

Oh, seemed it not—the spell once broke—

As though the carven warriors woke,

As though the shaft the string forsook,

The cymbals clashed, the chariots shook,

And there was life in Nineveh?

On London stones our sun anew

The beast’s recovered shadow threw.

(No shade that plague of darkness knew,

No light, no shade, while older grew

By ages the old earth and sea.)

Lo thou! could all thy priests have shown

Such proof to make thy godhead known?

From their dead Past thou liv’st alone;

And still thy shadow is thine own

Even as of yore in Nineveh.

That day whereof we keep record,

When near thy city-gates the Lord

Sheltered his Jonah with a gourd,

This sun (I said), here present, poured

Even thus this shadow that I see.

This shadow has been shed the same

From sun and moon,—from lamps which came

For prayer,—from fifteen days of flame,

The last, while smouldered to a name

Sardanapalus’ Nineveh.

Within thy shadow, haply, once

Sennacherib has knelt, whose sons

Smote him between the altar-stones;

Or pale Semiramis her zones

Of gold, her incense brought to thee,

In love for grace, in war for aid:….

Ay, and who else?…. till ’neath thy shade

Within his trenches newly made

Last year the Christian knelt and prayed—

Not to thy strength—in Nineveh.

Now, thou poor god, within this hall

Where the blank windows blind the wall

From pedestal to pedestal,

The kind of light shall on thee fall

Which London takes the day to be:

While school-foundations in the act

Of holiday, three files compact,

Shall learn to view thee as a fact

Connected with that zealous tract:

“Rome,—Babylon and Nineveh.”

Deemed they of this, those worshippers,

When, in some mythic chain of verse

Which man shall not again rehearse, The faces of thy ministers

Yearned pale with bitter ecstasy?

Greece, Egypt, Rome,—did any god

Before whose feet men knelt unshod

Deem that in this unblest abode

Another scarce more unknown god

Should house with him, from Nineveh?

Ah! in what quarries lay the stone

From which this pygmy pile has grown,

Unto man’s need how long unknown,

Since thy vast temples, court and cone,

Rose far in desert history?

Ah! what is here that does not lie

All strange to thine awakened eye?

Ah! what is here can testify

(Save that dumb presence of the sky)

Unto thy day and Nineveh?

Why, of those mummies in the room

Above, there might indeed have come

One out of Egypt to thy home,

An alien. Nay, but were not some

Of these thine own “antiquity”?

And now,—they and their gods and thou

All relics here together,—now

Whose profit? whether bull or cow,

Isis or Ibis, who or how,

Whether of Thebes or Nineveh?

The consecrated metals found,

And ivory tablets underground,

Winged seraphim and creatures crowned,

When air and daylight filled the mound,

Fell into dust immediately.

And even as these, the images

Of awe and worship,—even as these,—

So, smitten with the sun’s increase,

Her glory mouldered and did cease

From immemorial Nineveh.

The day her builders made their halt,

Those cities of the lake of salt

Stood firmly ’stablished without fault,

Made proud with pillars of basalt,

With sardonyx and porphyry.

The day that Jonah bore abroad

To Nineveh the voice of God,

A brackish lake lay in his road,

Where erst Pride fixed her sure abode,

As then in royal Nineveh.

The day when he, Pride’s lord and Man’s,

Showed all the kingdoms at a glance

To Him before whose countenance

The years recede, the years advance,

And said, Fall down and worship me—

Mid all the pomp beneath that look,

Then stirred there, haply, some rebuke,

Where to the wind the salt pools shook,

And in those tracts, of life forsook,

That knew thee not, O Nineveh!

Delicate harlot! On thy throne

Thou with a world beneath thee prone

In state for ages sat’st alone;

And needs were years and lustres flown

Ere strength of man could vanquish thee:

Whom even thy victor foes must bring,

Still royal, among maids that sing

As with doves’ voices, taboring

Upon their breasts, unto the King,—

A kingly conquest, Nineveh!

Here woke my thought.

The wind’s slow sway

Had waxed; and like the human play

Of scorn that smiling spreads away,

The sunshine shivered off the day:

The callous wind, it seemed to me,

Swept up the shadow from the ground:

And pale as whom the Fates astound,

The god forlorn stood winged and crowned:

Within I knew the cry lay bound

Of the dumb soul of Nineveh.

And as I turned, my sense half shut

Still saw the crowds of kerb and rut

Go past as marshalled to the strut

Of rank in gypsum quaintly cut.

It seemed in one same pageantry

They followed forms which had been erst;

To pass, till on my sight should burst

That future of the best or worst

When some may question which was first,

Of London or of Nineveh.

For as that Bull-god once did stand

And watched the burial-clouds of sand,

Till these at last without a hand

Rose o’er his eyes, another land,

And blinded him with destiny:—

So may he stand again; till now,

In ships of unknown sail and prow,

Some tribe of the Australian plough

Bear him afar,—a relic now

Of London, not of Nineveh!

Or it may chance indeed that when

Man’s age is hoary among men,—

His centuries threescore and ten,—

His furthest childhood shall seem then

More clear than later times may be:

Who, finding in this desert place

This form, shall hold us for some race

That walked not in Christ’s lowly ways,

But bowed its pride and vowed its praise

Unto the God of Nineveh.

The smile rose first,—anon drew nigh

The thought: Those heavy wings spread high

So sure of flight, which do not fly;

That set gaze never on the sky;

Those scriptured flanks it cannot see;

Its crown a brow-contracting load:

Its planted feet which trust the sod

(So grew the image as I trod):

O Nineveh, was this thy God,—

Thine also, mighty Nineveh?

2.11.4: “Jenny”

“Vengeance of Jenny’s case! Fie on her! Never name her, child!”

— (Mrs. Quickly.)

Lazy laughing languid Jenny,

Fond of a kiss and fond of a guinea,

Whose head upon my knee to-night

Rests for a while, as if grown light

With all our dances and the sound

To which the wild tunes spun you round:

Fair Jenny mine, the thoughtless queen

Of kisses which the blush between

Could hardly make much daintier;

Whose eyes are as blue skies, whose hair

Is countless gold incomparable:

Fresh flower, scarce touched with signs that tell

Of Love’s exuberant hotbed:—Nay,

Poor flower left torn since yesterday

Until to-morrow leave you bare;

Poor handful of bright spring-water

Flung in the whirlpool’s shrieking face;

Poor shameful Jenny, full of grace

Thus with your head upon my knee;—

Whose person or whose purse may be

The lodestar of your reverie?

This room of yours, my Jenny, looks

A change from mine so full of books,

Whose serried ranks hold fast, forsooth,

So many captive hours of youth,—

The hours they thieve from day and night

To make one’s cherished work come right,

And leave it wrong for all their theft,

Even as to-night my work was left:

Until I vowed that since my brain

And eyes of dancing seemed so fain,

My feet should have some dancing too:—

And thus it was I met with you.

Well, I suppose ‘twas hard to part,

For here I am. And now, sweetheart,

You seem too tired to get to bed.

It was a careless life I led

When rooms like this were scarce so strange

Not long ago. What breeds the change,—

The many aims or the few years?

Because to-night it all appears

Something I do not know again.

The cloud’s not danced out of my brain,—

The cloud that made it turn and swim

While hour by hour the books grew dim.

Why, Jenny, as I watch you there,—

For all your wealth of loosened hair,

Your silk ungirdled and unlac’d

And warm sweets open to the waist,

All golden in the lamplight’s gleam,—

You know not what a book you seem,

Half-read by lightning in a dream!

How should you know, my Jenny?

Nay, And I should be ashamed to say:—

Poor beauty, so well worth a kiss!

But while my thought runs on like this

With wasteful whims more than enough,

I wonder what you’re thinking of.

If of myself you think at all,

What is the thought?—conjectural

On sorry matters best unsolved?—

Or inly is each grace revolved

To fit me with a lure?—or (sad

To think!) perhaps you’re merely glad

That I’m not drunk or ruffianly

And let you rest upon my knee.

For sometimes, were the truth confess’d,

You’re thankful for a little rest,—

Glad from the crush to rest within,

From the heart-sickness and the din

Where envy’s voice at virtue’s pitch

Mocks you because your gown is rich;

And from the pale girl’s dumb rebuke,

Whose ill-clad grace and toil-worn look

Proclaim the strength that keeps her weak

And other nights than yours bespeak;

And from the wise unchildish elf,

To schoolmate lesser than himself

Pointing you out, what thing you are:—

Yes, from the daily jeer and jar,

From shame and shame’s outbraving too,

Is rest not sometimes sweet to you?—

But most from the hatefulness of man

Who spares not to end what he began,

Whose acts are ill and his speech ill,

Who, having used you at his will,

Thrusts you aside, as when I dine

I serve the dishes and the wine.'

Well, handsome Jenny mine, sit up,

I’ve filled our glasses, let us sup,

And do not let me think of you,

Lest shame of yours suffice for two.

What, still so tired? Well, well then, keep

Your head there, so you do not sleep;

But that the weariness may pass

And leave you merry, take this glass.

Ah! lazy lily hand, more bless’d

If ne’er in rings it had been dress’d

Nor ever by a glove conceal’d!

Behold the lilies of the field,

They toil not neither do they spin;

(So doth the ancient text begin,—

Not of such rest as one of these

Can share.) Another rest and ease

Along each summer-sated path

From its new lord the garden hath,

Than that whose spring in blessings ran

Which praised the bounteous husbandman,

Ere yet, in days of hankering breath,

The lilies sickened unto death.

What, Jenny, are your lilies dead?

Aye, and the snow-white leaves are spread

Like winter on the garden-bed.

But you had roses left in May,—

They were not gone too. Jenny, nay,

But must your roses die, and those

Their purfled buds that should unclose?

Even so; the leaves are curled apart,

Still red as from the broken heart,

And here’s the naked stem of thorns.

Nay, nay, mere words. Here nothing warns

As yet of winter. Sickness here

Or want alone could waken fear,—

Nothing but passion wrings a tear.

Except when there may rise unsought

Haply at times a passing thought

Of the old days which seem to be

Much older than any history

That is written in any book;

When she would lie in fields and look

Along the ground through the blown grass,

And wonder where the city was,

Far out of sight, whose broil and bale

They told her then for a child’s tale.

Jenny, you know the city now.

A child can tell the tale there, how

Some things which are not yet enroll’d

In market-lists are bought and sold

Even till the early Sunday light,

When Saturday night is market-night

Everywhere, be it dry or wet,

And market-night in the Haymarket.

Our learned London children know,

Poor Jenny, all your pride and woe;

Have seen your lifted silken skirt

Advertise dainties through the dirt;

Have seen your coach-wheels splash rebuke

On virtue; and have learned your look

When, wealth and health slipped past, you stare

Along the streets alone, and there,

Round the long park, across the bridge,

The cold lamps at the pavement’s edge

Wind on together and apart,

A fiery serpent for your heart.

Let the thoughts pass, an empty cloud!

Suppose I were to think aloud,—

What if to her all this were said?

Why, as a volume seldom read

Being opened halfway shuts again,

So might the pages of her brain

Be parted at such words, and thence

Close back upon the dusty sense.

For is there hue or shape defin’d

In Jenny’s desecrated mind,

Where all contagious currents meet,

A Lethe of the middle street?

Nay, it reflects not any face,

Nor sound is in its sluggish pace,

But as they coil those eddies clot,

And night and day remember not.

Why, Jenny, you’re asleep at last!—

Asleep, poor Jenny, hard and fast,—

So young and soft and tired; so fair,

With chin thus nestled in your hair,

Mouth quiet, eyelids almost blue

As if some sky of dreams shone through!

Just as another woman sleeps!

Enough to throw one’s thoughts in heaps

Of doubt and horror,—what to say

Or think,—this awful secret sway,

The potter’s power over the clay!

Of the same lump (it has been said)

For honour and dishonour made,

Two sister vessels. Here is one.

My cousin Nell is fond of fun,

And fond of dress, and change, and praise,

So mere a woman in her ways:

And if her sweet eyes rich in youth

Are like her lips that tell the truth,

My cousin Nell is fond of love.

And she’s the girl I’m proudest of.

Who does not prize her, guard her well?

The love of change, in cousin Nell,

Shall find the best and hold it dear:

The unconquered mirth turn quieter

Not through her own, through others’ woe:

The conscious pride of beauty glow

Beside another’s pride in her,

One little part of all they share.

For Love himself shall ripen these

In a kind soil to just increase

Through years of fertilizing peace.

Of the same lump (as it is said)

For honour and dishonour made,

Two sister vessels. Here is one.

It makes a goblin of the sun.

So pure,—so fall’n! How dare to think

Of the first common kindred link?

Yet, Jenny, till the world shall burn

It seems that all things take their turn;

And who shall say but this fair tree

May need, in changes that may be,

Your children’s children’s charity?

Scorned then, no doubt, as you are scorn’d!

Shall no man hold his pride forewarn’d

Till in the end, the Day of Days,

At Judgment, one of his own race,

As frail and lost as you, shall rise,—

His daughter, with his mother’s eyes?

How Jenny’s clock ticks on the shelf!

Might not the dial scorn itself

That has such hours to register?

Yet as to me, even so to her

Are golden sun and silver moon,

In daily largesse of earth’s boon,

Counted for life-coins to one tune.

And if, as blindfold fates are toss’d,

Through some one man this life be lost,

Shall soul not somehow pay for soul?

Fair shines the gilded aureole

In which our highest painters place

Some living woman’s simple face.

And the stilled features thus descried

As Jenny’s long throat droops aside,—

The shadows where the cheeks are thin,

And pure wide curve from ear to chin,—

With Raffael’s, Leonardo’s hand

To show them to men’s souls, might stand,

Whole ages long, the whole world through,

For preachings of what God can do.

What has man done here? How atone,

Great God, for this which man has done?

And for the body and soul which by

Man’s pitiless doom must now comply

With lifelong hell, what lullaby

Of sweet forgetful second birth

Remains? All dark. No sign on earth

What measure of God’s rest endows

The many mansions of his house.

If but a woman’s heart might see

Such erring heart unerringly

For once! But that can never be.

Like a rose shut in a book

In which pure women may not look,

For its base pages claim control

To crush the flower within the soul;

Where through each dead rose-leaf that clings,

Pale as transparent psyche-wings,

To the vile text, are traced such things

As might make lady’s cheek indeed

More than a living rose to read;

So nought save foolish foulness may

Watch with hard eyes the sure decay;

And so the life-blood of this rose,

Puddled with shameful knowledge, flows

Through leaves no chaste hand may unclose:

Yet still it keeps such faded show

Of when ‘twas gathered long ago,

That the crushed petals’ lovely grain,

The sweetness of the sanguine stain,

Seen of a woman’s eyes, must make

Her pitiful heart, so prone to ache,

Love roses better for its sake:—

Only that this can never be:—

Even so unto her sex is she.

Yet, Jenny, looking long at you,

The woman almost fades from view.

A cipher of man’s changeless sum

Of lust, past, present, and to come,

Is left. A riddle that one shrinks

To challenge from the scornful sphinx.

Like a toad within a stone

Seated while Time crumbles on;

Which sits there since the earth was curs’d

For Man’s transgression at the first;

Which, living through all centuries,

Not once has seen the sun arise;

Whose life, to its cold circle charmed,

The earth’s whole summers have not warmed;

Which always—whitherso the stone

Be flung—sits there, deaf, blind, alone;—

Aye, and shall not be driven out

Till that which shuts him round about

Break at the very Master’s stroke,

And the dust thereof vanish as smoke,

And the seed of Man vanish as dust:—

Even so within this world is Lust.

Come, come, what use in thoughts like this?

Poor little Jenny, good to kiss,—

You’d not believe by what strange roads

Thought travels, when your beauty goads

A man to-night to think of toads!

Jenny, wake up . . . . Why, there’s the dawn!

And there’s an early waggon drawn

To market, and some sheep that jog

Bleating before a barking dog;

And the old streets come peering through

Another night that London knew;

And all as ghostlike as the lamps.

So on the wings of day decamps

My last night’s frolic. Glooms begin

To shiver off as lights creep in

Past the gauze curtains half drawn-to,

And the lamp’s doubled shade grows blue,—

Your lamp, my Jenny, kept alight,

Like a wise virgin’s, all one night!

And in the alcove coolly spread

Glimmers with dawn your empty bed;

And yonder your fair face I see

Reflected lying on my knee,

Where teems with first foreshadowings

Your pier-glass scrawled with diamond rings

And on your bosom all night worn

Yesterday’s rose now droops forlorn

But dies not yet this summer morn.

And now without, as if some word

Had called upon them that they heard,

The London sparrows far and nigh

Clamour together suddenly;

And Jenny’s cage-bird grown awake

Here in their song his part must take,

Because here too the day doth break.

And somehow in myself the dawn

Among stirred clouds and veils withdrawn

Strikes greyly on her. Let her sleep.

But will it wake her if I heap

These cushions thus beneath her head

Where my knee was? No,—there’s your bed,

My Jenny, while you dream.

And there I lay among your golden hair

Perhaps the subject of your dreams,

These golden coins.

For still one deems

That Jenny’s flattering sleep confers

New magic on the magic purse,—

Grim web, how clogged with shrivelled flies!

Between the threads fine fumes arise

And shape their pictures in the brain.

There roll no streets in glare and rain,

Nor flagrant man-swine whets his tusk;

But delicately sighs in musk

The homage of the dim boudoir;

Or like a palpitating star

Thrilled into song, the opera-night

Breathes faint in the quick pulse of light;

Or at the carriage-window shine

Rich wares for choice; or, free to dine,

Whirls through its hour of health (divine

For her) the concourse of the Park.

And though in the discounted dark

Her functions there and here are one,

Beneath the lamps and in the sun

There reigns at least the acknowledged belle

Apparelled beyond parallel.

Ah Jenny, yes, we know your dreams.

For even the Paphian Venus seems

A goddess o’er the realms of love,

When silver-shrined in shadowy grove:

Aye, or let offerings nicely plac’d

But hide Priapus to the waist,

And whoso looks on him shall see

An eligible deity.

Why, Jenny, waking here alone

May help you to remember one,

Though all the memory’s long outworn

Of many a double-pillowed morn.

I think I see you when you wake,

And rub your eyes for me, and shake

My gold, in rising, from your hair,

A Danaë for a moment there.

Jenny, my love rang true! for still

Love at first sight is vague, until

That tinkling makes him audible.

And must I mock you to the last,

Ashamed of my own shame,—aghast

Because some thoughts not born amiss

Rose at a poor fair face like this?

Well, of such thoughts so much I know:

In my life, as in hers, they show,

By a far gleam which I may near,

A dark path I can strive to clear.

Only one kiss. Goodbye, my dear.

2.11.5: “The Woodspurge”

The wind flapped loose, the wind was still,

Shaken out dead from tree and hill:

I had walked on at the wind’s will,—

I sat now, for the wind was still.

Between my knees my forehead was,—

My lips, drawn in, said not Alas!

My hair was over in the grass,

My naked ears heard the day pass.

My eyes, wide open, had the run

Of some ten weeds to fix upon;

Among those few, out of the sun,

The woodspurge flowered, three cups in one.

From perfect grief there need not be

Wisdom or even memory:

One thing then learnt remains to me,—

The woodspurge has a cup of three.

2.11.6: From The House of Life

2.11.6.1: “The Sonnet”

A Sonnet is a moment’s monument,

Memorial from the Soul’s eternity

To one dead deathless hour. Look that it be,

Whether for lustral rite or dire portent,

Of its own arduous fulness reverent:

Carve it in ivory or in ebony,

As Day or Night may rule; and let Time see

Its Powering crest impearled and orient.

A Sonnet is a coin: its face reveals

The soul,—its converse, to what Power ‘tis due:—

Whether for tribute to the august appeals

Of Life, or dower in Love’s high retinue,

It serve, or, ‘mid the dark wharf’s cavernous breath,

In Charon’s palm it pay the toll to Death.

2.11.6.2: “19. Silent Noon”

Your hands lie open in the long fresh grass,—

The finger-points look through like rosy blooms:

Your eyes smile peace. The pasture gleams and glooms

‘Neath billowing skies that scatter and amass.

All round our nest, far as the eye can pass,

Are golden kingcup-fields with silver edge

Where the cow-parsley skirts the hawthorn-hedge.

‘Tis visible silence, still as the hour-glass.

Deep in the sun-searched growths the dragon-fly

Hangs like a blue thread loosened from the sky:—

So this wing’d hour is dropt to us from above.

Oh! clasp we to our hearts, for deathless dower,

This close-companioned inarticulate hour

When twofold silence was the song of love.

2.11.7: Reading and Review Questions

- What, if anything, is revolutionary about Rossetti’s depiction of heaven, the soul, and earth?

- To what extent, if any, might the sonnets in The House of Life be characterized as Romantic rather than Medieval? And to what extent might they have seemed modern to Rossetti’s readers?

- How painterly are the details in these poems? And why?

- What, if anything, is troubling or problematic about Rossetti’s use of symbolism? Consider, for instance, his description of the woodspurge as having “a cup of three.”