1.8: The Research Paper

- Page ID

- 53678

Writing a Research Paper

The Purpose of Research Writing

Who has written poetry about exile? What roles did women play in the American Revolution? Where do cicadas go during their ‘off’ years? When did bookmakers start using movable type? Why was the Great Wall of China built? How does the human brain create, store, and retrieve memories?

You may know the answers to these questions off the top of your head. If you are like most people, however, you find answers to tough questions like these by searching the Internet, visiting a library, or asking others for information. To put it simply, you perform research.

Whether or not you realize it, you probably already perform research in your everyday life. When your boss, your instructor, or a family member asks you a question that you don’t know the answer to, you locate relevant information, analyze your findings, and share your results. Locating, analyzing, and sharing information are key steps in the research process. In this chapter, you will learn more about each step. By developing your research writing skills, you will prepare yourself to answer challenging questions.

Sometimes you perform research simply to satisfy your own curiosity. Once you find the answer to your questions, your search may be over, or it may lead to more in-depth research about that topic or about another topic. Other times, you want to communicate what you have learned to your peers, your family, your teachers, or even the editors of magazines, newspapers, or journals. In your personal life, you might simply discuss the topic with your friends. In more formal situations, such as in business and school, you communicate your findings in writing or in a presentation. A report may simply relay the results of your research in an organized manner. In contrast, a research paper presents an original thesis about a topic and develops that thesis with ideas and information gathered from a variety of sources. In a research paper, you use facts, interpretations, and opinions you encounter in your research to create a narrative and support an argument about your topic.

A student in an art history course might write a research paper about an artist’s work or an aesthetic movement. A student in a psychology course might write a research paper about current findings in childhood development. No matter what field of study you pursue, you will most likely be asked to write a research paper in your college degree program and to apply the skills of research and writing in your career. For similar reasons as professionals, students do research to answer specific questions, to share their findings with others, to increase their understanding of challenging topics, and to strengthen their analytical skills.

Having to write a research paper may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and writing a long paper requires a lot of time, effort, and organization. However, its challenges have rewards. The research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice. The writing process helps you to remember what you learned and to understand it on a deeper level. Thus writing a research paper can be a great opportunity to explore a topic that particularly interests you and to grow as a person. In this chapter, the topics include race relations and success as the focus of the theme-based readings.

Examples

Writing at Work

- Knowing how to write a good research paper is a valuable skill that will serve you well throughout your career. For example, laboratory technicians and information technology professionals do research to learn about the latest technological developments in their fields. A small business owner may conduct research to learn about the latest trends in his or her industry. A freelance writer will need to research his or her topics to write informed, up-to-date articles. Whether you are developing a new product, studying the best way to perform a procedure, discovering the challenges and opportunities in your field of employment, or learning about how to find a job, you will use research techniques to guide your exploration. Because effective communication is essential to any company, employers seek to hire people who can write clearly and professionally

EXERCISE 1

Think about the job of your dreams. How might you use research writing skills to perform that job? Create a list of ways in which strong researching, organizing, writing, and critical thinking skills could help you succeed at your dream job. How might these skills help you obtain that job?

Process Overview

How does a research paper grow from a folder of notes to a polished final draft? No two projects are identical, but most writers of research papers follow six basic steps.

Step 1: Choosing a TopicHome

To narrow the focus of your topic, brainstorm using Prewriting Techniques. Starting with your topic, formulate a specific research question—a broad, open-ended question that will guide your research—as well as propose a possible answer, or a working thesis.

Step 2: Planning and Scheduling

Before you start researching your topic, take time to plan your researching and writing schedule. Research projects can take days, weeks, or even months to complete.

Creating a schedule is a good way to ensure that you do not end up being overwhelmed by all the work you have to do as the deadline approaches. During this step of the process, it is also a good idea to plan the resources and organizational tools you will use to keep yourself on track throughout the project. Flowcharts, calendars, and checklists can all help you stick to your schedule.

Step 3: Conducting ResearchHome

When going about your research, you will likely use a variety of sources—anything from books and periodicals to video presentations and in-person interviews. However, you should pay close attention to instructions; instructors often specify what kinds of sources they require for research papers. Some may assign you to only use scholarly (peer-reviewed) sources. For some assignments, your sources might include both primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources provide firsthand information or raw data. For example, surveys, in-person interviews, historical documents, works of art, and works of literature are primary sources. Secondary sources, such as biographies, literary reviews, or news articles, include some analysis or interpretation of the information presented. As you conduct research, you should take detailed, careful notes about your discoveries. You should also evaluate the reliability of each source you find, especially sources that are not peer-reviewed.

Step 4: Organizing Your Research and Ideas

When your research is complete, you will organize your findings and decide which sources to cite in your paper. You will also have an opportunity to evaluate the evidence you have collected and determine whether it supports your thesis, or the focus of your paper. You may decide to adjust your thesis or conduct additional research to ensure that your thesis is well supported.

Step 5: Drafting Your Paper

Now you are ready to combine your research findings with your critical analysis of the results in a rough draft. You will incorporate source materials into your paper and discuss each source thoughtfully in relation to your thesis or purpose statement. It is important to pay close attention to standard conventions for citing sources in order to avoid plagiarism, which is the practice of using someone else’s words without acknowledging the source. You will learn how to incorporate sources in your paper and avoid some of the most common pitfalls of attributing information.

Step 6: Revising and Editing Your Paper

In the final step of the research writing process, you will revise and polish your paper. You might reorganize your paper’s structure or revise for unity and cohesion, ensuring that each element in your paper smoothly and logically flows into the next. You will also make sure that your paper uses an appropriate and consistent tone. Once you feel confident in the strength of your writing, you will edit your paper for proper spelling, grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting. When you complete this final step, you will have transformed a simple idea or question into a thoroughly researched and well-written paper of which you can be proud.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Choosing Your Topic

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions and a working thesis. It’s important to set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Identifying Potential Topics

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. Choosing a topic that genuinely interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask you to develop a topic on your own. You may find inspiration for topic ideas in your everyday life, by browsing magazines, or looking at lists of topics or themes in online databases such Opposing Viewpoints, CQ Researcher Online, Bloom’s Literary Reference Online, and Literature Resource Center. In addition to Prewriting Techniques, use tools on the Web, such as Wridea, to help you brainstorm your topic.

You may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. Building a list of potential topics will help you to identify additional, related topics. In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying healthcare administration, as he prepares a research paper. Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on current debates about healthy living for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed the following list of possibilities:

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Medial portrayals of health care reform

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, H1N1, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

- Race Relations

- Success

Focusing on a Topic

After identifying potential topics, you will need to evaluate your list and choose one topic to pursue as the focus of your research paper. Discussing your ideas with your instructor, peers, and tutors will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment. The following are some questions to consider:

- Will you be able to find enough information about the topic?

- Can you take an arguable position on the topic?

- Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify the topic so it is more manageable?

You will also need to narrow your topic so you can formulate a concise, manageable thesis about it. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being so narrow that they can’t sustain an entire research paper. A good research paper provides focused, in- depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing. Also, conduct preliminary research, including discussing the topic with others.

You may be asking yourself, “How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through Prewriting Techniques. Taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles. For example, Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment.

He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s following ideas from freewriting.

Our instructors are always saying that accurate, up-to-date information is crucial in encouraging people to make better choices about their health. I don’t think the media does a very good job of providing that, though. Every time I go on the Internet, I see tons of ads for the latest ‘miracle food’. One week it’s acai berries, the next week it’s green tea, and then six months later I see a news story saying all the fabulous claims about acai berries and green tea are overblown! Advice about weight loss is even worse. Think about all the diet books that are out there! Some say that a low-fat diet is best; some say you should cut down on carbs; and some make bizarre recommendations like eating half a grapefruit with every meal. I don’t know how anybody is supposed to make an informed decision about what to eat when there’s so much confusing, contradictory information. I bet even doctors, nurses, and dietitians have trouble figuring out what information is reliable and what is just the latest hype.

Another way that writers focus on a topic is by conducting preliminary research. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, friends, and family. Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web is a good way to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic in online newspapers, magazines, blogs, and discussion boards. Keep in mind that the reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later; however, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea, search for some fully developed sources on that topic to see if it’s worth pursuing. If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities to identify potential topics. Remind yourself of reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue. If the readings or viewings assigned in your course deal with your topic, then review and take notes on those materials. Librarians and instructors can help you to determine if there are enough sources available on your topic, or if there are so many sources that it would be wise to narrow your topic further.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of current debates about healthy living intersected with a few of his own interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects. Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Examples

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of sources and take notes on your findings.

EXERCISE 2Home

Set a timer for five minutes. Use Prewriting Techniques to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? Do you closely follow a particular social media website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Would you like to learn more about people’s use of the Internet to build support for social causes? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

EXERCISE 3

Choose two topics from the list you created above. Spend five minutes freewriting about each of these topics. Choose the topic that you enjoyed freewriting about the most. Then, review your freewriting to identify possible areas of focus.

EXERCISE 4

Collaborative exercise: Swap lists of potential topics with a classmate. Select one or two topics on your classmate’s list about which you would like to learn more. Explain to your classmate why you find those topics interesting. Ask your classmate which of the topics on your list s/he would like to learn more about and why.

Determining Paths of Inquiry

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing research questions and a working thesis.

By forming research questions about your topic, you are setting a goal for your research. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several sub-questions that you will need to research in more depth to answer your main question. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer. Review the results of your prewriting, and skim through your preliminary research. From these, write both simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation to answer.

Below are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his sub-questions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Topic: Low-carbohydrate diets

Main question : Are low-carbohydrate diets as effective as they have been portrayed to be by media sources?

Subquestions :

-

- Who can benefit from following a low-carbohydrate diet?

- What are the supposed advantages to following a low-carbohydrate diet?

- When did low-carbohydrate diets become a ‘hot’ topic in the media?

- Where do average consumers get information about diet and nutrition?

- Why has the low-carb approach received so much media attention?

- How do low-carb diets work?

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason: it is subject to modification. You may adapt your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not hesitate to change your path as you learn about your topic.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete statements that begin, “I believe…” or “My opinion is…”. These first-person phrases are useful starting points even though you may eventually omit them from sentences in your research paper. Generally, formal research papers use an assertive, objective voice and, therefore, do not include first-person pronouns. Some readers associate I with informal, subjective writing. Some readers think the first-person point of view diminishes the impact of a claim. For these reasons, some instructors will tell you not to use I in research papers.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, below, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

Main Research Question: Are low-carb diets as effective as they have sometimes been portrayed to be by the mass media?

Working Thesis Statement: Low-carb diets do not live up to the media hype surrounding them.

Examples

Writing at Work

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal for an academic purpose. Both define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

EXERCISE 5

Using the topic you have selected, write your main research question and at least four sub-questions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

EXERCISE 6

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote above. Think about whether your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Managing Your Research

Step 1 “Choosing a Topic,” helped you begin to plan the content of your research paper—your topic, research questions, and preliminary thesis. It is equally important to plan out the process of researching and writing the paper. Although some types of writing assignments can be completed relatively quickly, developing a good research paper is a complex process that takes time and attention. Careful planning helps ensure that you will keep your project running smoothly and produce your best work. Think about how you will complete each step and what resources you will use. Resources may include anything from online databases and digital technologies to interview subjects and writing tutors.

Scheduling Research and Writing

Set up a project schedule that shows when you will complete each step. To develop your schedule, use a calendar and work backward from the date your final draft is due. Generally, it is wise to divide half of the available time on the research phase of the project and half on the writing phase. For example, if you have a month to work, plan for two weeks for each phase. If you have a full semester, plan to begin research early and to start writing by the middle of the term. You might think that no one really works that far ahead, but try it. You will probably be pleased with the quality of your work and with the reduction in your stress level.

Plan your schedule realistically, and consider other commitments that may sometimes take precedence. A business trip or family visit may mean that you are unable to work on the research project for a few days. Make the most of the time you have available. Plan for unexpected interruptions, but keep in mind that a short time away from the project may help you come back to it with renewed enthusiasm. Another strategy many writers find helpful is to finish each day’s work at a point when the next task is an easy one. That makes it easier to start again.

As you plan, break down major steps into smaller tasks if necessary. For example, Step3, Conducting Research, involves locating potential sources, evaluating their usefulness and reliability, reading, and taking notes. Defining these smaller tasks makes the project more manageable by giving you concrete goals to achieve.

Jorge had six weeks to complete his research project. Working backward from a due date of May 2, he mapped out a schedule for completing his research by early April so that he would have ample time to write. Jorge chose to write his schedule in his weekly planner to help keep himself on track. Review Jorge’s schedule. Key target dates are shaded. Note that Jorge planned times to use available resources by visiting the library and writing center and by meeting with his instructor.

Sample Schedule for Writing a Research Paper

Staying Organized

Although setting up a schedule is relatively easy, sticking to one is challenging. Even if you are the rare person who never procrastinates, unforeseen events may interfere with your ability to complete tasks on time. A self-imposed deadline may slip your mind despite your best intentions. Organizational tools (e.g., calendars, checklists, note cards, software) and setting up a buddy system with a classmate can help you stay on track.

Throughout your project, organize both your time and resources systematically. Review your schedule frequently and check your progress. It helps to post your schedule in a place where you will see it every day. Email systems usually include a calendar feature where you can record tasks, arrange to receive daily reminders, and check off completed tasks. Electronic devices such as smartphones have similar features. There are online task-management tools you may use for free on the Web, such as Google Tasks, HiTask, Nirvana, and Remember the Milk. Some people enjoy using the most up-to-date technology to help them stay organized. Other people prefer simple methods, such as crossing off items on a checklist. The key to staying organized is finding a system you like enough to use daily. The particulars of the method are not important as long as you are consistent.

Organize project documents in a binder or digital folder. Label these clearly. Use note cards, an electronic document, an online database folder (this will require you to set up a free account on the database), or free downloadable software such as Zotero to record bibliographical information for sources you want to use in your paper. Tracking this information during the research process will save you time when Creatinga List of References.

Examples

Writing at Work

When you create a project schedule at work, you set target dates for completing certain tasks and identify the resources you plan to use on the project. It is important to build in some flexibility. Materials may not be received on time because of a shipping delay. An employee on your team may be called away to work on a higher-priority project. Essential equipment may malfunction. You should always plan for the unexpected.

EXERCISE 7

Working backward from the date your final draft is due, create a project schedule. You may choose to write a sequential list of tasks, record tasks on a calendar, or set up your project’s timeline using an online task-management tool, such as Google Tasks, HiTask, Nirvana, and Remember the Milk. Select a format you think will help you stay on track from day to day. Use a calendar accessible on your smartphone, record your schedule in a weekly planner, post it by your desk, or set your email or task-management tool to send you reminders. Review your schedule to be sure you have broken each step into smaller tasks and assigned a target completion date to each key task. Review your target dates to make sure they are realistic.

Allow more time than you think you will need.

Anticipating Challenges

Do any of these scenarios sound familiar? You have identified a book that would be a great resource for your project, but it is currently checked out of the library. You planned to interview a subject-matter expert on your topic, but she calls to cancel. You have begun writing your draft, but now you realize that you will need to modify your thesis and conduct additional research. Or, you have finally completed your draft when your computer crashes, and days of hard work disappear in an instant. These troubling situations are all too common. No matter how carefully you plan your schedule, you may encounter a glitch or setback. Managing your project effectively means anticipating potential problems, taking steps to minimize them where possible, and allowing time in your schedule to handle any setbacks.

Many times a situation becomes a problem due only to lack of planning. For example, if a book is checked out of your college’s library, you can request it through interlibrary loan to have it delivered to your campus in a few days. Alternatively, you might locate another equally useful source. If you have allowed enough time for research, a brief delay will not become a major setback.

You can manage other potential problems by staying organized and maintaining a take-charge attitude. Take the time to save a backup copy of your work on a portable flash drive. Or, instead of using the hard drive of one computer to save your work, create your word-processing files using cloud storage such as Dropbox or Google Drive, which you can access with a username and password from any computer with an Internet connection. If you don’t have a reliable Internet connection off campus, then visit a computer lab on campus or a public library with desktop computers, or you can go to a coffee shop with a laptop; it is important to find a space where you can concentrate and that is open during times that work with your schedule. As you conduct research, maintain detailed records and notes of sources—doing so will make citing sources in your draft infinitely easier. If you run into difficulties with your research or your writing, ask your instructor or a librarian for help, or meet with a peer or writing tutor.

Examples

Writing at Work

In the workplace, documents prepared at the beginning of a project often include a detailed plan for risk management. When you manage a project, it makes sense to anticipate and prepare for potential setbacks. For example, to roll out a new product line, a software development company must strive to complete tasks on a schedule in order to meet the new product release date. The project manager may need to adjust the project plan if one or more tasks fall behind schedule.

EXERCISE 8

Identify five potential problems you might encounter in the process of researching and writing your paper. Write them on a separate sheet of paper. For each problem, write at least one strategy for solving the problem or minimizing its effect on your project.

Gathering Your Sources

Now that you have planned your research project, you are ready to begin the research. This phase can be both exciting and challenging. As you read this section, you will learn ways to locate sources efficiently, so you will have enough time to read the sources, take notes, and think about how to use them in your research paper. In addition to finding sources, research entails determining the relevance and reliability of sources, organizing findings, as well as deciding whether and how to use sources in your paper. The technological advances of the past few decades—particularly the rise of online media—mean that, as a twenty-first-century student, you have countless sources of information available at your fingertips. But how can you tell whether a source is reliable? This section will discuss strategies for finding and evaluating sources so that you can be a media-savvy researcher.

Depending on your assignment, you will likely search for sources by using:

- Internet search engines to locate sources freely available on the web.

- A library’s online catalog to identify print books, ebooks, periodicals, DVDs, and other items in the library’s collection. The catalog will help you find journals by title, but it will not list the journal’s articles by title or author.

- Online databases to locate articles, ebooks, streaming videos, images, and other electronic resources. These databases can also help you identify articles in print periodicals.

Your instructor, as well as writing tutors and librarians, at your college can help you determine which of these methods will best fit your project and learn to use the search tools available to you. You can also find research guides and tutorials on library websites and YouTube channels that can help you identify appropriate research tools and learn how to use them. As you gather sources, you will need to examine them with a critical eye. Smart researchers continually ask themselves two questions: “Is this source relevant to my purpose?” and “Is this source reliable?” The first question will help you avoid wasting valuable time reading sources that stray too far from your specific topic and research questions. The second question will help you find accurate, trustworthy sources.

Examples

Writing at Work

Businesses, government organizations, and nonprofit organizations produce published materials that range from brief advertisements and brochures to lengthy, detailed reports. In many cases, producing these publications requires research. A corporation’s annual report may include research about economic or industry trends. A charitable organization may use information from research in materials sent to potential donors. Regardless of the industry you work in, you may be asked to assist in developing materials for publication. Often, incorporating research in these documents can make them more effective in informing or persuading readers.

Identifying Primary and Secondary Sources

When you chose a paper topic and determined your research questions, you conducted preliminary research to stimulate your thinking. Your research plan included some general ideas for how to go about your research—for instance, interviewing an expert in the field or analyzing the content of popular magazines. You may even have identified a few potential sources. Now it is time to conduct a more focused, systematic search for informative primary and secondary sources. Writers classify research resources in two categories: primary sources and secondary sources.

Primary sources are direct, firsthand sources of information or data. For example, if you were writing a paper about the First Amendment right to freedom of speech, the text of the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights would be a primary source. Other primary sources include the following:

- Data

- Works of visual art

- Literary texts

- Historical documents such as diaries or letters

- Autobiographies, interviews, or other personal accounts

Secondary sources discuss, interpret, analyze, consolidate, or otherwise rework information from primary sources. In researching a paper about the First Amendment, you might read articles about legal cases that involved First Amendment rights, or editorials expressing commentary on the First Amendment. These sources would be considered secondary sources because they are one step removed from the primary source of information. The following are examples of secondary sources:

- Literary criticism

- Biographies

- Reviews

- Documentaries

- News reports

Your topic and purpose determine whether you must cite both primary and secondary sources in your paper. Ask yourself which sources are most likely to provide the information that will answer your research questions. If you are writing a research paper about reality television shows, you will need to use some reality shows as a primary source, but secondary sources, such as a reviewer’s critique, are also important. If you are writing about the health effects of nicotine, you will probably want to read the published results of scientific studies, but secondary sources, such as magazine articles discussing the outcome of a recent study, may also be helpful.

Some sources could be considered primary or secondary sources, depending on the writer’s purpose for using them. For instance, if a writer’s purpose is to inform readers about how the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation has affected elementary education in the United States, then a Time magazine article on the subject would be a secondary source. However, suppose the writer’s purpose is to analyze how the news media has portrayed the effects of NCLB. In that case, articles about the legislation in news magazines like Time, Newsweek, and US News & World Report would be primary sources. They provide firsthand examples of the media coverage the writer is analyzing.

Once you have thought about what kinds of sources are most likely to help you answer your research questions, you may begin your search for sources. The challenge here is to conduct your search both efficiently and thoroughly. On the one hand, effective writers use strategies to help them find the sources that are most relevant and reliable while steering clear of sources that will not be useful; on the other hand, they are open to pursuing different lines of inquiry that come up along the way than those that seemed relevant at the start of research. As a process of discovery, good research requires critical thinking about, and often revising of, writers’ plans and ideas.

Reading Popular and Scholarly Periodicals

When you search for periodicals, be sure to distinguish among different types. Mass-market publications, such as newspapers and popular magazines, differ from scholarly publications in their accessibility, audience, and purpose. Newspapers and magazines are written for a broader audience than scholarly journals. Their content is usually quite accessible and easy to read. Trade magazines that target readers within a particular industry may presume the reader has background knowledge, but these publications are still reader-friendly for a broader audience. Their purpose is to inform and, often, to entertain or persuade readers as well.

Scholarly or academic journals are written for a much smaller and more expert audience. The creators of these publications are experts in the subject and assume that most of their readers are already familiar with the main topic of the journal. The target audience is also highly educated. Informing is the primary purpose of a scholarly journal. While a journal article may advance an agenda or advocate a position, the content will still be presented in an objective style and formal tone. Entertaining readers with breezy comments and splashy graphics is not a priority.

Because of these differences, scholarly journals are more challenging to read. That doesn’t mean you should avoid them. On the contrary, they can provide in-depth information unavailable elsewhere. Because knowledgeable professionals carefully review the content before publication in a process called “peer-review,” scholarly journals are far more reliable than much of the information available in popular media. Seek out academic journals along with other resources. Just be prepared to spend a little more time processing the information.

Examples

Writing at Work

Periodicals databases are not just for students writing research papers. They also provide a valuable service to workers in various fields. The owner of a small business might use a database such as Business Source Premiere to find articles on management, finance, or trends within a particular industry. Health care professionals might consult databases such as MedLine to research a particular disease or medication. Regardless of what career path you plan to pursue, periodicals databases can be a useful tool for researching specific topics and identifying periodicals that will help you keep up with the latest news in your industry.

Using Sources from the Open Web

When faced with the challenge of writing a research paper, some students rely on popular search engines, such as Google, as their only source of information. Typing a keyword or phrase into a search engine instantly pulls up links to dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of related websites—what could be easier? While the Web is useful for retrieving information, you should be wary of limiting your research to sources from the open Web.

For example, wikis, including online encyclopedias, such as Wikipedia, and community- driven question-and-answer sites, such Yahoo Answers, are very easy to access on the Web. They are free, and they appear among the first few results when using a search engine. Because these sites are created and revised by a large community of users, they cover thousands of topics, and many are written in an informal and straightforward writing style. However, these sites may not have a reliable control system for researching, writing, and reviewing posts. While wikis may be a good starting point for finding other, more trustworthy, more fully developed sources, usually they should not be your final sources.

Despite its apparent convenience, researching on the open Web has the following drawbacks to consider:

- Results do not consider the reliability of the sources. The first few hits that appear in search results often include sites whose content is not always reliable. Search engines cannot tell you which sites have accurate information.

- Results may be influenced by popularity or advertisers. Search engines find websites that people visit often and list the results in order of popularity rather than relevance to your topic.

- Results may be too numerous for you to use. Search engines often return an overwhelming number of results. Because it is difficult to filter results for quality or relevance, the most useful sites may be buried deep within your search results. It is not realistic for you to examine every site.

- Results do not include many of the library’s high quality electronic resources that are only available through password-protected databases or on campus.

- Because anyone can publish anything on the Web, the quality of the information varies greatly and you will need to evaluate web resources carefully.

Nevertheless, a search on the open Web can provide a helpful overview of a topic and may pull up genuinely useful sources. You may find specialized search engines recommended on your college library’s website. For example, http://www.usa.gov will search for information on United States government websites. If you are working at your personal computer, use the Bookmarks or Favorites feature of your web browser to save and organize sites that look promising.

To get the most out of a search engine, use strategies to make your search more efficient. Depending on the specific search engine you use, the following options may be available:

- Limit results to websites that have been updated within a particular time frame.

- Limit results by language or region.

- Limit results to scholarly works available online. Google Scholar is an example.

- Limit results by file type.

- Limit results to a particular site or domain type, such as .edu (school and university sites) or .gov (government sites). This is a quick way to filter out commercial sites that often lead to less objective results.

Types and Formats of Library Sources

Information accessible through a college library comes in a variety of types and formats of sources. Books, DVDS, and various types of periodicals can be found in physical form at the library. Many of these same materials are available in electronic format in the form of ebooks, electronic journal articles, and streaming videos. Your college library may have some resources in both print and electronic formats while others may be available exclusively in one format. The following lists different types of resources available at college libraries. In addition to the resources noted, library holdings may include primary sources such as historical documents, letters, diaries, and images.

Types of sources

- Reference works provide a summary of information about a particular topic. Almanacs, encyclopedias, atlases, medical reference books, and scientific abstracts are examples of reference works. In most cases, reference books may not be checked out of a library. Note that reference works are many steps removed from original primary sources and are often brief, so these should be used only as a starting point when you gather information.

- Examples: The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2010; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, published by the American Psychiatric

- Nonfiction books provide in-depth coverage of a topic. Trade books, biographies, and how-to guides are usually written for a general audience. Scholarly books and scientific studies are usually written for an audience that has specialized knowledge of a topic.

- Examples: The Low-Carb Solution: A Slimmer You in 30 Days; Carbohydrates, Fats and Proteins: Exploring the Relationship Between Macronutrient Ratios and Health Outcomes.

- Periodicals are published at regular intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly. Newspapers, magazines, and academic journals are different kinds of periodicals. Some periodicals provide articles on subjects of general interest while others are more specialized.

- Examples: The New York Times; PC Magazine; JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association.

- Government publications by federal, state, and local agencies publish information on a variety of topics. Government publications include reports, legislation, court documents, public records, statistics, studies, guides, programs, and forms.

- Examples: The Census 2000 Profile; The Business Relocation Package, published by the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.

- Business publications and publications by nonprofit organizations are designed to market a product, provide background about the organization, provide information on topics connected to the organization, or promote a cause. These publications include reports, newsletters, advertisements, manuals, brochures, and other print documents.

- Examples: a company’s instruction manual explaining how to use a specific software program; a news release published by the Sierra

- Documentaries are the moving-image equivalent of nonfiction books. They cover a range of topics and can be introductory or scholarly.Newsreels can be primary sources about then-current events. Feature- length programs or episodes of a series can be secondary sources about historical phenomena or life stories. You may view a documentary in amovie theater, on television, on an open website, or in a subscription- accessed database such as Films on Demand.

- Examples: Freedom Riders, directed by Stanley Nelson; Finding Your Roots, with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

As you gather information, strive for a balance of accessible, easy-to-read sources and more specialized, challenging sources. Relying solely on lightweight books and articles written for a general audience will drastically limit the range of useful, substantial information. However, restricting oneself to dense, scholarly works could make the research process overwhelming. An effective strategy for unfamiliar topics is to begin your reading with works written for the general public, and then move to more scholarly works as you learn more about your topic.

Using Databases

While library catalogs can help you locate print and electronic book-length sources, as well as some types of non-print holdings, such as CDs, DVDs, and audiobooks, the best way to locate shorter sources, such as articles in magazines, newspapers, and journals, is to search online databases accessible through a portal to which your college’s library subscribes. In many cases, the full texts of articles are available from these databases. In other instances, articles are indexed, meaning there is a summary and publication information about the article, but the full text is not immediately available in the database; instead, you may find the indexed article in a print periodical in your college’s library holdings, or you can submit an online request for an interlibrary loan, and a librarian will email a digitized copy of the article to you.

When searching for sources using a password-protected portals, it’s important to understand where and how to look up your topic. On its homepage, the LAVC Library, contains a general search bar called the “One Search” tool, which allows you to search many (but not all) databases at once. If you don’t find useful sources using the portal’s general search bar, then you may retrieve better results by going to specific databases within the portal. Additionally, for specific guidance on using a password-protected portal to find sources for a literary research paper, watch videos in the GPC Libraries’ “Literature Research Series” on YouTube. As these tutorials show, on a portal such as GALILEO, you can choose specific databases by going to “Databases A-Z” or “Databases by Subject.” Databases may be general, including many types of resources on a broad range of subjects, or they may be specialized, focusing on a particular format of resource or a specific subject area. The following list describes some commonly used indexes and databases accessible through libraries’ research portals.

- Academic Search Complete includes articles on a wide variety of topics published in various forums, both scholarly and popular.

- Opposing Viewpoints includes articles, statistics, and recommended websites related to a wide range of controversial issues.

- CQ Researcher Online has full-text articles about issues in the news

- Lexis Nexis has articles from newspapers and other periodicals, news transcripts, and business and legal information.

- Business Source Complete comprises business-related content from magazines, journals, and trade publications.

- Films on Demand has streaming video of documentaries and historic newsreels.

- Artstor has high-quality images of works of visual art of various media, as well as information on the creators, subjects, materials, and holdings of artworks.

- JSTOR includes full-text scholarly secondary sources, including books and articles, as well as primary sources on a wide variety of topics, mostly in the humanities and social sciences.

- History Reference Center has full-text articles from reference books, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, as well as images and streaming videos on most of the world’s cultures and time periods.

- Literature Resource Center includes full-text print and electronic sources relevant to literature, such as biographies of authors, reviews of works, overviews of plots and characters, analyses of themes, and scholarly criticism.

- Science and Technology Collection has full-text articles from journals in various scientific and technical fields.

- MEDLINE, Proquest Nursing, and Consumer Health Source contain articles in medicine and health.

Sometimes you will know exactly which source you are looking for, for example, if your instructor or another writer references that source. Having the author (if available), title, and other information about the source included in an end-of-text citation will help you to find that source.

As you go through the process of gathering sources, you will likely need to find specific sources referenced by others to build your list of useful sources; use the steps above to help you do this. However, keep in mind that, especially when you first start researching, you will also need to find sources about your topic having little or no idea what sources are out there. Therefore, rather than authors and titles, you will need to enter keywords, or subject search terms, related to your topic. The next section instructs you on how to do that.

Entering Search Terms

One of the most important steps in conducting research is to “learn how to speak database,” as the sock puppet explains to the student in this video tutorial, titled “How toUse a Database,” created by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga (UTC) Library. As the video shows, to find reliable sources efficiently, you must identify single words or phrases that represent the major concepts of your research—that is, your keywords, or subject search terms. Your starting points for developing search terms are the topic and the research questions you identify, but you should also think of synonyms for those terms. Furthermore, as you begin searching for sources, you should notice additional terms in the subjects listed in the records of your results. These subjects will help you find additional sources.

As Jorge used his library’s catalog and databases, he worked to refine his search by making note of subjects associated with sources about low-carb dieting. His search helped him to identify the following additional terms and related topics to research:

- Low-carbohydrate diet

- Insulin resistance reducing diets

- Glycemic index

- Dietary carbohydrates

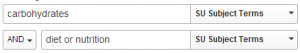

Searching the library’s online resources is similar in many ways to searching the Internet, except some library catalogs and databases require specific search techniques. For example, some databases require that you use Boolean operators to connect your search terms. In other databases, Boolean operators are optional, but can still help you get better search results. Here are some of the ways you can use Boolean operators:

- Connect keywords with AND to limit results to citations that include both keywords—for example, carbohydrates AND diet.

- Connect keywords with OR to search for results that contain either of two terms. For example, searching for diet OR nutrition locates articles that use “diet” as a keyword as well as articles that use “nutrition” as a keyword.

- Connect keywords with NOT to search for the first word without the second. This can help you eliminate irrelevant results based on words that are similar to your search term. For example, searching for obesity NOT childhood locates materials on obesity but excludes materials on childhood obesity.

- Enclose a phrase in quotation marks to search for an exact phrase, such as “morbid obesity.”

Many databases offer tools for improving your search. Make your search in library catalogs and databases more effective by using the following tips:

- Use limiters (often located on the left side of the search results) to further refine your results after searching.

- Change the sort of your results so the order of the articles best fits your needs. Sorting by date allows you to put the most recent or the oldest articles at the top of the results list. Other types of sorts include relevance, alphabetical by author’s name or alphabetical by article title.

- Use the Advanced Search functions of your database to further refine your results or to create more complex combinations of search terms.

- Use the Help section of the database to find more search strategies that apply to that particular database.

Here is an example of using Boolean operators in an Advanced Search:

Consulting a Reference Librarian

Sifting through library stacks and database search results to find the information you need can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Knowing the right keywords can sometimes make all the difference in conducting a successful search. If you are not sure how you should begin your search, or if your search is yielding too many, or too few, results, then you are not alone. Many students find this process challenging, although it does get easier with experience. One way to learn better search strategies is to consult a reference librarian and watch online tutorials that research experts have created to help you. If you have trouble finding sources on a topic, consult a librarian.

Reference librarians are intimately familiar with the systems that libraries use to organize and classify information. They can help you locate a particular book in the library stacks, steer you toward useful reference works, and provide tips on how to use databases and other electronic research tools. Take the time to see what resources you can find on your own, but if you encounter difficulties, ask for help. Many academic librarians are available for online chatting, texting, and emailing as well as face-to-face reference consultations. To make the most of your reference consultation, be prepared to explain, to the librarian, the assignment and your timeline as well as your research questions and ideas for keywords. Because they are familiar with the resources available, librarians may be able to recommend specific resources that fit your needs and tailor your keywords to the search tools you are using.

EXERCISE 9

At the Library of Congress’s website, search for results on a few terms related to your topic. Review your search results to identify six to eight additional terms you might use when you search for sources using your college library’s catalog and databases.

EXERCISE 10

Visit your library’s website or consult with a reference librarian to determine which databases would be useful for your research. Depending on your topic, you may rely on a general database, a specialized database for a particular subject area, or both. Identify at least two relevant databases. Conduct a keyword search in these databases to find potentially relevant sources on your topic. Also, search your college’s online library catalog. If the catalog or database you are using provides abstracts of sources, then read them to determine how useful the sources are likely to be. Print out, email to yourself, or save your search results.

EXERCISE 11

In your list of results, identify three to five sources to review more closely. If the full text is available online, set aside time to open, save, and read it. If not, use the “Find It” tool to see if the source is available through your college’s library. Visit the library to locate any sources you need that are only available in print. If the source is not available directly through your school’s library, then use the library’s online tool to request an interlibrary loan of the source: librarians will send the source in digital form to your email address for you to open and save, or they will send it in print form to your campus library for you to check out.

Evaluating and Processing Your Sources

Determining Whether a Source Is Relevant

At this point in your research process, you may have identified dozens of potential sources. It is easy for writers to get so caught up in checking out books and printing out articles that they forget to ask themselves how they will use these resources in their research. Now is a good time to get a little ruthless. Reading and taking notes takes time and energy, so you will want to focus on the most relevant sources.

You may benefit from seeking out sources that are current, or up to date. Depending on your topic, sources may become outdated relatively soon after publication, or they may remain useful for years. For instance, online social networking sites have evolved rapidly over the past few years. An article published in 2002 about this topic will not provide current information. On the other hand, a research paper on elementary education practices might refer to studies published decades ago by influential child psychologists. When using websites for research, look on the web-page to see when the site was last updated. Many non-functioning links are a sign that a website is not regularly updated. Do not be afraid to ask your instructor, tutors, and librarians for suggestions if you find that many of your most relevant sources are not especially reliable, or that your most reliable sources are not relevant.

To weed through your collection of books and articles, skim their contents. Read quickly with your research questions and subtopics in mind. The following tips explain how to skim to get a quick sense of what topics are covered. If a book or article is not especially relevant, put it aside. You can always come back to it later if you need to.

Tips for Skimming Books

-

- Read the book cover and table of contents for a broad overview of the topics covered.

- Use the index to locate more specific topics and see how thoroughly they are covered.

- Flip through the book and look for subtitles or key terms that correspond to your research.

Tips for Skimming Articles

-

- Journal articles often begin with an abstract or summary of the contents. Read it to determine the article’s relevance to your research.

- Skim the introduction and conclusion for summary material.

- Skim through subheadings and text features such as sidebars.

- Look for keywords related to your topic.

Determining Whether a Source Is Reliable

All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious. To evaluate your research sources, you will use critical thinking skills consciously and deliberately.

Sources you encounter will be written for distinct purposes and with particular audiences in mind, which may account for differences such as the following:

- How thoroughly writers cover a given topic

- How carefully writers research and document facts How editors review the work

- What biases or agendas affect the content

A journal article written for an academic audience for the purpose of expanding scholarship in a given field will take an approach quite different from a magazine feature written to inform a general audience. Textbooks, hard news articles, and websites approach a subject from different angles as well. To some extent, the type of source provides clues about its overall depth and reliability. Use the following descriptions of types of sources to help you determine the quality of your sources.

- High Quality Sources provide the most in-depth information. They are written and reviewed by subject-matter experts. Examples: books published by University presses and articles in scholarly journals, such as Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature; trade books and magazines geared toward an educated general audience, such as Smithsonian Magazine; government documents; documents by reputable organizations, such as universities and research institutes.

- Varied Quality Sources are often useful; however, they do not cover subjects in as much depth as high-quality sources, and they are not always rigorously researched and reviewed. Some, such as popular magazine articles or company brochures, may be written to market a product or a cause. Textbooks and reference books are usually reliable, but they may not cover a topic in great depth. Use them with caution.Examples: news stories and feature articles (print or online) from reputable newspapers, magazines, or organizations, such as The New York Times or the Public Broadcasting Service; popular magazine articles, which may or may not be carefully researched and fact checked; documents by businesses and nonprofit organizations.

- Questionable Sources are often written primarily to attract a large readership or to present the author’s opinions, and they are not subject to careful review. Generally, avoid using these as final sources. If you want to use a source that fits into this category, then carefully evaluate it using criteria below. Examples: loosely regulated or unregulated media content, such as Internet discussion boards, blogs, free online encyclopedias, talk shows, television news shows with obvious political biases, personal websites, and chat rooms.

Even when you are using a type of source that is generally reliable, you will still need to evaluate the author’s credibility and the publication itself on an individual basis. To examine the author’s credibility—that is, how much you can believe of what the author has to say—examine his or her credentials. What career experience or academic study shows that the author has the expertise to write about this topic? Keep in mind that expertise in one field is no guarantee of expertise in another, unrelated area. For instance, an author may have an advanced degree in physiology, but this credential is not a valid qualification for writing about psychology. Check credentials carefully.

Just as important as the author’s credibility is the publication’s overall reputability. Reputability refers to a source’s standing and reputation as a respectable, reliable source of information. An established and well-known newspaper, such as The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal, is more reputable than a college newspaper put out by comparatively inexperienced students. A website that is maintained by a well- known, respected organization and regularly updated is more reputable than one created by an unknown author or group.

Whenever you consult a source, always think carefully about the author’s or authors’ purpose in presenting the information. Few sources present facts completely objectively. In some cases, the source’s content and tone are significantly influenced by biases or hidden agendas. Bias refers to favoritism or prejudice toward a particular person or group. For instance, an author may be biased against a certain political party and present information in a way that subtly—or not so subtly—makes that organization look bad. Bias can lead an author to present facts selectively, edit quotations to misrepresent someone’s words, and distort information. Hidden agendas are goals that are not immediately obvious but influence how an author presents the facts. For instance, an article about the role of beef in a healthy diet would be questionable if it were written by a representative of the beef industry—or by the president of an animal- rights organization. In both cases, the author would likely have a hidden agenda.

As Jorge conducted his research, he read several research studies in which scientists found significant benefits to following a low-carbohydrate diet. He also noticed that many studies were sponsored by a foundation associated with the author of a popular series of low-carbohydrate diet books. Jorge read these studies with a critical eye, knowing that a hidden agenda might be shaping the researchers’ conclusions.

In sum, to evaluate a source, you should consider not only how current the source is but also criteria such as the type of source, its intended purpose and audience, the author’s (or authors’) qualifications, the publication’s reputation, any indications of bias or hidden agendas, and the overall professionalism of the source’s language, ideas, and design. You should consider these criteria as well as your overall impressions of sources’ quality. Read carefully, and notice how well authors present and support their statements. Stay actively engaged—do not simply accept sources’ words as truth.

Examples

Writing at Work

The critical thinking skills you use to evaluate research sources as a student are equally valuable when you conduct research on the job. If you follow certain periodicals or websites, you have probably identified publications that consistently provide reliable information. Reading blogs and online discussion groups is a great way to identify new trends and hot topics in a particular field, but these sources should not be your final sources if you’re doing substantial research.

EXERCISE 12

Choose a source you found that you think is relevant but you’re unsure if it’s reliable. Answer the following questions about the source:

- Can you establish that the author is credible and the publication is reputable?

- Does the author support ideas with specific facts and details that are carefully documented? Is the source of the author’s information clear? When you use secondary sources, look for sources that are not too removed from primary research.

- Does the author leave out any information that you would expect to see in a discussion of this topic?

- Does the source include any factual errors or instances of faulty logic?

- Do the author’s conclusions logically follow from the evidence that is presented? Can you see how the author gets to one point from another?

- Is the writing clear and free from errors, cliches, and empty buzzwords?

- Is the tone objective, balanced, and reasonable? Does the source convey any biases? Be on the lookout for extreme, emotionally-charged language.

- Based on what you know about the author, is he or she likely to have any hidden agendas?

- Is the source’s design professional? Are graphics informative, useful, and easy to understand? If the source is a website, is it well-organized, easy to navigate, and free of clutter like flashing ads and unnecessary sound effects?

- Is the source contradicted by information you found in other sources? If so, it is possible that your sources are presenting similar information but taking different perspectives, which requires you to think carefully about which sources you find more convincing and why. Be suspicious, however, of any source that presents facts you cannot confirm elsewhere.

Keeping Track of Sources

As you determine which sources you will rely on most, it is important to establish a system for keeping track of your sources and taking notes. There are several ways to go about it, and no one system is necessarily superior. Here’s what matters: you keep materials in order; record bibliographical information you will need later; and take detailed, organized notes.

Think ahead to a moment a few weeks from now, when you’ve written your research paper and are almost ready to submit it for a grade. There is just one task left—writing your list of sources. As you begin typing your list, you realize you need to include the publication information for a book you cited frequently. Unfortunately, you already returned it to the library several days ago. You do not remember the URLs for some of the websites you used or the dates you accessed them—information that also must be included in your bibliography. With a sinking feeling, you realize that finding this information and preparing your bibliography will require hours of work.

This stressful scenario can be avoided. Taking time to organize source information now will ensure that you are not scrambling to find it at the last minute. Throughout your research, record bibliographical information for each source as soon as you begin using it. You may use pen-and-paper methods, such as a notebook or note cards, or maintain an electronic list. (If you prefer the latter option, many office software packages include separate programs for recording bibliographic information.) The following table shows the specific details you should record for commonly used source types. Use these details to develop a working bibliography—a preliminary list of sources that you will later use to develop the references section of your paper. It will save you time later on to record, from the start, all information you will need about your sources to create a Works Cited page. The following lists what you should record for some common types of sources. Your research may involve other types of sources not listed below. For more information on formatting citations,consult the MLA Guide on the Purdue University Online Writing Lab website at http://owl.english.purdue.edu.

- Book: the author(s), title, subtitle, publisher, city of publication, and year of publication.

- Work (e.g., article) in an anthology (i.e., book): the work’s author(s), title, and subtitle; the book’s title, subtitle, editor(s); any edition and volume numbers of the book; the book’s publisher, city of publication, and year of publication; the pages on which the work appears in the book.

- Periodical: the author(s), title of the article, title of the publication, date of publication, volume and issue number, and range of page numbers of the article.

- Online source: the author(s); the title of the work or web page; the title of the website; the organization that sponsors the website; the database name; the date of publication or date of last update; the date you accessed the source.

- Interview: the name of the person interviewed; the method of communication (e.g., in-person, video chat, email, or phone call); the date of the interview.

As you conduct research, you may wish to record additional details, such as a book’s call number, the contact information for a person you interviewed, or the URL of an online source. That will make it easier for you to quickly locate the source again. You may also wish to assign each source a code (e.g., a number, letter, symbol, or color) to use when taking notes.

Taking Notes Efficiently

Writers sometimes get caught up in taking extensive notes, so much so that they lose sight of how their sources help them to answer their research questions. The challenge is to stay focused and organized as you gather information from sources. Before you begin taking notes, take a moment to step back and remind yourself of your goal as a researcher: to find information that will help you answer your research questions. That goal will determine what information you record and how you organize it. When you write your paper, you will present your conclusions about the topic supported by research. Therefore, you do not need to write down every detail of your sources; some of the information in relevant sources will be irrelevant to your research questions.

There are several formats you can use to take notes. No technique is necessarily better than the others—it is more important to choose a format you are comfortable using. Choose a note-taking method from among those listed below that works best for you, and use it as you gather sources. Using the techniques discussed in this section will prepare you for the next step in writing your research paper: organizing and synthesizing the information you find.

- Use index cards. This traditional format involves writing each note on a separate index card. It takes more time than copying and pasting into an electronic document, which encourages you to be selective in choosing which ideas to record. Recording notes on separate cards makes it easy to later organize your notes according to major topics. Some writers color-code their cards to make them still more organized.

- Maintain a research notebook. Instead of using index cards or electronic note cards, you may wish to keep a notebook or electronic folder, allotting a few pages (or one file) for each of your sources. This method makes it easy to create a separate column or section of the document where you add your responses to the information you encounter in your research.

- Annotate your sources. This method involves making handwritten notes in the margins of sources that you have printed or photocopied. If using electronic sources, you can make comments within the source document. For example, you might add comment boxes to a PDF version of an article. This method works best for experienced researchers who have already thought a great deal about the topic because it can be difficult to organize your notes later when starting your draft.

- Use note-taking software. There are many options for taking and organizing notes electronically. These include word-processing software that you can use offline on a computer. They also include tools like Diigo, Evernote, and Mindomo, available on the Web for free or reduced prices if you will use the tool for educational purposes. Although you may need to set aside time to learn how to use them, digital tools offer you possibilities that handwritten note cards do not, such as searching your notes, copying and pasting your notes into your paper, and saving and sharing your notes online.

Whether you use old-fashioned index cards or organize your notes digitally, you should keep all your notes in one place, and use topic headings to group related details. Doing so will help you identify connections among different sources. It will also help you make connections between your notes and the research questions and subtopics you identified earlier. Throughout the process of taking notes, be scrupulous about making sure you have correctly attributed each idea or piece of information to its source. Always include source information or use a code system (e.g., numbers, letters, symbols, or colors) so you know exactly which claims or evidence came from which sources.

Effective researchers make choices about which types of notes are most appropriate for their purpose. Your notes may fall into three categories:

- Summary notes sum up the main ideas in a source in a few sentences or a short paragraph. A summary is considerably shorter than the original text and captures only the major ideas. Use summary notes when you do not need to record specific details but you intend to refer to broad concepts the author discusses.

- Paraphrased notes restate a fact or idea from a source using your own words and sentence structure.

- Direct quotations use the exact wording used by the original source and enclose the quoted material in quotation marks. It is a good strategy to copy direct quotations when an author expresses an idea in an especially lively or memorable way. However, do not rely exclusively on direct quotations in your note taking.