8.4: The Tang Civil Service Examinations

- Page ID

- 135136

The civil service examinations never selected enough officials from non-aristocratic families to undermine the great clans. Instead, as the exams became the more prestigious route to office, the great clans maintained their power through the examinations, in Penelope Herbert’s phrase “by fair means or foul.” Foul means of dominating the exam system included bribing corrupt and incompetent exam officials, or corrupt local headmen who had to certify who was eligible for exam, as well as good connections that enabled top families to send sons to state colleges that funneled men into the bureaucracy. Fair: even after printing was invented under Empress Wu, books were relatively scarce. Owning books, or having access to the libraries of other noble families was a privilege of the few. Most pupils got their basic schooling at home from their fathers, or more often (since they were often away in office or at court) their mothers. Those who did not have books could study at Buddhist monasteries, whose libraries held not just scriptures but the Classics and literature as well. But one still needed the leisure to learn without having to earn a living.

Furthermore, one had to be recommended to take the examinations, and they were not anonymous. Examiners knew the candidates, and were supposed to judge them in part on their personal (and hence also familial) characteristics. To do well, it was essential to submit writing samples ahead of time to the chief examiner, and impression on him and other influential people with one’s poetic and musical talents, and one’s sociability, appearance, and knowledge of etiquette, so complex that it was hard to learn if one had not grown up in an elite family. (Many Tang tales, like the story of Li Wa the loyal courtesan, were written by scholars for pre-exam presentation.) Commoners and members of the scholar clans could not do as well as those who had grown up in the highest social circles. If a social nobody did indeed have great literary talent, he often had a dream in which his heart and guts were cut out: this miraculous bodily transformation explained his extraordinary success. (High-ranking aristocrats, by contrast, dreamt of ghosts when they were going to fail.)13

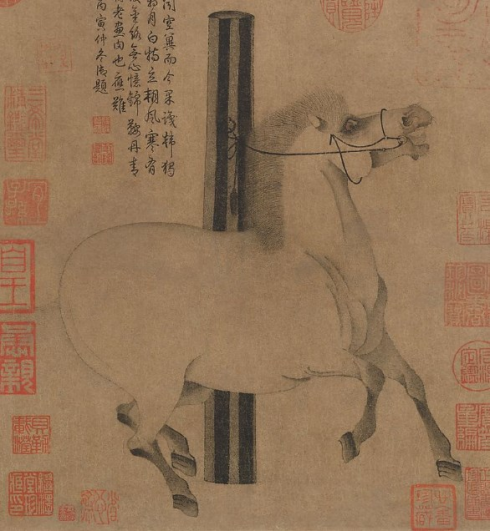

Family and social connections constituted the real strength of the aristocracy: patrilineal kin, matrilineal kin, marital connections, and native-place connections all helped assure careers and get the work of government done. But increasingly, perhaps because of the mainland heritage of meritocracy, Tang men disdained to hold office purely by right or through connections. The most prestigious route to office was through the written examinations, which tested poetry-writing and calligraphy and secondarily required essays on philosophical and political issues. Careers depended on talent in poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music, and families boasted not merely of their illustrious ancestors but also of their abilities and their virtues. Meritocracy was meant to select the wisest and most virtuous to govern; and in Tang thinking, virtue lay in family and in learning.

Tang Confucianism

Tang Taizong advised his heir: “The Way (dao 道) is spread through culture (wen 文); fame is gained through learning.” This was an aristocratic credo, for “culture” included all the practices of the great clans. “This culture of ours” they called it, thinking of Analects 9.5. An eightfold chain of historical reasoning linked cosmic patterns (the Way) to elite culture.

- Humans in nature. Humans began as part of Heaven and Earth and the myriad living beings of the world.

- Sage-kings create civilization. Then the sage-kings of Xia, Shang, and Zhou brought humanity out of the realm of nature by creating civilization. The sage rulers included Yao, Shun, and Yu; Tang the founder of Shang; King Wen, the Zhou progenitor, and the Duke of Zhou. Observing the patterns of nature (seasons, star movement, life cycles), they translated them into stable guides for humanity: calendars, hierarchies, boundaries. Since all elements of the cosmos resonated with one another, ordering human life properly could bring order to the cosmos.

- Civilization in Zhou. The writing, rituals, calendars, institutions, implements, and arts created by the former kings continued be elaborated, creating the Six Arts of the Zhou.

- The Five Classics. The Six Arts, and the world of the sage-king and their ministers were recorded in the Five Classics. Tang people believed that through the Classics we can still know what happened in Xia, Shang, and Zhou. They did not worry about the histories of compilations, or whether some had been forged. They accepted the Classics at face value.

- Confucius. Confucius played a key role, for they thought he had written or edited the Classics. Confucius, they thought, had chosen the 305 poems of the Book of Poetry from more than 3000 in oral tradition. He had compiled the Book of Documents. He wrote a commentary on the Book of Changes, and composed the Spring and Autumn Annals. His disciple Zengzi and his grandson Zisi contributed to the three rites classics. Confucius, the first teacher and a sage himself, had put the Classics in order, to record and clarify and preserve the model world of the sage rulers as his world declined. He preserved antiquity.

- Decline. In the Late Zhou, people had turned away from the institutions and practices of the golden age of antiquity.

- The Break. The Qin purposely broke with antiquity by destroying feudalism.

- Restoring antiquity. But the Han and the Tang, by looking back to the Classics, as interpreted by Confucians, had “restored antiquity.” They had restored its spirit and its outlines. They did not follow the exact same institutions as the sage-king Yao, because they saw institutions as having developed historically in civilization before the decline, but their institutions were based on the Classics, and hence ultimately on cosmic patterns.14

In the view of the Tang elite, their government, writing, ritual, arts, and personal behavior; their friendships, in which they mutually cultivated virtue and deeply understood each other; and even their leisure pastimes came in an unbroken line of transmission from those of ancient times, which in turn had been patterned on the intrinsic nature of the cosmos. All the practices of the great clans expressed cosmic patterns. Doing culture was aligning humanity with the cosmos. Culture was the Way. Culture was what gave a person merit; and what meritorious persons – those with long, illustrious traditions of family education and achievement – did, was culture.15