11.1: Love and Affection

- Page ID

- 109109

CONTENT WARNINGS

The topic of rape is brought up in the following discussion. Sadly, some formative Roman legends include acts of rape. It’s hard to talk about their idea of love without including their perception of sexuality, and sadly their example of the ideal woman in regard to sexuality was a victim of rape

Learning Objectives

By learning about the Romans’ perception of love and how to display affection, you will understand:

- How upper-class men and women were expected to act in regards to affection and love;

- The situations in which these expectations were not followed and whether or not people would be punished for that;

- The Roman notion of Vir and Virtus and their relevance in the way Roman men could express tenderness.

LOVE, AFFECTION, AND TENDERNESS IN ROMAN CULTURE

This section is focused on love, tenderness and affection in the Roman world. Here we define love and tenderness in Roman society as small acts of affection, kindness, flirtation, and ‘sweetness,’ such as bringing a gift to one’s loved one, a description of what a good parent one was, embracing the one you love, writing a poem about how wonderful your partner is etc. Although there are many examples of moments such as these, it doesn’t mean that the general Roman regard for such actions was positive. The overall conception of acts of affection was negative; for a man to display it was to demonstrate weakness and ‘softness’ and for a woman to display it was to be licentious (sadly slut-shaming has existed for millennia). Both women and men, but especially women, were supposed to uphold pudicitia, a complex virtue that can be translated basically to restraint or chastity. A woman with a high degree of pudicitia was called a univira or ‘one-man woman.” An univera aimed to always appear modest and— this is very important— would limit her social interactions with men who were not her relatives. Livy (59 BCE-17 CE) presented the legendary figure of Lucretia as the epitome of pudicitia, a woman who committed suicide after her rape in order to preserve firstly her husband’s dignity, and then hers. Men, on the other hand were measured by the quality of their virtus. It is an untranslatable word, but it includes the notions of courage, excellence as a soldier, qualities of ‘hardness’ (think Don Draper– super masculine, but not in-your-face masculine like they have to prove it to you) and sexual prowess. So on one hand the Romans were expected to display their chastity and fidelity–no sleeping around–but on the other, men were judged by their sexual prowess. One cannot talk about love without talking about marriage. For the man to spend too much time lounging about his house was to bring dishonour to himself. The woman would be looked down upon if she seemed to be the reason a man was not leaving his household. Essentially, to display affection and tenderness in any way was to defy almost all social convention.

The men on whom I will be focusing–Sulla , Pompey the Great and Catullus –do all of these things, and some people—although, almost all of our sources are from elite men— are frustrated by it. What we might find surprising in regards to Pompey and Sulla is that Romans found themselves at an impasse when judging the two military leaders because, as both were incredibly successful commanders, they were basically the biggest viri[1] (men) in Rome, but by allowing themselves to be overcome by their affection, they were displaying ‘soft’ qualities—things that the Romans found deeply troubling in Roman men.

Despite people’s derision for these actions however, they could not slander Pompey nor Sulla in relation to their military capability. The poet Catullus, on the other hand, was no politician nor military man. He wrote directly from his heart, showing us that the Romans felt emotion, love and heartbreak just as we do, even though they weren’t supposed to express that. As Daisy Dunn explains, Rome’s first lyric poet shocked many in his day as he continues to shock many today…

Catullus’ poems seem so surprising and immediate. While some are learned and erudite, some are mischievous, goatish and direct…one of the reasons Catullus’ poems are still so readable… is that they show that the people of this world were not always so very different from us.

Daisy Dunn, Catullus’ Bedspread, The life of Rome’s Most Erotic Poet (pg.4)

Catullus, Pompey, and Sulla were all similar in one way—They upset the expectations and the conservative sensibilities of the upper-class. They knew what they were doing and they did it anyway. They allowed themselves to directly access their own passion, and allowed it to affect their actions, despite the derision this earned them from members of the Roman upper class.

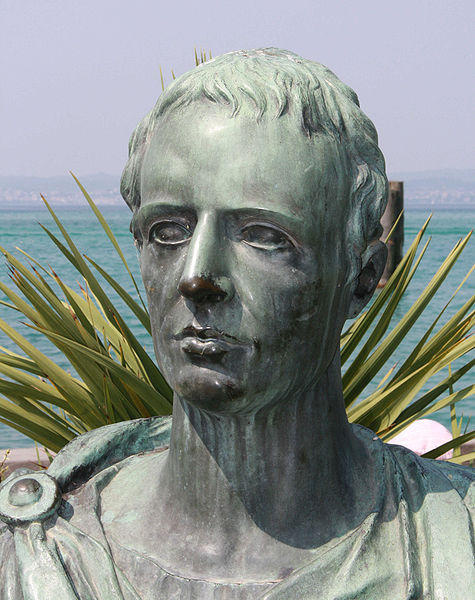

POMPEY

(106-48 BCE)

Pompey is a very interesting case in the topic of love and tenderness; he seems to have been quite an emotional man in general, and got married and divorced several times for political reasons. By Sulla’s command, Pompey divorced his first wife in order to marry Sulla’s daughter, Aemilia Scaura (100– 82 BCE). He was upset by the divorce, but as was the Roman convention for the upper-class, he solidified his alliance with Sulla through the marriage in the year 82 BCE. An exceptional case, however, is the marriage he had with Julius Caesar’s daughter, Julia (76-54 BCE). Although this marriage was the typical, politically-inspired one—arranged to signify the bond between Julius and Pompey in the Triumvirate, the alliance made by Crassus, Pompey, and Julius Caesar in 60 BCE which lasted until 53 BCE— Pompey and Julia seemed to genuinely fall deeply in love with each other. Their marriage occurred in 59 BCE. Pompey even offered the man to whom Julia was currently betrothed, his own daughter in order to marry Julia himself.

However, by his subsequent acts he made it clear that he had now wholly given himself up to do Julius Caesar’s bidding. For to everybody’s surprise he married Julia, the daughter of Caesar, although she was betrothed to Caepio and was going to be married to him within a few days; and to appease the wrath of Caepio, Pompey promised him his own daughter in marriage, although she was already engaged to Faustus the son of [the Dictator] Sulla. Caesar himself married Calpurnia, the daughter of Piso[2]

Plutarch, Life of Pompey 47:5-6

Quite soon, Pompey became incredibly taken with his wife.

However, Pompey himself also soon gave way weakly to his passion for his young wife, devoted himself for the most part to her, spent his time with her in villas and gardens, and neglected what was going on in the forum, so that even Clodius, who was then a tribune of the people, despised him and engaged in the most daring measures.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey: 48:5

As we can see from this source, the Roman regard for such affection is quite negative; men who display it are seen as ‘soft’ and weak.

Furthermore, the political marriage of Pompey and Julia observably becomes more than just ‘political’ as Pompey is speaking with his friends on how to quell some contention the senate held towards him.

To Culleo, however, who urged him to divorce Julia and exchange the friendship of Caesar for that of the senate, he would not listen, but he yielded to the arguments of those who thought he ought to bring Cicero back.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey: 49:3

The upper-class of Rome thinks Pompey is growing weak because he’s spending too much time with his wife, touring around Italy and enjoying themselves. Plutarch is considering the reasons why this young woman was so in love with such an older man, and guesses that it was probably because Pompey was faithful to her and was quite a charming individual. He then records that, although the general public despised his alliance with Caesar, and Julia by extension, they eventually removed her from blame. The event that effectuated this realization was when there was a skirmish at an election one day, Pompey got (someone else’s) blood on his toga. He changed clothes and had his servants bring his bloodied toga home. Julia was horrified when she saw this and fainted, thinking her husband had died. After this, people realized how deep the love that she and Pompey shared was, and they developed a significant respect for her (54 BCE).

All this won him admiration and affection; but on the other hand he incurred a corresponding displeasure, because he handed over his provinces and his armies to legates who were his friends, while he himself spent his time with his wife among the pleasure-places of Italy, going from one to another, either because he loved her, or because she loved him so that he could not bear to leave her; for this reason too is given. Indeed, the fondness of the young woman for her husband was notorious, although the mature age of Pompey did not invite such devotion. The reason for it, however, seems to have lain in the chaste restraint of her husband, who knew only his wedded wife, and in the dignity of his manners, which were not severe, but full of grace, and especially attractive to women, as even Flora the courtesan may be allowed to testify.

It once happened that at an election of aediles people came to blows, and many were killed in the vicinity of Pompey and he was covered with their blood, so that he changed his garments. His servants carried these garments to his house with much confusion and haste, and his young wife, who chanced to be with child, at sight of the blood-stained toga, fainted away and with difficulty regained her senses, and in consequence of the shock and her sufferings, miscarried. Thus it came to pass that even those who found most fault with Pompey’s friendship for Caesar could not blame him for the love he bore his wife. However, she conceived again and gave birth to a female child, but died from the pains of travail, and the child survived her only a few days. Pompey made preparations to bury her body at his Alban villa, but the people took it by force and carried it down to the Campus Martius[3] for burial, more out of pity for the young woman than as a favour to Pompey and Caesar.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 53:1-5

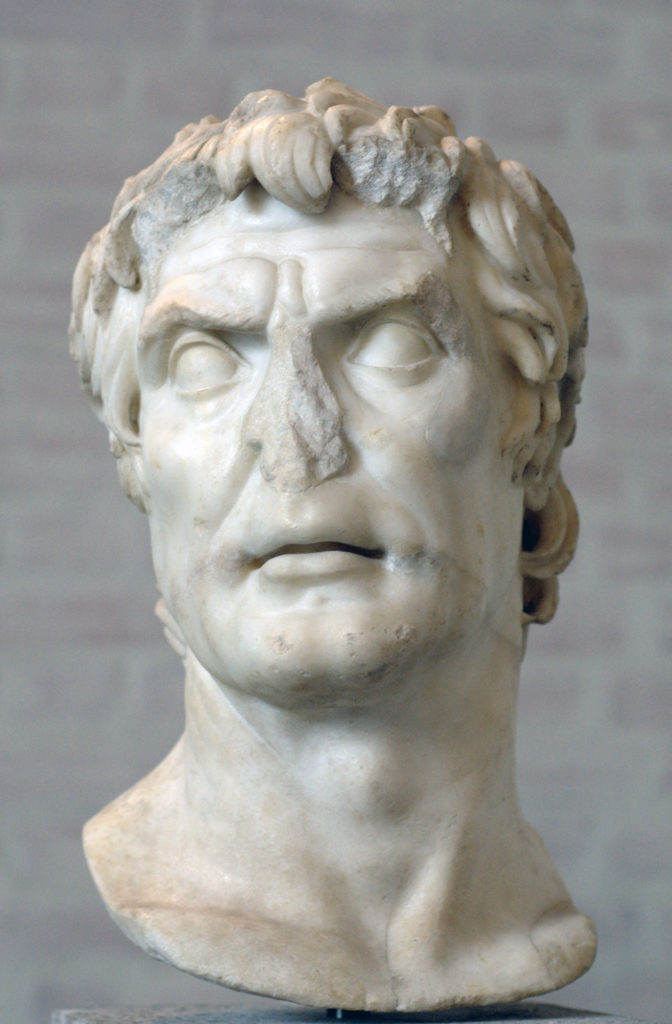

SULLA

(138-78 BCE)

Sulla was ambitious, always seeking to improve his lot in life, to achieve what he wanted to achieve with little to no regard for the traditional Roman hierarchical order. This was tolerated because he was seen as a significant vir. His flirtations with women (as we shall see later) and displaying affection publicly was within his character and likely occurred often because, as we see here, he was not a shy man. In Rome, wasting the money you inherited was looked down upon just as much as rising up in the system from nothing. The latter certainly was the case for Sulla, as a nobleman points out below.

When he was a youth, he lived in lodgings, at a low price, and this was afterwards thrust in his teeth when men thought him unduly prosperous. For instance, we are told that when he was putting on boastful airs after his campaign in Libya, a certain nobleman said to him: “How canst thou be an honest man, when thy father left thee nothing, and yet thou art so rich?”

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 1:1-2

He’s so ambitious that he even named his own children “successful.”

He named the male child Faustus, and the female Fausta; for the Romans call what is auspicious and joyful, “faustum.”

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 34:3

Sulla is able to get away with his ‘frivolities’ with women because he is a vir. Here Sulla enacts his Proscriptions (around 82 BCE): an act he made which would help him eliminate his political enemies without himself having to bear the culpability of murder. He essentially puts bounties on the heads of his enemies. Sulla is able to get away with the most horrendous of deeds, so one can imagine that he was able get away with acts of affection, despite them being looked down upon by the upper class, without repercussion. Furthermore, his proscriptions essentially eliminated all of the powerful people who opposed him, and aligned the rest with him out of fear. This may also be why he felt no need to adhere to the traditional system.

Sulla at once proscribed eighty persons, without communicating with any magistrate; and in spite of the general indignation, after a single day’s interval, he proscribed two hundred and twenty others, and then on the third day, as many more. Referring to these measures in a public harangue, he said that he was proscribing as many as he could remember, and those who now escaped his memory, he would proscribe at a future time. He also proscribed anyone who harboured and saved a proscribed person, making death the punishment for such humanity, without exception of brother, son, or parents, but offering any one who slew a proscribed person two talents as a reward for this murderous deed, even though a slave should slay his master, or a son his father. And what seemed the greatest injustice of all, he took away the civil rights from the sons and grandsons of those who had been proscribed, and confiscated the property of all.

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 31:1-4

The following is an interesting connection between Pompey and Sulla—this is very fascinating if we keep in mind Pompey’s later political marriage with Julius Caesar’s daughter.

[W]hen Sulla had made himself master of Italy and had been proclaimed dictator, he sought to reward the rest of his officers and generals by making them rich and advancing them to office and gratifying without reserve or stint their several requests; but since he admired Pompey for his high qualities and thought him a great help in his administration of affairs, he was anxious to attach him to himself by some sort of a marriage alliance. His wife Metella shared his wishes, and together they persuaded Pompey to divorce Antistia[4] and marry Aemilia[5], the step-daughter of Sulla, whom Metella had borne to Scaurus, and who was living with a husband already and was with child by him at this time.

This marriage was therefore characteristic of a tyranny, and befitted the needs of Sulla rather than the nature and habits of Pompey, Aemilia being given to him in marriage when she was with child by another man, and Antistia being driven away from him in dishonour, and in piteous plight too, since she had lately been deprived of her father because of her husband (for Antistius had been killed in the senate-house because he was thought to be a partisan of Sulla for Pompey’s sake), and her mother, on beholding these indignities, had taken her own life. This calamity was added to the tragedy of that second marriage, and it was not the only one, indeed, since Aemilia had scarcely entered Pompey’s house before she succumbed to the pains of childbirth.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 9:1-2

Perhaps Sulla was sort of a father figure for Pompey, thus Pompey’s inclination to ignore upper-class tradition was amplified by Sulla’s influence on him. Here Sulla gives Pompey political advice, seeming to sort of scold him for making a foolish decision (78 BCE).

And so, when Sulla saw Pompey going away from the polls delighted with his victory, he called him to him, and said: “What a fine victory this is of thine, young man, to elect Lepidus in preference to Catulus[6], the most unstable instead of the best of men! Now, surely, it is high time for thee to be watchful, after strengthening thine adversary against thyself.” And in saying this, Sulla was something of a prophet; for Lepidus speedily waxed insolent and went to war with Pompey and his party.

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 34:5

The following is an important passage for the topic of Love in ancient Rome. It shows us just how far one is able to transgress convention without completely disregarding it. Sulla is having a religious celebration, but his wife, Metella[7] (115-80 BCE) is dying while he does it. Because Sulla was an Augur[8], he had to send her a bill of divorce so her sickness wouldn’t ‘pollute’ his home. He seemed to have felt quite bad about this because after his wife died, he broke his own law which limited the price of funerals by having an incredibly elaborate funeral for her. He also threw many banquets in her honour after her death in which he drank great quantities to drown his sorrows (80 BCE).

On consecrating the tenth of all his substance to Hercules, Sulla feasted the people sumptuously, and his provision for them was so much beyond what was needed that great quantities of meats were daily cast into the river, and wine was drunk that was forty years old and upwards. In the midst of the feasting, which lasted many days, Metella lay sick and dying. And since the priests forbade Sulla to go near her, or to have his house polluted by her funeral, he sent her a bill of divorce, and ordered her to be carried to another house while she was still living. In doing this, he observed the strict letter of the law, out of superstition[9]; but the law limiting the expense of the funeral, which law he had himself introduced, he transgressed, and spared no outlays. 3 He transgressed also his own ordinances limiting the cost of banquets, when he tried to assuage his sorrow by drinking parties and convivial banquets, where extravagance and ribaldry prevailed.

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 35

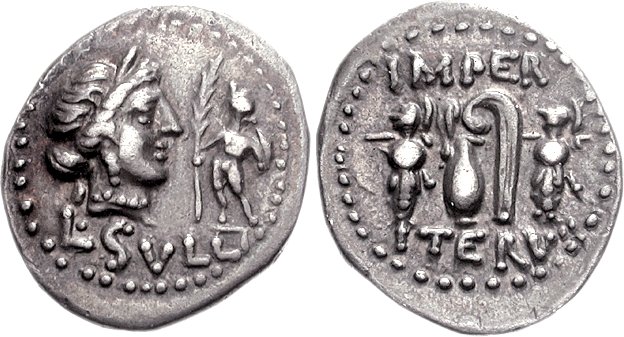

SULLA’s AUGURY COINS

After Metella died, it seems love found its way to Sulla once again, as he flirted with a woman at a gladiatorial game (this was before the reign of Augustus, so men and women were permitted to sit together…perhaps this story is part of the reason why Augustus segregated seating—the upper-class hated what happened between Sulla and this new woman—Valeria).

Valeria (108-78 BCE)[10] flicks some dust off of Sulla’ toga and the two spend the rest of the day sharing playful glances. These acts of flirtation continued for a while and finally led to marriage some time later. Plutarch seems to look down on it because he believes that Sulla was carried away by his attraction and the flirtation that occurred between him an Valeria like a young boy, not a dignified Vir. Perhaps the reasons Sulla acted in such a divergent way from the norm for the upper-class were partly due to the death of his previous wife and partly due to the power he had at this point in life. In the Roman social ladder, there really wasn’t any higher place that Sulla could climb. Maybe he felt he didn’t really have to follow any rules he didn’t like anymore (80 BCE).[11]

A few months afterwards there was a gladiatorial spectacle, and since the places for men and women in the theatre were not yet separated, but still promiscuous, it chanced that there was sitting near Sulla a woman of great beauty and splendid birth; 4 she was a daughter of Messala, a sister of Hortensius the orator, and her name was Valeria, and so it happened that she had recently been divorced from her husband. As she passed along behind Sulla, she rested her hand upon him, plucked off a bit of nap from his mantle, and then proceeded to her own place. When Sulla looked at her in astonishment, she said: “It’s nothing of importance, Dictator, but I too wish to partake a little in thy felicity.” 5 Sulla was not displeased at hearing this, nay, it was at once clear that his fancy was tickled, for he secretly sent and asked her name, and inquired about her family and history. Then followed mutual glances, continual turnings of the face to gaze, interchanges of smiles, and at last a formal compact of marriage. All this was perhaps blameless on her part, but Sulla, even though she was ever so chaste and reputable, did not marry her from any chaste and worthy motive; he was led away, like a young man, by looks and languishing airs[12], through which the most disgraceful and shameless passions are naturally excited.[13]

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 35

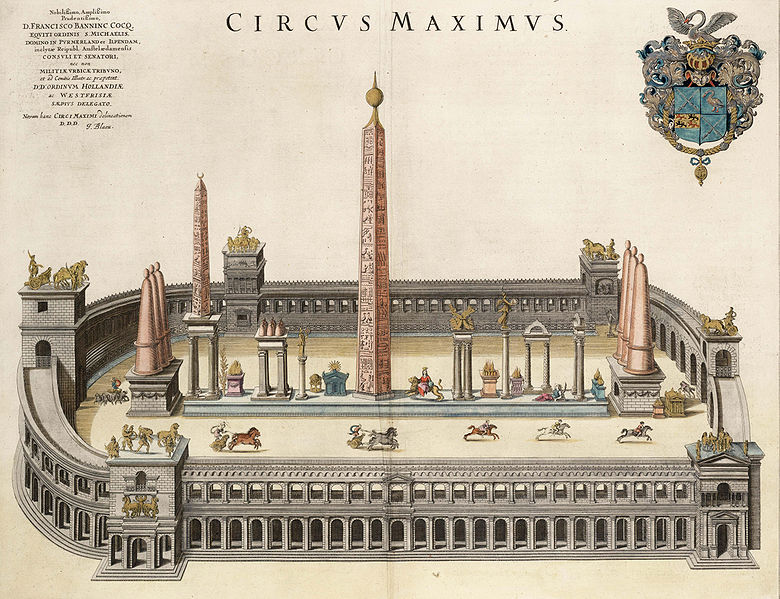

Perhaps the poet and author, Ovid got inspiration for part of his book The Art of Love from Valeria. Only here, he switched the genders so it is a man flirting with a woman. It was written a little over half a century after Valeria picked-up Sulla at a gladiatorial game. Ovid gives advice to men who are looking to meet women. He suggests going to the horse races, as there really isn’t a better place to meet single ladies in Rome. At the end he laments over the chance many must have had to meet beautiful foreigners when Augustus held a mock naval battle in Rome. He says that this must have been so popular all over the world that many must have come to see it, therefore many had a chance to find love with exciting people from distant lands.

CONTENT WARNING

The passage becomes misogynistic as he is belittles women, calling them “light minds.”

Or at the Races, or the Circus[14] Don’t forget the races, those noble stallions: the Circus holds room for a vast obliging crowd. No need here for fingers to give secret messages, nor a nod of the head to tell you she accepts: You can sit by your lady: nothing’s forbidden, press your thigh to hers, as you can do, all the time: and it’s good the rows force you close, even if you don’t like it, since the girl is touched through the rules of the place. Now find your reason for friendly conversation, and first of all engage in casual talk. Make earnest enquiry whose those horses are: and rush to back her favourite, whatever it is. When the crowded procession of ivory gods goes by, you clap fervently for Lady Venus: if by chance a speck of dust falls in the girl’s lap, as it may, let it be flicked away by your fingers: and if there’s nothing, flick away the nothing: let anything be a reason for you to serve her. If her skirt is trailing too near the ground, lift it, and raise it carefully from the dusty earth: Straightaway, the prize for service, if she allows it, is that your eyes catch a glimpse of her legs. Don’t forget to look at who’s sitting behind you, that he doesn’t press her sweet back with his knee. Small things please light minds: it’s very helpful to puff up her cushion with a dextrous touch. And it’s good to raise a breeze with a light fan, and set a hollow stool beneath her tender feet. And the Circus brings assistance to new love, and the scattered sand of the gladiator’s ring. Venus’ boy often fights in that sand, and who see wounds, themselves receive a wound. While talking, touching hands, checking the programme, and asking, having bet, which one will win, wounded he groans, and feels the winged dart, and himself becomes a part of the show he sees. When, lately, Caesar, in mock naval battle, exhibited the Greek and Persian fleets, surely young men and girls came from either coast, and all the peoples of the world were in the City? Who did not find one he might love in that crowd? Ah, how many were tortured by an alien love!

Ovid, The Art of Love, I;5

Further to the idea of the mentor relationship between Pompey and Sulla. After his death, many wished to bury Sulla without the honours granted to Roman viri (plural of vir). Pompey intervenes however, and ensures that Sulla’s body is treated with respect and given an honour burial with all the respective rights for a vir (78 BCE).

Many now joined themselves eagerly to Lepidus, purposing to deprive Sulla’s body of the usual burial honours; but Pompey, although offended at Sulla (for he alone, of all his friends, was not mentioned in his will), diverted some from their purpose by his kindly influence and entreaties, and others by his threats, and then conveyed the body to Rome, and secured for it an honourable as well as a safe interment. And it is said that the women contributed such a vast quantity of spices for it, that, apart from what was carried on two hundred and ten litters, a large image of Sulla himself, and another image of a lictor, was moulded out of costly frankincense and cinnamon. The day was cloudy in the morning, and the expectation was that it would rain, but at last, at the ninth hour, the corpse was placed upon the funeral pyre. Then a strong wind smote the pyre, and roused a mighty flame, and there was just time to collect the bones for burial, while the pyre was smouldering and the fire was going out, when a heavy rain began to fall, which continued till night. Therefore his good fortune would seem to have lasted to the very end, and taken part in his funeral rites. At any rate, his monument stands in the Campus Martius, and the inscription on it, they say, is one which he wrote for it himself, and the substance of it is, that no friend ever surpassed him in kindness, and no enemy in mischief.

Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 38:1-4

MORE ON POMPEY

The following passage furthers the notion that an exceptionally virilis vir (manly man) may be tolerated more in regards affectionate displays because of his proven masculinity. Here is a very exciting passage where Pompey defends himself against three oncoming armies at once, all enclosing upon him from different directions (82 BCE).

There came up against [Pompey], accordingly, three hostile generals at once, Carinas, Cloelius, and Brutus not all in front of him, nor from any one direction, but encompassing him round with three armies, in order to annihilate him. Pompey, however, was not alarmed, but collected all his forces into one body and hastened to attack one of the hostile armies, that of Brutus, putting his cavalry, among whom he himself rode, in the vanguard. And when from the enemy’s side also the Celtic horsemen rode out against him, he promptly closed with the foremost and sturdiest of them, smote him with his spear, and brought him down. Then the rest turned and fled and threw their infantry also into confusion, so that there was a general rout. After this the opposing generals fell out with one another and retired, as each best could, and the cities came over to Pompey’s side, arguing that fear had scattered his enemies. Next, Scipio the consul came up against him, but before the lines of battle were within reach of each other’s javelins, Scipio’s soldiers saluted Pompey’s and came over to their side, and Scipio took to flight. Finally, when Carbo himself sent many troops of cavalry against him by the river Arsis, he met their onset vigorously, routed them, and in his pursuit forced them all upon difficult ground impracticable for horse; there, seeing no hope of escape, they surrendered themselves to him, with their armour and horses.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 7-8;1-3

This was thought to be such a hopeless battle for Pompey that Sulla himself tried to bring his own army to assist him. Imagine Sulla’s surprise upon seeing Pompey was victorious. Sulla treats Pompey with the same respect that is expected to be directed to Sulla himself as Imperator and continues to hold Pompey in highest esteem. Now imagine what the rest of Rome would think about Pompey’s great achievements. This would have enabled him to get away with certain things most would not; things such as tenderness and affection (82 BCE).

Sulla had not yet learned of these results, but at the first tidings and reports about Pompey had feared for his safety, thus engaged with so many and such able generals of the enemy, and was hastening to his assistance. But when Pompey learned that he was near, he ordered his officers to have the forces fully armed and in complete array, that they might present a very fine and brilliant appearance to the imperator[15]; for he expected great honours from him, and he received even greater. For when Sulla saw him advancing with an admirable army of young and vigorous soldiers elated and in high spirits because of their successes, he alighted from off his horse, and after being saluted, as was his due, with the title of Imperator, he saluted Pompey in return as Imperator. And yet no one could have expected that a young man, and one who was not yet a senator, would receive from Sulla this title, to win which Sulla was at war with such men as Scipio and Marius. And the rest of his behaviour to Pompey was consonant with his first tokens of friendliness; he would rise to his feet when Pompey approached, and uncover his head before him, things which he was rarely seen to do for any one else, although there were many about him who were of high rank.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 8

Pompey is quite an emotional man; I imagine his reputation would be quite low if he wasn’t such an accomplished general: In the following passage, Pompey is ordered to send his army home, but to remain where he is with a small force until the next general arrives. His soldiers are infuriated by these orders and Pompey is unable to calm them down. He becomes so overwhelmed by emotion because of this that he starts weeping and eventually threatens to kill himself if they don’t listen. This is an example of a successful vir acting basically the opposite of how a successful vir should act (81 BCE).

On his return to Utica, a letter from Sulla was brought to him, in which he was commanded to send home the rest of his army, but to remain there himself with one legion, awaiting the arrival of the general who was to succeed him. Pompey himself gave no sign of the deep distress which these orders caused him, but his soldiers made their indignation manifest. When Pompey asked them to go home before him, they began to revile Sulla, declared they would not forsake their general, and insisted that he should not trust the tyrant. At first, then, Pompey tried what words could do to appease and mollify them; but when he was unable to persuade them, he came down from his tribunal and withdrew to his tent in tears. Then his soldiers seized him and set him again upon his tribunal, and a great part of the day was consumed in this way, they urging him to remain and keep his command, and he begging them to obey and not to raise a sedition. At last, when their clamours and entreaties increased, he swore with an oath that he would kill himself if they used force with him, and even then they would hardly stop.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 13

Pompey seems to have been humble and gentle for the most part; Pompey is reluctant to receive the name “The Great.” (80 BCE)

But when [Sulla] learned the truth, and perceived that everybody was sallying forth to welcome Pompey and accompany him home with marks of goodwill, he was eager to outdo them. So he went out and met him, and after giving him the warmest welcome, saluted him in a loud voice as “Magnus,” or The Great, and ordered those who were by to give him this surname. Others, however, say that this title was first given him in Africa by the whole army, but received authority and weight when thus confirmed by Sulla. Pompey himself, however, was last of all to use it, and it was only after a long time, when he was sent as pro-consul to Spain against Sertorius, that he began to subscribe himself in his letters and ordinances “Pompeius Magnus”; for the name had become familiar and was no longer invidious.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 13:4-5

Pompey was not someone to adhere to social traditions. He was a very bold man who was definitely willing to push the boundaries, especially in times of general instability in regards to the social order and political system. He is more interested in pursuing exactly what he wants, rather than conforming to the conventional social order (80 BCE).

Pompey, however, was not cowed, but bade Sulla reflect that more worshipped the rising than the setting sun, intimating that his own power was on the increase, while that of Sulla was on the wane and fading away. Sulla did not hear the words distinctly, but seeing, from their looks and gestures, that those who did hear them were amazed, he asked what it was that had been said. When he learned what it was, he was astounded at the boldness of Pompey, and cried out twice in succession: “Let him triumph!” Further, when many showed displeasure and indignation at his project, Pompey, we are told, was all the more desirous of annoying them, and tried to ride into the city on a chariot drawn by four elephants; for he had brought many from Africa which he had captured from its kings. But the gate of the city was too narrow, and he therefore gave up the attempt and changed over to his horses. Moreover, when his soldiers, who had not got as much as they expected, were inclined to raise a tumult and impede the triumph, he said he did not care at all, but would rather give up his triumph than truckle to them. Then Servilius, a man of distinction, and one who had been most opposed to Pompey’s triumph, said he now saw that Pompey was really great, and worthy of the honour. And it is clear that he might also have been easily made a senator at that time, had he wished it; but he was not eager for this, as they say, since he was in the chase for reputation of a surprising sort. And indeed it would have been nothing wonderful for Pompey to be a senator before he was of age for it; but it was a dazzling honour for him to celebrate a triumph before he was a senator. And this contributed not a little to win him the favour of the multitude; for the people were delighted to have him still classed among the equestrians[16] after a triumph.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 14:3-6

Here we can observe elements of Pompey’s loyalty. As the passage above said that Pompey was always faithful to his wife, we can infer that loyalty was a large part of his charter as he is incredibly loyal to Sulla, even after he was slighted in his will (78 BCE).

Sulla showed most clearly that he was not well-disposed to Pompey by the will which he wrote. For whereas he bequeathed gifts to other friends, and made some of them guardians of his son, he omitted all mention of Pompey. And yet Pompey bore this with great composure, and loyally, insomuch that when Lepidus and various others tried to prevent the body of Sulla from being buried in the Campus Martius, or even from receiving public burial honours, he came to the rescue, and gave to the interment alike and security.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 15:2-3

Pompey’s brashness transcends the natural order of societal propriety. Pompey doesn’t subjugate himself to those who should technically have power over him and people love him for it. This is a great example of certain actions being excusable or even overlooked due to the virtus of the person.

It is customary for a Roman knight, when he has served for the time fixed by law, to lead his horse into the forum before the two men who are called censors, and after enumerating all the generals and imperators under whom he has served, and rendering an account of his service in the field, to receive his discharge. Honours and penalties are also awarded, according to the career of each.

At this time, then, the censors Gellius and Lentulus were sitting in state, and the knights were passing in review before them, when Pompey was seen coming down the descent into the forum, but leading his horse with his own hand. When he was near and could be plainly seen, he ordered his lictors to make way for him, and led his horse up to the tribunal. 6 The people were astonished and kept perfect silence, and the magistrates were awed and delighted at the sight. Then the senior censor put the question: “Pompeius Magnus, I ask thee whether thou hast performed all the military services required by law?” Then Pompey said with a loud voice: “I have performed them all, and all under myself as imperator.” On hearing this, the people gave a loud shout, and it was no longer possible to check their cries of joy, but the censors rose up and accompanied Pompey to his home, thus gratifying the citizens, who followed with applause.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 22:4-6

Plutarch on Cato the Elder’s regard for public displays of affection: This is what the Roman’s ideal Roman would think about affection (around 170 BCE.)

Cato expelled another senator who was thought to have good prospects for the consulship, namely, Manilius, because he embraced his wife in open day before the eyes of his daughter. For his own part, he said, he never embraced his wife unless it thundered loudly; and it was a pleasantry of his to remark that he was a happy man when it thundered.

Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder, 17:7

Plutarch comments on the same occasion in his Moralia. This demonstrates how it was very much against convention for Pompey to display such emotion and affection on several different occasions and for Sulla to openly flirt with a women at a public spectacle.

Cato expelled from the Senate a man who kissed his own wife in the presence of his daughter. This perhaps was a little severe. But if it is a disgrace (as it is) for man and wife to caress and kiss and embrace in the presence of others, is it not more of a disgrace to air their recriminations and disagreements before others, and, granting that his intimacies and pleasures with his wife should be carried on in secret, to indulge in admonition, fault-finding, and plain speaking in the open and without reserve?

Plutarch, Moralia, 139 E 13: 1-3.

Key Question

Why do you think that these men were able to express affection towards their loved ones despite the fact that it was looked down upon by the upper-class Roman society?

- To what extent does virtus affect their decisions and the public’s reception of them?

- How exceptional do you think these men truly were in their affection? Are these really the only men from the late republic to act in such a way, or could it be possible that there were others who were not recorded or weren’t noteworthy enough to inscribe in the Roman’s histories?

CATULLUS

The following contains some of the poetry of Catullus. Although he came from a wealthy family, he lived no traditional upper-class life, and basically devoted his work to subverting the notion of “Vir.” His poetry was received with mixed reviews among his contemporaries. The Late Republic was a very tumultuous time for one to live, and as history has shown time and time again, art criticizing the system flourishes in times of unrest. Catullus criticized Julius Caesar and Sulla themselves in his poetry, made proclamations of his love and lust, and introduced an entire new style of verse that shattered the preexisting notion of what poetry should be.

Daisy Dunn writes:

He feverishly combined elegantly phrased sentiment with colloquialisms and obscenity, unnerving the more serious Romans who believed that a jibe at one man’s sexual inadequacy was what high-spirited youths scribbled on walls and brandished in tense moments, not what educated writers preserved in fine papyrus scrolls. His work would therefore prove unsettling for some of the older generation, as well as important public figures such as Cicero… who had rather conservative tastes.

Daisy Dunn, Catullus Bedspread, The Life of Rome’s Most Erotic Poet (pg. 6)

The first poem we will explore is one of Catullus’ most famous. It is directed towards his lover, Lesbia[17] (this is the literary pseudonym given to whom scholars speculate to be Clodia)[18] (95-44?BCE). He encourages her to ignore the slander and prying eyes of others and to instead relish each other and to allow their passion to enrich their lives, rather than concerning themselves with the angry opinions of “evil peasants.”

Lesbia, come, let us live and love, and be

deaf to the vile jabber of the ugly old fools,

the sun may come up each day but when our

star is out…our night, it shall last forever and

give me a thousand kisses and a hundred more

a thousand more again, and another hundred,

another thousand, and again a hundred more,

as we kiss these passionate thousands let

us lose track; in our oblivion, we will avoid

the watchful eyes of stupid, evil peasants

hungry to figure out

how many kisses we have kissed.

Catullus, Poem 5

Here Catullus mocks his friend Calvus[19] (82- 47 BCE), saying he was ruined by the bad poetry his friend sent to him, saying the only way it makes sense for Calvus to have sent the poetry was that the Dictator Sulla commanded it.

Calvus, if I did not love you as my own

two eyes, I’d hate you as we hate Vatinius.

Do you not recall

the present you sent me? What is it I did–

what did I say, what wrong did I do–

that you so wish to destroy me?

May the gods bring punishment on your client

who sent you that collection of poetic inanity.

If this fine, new book

arrived by way of Sulla, as I would suspect,

it would not be upsetting, no.

I’d be pleased: for it would mean

you were paid for your work.

What a foul thing you’ve done.

Was your intention, then, to unhinge your Catullus

at the very start of Saturnalia, best of days? No matter.

Come morning, I’ll raid the shelves

of the booksellers. I’ll gather

the worst of Caesii, Aquini, Suffenus–

all that’s utterly stupid and worthless

and I’ll get payback.

In the meanwhile, poets, be gone,

get as far away from me as possible.

On gangrenous feet return to the place

you came from. You are blemishes

on our age, you most stupid of poets

Catullus, Poem 14

Some of the poetry that upset the upper-class:

CONTENT WARNING

The following poem engages in threats of sexual assault.

Aurelius and Furius: little cocksuckers

I’ll fuck you up the ass

and stuff your mouths!

You who think

since my poems are delicate I’m less than chaste.

It’s well known that a poet who is devoted need not

be upstanding in his verses.

It’s clear that my lines are charming, witty.

Then what of it if they’re a tad soft

a bit shameless at times

so long as my readers get turned on?

Mind you I’m not talking about healthy boys, but hairy

old geezers who can’t get it up

by standard methods.

Yet you still think because

I’ve spoken of a good many kisses

I’m somehow less than a man?

Yeah, I’ll fuck you up the ass

and stuff it in your mouths.

Catullus, Poem 16

The following is a love poem. Catullus describes how his love for Lesbia has turned into more of a twisted obsession in which he reviles and reveres her simultaneously. He cannot be happy for her even if she becomes incredibly successful, nor can he stop loving her even if she commits a terrible deed.

At this point [my] mind is so broken down by your doing

my Lesbia,

that it destroys itself by its own devotion

so that it can no longer wish you well

even if you should become the best

nor can it stop loving you

no matter what you should do.

Catullus, Poem 75

Further the point of Catullus being overwhelmed by his passion for Lesbia; so much so that his emotions conflict like two colliding waves crashing into each other. Here is Odi et Amo, I hate and I love[22].

I hate and I love.

Why I do this, perhaps you ask

I know not,

But I feel it happening

And I am tortured.

Odi et Amo

LOVING HUSBANDS, LOVING FATHERS

The following funerary inscription is significant because, although many scholars argue that “well-deserving spouse” was a stock phrase used on funerary inscriptions throughout the Roman world, the name of the child these two had together is larger than the Man’s name and his occupation on the tombstone. This is should not be overlooked, as it implies that this child was the most important thing in his life, as well as his wife’s. The fact that their child died at the age of two is deeply tragic. This inscription goes to show that, despite the fact that infant mortality was high in the ancient world, the people who experienced it were not numb to it in the slightest. Rather, they were loving parents who were devastated by the death of their child.

I have roughly translated an inscription below:

To the spirits of the dead, Quintus Julius Martialis, served as a soldier for 21 years, and lived to 46. He was a patron and well-deserving spouse to Julia Sopatra. And Fortunata, his daughter lived to 2.

Robert Knapp quotes two examples in Invisible Romans of funerary inscriptions showcasing a tender love of husbands for their deceased wives. [20]It is quite beautiful as it expresses how important these people where to their loved ones, and how the ancient Romans experienced love just as we do, perhaps with the exception of the sexist Roman value of women not quarrelling with the men… However, don’t we all hope to meet someone who can be “my everlasting solace[?]”

This is the gravestone Gaius Aonius Vitalis set up for Atilia Maximina, she of purest spirit, an incomparable wife, who lived with me without any quarrels for 18 years, 2 months, and 9 days, having lived 46 years, leading a life of honor and good name, my everlasting solace. Farewell. (CIL 5.3496)

Pompullius Antiochus, her husband, set up this gravestone to Caecilia Festiva, his dearest, sweet wife, hard-working and well-deserving, who lived with me 21 years without a contrary word. (CIL 9.3215)

Plutarch wrote about Cato the Elder, praising him for being a loving father and a loving spouse. Within this praise, Plutarch also finds time to celebrate Cato’s wife for not using a wetnurse. The fact that Plutarch points these instances out indicates that neither Cato’s kindness towards his family nor his wife feeding their child were normative behaviour at the time.

Therefore I think I ought to give suitable examples of [Cato’s] conduct in these relations. He married a wife who was of better family than she was rich, thinking that, although the rich and high-born may be alike given to pride, still, women of great families have such a horror of what is disgraceful that they are more obedient to their husbands in all that is honourable. 2 He used to say that the man who struck his wife or child, laid violent hands on the holiest of holy things. Also that he thought it more praiseworthy to be a good husband than a good senator, and that there was nothing else to admire in Socrates of old except that he was always kind and gentle in his intercourse with a shrewish wife and stupid sons. After the birth of his son, no business could be so urgent, unless it was public affairs, that it prevented him from being present when his wife bathed and swaddled the babe. 3 For the mother nursed it herself, and often breast fed also to the infants of her slaves, that so they might come to cherish a brotherly affection for her son.

Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder

Sources and Further Reading:

Bibliographic Recommendation: Catullus’ bedspread by Daisy Dunn. Dr. Dunn is a gifted writer and effortlessly bridges the gap that exists in translated poetry. She provides fantastic translations of Catullus works, as well as occasionally explaining why the original latin is so effective. She takes you through Catullus’ short life and provide insight into his mind and heart. It is a refreshing change of pace to read something by a scholar that doesn’t feel like it was written by one! It flows nicely and is actually informative as well as being a page-turner (a rare thing for the scholarly literature of the classicists). We definitely recommend checking this out if you found Catullus’ section interesting.

Clst 260 Spectacle Reader

Livius: https://www.livius.org/category/roman-republic/

Plutarch’s Histories: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Pompey*.html#9.2

Plutarch, Life of Sulla

Plutarch, Life of Pompey

Ovid, Ars Amatoria: http://www.yorku.ca/pswarney/Texts/aa-kline.htm#_Toc521049265

Dunn, D. (2016). Catullus’ bedspread: the Life of Rome’s Most Erotic Poet . New York: HarperCollins.

Knapp, Robert (2011), Invisible Romans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbpmg .

Catullus Poetry: I mainly used wiki commons as I think the translation was the best, but I also used the following:

http://intranslation.brooklynrail.org/latin/eleven-poems-of-catullus

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/gaius-valerius-catullus

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Catullus_75

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0003%3Apoem%3D85

Media Attributions

- 411px-Pompey_the_Great

- Sulla_Glyptothek_Munich_309

- Viri is the plural of Vir, Latin for “man.” But it means something more like manly man. ↵

- Piso was consul in the year 58 BCE. He was Julius Caesar’s father-in-law and a political adversary of Cicero. Piso tried to act as mediator between Julius and Pompey in their civil war, but left the city in protest when Julius marched on Rome. He did however insist on a public funeral for the dictator after Julius Caesar was assassinated. He also tried to act as a neutral party between Octavian and Mark Anthony during their civil war. He was an epicurean and actively worked for peace during both civil wars. ↵

- The Campus Martius (Latin for the "Field of Mars", Italian Campo Marzio) was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome extending about 2 square kilometres ( ↵

- Antistia was the daughter of Publius Antistius. She was the first wife of Pompey from 87-82 BCE. This occurred after he was indicted on charges of embezzelment of plunder. Antistia's father was the judge of Pompey's trial. He made a deal with Pompey wherein Pompey would marry Antistia in exchange for being acquitted. ↵

- Sulla’s step-daughter. Aemilia was daughter of Caecilia Metella Dalmatica. She would be married to Pompey until she died during childbirth. ↵

- This Catulus—not be confused with our friend, Catullus the poet— was named Quintus Lutatius Catulus (120–61/60 BCE). He was sometimes called "Capitolinus" for his defence of the capital in 77 BCE. He was a politician, not a poet. ↵

- Metella was the fourth wife of Sulla, and he seemed to have loved her quite a bit as Plutarch wrote that it was thought that when Sulla took Athens, he punished the people severely because they had written slander about Metella on their walls. Their marriage was looked down upon by the upper-class as many didn’t respect Sulla and considered the marriage ‘beneath her.’ ↵

- [10] Sulla was an augur, a type of Roman priest that observed and interpreted messages from the gods. We know this in part from his coinage which feature the instruments of the augur like the lituus, the curved wand (see Fig.1). Death was considered to be polluting, so individuals with a religious function like augurs or other priests had to avoid contact with dead bodies, funerals, etc. So Sulla divorced his wife at the request of the other augurs to avoid being connected to her and thus polluted by her when she dies. ↵

- This is translated in the text as ’superstition’ but that’s a poor translation of the word ’superstitio’ in Latin which means something more like religious obligation/observance. Non-priests certainly would not have to divorce a sick wife—in fact there are laws against abandoning a sick slave, so presumably abandoning a sick wife would have been even worse. ↵

- There are no accurate dates for Valeria. Historians estimate she was born between 168-108 BCE, as there are no real accurate descriptions given about Valeria (thanks a lot patriarchy) ↵

- this is my favourite passage in the reader because it’s so adorable ↵

- This basically means that Sulla thought she was beautiful and that’s why he married her. ↵

- This Translation comes from a webpage that reproduces The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IV of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1916. What I find interesting about this is that this translation is over a century old, and gives us some insight into the way the english language worked at the time. ↵

- Here Ovid is referring to the Circus Maximus, the largest horse-track in Rome, it may have been built as early as the 6th Century BCE. It could hold around 150,000 spectators. ↵

- Latin for Commander or General ↵

- The Equestrian was an upper-class of Romans but it was still technically below the senatorial class. ↵

- His nickname for Clodia: Lesbia, is a reference to the island of Lesbos, on which the famous poet Sappho lived! Kutzko, David. 2006. "Lesbia in Catullus 35." Classical Philology 101 (4): 405-410. ↵

- Clodia was the daughter of a famous Roman Patrician and was in an unhappy marriage with Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer. She was famous for her ability to drink and her proclivity for gambling. She is speculated to have had many affairs with different men, including Catullus. ↵

- Calvus was an orator and poet of ancient Rome. Son of Licinius Macer, he was Catullus’ Friend, and they shared a similar style and subject matter of poetry. ↵

- KNAPP, ROBERT. Invisible Romans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbpmg . ↵