3.2: Politics

- Page ID

- 68331

THE MONTH AFTER THE 1969 Stonewall Riots, LGBTQ activists in New York City formed the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). The group capitalized on a newly energized community to introduce a radical activism into the gay rights movement. At its height, GLF had over 50 chapters across the United States, each initiating boycotts and protests against the discriminatory policies of local police, universities, businesses, and city governments. Although its unstructured organization and conflicting goals would quickly doom the group, GLF forever changed the LGBTQ movement. GLF members were responsible for launching gay pride marches, community service centers, and many of the era’s leading LGBTQ activist organizations.

The Gay Activists Alliance, a splinter group from the GLF in New York, introduced “zaps,” a non-violent, direct-action protest in which activists directly and publicly confronted politicians, celebrities, and businesses. These in-your-face protests forced their targets to address the issues of the LGBTQ community or risk continued public attacks. As more activist organizations adopted these increasing aggressive tactics, some elected officials and candidates for office at the local, state, and federal level began to publicly address the topic of gay and lesbian rights for the first time.

In San Francisco in 1971, Jim Foster founded the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, the first registered LGBTQ political club in the nation. Soon LGBTQ political organizations could be found in most major United States cities, forcing politicians to address the LGBTQ community in local, state, and national elections. In 1977, the Municipal Elections Committee of Los Angeles (MECLA) became the first openly LGBTQ political action committee in the nation. Although initially founded to influence city politics, MECLA’s fundraising power expanded its influence into state and national politics. The organization quickly became the most powerful LGBTQ political group of its time.

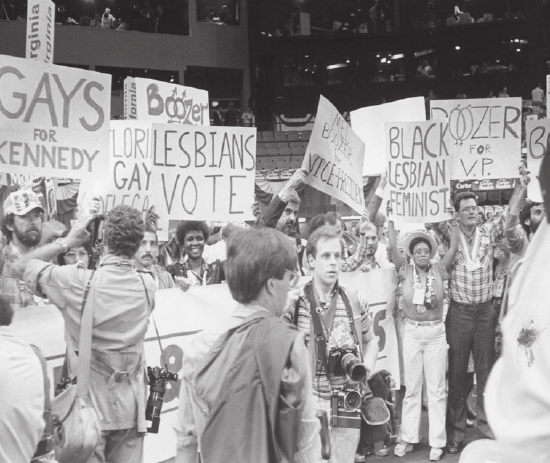

With increasing political clout, gay and lesbian politicians and delegates began vying for political positions and offices. The 1972 Democratic Convention boasted the first openly gay and lesbian delegates. Two of the delegates, Jim Foster and Madeline Davis, spoke at the podium, the first LGBTQ people to do so at a major political function. By the 1980 Democratic Convention, the gay and lesbian contingent had grown to seventy-seven delegates. At that convention, the Democratic Party officially endorsed its first ever gay rights plank.

In 1974, Kathy Kozachenko became the first openly LGBTQ person elected to a government office when she won a seat on the Ann Arbor City Council in Michigan. Elaine Noble won a seat in the Massachusetts state legislature later in the year, becoming the first openly LGBTQ state representative. Minnesota State Senator Allan Spear came out as gay at the end of 1974 and then won his re-election bid in 1976, becoming the first openly gay man to be elected to government office.

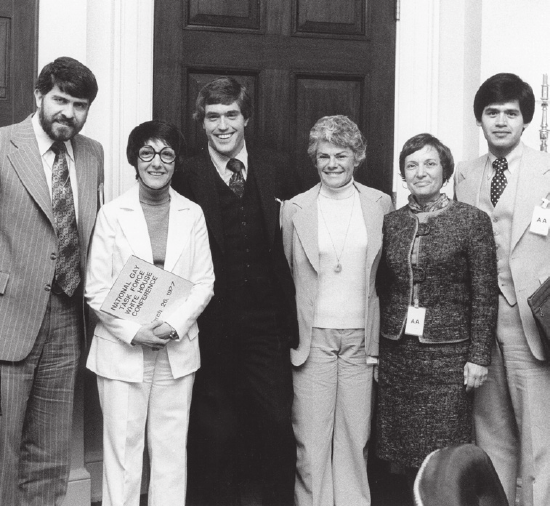

In 1977, the National Gay Task Force (NGTF) collaborated with Midge Costanza, Assistant to the President for Public Liaison, on a meeting of gay and lesbian activist leaders at the White House. President Carter had not been informed of the meeting, and LGBTQ leaders would not meet with a sitting president until 1993. However, the event implied federal recognition of the gay rights movement and opened the door for future NGTF meetings with federal government agencies. By 1977, gay and lesbian activists had begun meeting with representatives of the American Civil Liberties Union and various women’s rights groups to discuss common strategy. However, prejudice against LGBTQ people still trumped the promise of a broader collaboration; the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights rejected NGTF’s application for membership.

WHEN ELAINE NOBLE CAME OUT, her lover left her, she lost her job as an advertising executive, her tires were slashed, and she got obscene phone calls. So what did she do? She ran for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Winning 59% of the vote, she was the first openly LGBTQ person elected to state office. Not only that, she was reelected two years later. In this photograph, she talks with future United States Congressman Barney Frank, who came out himself in 1987.

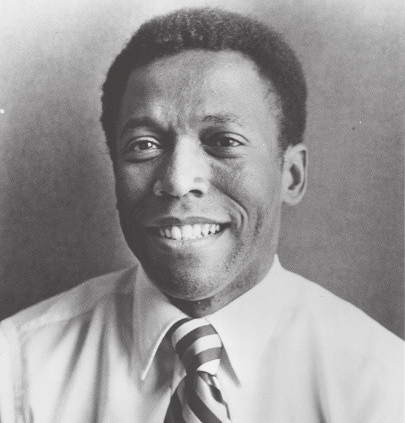

MELVIN BOOZER WAS A SOCIOLOGY PROFESSOR at the University of Maryland and president of Washington’s Gay Activists Alliance. He was little known outside of Washington, D.C. when he approached the podium to deliver one of the most powerful speeches of the 1980 Democratic Convention. “Would you ask me how I dare to compare the civil rights struggle with the struggle for gay and lesbian rights? I can compare them and I do compare them, because I know what it means to be called a nigger and I know what it means to be called a faggot, and I understand the difference, in the marrow of my bones. And I can sum up that difference in one word: None.”

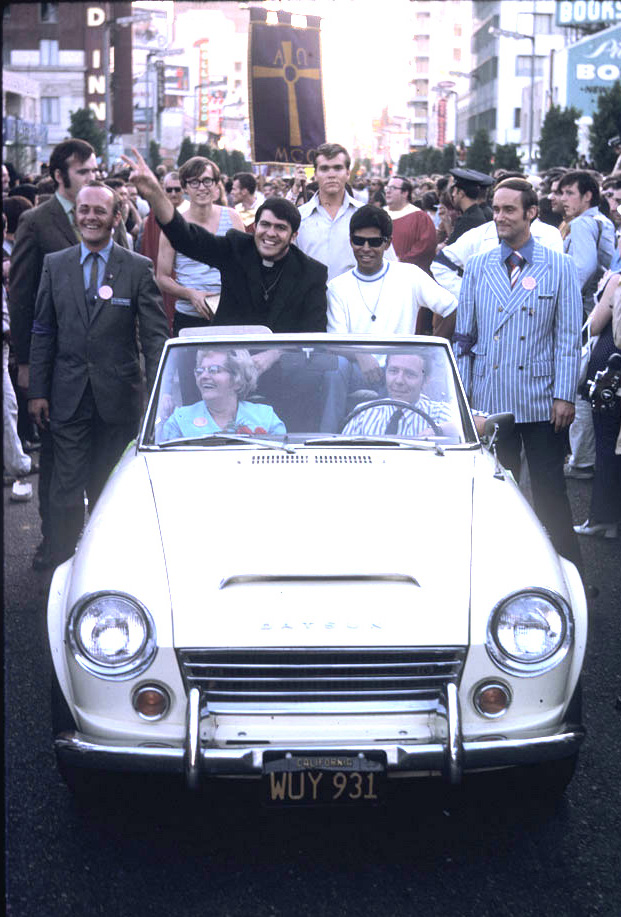

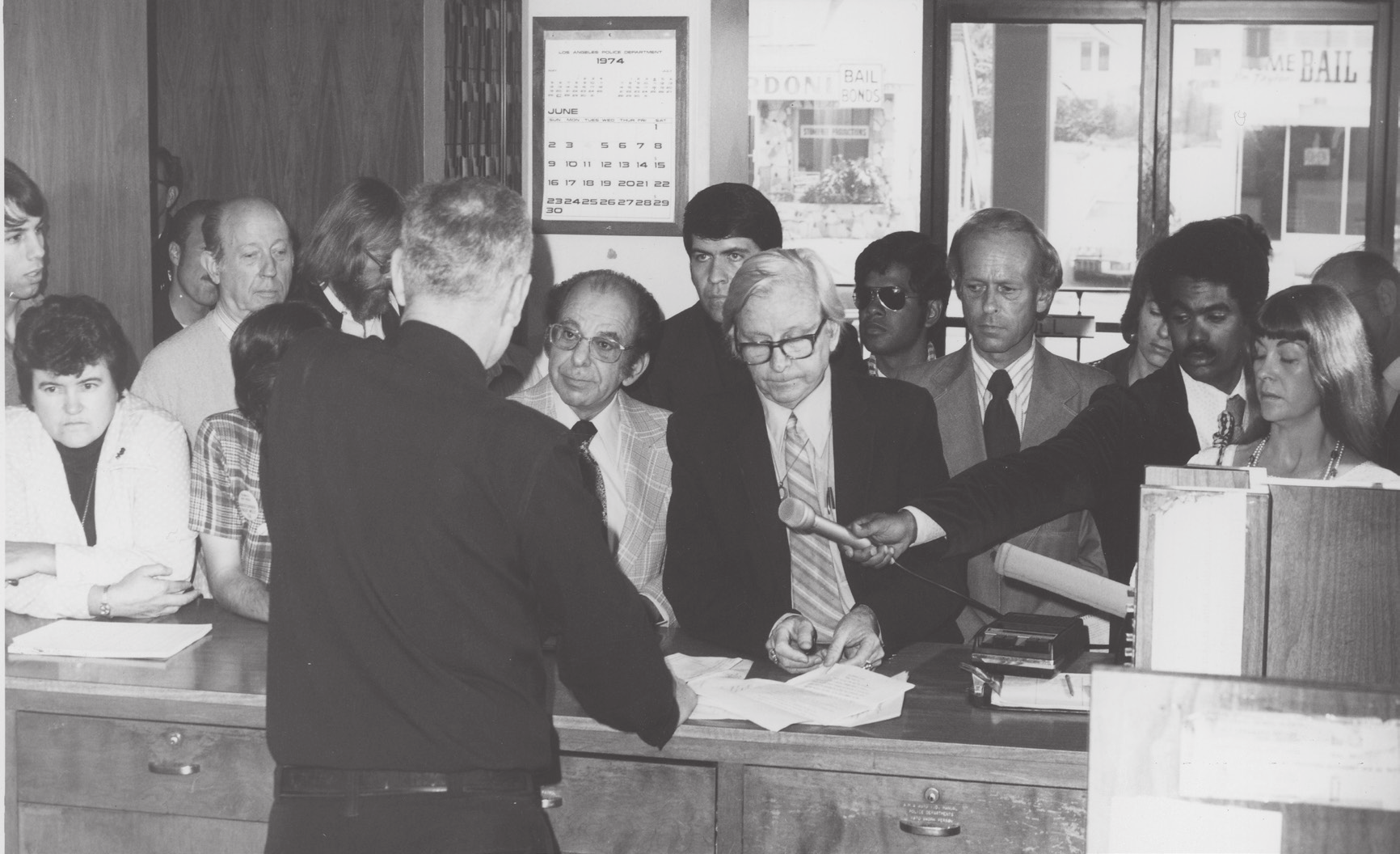

IN 1966, IVY BOTTINI BECAME A FOUNDING member of the National Organization for Women (NOW), and soon after, the New York chapter’s second president. When she divorced her husband in 1968 and news of her being a lesbian became public knowledge, some NOW members spoke out against her, using the term “lavender menace” to describe the danger of lesbians in the women’s movement. Bottini left NOW and relocated to Los Angeles, where she became a leader in the gay and lesbian rights movement. She helped lead the No on Briggs Proposition 6 campaign (the proposition intended to fire gay and lesbian educators from public schools), the Stonewall Democratic Club, and the Los Angeles Police Department’s first Gay and Lesbian Police Task Force. She responded to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s by founding the Los Angeles AIDS Network and becoming a founding member of AIDS Project Los Angeles.