2.2: Historical Context

- Page ID

- 41775

As both a historical and literary age, the Victorian era dates chronologically with the reign of Queen Victoria. Some critics, though, see it as beginning with Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s (1809-1892) publication of Poems, Chiefly Lyrical and the opening of the Liverpool-Manchester railroad, both of which occurred in 1830.

As both a historical and literary age, the Victorian era dates chronologically with the reign of Queen Victoria. Some critics, though, see it as beginning with Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s (1809-1892) publication of Poems, Chiefly Lyrical and the opening of the Liverpool-Manchester railroad, both of which occurred in 1830.

The Victorian Age can be divided into two sections, with the fulcrum occurring around 1870. The first part was characterized by optimism in material, cultural, and social progress. The optimistic saw great progress occurring in this era. The Crimean War (1854-56), though filled with military miscalculations and deaths and achieved no victory, did not diminish this optimism. The second part, however, was affected by the Depression of 1873, which continued until the end of the century. England in the 1860s was at its zenith as a world power, followed by a slow decline over the next 100 years.

The paramount characteristic of the Victorian Age was rapid change and concomitant conflict. It was a complex age, an age of great wealth and extreme poverty, of the family as sacred center and a burgeoning of prostitution, of morality and fraud, of belief in the Bible and in scientific determinism. In the 1830s, railroad expansion transformed England as it spurred immense material progress and economic growth. The Victorians came to think of progress as natural and tied progress to wealth and prosperity.

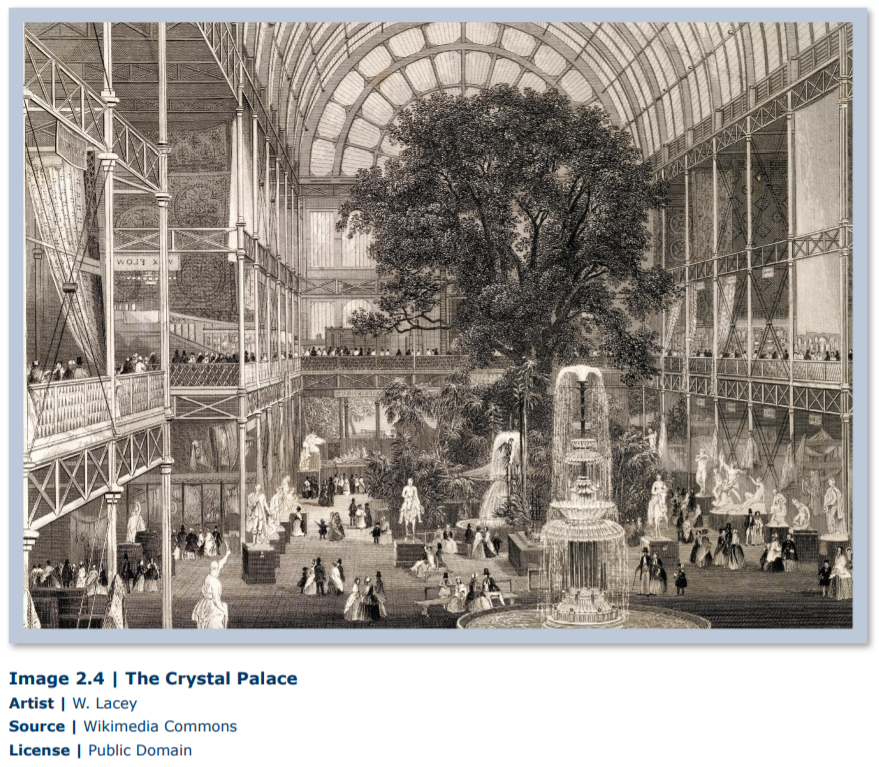

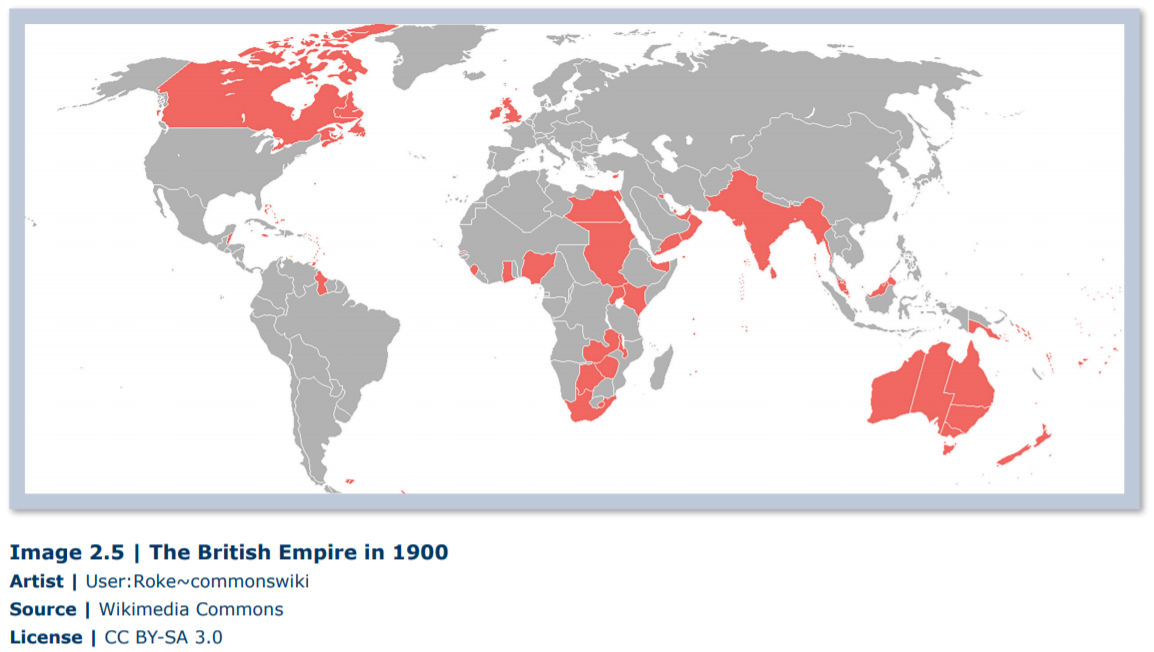

Britain exceeded the exports of competing nations like the United States by three to four times in number. The British Empire grew in pursuit of resources and markets for its exports. At its height of Empire, Britain ruled about a quarter of the world, including Ceylon, India, Australia, New Zealand, the Sudan, and South Africa. The British saw themselves as the leaders of the world, assuming the “white man’s burden” and spreading civilization and religion to the so-called dark places on earth. They overlooked the commercial exploitation, racism, and moral degradation that they also spread. A measure of Britain’s place in the world was The Crystal Palace (1851) which collected in one massive glass and iron structure inventions and artifacts taken from all over the British Empire.

During this economic and social transformation, England’s aristocracy and the rising middle class, comprising industrialists, businessmen, trade leaders, and workers, vied for political power, with the middle class incrementally overtaking the aristocracy. The Reform Bill of 1832 began the process of extending the franchise, ultimately reaching the worker. During this struggle, England shifted from an agrarian to an industrial society. Industrialization wrought a grim physical change on the landscape and in the growth of urban slums around factories. Farmers migrated from the country to the city. The population in London doubled in a matter of a few years. A dramatic increase in the population overall led to an urban concentration, in London and in northern industrial cities like Liverpool, Leeds, and Manchester.

The laboring masses of the poor, though, had little power. Men, women, and children lived in abysmal conditions, working six days a week for up to sixteen hours a day in factories and mines at a time when there were no minimum wage or age limits. These conditions were partially improved through various acts, including the Factory Act of 1833 that improved conditions in textile factories; the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 that created the Workhouse, a place intended for the desperate destitute as it separated families and forced able-bodied people to work alongside the lunatic and the ill; and the Mine Act of 1842 that excluded women and children from working underground. Nevertheless, women in particular remained considerably disadvantaged.

A large number of women worked as domestic servants and governesses. Prostitution was an option for the desperate, and the number of prostitutes increased tremendously. The Victorian connection of virtue with prosperity allowed what now seems a remarkable hypocrisy in this growth, as Victorians thought that the poor and the prostitute were “no better than they should be” and suffered poverty because of their moral laxity. The other side of this view was the Victorian feminine ideal that viewed women as the standard bearers of morality, as the protectors of virtue in the home, their natural sphere. A woman’s duty first was to her husband; a woman’s privilege was her freedom from the stress of the public sphere. A married woman’s property was in her husband’s hands up until the 1870s and 1880s. Despite their apparent spiritual and moral elevation, women were considered inferior to men intellectually, physically, and temperamentally, and the position of women became a concern for social change. Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847) spoke for women’s individuality, and John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women (1869) advocated for women’s education and options for occupations outside the domestic sphere.

Change and reform also occurred in religious life. Since the 1560s, England was a Protestant nation, with the Church of England supported by the government. Protestant evangelicals and dissenters of the church pushed strongly against this unquestioned authority, demanding strong Christian ethics and increased social welfare. Known for their religious fervor, evangelicals stressed the authority of the Bible, considering it to be the direct authority of God. Besides the Evangelical Movement there occurred in the 1870s the Oxford Movement that increased the size and power of the Roman Catholic Church. This movement was led by John Henry Newman (1801-1890) who published his spiritual biography Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1864).

These challenges to the established church reflected a shift in religion and philosophy caused by scientific and higher critical studies, including Sir Charles Lyell’s (1797-1875) Principles of Geology (1830-33) that used geology to measure the Earth’s age; Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) On the Origins of Species (1859) that saw life as biologically determined; and August Renan’s (1823-1894) Life of Jesus (1863), a biography of Jesus as human rather than divine. Additionally, the Empire exposed the British to unexpected diversity of cultures and religion.

Missionaries intent on spreading the word of God to the so-called heathen were taken by surprise at the rational skepticism of some of their intended converts. John William Colenso (1814-1883), the Bishop of Natal, described the impact of such skepticism in his controversial work of biblical criticism, The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua Critically Examined (1862).