8.1: Ethnicity

- Page ID

- 135133

Sui founding emperor Yang Jian (541-604), who ruled as Wendi, and his empress both illustrate the difficulty of categorizing anyone as “Chinese” or “non-Chinese” in the medieval period. Yang Jian was born in the heartland between the old capitals of Chang’an and Loyang, but his ancestors for six generations back had worked on the northwestern frontier and intermarried with Turko-Mongol (Xianbei) families there. His father worked for the Northern Wei until it split in half, and then for a Xianbei ruler. Until he was ten years old, Yang Jian was raised by a Buddhist nun; he then learned hunting and riding, and attended a Confucian school in the capital. At age thirteen he was appointed to office and rose quickly, perhaps because of his powerful father. At age sixteen he married a thirteen-year-old girl descended from a very highranking northern Chinese family on one side and from several Turko-Mongol families that served the Northern Wei on the other side. She was highly educated, good at practical management, and a devout Buddhist. The young couple vowed to marry no-one else, and eventually had at least ten children.1 Their mixed cultural heritage was typical of the ruling class.

The Tang royal family, surnamed Li, also came from Turkic and Central Asian groups. The Tang founder, Gaozu, had made his eldest son heir apparent, but the second son, claiming that there was a plot against his own life, killed his elder brother and forced his father to abdicate in 626. Sanping Chen argues that this was not merely the usual brutal behavior of royalty, but an instance of Turkic practice of “tanistry.” In contrast to the Zhou model of trunk and branch lineages with the eldest son of the primary wife inheriting, a pattern reinforced by Han patrilinealists, tanistry meant that the most qualified son, or the one who could gather the most support among the ruling group, inherited leadership. Underlining Chen’s emphasis on the Turkic roots of the imperial family, one early Tang prince refused to speak Chinese, lived in a tent, and wore Turkish clothes.

Tang incorporated international talent: the son of a Koguryŏ general captured by TangSilla forces served in the Tang army thereafter, and his son Gao Xianzhi carried out Tang foreign policy in Central Asia. Tang general An Lushan was part Turkish and part Sogdian, a Persianspeaking group who lived around Samarkand. An was adopted by the imperial consort Yang Guifei, and Emperor Xuanzong trusted him so deeply that he wished to make him Prime Minister, although he was apparently illiterate. In 755, General An, in charge of a hundred thousand troops fighting the Khitans in Manchuria, rebelled against Tang. Xuanzong and Yang Guifei fled Loyang (his troops murdered her along the way, causing him great grief), and An Lushan was defeated by Uighurs allied with Tang.

If An Lushan had succeeded in replacing Tang, it would have been the third successive dynastic change via coup d’etat by a mixed-ethnicity general overthrowing the mixed-ethnicity emperor for whom he worked. Even below the elite level, medieval Chinese people, from the fall of Han through the Tang, spoke many languages, cooked many cuisines, wore many styles of clothing, and carried out different family rituals. And people of different cultures intermarried and raised children together. Ethnic categories were flexible.

Tang also employed and welcomed foreigners. Foreign merchants of many kinds – Jews, Arabs, Persians, and South Asians –established communities in the capital and Tang ports, and made great profits. After the defeat of Koguryŏ, up to 5% of its population was moved to the mainland, and the descendants of both Koguryŏ and Paekche immigrants entered Tang military service.2 The Yamato court and Silla sent members of the elite to study in Tang. In 837 alone, a state record counted 216 Silla men studying in Tang.3 The special Tang examination for foreigners, which 58 Silla men passed, was a route into office back in Silla for head-rank six men; but others migrated to Tang and stayed there. A tomb inscription of about 693 tells us that the wife’s surname was Xue (= Sŏl, 薛); her head-rank six family had served the Silla dynasty for generations, until her father became a Tang military general. The inscription also claimed that Xue was descended from a very early Korean king.4 Both examination degrees and high social rank were meaningful across international boundaries.

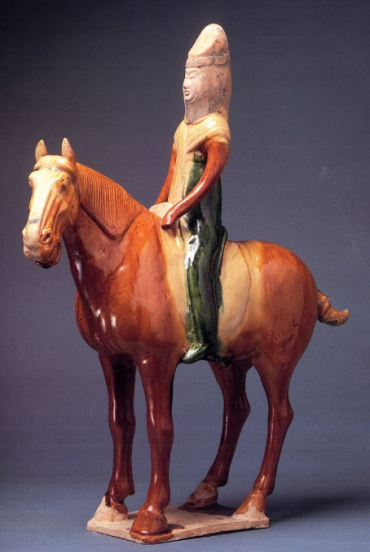

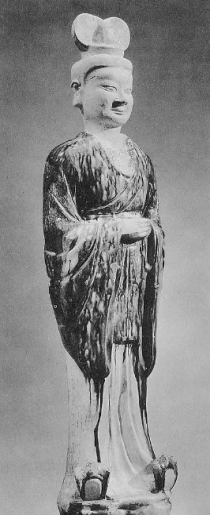

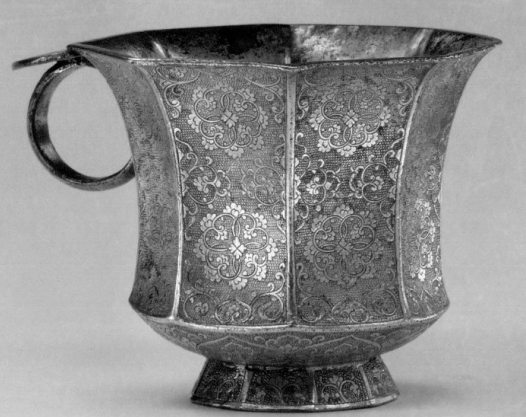

Tang Taizong learned court style from a Sassanid shah in Persia (Iran). The imperial family ate off gold and silver vessels in Persian styles. Horses from Persia were Taizong’s pride, in war and in peace; Tang ceramic sculptures of polo-players, male and female, survive from many tombs. In Xuanzong’s reign, courtiers loved Persian music and dance. The famous poet Li Bai immortalized one dancer as “the whirling girl,” but rebel general An Lushan and Xuanzong’s true love, Yang Guifei, both also excelled in the dance.5 The court purchased or demanded as tribute most imported luxury goods: sandalwood, ivory, frankincense, spices, jewels, and pearls that came in from countries well-represented in Tang geographical works -- Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Iran, and Iraq -- as well as Bahrain, Oman, Yemen, and even Tanzania. Tang merchants sailed to Japan, Korea, and southeast Asia, and reached India and even the Persian gulf by about 850.6 Arab, Persian, and Indian merchants brought imports to Guangzhou (Canton), Quanzhou, and Yangzhou, buying silk, porcelain, and copper- and iron-ware to sell back home. Amazing skirts, raincoats, cloaks, and other garments made of colorful feathers were created for Tang royalty, aristocrats, and soldiers in such numbers as to drive some birds almost into extinction, according to the official New Tang History written in Song times.7 Trade in luxury goods flourished in Tang times.

With these prestige goods, music, games, and elaborate rituals, as well as the foreign merchants, monks, and others who visited and settled there, Tang created a court and capital so rich and appealing that members of the aristocratic elite flocked there from north and south. They left their family estates to be managed by others, eager to serve in the central government, and reluctant to leave the exciting capital. Of course, they had to serve as officials all over the empire, but reluctantly. Official postings south of the Yangzi River, not to speak of the far south around Guangzhou, were used as punishments. Such exile might easily kill a northerner not used to the heat and to malaria. The only thing that could make up for it were the fabulous fortunes to be made by milking the vibrant and lucrative overseas trade there.