7.4: Marriage

- Page ID

- 68367

Same - Sex Marriage was first publicized in an August 1953 cover story in ONE Magazine. That story resulted in the confisca- tion of the issue by postal authorities, who deemed the topic of same-sex marriage as a violation of obscenity statutes. In the gay liberation movement of the early 1970s, several same-sex couples applied for marriage licenses, but were universally denied. Legal challenges were similarly defeated.

The prohibition of gay and lesbian people from marriage had ramifications beyond the institu- tion itself. It meant that same-sex partners of hospitalized LGBTQ people could be denied visitation and decision-making power. The death of an LGBTQ person left the surviving partner without any of the benefits granted to married couples. Lengthy legal battles were often required to recognize the survivor’s rights in housing, inheritance, and child custody. Same-sex partners were barred from tax and insurance benefits. American citizens could not keep non-citizen same-sex partners from being deported. Same-sex partners could be excluded from adopting. LGBTQ status could be used to dismiss the custody claims of separated gay or lesbian parents.

In 1996, the Hawaii State Supreme Court ruled that the state could not legally deny same- sex couples the opportunity to marry. Although Hawaiian voters approved an amendment prohibiting the implementation of same-sex marriage, the court’s decision ignited a backlash across the nation. By the end of 1996, sixteen states had implemented laws banning same-sex marriage, and the federal government had passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). DOMA denied same-sex couples the federal benefits and rights of marriage, even if a state legally recognized the union.

In 2000, Vermont passed the nation’s first civil unions law, which conferred upon same- sex couples all the state’s rights and benefits of married heterosexual couples. In 2004, the Massachusetts State Supreme Court ruled that the prohibition of same-sex marriage was unconstitutional, and the state became the first to officially recognize gay and lesbian marriages. In reaction, twenty-two more states instituted legislation banning same-sex marriage. An amendment to the United States constitution to ban same-sex marriage was proposed but defeated in 2004 and 2006.

Between 2004 and 2012, only six more states legalized same-sex marriage. Then from November 2012 to December 2013, 11 more states legalized same-sex marriage, bringing the total to 18. When Thea Spyer died in 2009, Edith “Edie” Windsor, her partner of over 40 years, was denied the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses because of DOMA and was sent a tax bill for $363,053. She sued, and in 2013, the United States Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Windsor that DOMA was unconstitutional, thereby granting same-sex married couples the same federal rights as heterosexual couples.

By 2015, multiple challenges to state bans on same-sex marriage had made their way through the court of appeals, with four rulings against the ban, and one upholding the ban. Consolidating the cases under Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave same-sex couples the right to marry across the United States. The ruling over- turned all state bans on same-sex marriage and granted all gay and lesbian United States citizens the right to marry regardless of where they lived.

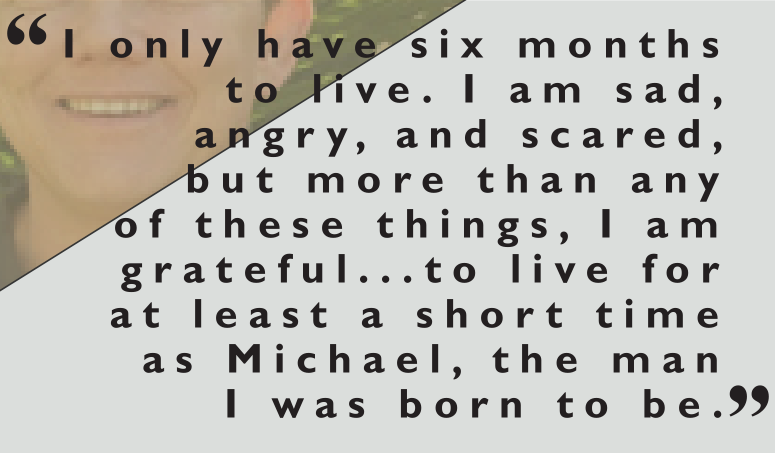

I came out as a lesbian at nineteen, before coming out as transgender at thirty-two. Telling people you’re a transman takes a whole different type of courage. While I ached for the love and support of my family, it was not to be. The good news is that the LGBTQ community embraced me, creating a new and more meaningful family of queer kinships.

Like most trans-identified men, I was socialized to adhere to female gender norms. Thus after coming out, I was constantly questioning my gender expression. Am I trans enough? Am I enough of a man? What makes a man a man? But I learned that I am a man simply because I say I am and I get to choose how to express my gender. Like sexuality, gender identity is fluid. It constantly evolves and each of us must find his or her authentic self in a hodgepodge of deeply ingrained stereotypes and expectations.

On August 13, 2014, I was told that due to brain cancer, I only have six months to live. I am sad, angry, and scared, but more than any of these things, I am grateful. I am grateful that my dream came true and that I had the opportunity to live for at least a short time as Michael, the man I was born to be.

– Michael Saum