1.2: Washington – Our Native American Heritage

- Page ID

- 23580

How the first people of Washington governed themselves

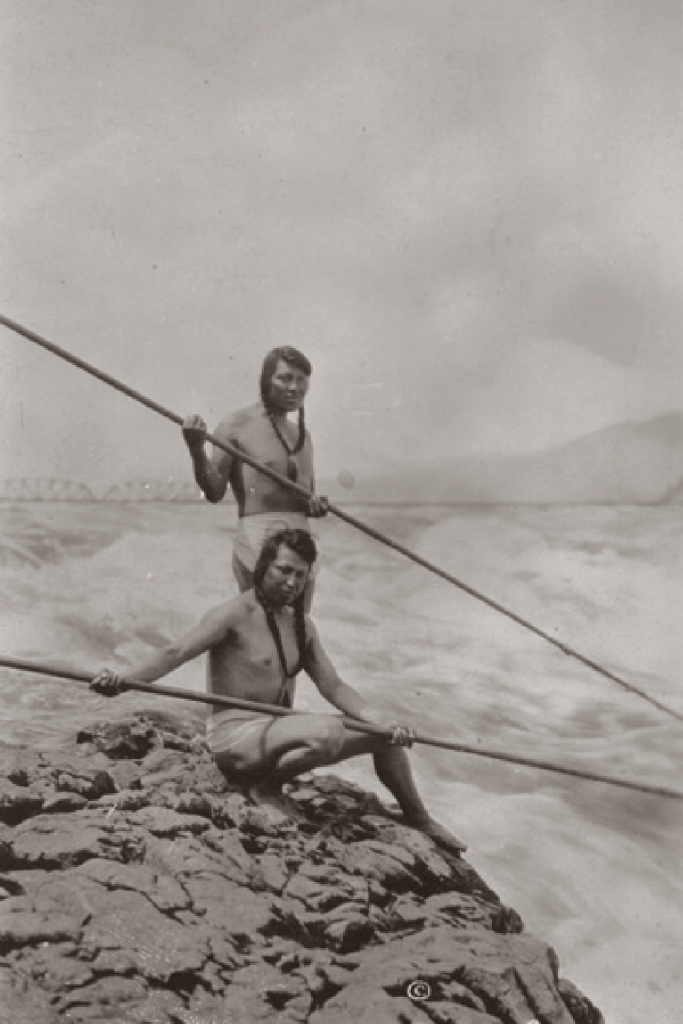

In the long march of history, “Washington” is a recent creation. For thousands of years before white settlers came, native people lived in this part of the world without creating the boundaries that define our state today. The pattern of their lives was shaped by the natural world – by where the rivers flowed, where the berries grew, and where the best fishing spots were located.

Washington’s first people didn’t plant crops or build factories; they fished, hunted, and gathered wild plants for food. They made their homes, their clothing, and everything else they needed from the materials that nature provided. They knew how to harvest fish without harming future fish runs. They knew how to burn prairie lands to keep them open, so that the camas plant whose roots they ate would flourish. They managed the natural world, but they also considered themselves part of it.

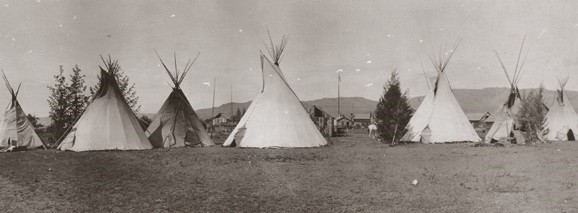

During the spring and summer, they often traveled and built summer camps where the best berries or the best hunting was. In the winter, they returned to their winter houses or longhouses, where they spent more time indoors, making baskets, clothing, and other necessities, and telling stories around the fire.

Throughout the year, native peoples held special ceremonies to show their appreciation for the bounty that nature provided. They honored the spirits of the fish, the trees, the sun and moon. This powerful connection to the spiritual nature of life was a source of strength and unity.

There were important differences between people on the east and west sides of the Cascades – just as there are today. Much of the east side of the state is drier, more open land, and the climate is hotter in the summer and colder in the winter than the rainy, more heavily forested west side of the state. As you might expect, the people who lived near the coast or around Puget Sound ate more seafood – clams, oysters, and even whale meat, than people who lived on the other side of the Cascade Mountains. People in different areas also spoke different languages. What all Washington’s first people had in common, though, was that they were very good at catching and preserving salmon. Wild salmon were extremely important to all of Washington’s first peoples.

Even though Washington’s original cultures and traditions were shaped by differences in climate and location, the way people governed themselves was similar. They didn’t write things down, so everything they did involve a lot of talking – and a lot of careful listening. In fact, listening was a very highly-developed skill. Adults taught young people the rules of good behavior by telling stories that gave specific examples of what happened when a person didn’t behave the way they should. Young people learned by listening, and by really thinking about what they heard.

When a band or tribe needed to make a decision, they gathered around and talked about what to do. If there was a disagreement, people continued to talk about it until they found a solution everyone could agree on. This is called governing by consensus.

Sometimes it would take a very long time to reach consensus on a decision, but it was more important for everyone to agree than to make a decision quickly.

Most groups of people had different leaders for different purposes. For instance, one person might be the leader for a hunting trip, but a different person might take the lead in deciding where to build a village. If someone was needed to represent the group in dealing with another tribe (or with white explorers or settlers), that might be yet another person. People mostly looked to elders for leadership, because they had more experience and wisdom. In fact, elders were honored and held in high esteem.

Sometimes, certain families provided certain kinds of leadership for many generations.

In these societies, no one owned land; that idea never occurred to them. They didn’t have hard and fast definitions of who was a member of which tribe, either. They had networks for trading and visiting each other, and people from one band or tribe often married into another. Although each tribal group had its own traditions, its own general territory, and its own ways of doing things, there was plenty of exchange that kept people from becoming isolated.

Tribal societies in Washington were radically changed by the coming of white settlers in the middle of the 1800s. In just a few years, the settlers, backed by the

U.S. government, took over most of the state and signed treaties with native peoples that required them to give up most of their land. In the place of tribal self-government, the U.S. government asserted its authority.

The traditional ways Washington’s people lived and governed themselves were changed forever. But the traditions of Washington’s first peoples weren’t lost. Even though many of the Indians’ spiritual and ceremonial practices were banned for many years by the new settlers’ government, they were kept alive, often in secret. On reservations and in Indian communities around the state, those traditions continue to be passed from one generation to the next. Today, many tribes blend ancient traditions with modern ways of governing. Indians often credit their deeply spiritual traditions with giving them the strength to survive the overwhelming force of white settlers, and the many twists and turns of U.S. policy towards native peoples.

Today, Indian self-government, traditions, and culture are experiencing a dramatic comeback. A series of court decisions and changes in national and state policy have affirmed the rights spelled out in the treaties and stimulated the growth and development of tribal self-determination. These decisions were won by many years of determined effort by Indian people and their allies. Today, tribal governments are growing, changing, and taking on important new roles and responsibilities. Tribal governments have become more and more important not just to Indians, but to all of us, because they are involved in issues such as saving wild salmon, protecting the health of rivers and streams, managing urban growth, improving education, and creating jobs.

Creating Washington’s government

Starting in the 1840s, settlers from the East and Midwest began to come to the Oregon Territory in search of land to farm, adventure, and the opportunity to create new communities. At first, just a few came, but after 1846, when Britain gave up its claim to this area and the Oregon Territory became an official part of the U.S., the number of settlers multiplied every year. Most of them settled in the Willamette Valley, and they established Salem as their capital.

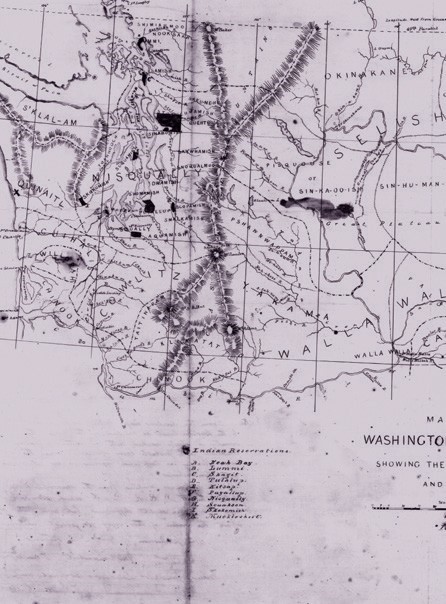

From tribal lands to territory to Washington state the story in maps

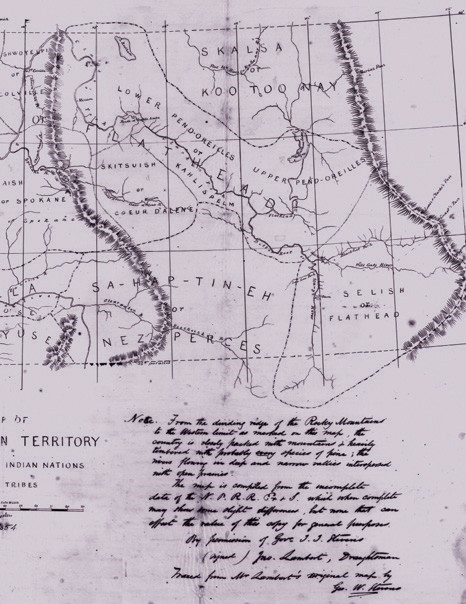

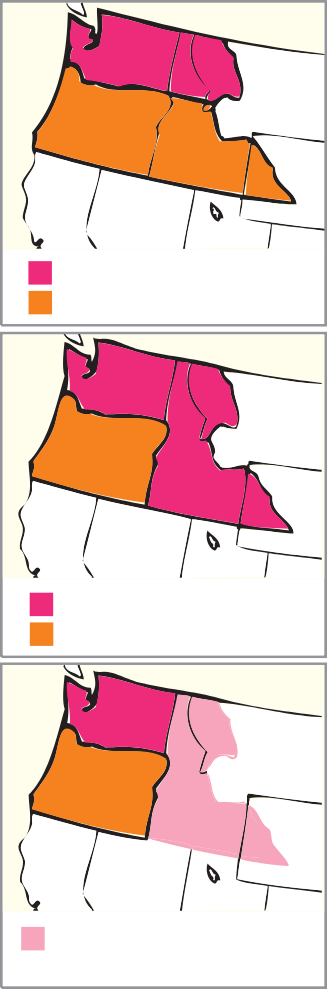

The large map, drawn in 1854, shows what early explorers knew about Washington’s land and tribes.

The maps below show how the borders of Washington changed when it became a territory in 1853, when Oregon became a state in 1859, and again when Idaho became a separate territory in 1863. The borders established in 1863 stayed the same when Washington became a state in 1889.

George Washington Bush

George Washington Bush was among the first settlers who, in 1846, helped found the community that eventually became our state’s capital. He was a free African-American who had been a very successful farmer in Missouri. He and his Irish-American wife, Isabella, decided to move to the Oregon Territory to escape from the racial prejudice of the South.

Drawing courtesy The Office of The Secretary of State

However, when they arrived in Oregon, the Territorial Legislature had just passed a “Lash Law” that subjected any African-Americans or other people of color to being whipped if they tried to settle there. So the Bush family and the friends they were traveling with decided to come north of the Columbia River, where the laws were not enforced. The Bush family settled on what is now called Bush Prairie, just south of the present- day city of Olympia.

Local tribes and the Hudson’s Bay Company helped the settlers survive their first winter. In the years that followed, the Bush family was famous for generosity to their neighbors and to new settlers, and for their hard work and skill at farming. Isabella was a nurse, and her medical knowledge was of special value to both settlers and Indians.

The federal government gave white settlers land, but excluded people of color. So when the first Washington Territorial Legislature met in 1854, they passed a resolution asking the federal government to make an exception for the Bush family. In 1855, the U. S. Congress passed “An Act for the Relief of George Bush, of Thurston County, Washington Territory,” granting this request.

George Bush’s son, Owen Bush, was elected to the Washington legislature in 1889. He introduced the legislation that created the college that is now known as Washington State University in Pullman.

But some came to what is now western Washington, and by 1851, they were campaigning to make the land north and west of the Columbia River a separate territory. From the new settlements in Seattle and Olympia, it took at least three days to get to Salem, and people didn’t feel the Salem government really represented them. So the settlers in what is now Washington called meetings, published newspaper articles, and asked Congress to declare the area north and west of the Columbia River a separate territory. In 1853, their wish was granted, even though there were only about one thousand settlers north of the Columbia. Congress also made the territory much larger than they had asked by adding land to the east of the Columbia River (see maps).

In 1854, U.S. President Franklin Pierce sent Isaac Stevens to be the governor of Washington Territory. Territories were controlled by the federal government, so the governor worked for the President of the United States.

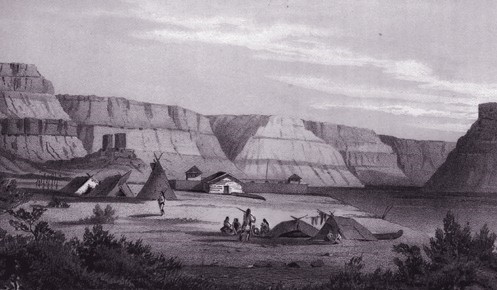

The President wanted Isaac Stevens to negotiate treaties with all the Indians who lived in the Washington Territory. The purpose of the treaties was to persuade the Indians to give up most of their lands, so that more white settlers could come and live here, and so that the federal government could grant them clear ownership of the land. From 1854-1856, Isaac Stevens traveled all over the state, and persuaded tribes to sign treaties in which the Indians promised to live on reservations, which were specific pieces of land reserved for them. In many cases, this meant the tribes had to relocate; that is, they had to move from where they usually lived. The tribes were promised small payments for the land they gave up, and they were promised that they could continue to fish, hunt, and gather in their “usual and accustomed places.” They were also promised government services such as health care and education.

The white people who wrote the treaties thought that Indians should settle down, learn how to farm, and live like white people. This didn’t make much sense to the Indians, who had been fishing, hunting, and moving around freely for thousands of years.

Isaac Stevens and the people who worked for him didn’t know very much about the Indians and their way of life, and they didn’t take the time to learn, because they were in a hurry to get treaties signed and get all the Indians grouped together on reservations.

There were brief wars between some of the Indians and the federal government over the terms of the treaties. The federal government won.

Within the next few decades, Washington began to fill up with settlers. These settlers wanted Washington to become a state, because then they could form their own state government instead of having a governor appointed by the President.

Writing Washington’s constitution

In 1889, 75 men were elected to go to Olympia to write a state constitution. For Washington to become a state, a constitution had to be written and voters had to approve it.

State constitutions are similar to the U.S. Constitution, but not exactly the same. Like our national Constitution, state constitutions set up the basic organization of government and spell out the rights of citizens. They are the foundation on which government is built. But state constitutions are usually more specific, and have more detail. For instance, our state constitution describes certain services that state government must provide – schools, prisons, and state institutions to care for people who have certain disabilities. The federal Constitution doesn’t say anything about what services our national government must provide.

State constitutions can also differ from our national constitution in the rights they give to citizens. For instance, Washington’s constitution has stronger protections of people’s privacy, our right to own guns, and stricter separation between religion and government.

Among the people (called delegates) who wrote our constitution there were 22 lawyers, 19 farmers or ranchers, nine storeowners or bankers, six doctors, three teachers, and three miners. There were no women in the group because women didn’t have the right to vote, except in elections for local school boards. There were also no Indians. At that time, Indians were considered citizens of Indian nations, not citizens of the United States. There were also many Chinese immigrants in Washington, most of whom came here to work in the mines and help build the railroads, but they weren’t allowed to become citizens, so they weren’t represented either.

Starting on the 4th of July, 1889, the 75 men set to work. They didn’t start from scratch. They copied parts of the constitutions of other states, and some sections from an earlier draft of a Washington state constitution that had been written in 1878.

Article I, Section 1 of Washington’s state constitution:

All political power is inherent in the people, and governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, and are established to protect and maintain individual rights.

Big Debates

They had big debates about many issues. For example, they had a long argument about whether the constitution should give women the right to vote. Some thought women should be allowed to vote, but they were afraid that if they said so in the constitution, the voters would reject it, and that would delay Washington becoming a state. Others didn’t want women to have the vote because they were afraid women would vote to outlaw alcohol. Companies that made beer and whiskey lobbied to keep women from getting the vote. In the end, the writers of the constitution decided not to put women’s suffrage in the constitution. They put it on the ballot as a separate measure, and it was defeated by the all-male voters.

When the legislature ran out of stationery in 1877, a resolution was written on a shingle.

The delegates who wrote the constitution also argued about the power of railroads and other big companies. The opening of the railroads in the early 1880s caused a huge population explosion. Railroads opened the state to more settlement, and made it pos- sible for the farmers and ranchers in Eastern Washington to get their products to market. But many farmers and ranchers were angry at the prices the railroads charged. A lot of people also thought the federal government had given away too much public land to the railroads, and that the owners of the railroads and other big companies had too much power and influence over government.

People didn’t want the railroads and other big businesses to get control of our state government. So the drafters of our constitution included several things to try to prevent this. They made it illegal for state government to loan money to private companies. They even forbade elected officials from accepting free railroad passes. They insisted on strict separation between private business and state government.

Tideland: land that is under water when the tide is in but not when the tide is out. Tidelands are important for several reasons: oysters, clams and other creatures we eat live there; they provide important habitat for many birds, sea creatures and plants, and tidelands provide access to the ocean (and to Puget Sound and other bays and harbors) that are important for shipping and industry. Many of the tidelands in urban areas have been filled in to make more dry land, and some have been dug up to create deeper water for boats and ships.

They also had big debates about what to do with the 2.5 million acres of land that the federal government gave to the state. Income from logging and other uses on some of this land was supposed to be used to fund schools and other public buildings. In other states, public lands had been sold off to business owners for a tiny fraction of their real value. People in Washington didn’t want that to happen here, so they wrote a strong statement that public lands must never be sold for less than they were worth. (It worked. Today, Washington’s state government still owns millions of acres of land, and logging and other activities on that land raise money to help pay for building schools and maintaining our state capitol.)

The biggest arguments, though, were over what to do about tidelands. A lot of businesses had already been established on tidelands. For instance, Henry Yesler had established a sawmill on the tidelands in Seattle. After a lot of debate, it was decided that the state would continue to own the tidelands but would lease some of them to private businesses. (At the time, the writers of the constitution didn’t think about the fact that tidelands were part of the “usual and accustomed places” that Indians had been promised rights to fish and gather clams and oysters.)

People’s distrust of powerful businesses also influenced the way our state executive branch is organized. The writers of our constitution wanted more than the separation of executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. They wanted to disperse power even within the executive branch, so that no one official would have too much power. They had seen how easily public officials could be corrupted by wealthy business owners, and they wanted to make sure that our government was honest and accountable to the voters. That’s why they created an elected Commissioner of Public Lands to protect the legacy of state-owned land. And that’s why we have nine separately elected statewide officials in our executive branch.

Agreement about education

But while the writers of the constitution disagreed about many things, there was one area where they all agreed: education. In fact, the most famous part of Washington’s constitution is this statement:

It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.

No other state has such a strong constitutional statement about the importance of public schools. Because this is such a strong statement, courts have ruled that our state legislature has to provide all public schools with enough money to pay for all students’ “basic education.” It’s up to the legislature to define what “basic education” is. (People argue about this often, because what’s “basic” changes over time. For instance, computer skills are basic to everyone’s education now, but they weren’t 25 years ago.)

The result of Washington’s definition of education as the state’s “paramount duty,” is that schools in Washington get most of their funding from the state government. In many other states, schools get most of their funding from local governments.

Also, our constitution says we must educate all children “residing” in Washington – not just those who are citizens. Originally, this was meant to protect (among others) the children of the Chinese immigrants. Today, it makes it clear that immigrants from any country can go to our public schools.

Statehood

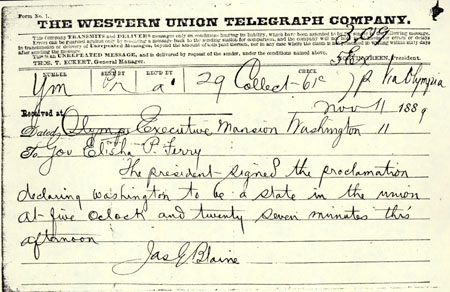

The writers of our constitution finished their work, an election was held, and the voters passed the new constitution. Then it was sent off to Washington, D. C. There was just one problem: the governor forgot to sign it. So it had to be sent back to Olympia, signed, and sent back (by train) to the nation’s capitol. Finally, on November 11, 1889, Washington became the 42nd state.

Amendments

It takes two steps to amend (change) any part of our state constitution. First, both houses of the state legislature have to pass a proposed amendment by a two- thirds majority. Second, the amendment has to be put on the ballot and passed by voters by a simple majority at the next general election. As of 2004, the constitution had been amended 96 times.

One of the most important amendments to the constitution was passed in 1912, when the initiative and referendum were added to the section on the legislative branch of government.

In 1972, another amendment was passed to ensure equal rights for women. It reads “Equality of rights and responsibilities under the law shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex.” This is called the Equal Rights Amendment or ERA. It was proposed as an amendment to our national constitution, too. But an amendment to our national constitution has to be passed by Congress and ratified (agreed to) by the legislatures of 38 states, and the national ERA never quite achieved that goal. This is an indication of how much more difficult it is to amend our national constitution than our state constitution.

Another interesting amendment was passed in 1988. Our original state constitution said we should have institutions to care for “the blind, deaf, dumb or otherwise defective youth” and the “insane and idiotic.” That language was considered normal at the time, but today we think it’s mean and insulting. Ralph Munro, who was our Secretary of State for many years, worked to pass a constitutional amendment to change it. He succeeded, and now it reads “youth who are blind or deaf or otherwise disabled”; and “persons who are mentally ill or developmentally disabled.”

Contributors and Attributions

“This resource was adapted from Chapter 1 of The State We’re In: Washington (8th edition, 2018) developed by the League of Women Voters of Washington Education Fund. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.”