7: Principles of Sequencing and Rhetorical Organisation - Discourse and Text

- Page ID

- 17863

7. Principles of Sequencing and Rhetorical Organisation: Discourse and Text

In this chapter we consider whether the principles of rhetorical organisation we have identified so far also operate at the levels of discourse and text. We first discuss some data collected by Young (Crosstalk; “Unraveling”), as these provide nice examples of the use of Chinese frame-main sequencing at the level of discourse and which is consequently misinterpreted by an American speaker, leading to a breakdown in communication. We then consider and analyse three examples of extended Chinese discourse and text.

Young relies primarily, but not exclusively, on data gained by recording Chinese speakers engaged in discussions in English and often in role play situations. She makes several judgements about the characteristics of Chinese discourse based on the data. She suggests that the use of the pair of connectors “because” and “so,” that occur frequently in the data, appears to play an important role in discourse sequencing management. They signal, Young suggests, the topic-comment relationship working at the level of discourse. “Connective pairs such as ‘because/as’ and ‘so/therefore’ signal a topic-comment relationship between the ideas or events that they tie together” (“Unraveling” 161). She also suggests that these two connectors operate the whole-part principle. However, in arguing that “because” and “so” signal transition in the phases of argument she says: “The choice of ‘because/as’ to mark the introduction of one’s case and ‘so/therefore’ to indicate a shift to the main point are examples of such transition markers” (150).

Here again topic is being used to describe two different concepts. On the one hand, the “because” connector is said to signal a topic and the whole, while the “so” connector is said to signal the comment and the part. On other hand, the “because” connector is said to signal the introduction of one’s case and the “so” marker signals the transition to the main point. In other words, the “because” connector is claimed to be signalling these three items: the topic; the whole of a whole-part relationship; and the introduction of one’s case. We have seen earlier that the whole of a whole-part relationship can be classified as topic (see example [5] in the previous chapter). But it seems that the “because” connector that signals the introduction to one’s case can only be signalling a topic, if topic is defined as something that sets the framework in which the rest of the sentence is presented. We propose, therefore, that the “because” connector that introduces one’s case is not signalling a topic but is signalling modifying or subordinate information from which the proposition in the principal clause can be understood, signalled by the “so” connector. In other words, it is signaling what we have earlier called a “frame-main” sequence.

We now consider some of Young’s data and examine whether the “because” markers are indeed signalling topics or whether they are signalling subordinate information; and whether the “so” markers are signalling comments or a transition to the main point. Is the sequence one of subordinate/modifier to main/modified rather than one of topic-comment? The data here “comes from an audiotaped role play enacted in Hong Kong as part of a classroom discussion among members of Hong Kong’s police force” (190ff). There are five participants in the role play, one of whom is a white male, a guest speaker to the classroom from the United States. He plays a member of the public. The police, working in pairs, have the task of stopping the American from approaching and going into his office because there has just been a fire in the building. Below are some excerpts.

1(a). American: What’s the matter? This is my office.

Chinese: Oh, because this on fire and this area is closed.

1(b). American: Well, can you—can you call the other officer? You call the other officer and tell him that I have to get into my office. Can you do that?

Chinese: I’m afraid I can’t do it. I’m afraid....

Chinese: Or... or we suggest you uh.... Because it is by the court order closed it, Close it by court order.

1(c). American: But uh I have to find out what happened to my office. Uh, I—I’ve got to get in there.

Chinese: Uh, I’m sorry uh because this cl—this building is closed by court order uh I can’t help you.

1(d). American: But why... why can’t... I just want to go into my office. I have some important papers there.

Chinese: I’m sorry. Because the building is in a dangerous

American: Well...

Chinese: Nobody allowed to enter the building.

In her analysis of the data, Young suggests that the Chinese police officers are transferring their native discourse patterns into English. While this is certainly true, it is hard to argue that the utterances of the Chinese police are following a topic-comment structure when topic is defined as what the sentence is about. What all these “because” initial clauses are doing is setting a framework within which to present the main point the sentence or the principal clause of the sentence. Each of these “because” sentences provides information that will help to explain the information in the principal clause. The information presented by the Chinese police follows, therefore, a sequence that moves from subordinate to main or from frame to main. Thus they follow the principles of logical or natural rhetorical organisation identified earlier. What appears to be confusing the American is that he is expecting the information to follow a sequence which he is more familiar with in this context and which would be from main to subordinate. He is expecting a salient order in which the main or most important part of the message is presented first. In other words, the American might have been more prepared to accept what the police were saying had they sequenced their information in the following way, where the “because” clauses is placed after the main clause:

Chinese: This area is closed because there has been a fire

Chinese: (You can’t go in I’m afraid) because the building is closed by court order.

Chinese: I’m sorry I can’t help you because this building is closed by court order.

Chinese: I’m sorry, nobody is allowed to enter the building because the building is in a dangerous condition.

So, while we agree with Young’s analysis of this interaction that the Chinese police are transferring their native discourse patterns to English, it is suggested that these discourse patterns are not those of topic-comment. Rather the discourse pattern being followed adheres to a subordinate /frame-main or modifying-modified information sequence. This “frame-main” or “because-therefore” sequence adheres to the fundamental principle of logical and natural sequencing in Chinese. We now demonstrate this with examples taken from naturally occurring Chinese discourse and text.

The three pieces of data to be analysed represent one relatively informal occasion (a university seminar) a more formal occasion (a press conference given by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs)18 and a text from the author Lu Xun. The first example comes from the question and answer session which took place after the speaker had given a seminar at a well-known Australian university. The speaker would have not known what sort of questions he would be asked and had no time to plan his answers. This then represents an informal unplanned occasion. We include this, however, as the rhetorical organisation of the discourse follows the principles we have identified, even though it is informal and unplanned. The second piece of data is taken from a Foreign Affairs press conference. While this text was delivered orally, it was planned and pre-written. It is thus a written text delivered orally in a relatively formal setting. The third example comes from an essay written by possibly the most famous Chinese writer of the early twentieth century, Lu Xun.

The university seminar

This was delivered in Modern Standard Chinese by a native speaker from Mainland China, and was entitled “The Peking Student Movement of 1989. A Bystander’s View.” The talk was attended by some thirty people. Although some of those who attended were not native Chinese speakers, all present were able to speak MSC and the entire proceedings—the talk and the question and answer session that followed it—were conducted in MSC. As indicated above, the atmosphere was informal. The speaker was not acting in any official capacity and was certainly not there to give the official line of the events of June 4th (the Tiananmen Massacre). Furthermore, the speaker had personal friends in the audience. Although a long time resident of Beijing, the speaker was living in Australia at the time of the seminar in Australia and has an Australian wife.

We here analyse the question and answer session rather than the talk itself, as the question and answer session was spontaneous in the sense that the speaker had no foreknowledge of any of the questions that he was asked. The speaker’s answers therefore provided good examples of unplanned spontaneous spoken discourse. As explained earlier, we include this because, despite its spontaneous and informal nature, it still follows the fundamental principles of rhetorical organisation.

The first extract is taken from the speaker’s answer to a question asking whether the Chinese students welcomed foreign participation in the Chinese student movement. This has been chosen because it shows a “because-therefore” sequence operating at sentence level. But as we shall see in the analysis of a second extract taken from this answer, this sentence level “because-therefore” sequence can itself be part of a piece of discourse whose overall sequence is also “because-therefore,” or what we are calling the “frame-main” pattern. The first excerpt occurs thirteen lines into the answer dealing with foreign involvement in the June 4th “incident.” In the previous twelve lines, the speaker has pointed out that some students were in favour of foreign involvement and that others were against it. He has raised the legal question but has also said that the law is a “fascist” one. He then says:

2.because (yinwei) we haven’t faced this question, I and my wife both have Beijing residence permits, therefore (suoyi) I haven’t more thoroughly investigated this problem.

The speaker explains that he has not thought very much about the question of foreign participation in the student movement because he and his wife are not foreigners. (Actually his wife is an Australian but, as he explains, she has a Beijing residence permit, so, for the purposes of the question presumably doesn’t count as a foreigner). Note that “I and my wife both have Beijing residence permits” is itself a reason for why they have not faced the question of foreign participation. The suoyi is linking with the yinwei in line one of the example and is separated from it by the secondary reason. This shows that suoyi can refer back to reasons separated from it by other information. As we shall show, suoyi often operates as a discourse marker across lengthy texts. Note also that the information sequence follows the “because-therefore” sequence, and that the subordinate-main clause sequence is operating here at a level above the clause. This information sequence, with its overt and covert discourse markers, can be represented as:

Sequence Connectors

Reason yinwei

Reason for reason no overt marker

Therefore suoyi

The second extract, (3), comes from this same answer. It demonstrates a more complex information sequence that includes what we call a “pregnant” “because-therefore” unit, which incorporates, among others, a concessional structure and lower level “because-therefore” structures. Where connectors in the translation are placed in brackets, it signifies that they are not present in the Chinese.

3.but because I N meet this question, although I-M, wife be Australia person, but she then in China have, Beijing permit, therefore she can-P for example even with parade troops walk one walk, because she have Beijing citizen status this we N enter one step discuss I N way again deep reply sorry-A.

but because I haven’t come across this question, (because) although my wife is Australian she had in China at the time a Beijing residence permit therefore she might for example even walk with the parading marchers because she has Beijing citizen status (so) we haven’t further discussed this (so) I have no way in replying in any more depth, sorry.

The pregnant “because-therefore” unit starts with the “because” (yinwei), in line 1. The “this question” that the speaker mentions is the original question concerning foreign participation in the Chinese student movement. The “therefore” part of this “because” is not stated until later. That is to say, because the speaker and his wife haven’t come across the question, (so) they haven’t discussed it, and (so) the speaker cannot give an in-depth reply to the question. The reader will notice that there are no overt connectors introducing the “therefore” part of the discourse unit. The translation provides (so) in brackets.

Within this pregnant “because-therefore” unit lie:

(i)a concessional although (suiran)-but (danshi), construction. This follows the normal unmarked sequence of subordinate clause-main clause. The pair of connectors, suiran and danshi are both present.

(ii)The therefore (suoyi) represents the “therefore” part of a “because-therefore” sentence level construction. The yinwei, which could be placed either before or after the suiran, is not present. We have inserted (because) in the English translation. Notice how the “because” is restated later. The marked MC-SC sequence is used here as the speaker is emphasising the importance of his wife’s Beijing residence status and citizenship.

(iii)a “for example” clause that is in parenthesis within the suoyi clause

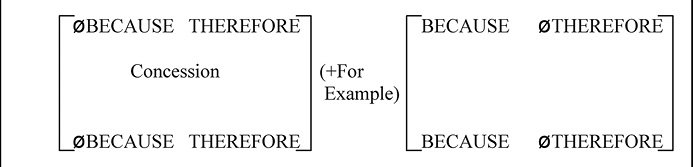

These few lines of data provide a complex rhetorical structure and sequence that is presented as Figure 1, below.

Figure 1. Complex rhetorical structure and sequence.

What this shows is that the discourse “because-therefore” or “frame-main” sequence can include within it, at lower levels of textual hierarchy, a complex of other propositions, among which can be lower level “because-therefore” relations. That is to say, the sequence can be realised at any level and that the lower level units can lie within the pregnant unit. Figure 1 also shows that (3) is characterised by what we shall call enveloping. This provides a clue that the answer is unplanned as enveloping often signals spontaneous speech. Enveloping is common in speech where a speaker’s turn is determined only immediately prior to his turn, and the speech is, therefore, unplanned. Sacks, et al., also state a significant corollary of this, which is that a planned or pre- allocated turn will contain a “multiplication of sentence units” (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson 730). Data from the more formal press conference should therefore provide more examples of coordinate structures with relatively few overt connectors.

“Because” connector yinwei as a discourse marker

The “because” connector yinwei can act as a discourse marker. In (4) below, another example taken from the university seminar, the “because” connector controls a series of reasons that precede the “so” summary statement. Here, the speaker is answering the question “Why are you a bystander and not a playmaker?” The speaker initially responds by laughing and saying that, “this is a very good question.” It is possible that he feels a little defensive about this as it would have been possible to infer that the questioner is disapproving of the speaker’s role of mere bystander. As a result, the speaker feels that he is being called upon to justify his role.

He then says that there are, “two reasons..., two points, the first:”:

4.because-P, I-P at middle school period-P, be at that, China also good world also good-P, then little red guards source-M in growing up-M students, I then read middle school-M time already then see-EXP armed struggle also participate-EXP small scale-M armed struggle, I also that time already also in rifle in tank under live-EXP, I have-EXP that kind one-M life experience, I perhaps NOM some things special some things see-R-trivial-P little, this one ques(tion)

(the first point,)

because, at the time I was at middle school, China was fine, the world was fine, the little red guards started, and students growing up, when I was at middle school I had already seen armed struggle and had taken part in small scale armed struggle, and also at that time I had lived with guns and tanks, I have had that experience of life, (so) I possibly trivialize things a little, that’s one question.

In answer to the question of why he is a bystander and not a playmaker, the speaker says that there are two points to bear in mind. Example (4) gives his account of the first point which consists of a series of reasons why the speaker tends to trivialise things (and thus is content to be a bystander at the current time rather than a playmaker). The “because” connector yinwei controls a whole series of reasons. There is no overt discourse marker here that signals the start of the summary “so” statement. The rhetorical structure and sequence of (4) can therefore be represented as follows:

Because n (where n means any number of reasons)

Therefore

Having stated the first reason for why he is a bystander and not a playmaker, the speaker goes on to provide the second reason. His basic point is that he did not say that he was going to tell all in his talk, the inference being that he perhaps did play some active role, although he did not mention it in his talk. Having said this he comments:

5.therefore-P (suoyi) this question who knows I myself and other people-M one one question, thus (yinci) I N participate this these student movement-M any protest activity

therefore this question, who knows, is a question for myself and other people, (and) so I didn’t take part in this, in any of these student protest movements….

In (5) the speaker first provides the summary statement for his second reason for being a bystander. This is signalled by the use of the therefore marker suoyi. He then goes on to provide the summary statement of his entire answer to the question “Why are you a bystander and not a playmaker?” This, in turn, is signalled by another therefore marker yinci.

What this shows is a recursive information sequencing pattern of “because-therefore” occurring throughout the answer. This also prefaces the final summary “therefore.” The speaker, in attempting to justify his role as a mere bystander, uses the “because-therefore” sequence at several levels of hierarchy, thus following a justification for statement-statement pattern in the form of a “frame-main” sequence.

“Therefore” connector suoyi as a signaller of a summary statement

The use of discourse marker “therefore” to signal the summary statement of an entire piece of discourse rather than the immediately preceding argument(s) can also be seen in (6) and (7) below. For (6), the speaker has been answering a question concerning the power of dialogue in the present situation in China. The questioner wants to know whether the speaker thinks that dialogue has a chance of success in the Chinese political climate of the time. In a long answer running to more than thirty lines of tapescript, the speaker cites several reasons why he thinks that dialogue has little chance of success in China at the moment. The main reason he gives is that, for dialogue to succeed, there has to be a workable balance of power between the parties. He cites several historical examples to back this up. He then ends his answer by saying:

6.now thus (yinci) I not think these dialogue can succeed because not exist one equal dialogue-M base is this way

thus I don’t think that these dialogues can succeed because an equal base for dialogue doesn’t exist, that’s the way it is.

Here, the “therefore” marker yinci is signalling the summary statement for the whole answer and its communicative purpose is to let the audience know that the answer is coming to a close. Interestingly, it is coupled with a “because” clause in the marked sequence of main clause-subordinate clause. The speaker has included this final because clause to emphasise the main point of the argument he has been making throughout the answer. He feels the point is of sufficient import to be restated and to be marked in this way. In general, however, the speaker’s answer here provides another example of reasons preceding the statement, or of grounds preceding the claim and “frame-main.”

The final piece of this seminar data (7) represents the closing words of the speaker’s final answer. Here the “therefore” connector suoyi is being used to signal the summary statement, not just of the answer that the speaker has been giving, but of the entire session. Remember that the talk was entitled “The Beijing Student Movement of 1989. A Bystander’s view.”

7.this I therefore (suoyi) be bystander, this this say—this way, anybody anybody still have what this, therefore I’m a bystander, all this I’ve said is (about) this.

And that’s why I’m a bystander. Does anyone have anything else?

That nobody does raise a further question and the chairman of the meeting then calls the meeting to a close, suggests that the audience recognised the speaker’s final summary statement for what it was.

This analysis of the university seminar has shown:

(i)that the “because-therefore” sequence is a common way of sequencing information at the level of discourse. This means, for example, that the speaker often precedes a statement or claim with the grounds for that statement or claim and thus follows a rhetorical structure of a “frame-main” sequence;

(ii)that enveloping occurs with unplanned speech and that a “because-therefore” unit can therefore act as a “pregnant” unit containing a number of lower level units;

(iii)that the connector yinwei can function as a discourse marker, where it signals or controls a number of reasons; it need not be lexically marked;

(iv)that the connector suoyi can signal a summary statement. On occasion when performing a summarising function, it need not be lexically marked.

The Taiwan Airlink Press Conference

The second piece of extended discourse to be analysed comes from a press conference held in Beijing. This data represents a planned piece, as the spokesman reads from a prepared written text before inviting questions from the assembled journalists. The press conference starts with the spokesman welcoming the journalists and then saying that he has several items of news that he wishes to impart before answering their questions. The third item of news concerns a proposed Soviet-Taiwan airlink. This is a topic that had occasioned some speculation (the press conference was held in 1990), and the aim of the spokesman is to quell the speculation by placing on record China’s official position. Excerpt (8) below is the translator’s version of the statement which was read out by the spokesman.

8.My answer to this question is it is our consistent policy that Taiwan is a part of the territory, China, and one of its provinces. We are resolutely opposed to the establishment of official relations or official contacts with Taiwan by countries which have diplomatic relations with China. To start an air service with Taiwan by any foreign air company. Governmental or non-governmental is by no means non-governmental economic and trade relations in an ordinary sense but rather a political issue involving China’s sovereignty. Therefore consultation with China is a must before such a decision is taken. We hope that the countries will act with prudence on this matter.

These comments follow the by now familiar “because-therefore” and “frame-main” sequence, although, as predicted for planned discourse which follows the unmarked MC-SC sequence, there are no overt “because” markers in the text. Interestingly, in the original Chinese, the spokesman does not use an overt “therefore” marker either to signal the overall summary of the statement, only adding this when the interpreter fails to translate the final comment about the need for consultation. The spokesman actually repeats his final comment, adding the therefore marker in the way shown in (9) below.

9.Bixu dou bixu shixian yu wo shangliang

Must all must first with me discuss

(The interpreter fails to translate this in the first instance, so the spokesman repeats it, but, tellingly now also adds a “therefore” marker to explicitly signal that this is the conclusion of the statement.)

Suoyi dou bixu shixian yu wo shangliang

Therefore all must first with me discuss

Therefore consultation with China is a must before such a decision is taken.

For good measure he then adds:

Xiwang you guan guojia zai zhe shi-shang shenzhong xingshi

Hope have concern country in this matter-on prudent conduct.

We hope that the countries will act with prudence on this matter.

The spokesman’s comments follow this rhetorical structure.

Because therefore

Taiwan is a part of China oppose others dealing with Taiwan

opening an airlink with China must be consulted and

Taiwan is political people must act prudently

The lack of any “because” or “therefore” discourse markers is evidence that these comments were prepared beforehand. Interestingly, they proved to contain too much information for the interpreter to manage, so the spokesman had to repeat his final point and added an explicit “therefore” in order to underline the argument.

The third example we analyse is taken from Wu Yingtian who provides it as an example of inductive reasoning. Wu (124) defines inductive reasoning as follows:

The organisation of induction always places the material first, discusses the argument (liyou), and then puts forward the conclusion, making the thesis unequivocally clear.

To exemplify inductive reasoning, Wu uses this summary of a contemporary essay by Lu Xun in which he compares Hitler with the Qin emperor, Qin Shihuang (124ff).

Xitele gen Qin Shihuang bi shi diji-de

Hitler and Qin Shihuang than be low-M

Xitele gen Qin Shihuang bi shi kechi-de

Hitler and Qin Shihuang than be shameful-M

Xitele gen Qin Shihuang bi shi geng duanming-de

Hitler and Qin Shihuang than be even short-lived-M

(er, diji, kechi, duanming shi kebei-de)

(and low, shameful, short-lived is lamentable)

Suoyi (Xitele bi Qin Shihuang shi kebei-de)

Therefore (Hitler than Qin Shihuang be lamentable-M)

raner Xitele zai Zhongguo-de ganr-men dou wei

but Hitler in China-M follower-PI all for

Xitele shang tai er xinggao cailie

Hitler gain power as happy delirious

Suoyi Xitele zai Zhongguo-de ganr-men

Therefore, Hitler in China-M followers-PI

shi gaoxing-de tai zao-le

be happy-R too soon-A

Hitler was of a lower status than Qin Shihuang. He was more shameful and he didn’t even live as long as Qin Shihuang. (Now) being of low status, shameful and short lived is tragic and therefore Hitler was a more tragic figure than Qin Shihuang. Yet Hitler’s followers in China were deliriously happy at his accession to power. They were therefore happy too soon.

The reasoning here runs that because Hitler is lower, more shameful and short lived (historically) than Qin Shihuang (the first emperor of China), he is therefore more pitiful. But because Hitler’s followers in China were deliriously happy when Hitler assumed power, their happiness was therefore premature.

What is of interest here is that the reasons precede the conclusion and the argument follows a “because-therefore” or “frame-main” sequence. We can represent this piece of inductive reasoning in the following way:

Inductive Reasoning

Individual Arguments (fenlun)

Ø BECAUSE 1

Ø BECAUSE 2

Ø BECAUSE 3

Ø BECAUSE 4 THEREFORE

Ø BECAUSE 5 THEREFORE

This can be summarised as:

Ø BECAUSE 1-4 — THEREFORE

Ø BECAUSE 5 — THEREFORE

This provides a further example of inductive reasoning in contemporary Chinese. The “because-therefore” sequence is followed and its propositional structure is similar to the propositional structures of the discourse and text presented above and in earlier chapters.

The next question is, therefore, whether inductive reasoning is common in Chinese and whether Chinese prefers to use inductive reasoning over deductive reasoning. In Chapter 2, we showed that Chinese traditionally used chain-reasoning and reasoning by analogy and historical precedent in preference to hypothetico-deductive reasoning. We have also seen that the propositional structures of arguments following these methods of reasoning have many similarities to the propositional structures of the examples of extended discourse and text analysed here. The argument here is that chain-reasoning is very similar in its propositional structure to inductive reasoning and we would thus expect Chinese to show a preference for inductive reasoning. As Sivin has pointed out, rational thought can be either inductive or deductive or a combination of both. In contrast to this flexibility, however, we argue that chain-reasoning, by its very nature, can only be inductive. It can never be deductive, using, as it does, a number of examples or pieces of information to establish a generalisation or conclusion. In its preference for chain-reasoning and reasoning by analogy and historical precedent, Chinese exhibits a consonant preference for inductive reasoning.

Before concluding this chapter we want to again stress that this preference for inductive reasoning does not imply that Chinese does not employ other types of reasoning. Indeed, in Chapter 2, we showed that Wang Chong, the Han dynasty scholar, used deductive reasoning when his aim was to make a controversial point and draw the attention of the audience and, in Chapter 3, we showed Chen Kui’s support for a deductive sequence.

Wu also provides examples of what he calls yangui xing, which is simply a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning. This is interesting and, as we shall see in Chapter 8, Wang (108–9) also provides evidence for this type of combined reasoning in the paragraph organisation of Chinese writers and this confirms the point made by Sivin above concerning the organisation of rational thought. Wu (130) represents this type of reasoning in the following way:

Inductive-Deductive Reasoning (yangui xing)

1 General statement (zonglun)

2 Individual arguments (fenlun)

Conclusion (jielun)

In his summing up of methods of reasoning and textual organisation in Chinese, Wu concludes, using a typical “because-therefore” sequence (135), “Because in real life cause precedes effect, therefore to place the reason at the front (of the argument) also accords with logic.”

This statement nicely encapsulates the main point we have been making, which is that Chinese prefers to follow this frame-main or because-therefore sequence in a wide range of texts, from the sentence level through complex clauses and to the level of discourse and text. This principle of rhetorical organisation is fundamental to Chinese rhetoric and writing, although it by no means excludes other types of rhetorical organisation.

Summary

The following principles of rhetorical organisation have been identified and illustrated in this chapter.

(i)The “because-therefore” sequence operates at levels of discourse as well as at sentence level. It represents an important sequencing principle in MSC. For example, when MSC speakers are justifying a claim, they commonly posit the reasons for the claim before making it, following a “frame-main” sequence.

(ii)The “because-therefore” sequence can be recursive. This rhetorical structure is more likely to occur in planned speech than in spontaneous speech. Although, in more planned speech, the use of the because and therefore connectors is comparatively uncommon, a therefore connector, either suoyi or yinci is common, but not obligatory, when its communicative purpose is to signal a summary statement.

This rhetorical structure is represented in the diagram.

BECAUSE x n +THEREFORE x n

THEREFORE.

(iii)In more spontaneous speech, enveloping is likely. When this occurs a “because-therefore” unit can act as a “pregnant” unit and contain a number of lower level units within it. These lower level units can themselves be lower level “because-therefore” units. In more spontaneous speech, where there is enveloping, connectors are more common. This structure is represented in the diagram.

BECAUSE [LOWER LEVEL UNITS] THEREFORE

(iv)The structures in (ii) and (iii) can be used in combination.

(v)In addition to acting as sentence level connectors, both the “because” and the “therefore” connectors can act as discourse markers. They can introduce and control a series so that “because x n” and “therefore x n” are possible sequences.

(vi)The presence of explicit “because” and “therefore” discourse markers is less likely in formal planned speech than in informal and more unplanned discourse.

To date, we have suggested that Chinese traditionally followed a logical or natural order and that this is a fundamental principle of rhetorical organisation in Chinese. This logical order is contrasted with the preference English shows for salient ordering, where the important part of the message is presented early. This principle results in Chinese preferring sequences such as topic-comment, whole-part, big-small, modifier-modified, subordinate–main, and frame-main. We have called these the unmarked or preferred sequences in Chinese. This is not to say, however, that classical Chinese did not allow marked sequences in certain circumstances. A significant increase in the use of marked sequences, such as main–subordinate in modern Chinese is, nevertheless, largely the result of the influence upon Chinese of the rhetorical organisation and clause structure present in Western languages.

We have also argued that the rhetorical “frame-main” structure and sequence which we have identified at the clause, sentence levels also operates at the level of discourse and extended discourse, as illustrated in the examples above. We further propose that this “frame-main” principle of rhetorical organisation also shaped the structure of many of the texts of classical and traditional Chinese which were illustrated in earlier chapters.

In the next chapter, we look at the influence of Western rhetoric and writing on Chinese rhetoric and writing at the turn of the twentieth century and describe the historical context in which this influence developed.