8.1: The Rise of Los Angeles- Twentieth-Century Metropolis

- Page ID

- 127009

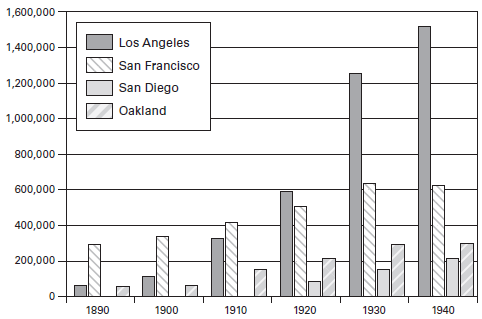

The 1920 census recorded that Los Angeles had passed San Francisco in population, becoming the 10th largest city in the nation. LA was, in fact, the fastest growing major city in the country during the early 20th century. Figure \(8.1\) on the next page presents population patterns among the largest cities in California between 1890 and 1940. During the 1920s, LA doubled in size—by 1930, it ranked fifth in the nation in size and continued to grow in the 1930s.

The Economic Basis for Growth

LA’s spectacular growth began in the 1880s, when competitive railroad passenger rates from the Midwest and South combined with the sunny climate and a romanticized version of California history to attract health seekers and tourists. The development of refrigerated railroad cars and ships in the 1890s contributed to a boom in citrus growing. LA boosters secured massive federal funding to construct a port at San Pedro. The Owens River began to flow into the LA water system in 1913, providing much more water than the city then needed, and later projects expanded water supplies in advance of need. The availability of water permitted growth, and other factors contributed to the emergence of a diversified economy. During the 1920s and 1930s, three elements contributed to the city’s growth: the motion picture industry, oil discoveries, and a variety of manufacturing enterprises.

Figure \(8.1\) Population of Major California Cities, 1890-1940

This graph shows the dramatic surge in the population of Los Angeles over the 50 years between 1890 and 1940. Though the population of San Francisco doubled during those years, the other three cities grew much faster. What factors help to account for the spectacular growth of Los Angeles during this period?

By World War I, the motion picture industry was the most prominent industry in southern California. Los Angeles was a natural for making movies—the weather was usually sunny, it rarely rained, and a variety of natural scenery existed nearby, including ocean, mountains, and desert. By 1914, Hollywood, a suburb of Los Angeles, had become the center for moviemaking. By the mid-1930s, the industry was dominated by a few large studios, notably Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM, formed in 1924), RKO (1928), Warner Brothers (1929), 20th Century-Fox (1935), and Paramount (1935). These studios competed to lock up actors and directors in long-term contracts and to promote their own “stars.” Movies became big business, dependent on New York banks for capital to construct huge physical plants and to deploy the latest technology of light and sound. By 1937, moviemaking was the fourth largest industry in the nation. And, by then, eight corporations produced 90 percent of all films and controlled both distribution of the films and many movie theaters.

A second factor in the growth of LA was oil. Major oil discoveries in the LA basin in the early 1920s boosted California to first place among oil producing states during the 1920s. Discoveries in 1920 and 1921 at Huntington Beach, Long Beach, and Santa Fe Springs set off a speculative mania—as one observer put it, everyone went “stark, staring oil mad.” A geologist called it “the greatest outpouring of mineral wealth the world has ever known.” In 1924, oil passed agriculture as the state’s leading industry. By 1930, the LA basin held 32 refineries employing 5000 people.

A third factor in LA’s growth was manufacturing. In the early 1920s, the nation’s three largest tire companies all separately concluded that they should build plants in Los Angeles—its port was convenient for shipping rubber from Southeast Asia, it was close to newly developed cotton fields (cotton cord was the other major ingredient in making tires), and it was in the center of the most rapidly growing market for tires. LA could also promise to meet the plants’ heavy demands for water. Similar reasoning led Ford to locate an automobile assembly plant in the LA basin and steelmakers to open a plant in Torrance. At the same time, the LA basin remained a major agricultural region, producing crops for food-processing plants. Between 1919 and 1930, LA moved from 28th to ninth place among American manufacturing cities. By 1930, however, LA ranked fifth in population, so manufacturing did not dominate the city’s economy in the same way that it did in Detroit or Pittsburgh, where a third to a half of the work force was in manufacturing. In LA, the proportion was a bit over a quarter.

The growth of LA was not affected by one of the state’s greatest disasters, the collapse of the St. Francis Dam. Built in San Francisquito Canyon in 1924–26 to create a reservoir for water from the Owens River, the dam filled to capacity on March 7, 1928. It collapsed on March 12, sending a torrent 125 feet high down the canyon, destroying everything in its path. The huge wave then followed the Santa Clara River channel through Ventura County and into the Pacific Ocean, carrying debris and victims with it. The official death toll was 385, but current estimates are as many as 600, making it second only to the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 as California’s deadliest disaster. The collapse of the dam badly damaged the reputation of William Mulholland (pp. 218–220), and he soon retired from the LA water department that he had done so much to create.

The Automobile and the Growth of Southern California

The rapid growth of Los Angeles came just as the automobile industry was promoting the notion of a car for every family. By 1925, LA had one automobile for every three residents, twice the national average. The LA basin also had an excellent streetcar system. The auto and the streetcar made it possible for Angelenos to live further from work than ever before. At the same time, realestate developers busily promoted the ideal of the single-family home. By 1930, 94 percent of residences in Los Angeles were single-family homes—something unprecedented for a major city—and Los Angeles had the lowest population density by far among the nation’s 15 largest cities.

Life in Los Angeles came to be organized around the automobile to an extent unknown in other major cities, where most growth and construction had taken place in the era of the horse and the streetcar. The experience of LA set the pattern for future urban development nearly everywhere else. The first modern supermarket, offering “one-stop shopping,” appeared in LA. The “Miracle Mile” along Wilshire Boulevard was the nation’s first large shopping district designed for the automobile. The Los Angeles Times put it this way in 1926: “Our forefathers … set forth ‘the pursuit of happiness’ as an inalienable right of mankind. And how can one pursue happiness by any swifter and surer means … than by the use of the automobile?”

Promoters attracted hundreds of thousands of new residents to southern California by presenting images of perpetual sunshine, tall palm trees lining wide boulevards, gushing fountains, and broad, sandy beaches. The rapid growth of the economy and the population also attracted many who hoped to

Grauman's Chinese Theater is perhaps the most famous movie theater in the United States. It opened in 1927, and its architecture and interior décor were even more exotic than most theaters of the day. Why do you think that movie theater owners wanted theaters with unusual, even bizarre, architecture and ornament?

profit from the unsettled society, and the LA basin acquired a reputation as a center for get-rich-quick schemes, bizarre religious cults, and unusual political groups. Carl Sandburg, in the late 1920s, wrote that “God once took the country by Maine as the handle, gave it a good shake, and all the loose nuts and bolts rolled down to southern California.”