10.2: Hybrid States in Northern China and the Steppe

- Page ID

- 135144

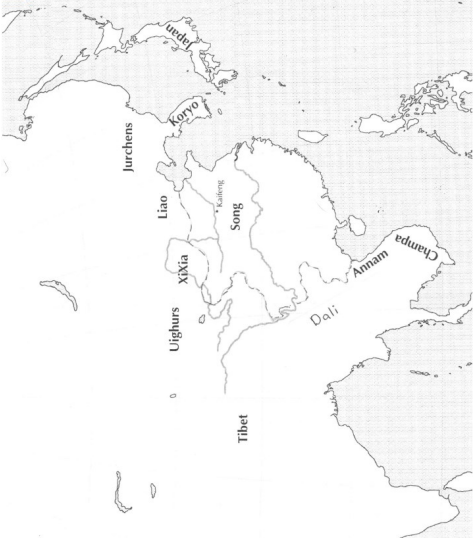

The collapse of the Tang state in 907 set the stage for an entirely new situation in East Asia. The eastern half of Tang territory was reunited, after five decades, by the Song, which drew on the long heritage of the bureaucratic state, taxing farmers as part of its fiscal base. But along the northern border, several new states arose, which historian F. W. Mote calls “hybrid states.” Even more dramatically than Tang and Sui, they combined mainland traditions of rule with nomadic traditions of rule, and made competing claims to the Mandate of Heaven. Three hybrid states coexisted and fought with Song: the Liao state founded by the Khitan tribes (907- 1125), the Xi Xia state founded by the Tanguts (1038-1237), and the Jin state founded by the Jurchens (1115-1234), which conquered North China in 1127. The Song court fled from Kaifeng to Hangzhou and regrouped as what is known as the Southern Song (1127-1279). In the end, a fourth hybrid state, the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1234-1367) defeated Xi Xia, Jin, and Song and reached into Koryŏ.

Liao

The Liao emerged even before the collapse of Tang. Its founder, Abaoji, became khan in 901, but with the fall of Tang in 907, he faced the challenge of holding together a nomad confederation when there was no centralized government to his south to extract goods from. Although Modun, in Han times, had overseen some farmers, he had not been able to stop the Xiongnu chiefs below him from raiding across the border, nor transform the confederation into a more centralized form of government. Abaoji did. Treating settled farmers as a conquered tribe, he nevertheless managed them with a bureaucratic administration called the Southern Chancellery, while continuing to manage nomads as a tribal confederation under the Northern Chancellery. This innovation – a hybrid administration for settled and nomadic subjects – enabled Abaoji to overcome rebellions and to establish a somewhat more stable line of succession than was usual in steppe empires. Of course, this double administration was pricy: the chiefs wanted a steady supply of goods, and officials needed salaries.

How could Abaoji keep the tribesmen from raiding? He did so by choosing a particular area of settled territory in northern China, just on the other side of a line of fortified passes – about where the later Great Wall would be. As dozens of warlords cycled through the thrones of former northern Tang territory, Abaoji’s son and successor incorporated the target territory into the Southern Chancellery. This area, called “the Sixteen Prefectures,” was recognized by Northern Song (960-1127) as being part of Liao, in the Treaty of Chanyuan in 1005. The first clear border in East Asian history, the Song/Liao border ran to the south of the Sixteen Prefectures. It was marked most dramatically with man-made lakes and ponds (dubbed by one historian “the Great Ditch”) and a new forest of fast-growing elm and willow trees (the “Green Great Wall”): a barrier to defend the Song capital of Kaifeng.16 Liao and Song both observed the border. Peace held for decades, with diplomatic missions going back and forth, sharing travel, banquets and poetic toasts.

In the end, however, tempted by the weakening of Liao, Song hawks finally pressed their claim that without this area, the Song Mandate of Heaven was incomplete.17 In 1122, Song broke the Chanyuan peace. To attack Liao, Song troops cut down the forest. A few years later, Jin cavalry easily crossed the once more “barren, tree-less moonscape” southward to conquer Kaifeng and end the Northern Song.18

Xi Xia

The Xi Xia state of the Tanguts adapted Abaoji’s dual structure. The Tanguts lived where steppe met sown in the far northwest. They had been subjects of the Tibetan empire at its height and were then caught between Song and Liao. In self-defense, they created a nomadicstyle military force, even though many of them had long been farmers. They did so by adding to their expertise and investment ranching and state-sponsored horse-breeding to support cavalry, and incorporating smaller tribes along the steppe margin. As they built up their forces, they paid tribute to both Song and Liao.

All these efforts came to fruition in 1032 when a man named Yuanhao became ruler of the Tanguts. Yuanhao had distinguished himself in the new nomadic lifestyle by leading campaigns out along the oases of the Silk Road, an area that could provide rich pasture for raising horses. Yuanhao moved closer to a tribal model, training all young men to fight, and drawing elite sons into his kesig honor guard. But at the same time he sponsored a new script to keep records in Tangut. The script was loosely based on Chinese characters. In 1038, Yuanhao finally declared the Xi Xia a new dynasty, and himself the emperor, with his own Mandate.

The hybrid Xi Xia state was strong enough to play off both Liao and Song. On the one hand, Liao protected Xi Xia as a counter-balance to Song; on the other, Song decided that its vast wealth was better deployed by paying the other two off than by trying in vain to defeat their impressive cavalries. And as the Rong and the Di had done in Zhou times, the Xi Xia and Liao buffered Song from more powerful military forces – for a while.

Jin

The Jurchens, who founded Jin, created a third variation on the hybrid state. The Jurchens began as dispersed forest tribes in Manchuria. Some, called in the records “tame” Jurchens, were incorporated into the Liao tribal confederation; the so-called “wild” Jurchens were huntergatherers living in scattered villages and doing a little farming and pig-raising. They first learned to work iron only about 1074, and about the same time, the Liao designated one of their chiefs “military governor” of all the wild tribes, providing a basis for organization. Over the next two generations, the emerging Jurchen confederation learned equestrian skills and became great cavalrymen.

Resenting Liao oppression, the Jurchen leadership quickly developed a centralized, army based on a decimal units – easier for them since the tribes were small and weak to begin with. In 1114-15 a leader named Aguda attacked the Liao border, took a key strategic spot, declared the establishment of the Jin state, and with the support of other rebel tribes and mutinous Khitan forces completely took over the Liao’s Northern Chancellory in 1122, recreating a tribal confederation. In the Southern Chancellery, the Jin quickly gained the services of both Khitan and Song defectors with experience. These recent “wild tribes” quickly came to control a hybrid agricultural-nomadic state.

According to a secret alliance made between Jin and Song in 1115, Song was supposed to capture the Liao southern capital within the Sixteen Prefectures, while the Jin conquered the Northern Chancellory, but the Song campaign had failed utterly. Liao took the area, looted it, and then turned it over to Song. Negotiations resumed, but when Aguda died, his brother let his generals do as they liked, and they quickly retook the Sixteen Prefectures, and then went further south. The result was that in 1127 the Song emperor surrendered the capital, Kaifeng, to Jin, and the imperial family were marched off to the northwards, in humiliation and misery, through what was now all Jin territory. Eager to consolidate a sole claim to the Mandate of Heaven, Jin forced Xi Xia to acknowledge their superiority in exchange for continued independence, and pursued the one Song prince who escaped Kaifeng far into central China. He escaped only by boarding a ship and sailing down the coast, and eventually established a new capital at Hangzhou, founding the Southern Song.

The Jin regime quickly decided that Song constituted no real threat. The real threat lay in the newly-rising Mongol confederation. More useful than a claim to the mandate was tribute that could be passed along to hold together the tribal side of the hybrid state. And the immense riches of the Song state were the obvious source of such tribute.