2.1 The Beginnings of the Modern LGBTQ Rights Movement

- Page ID

- 68353

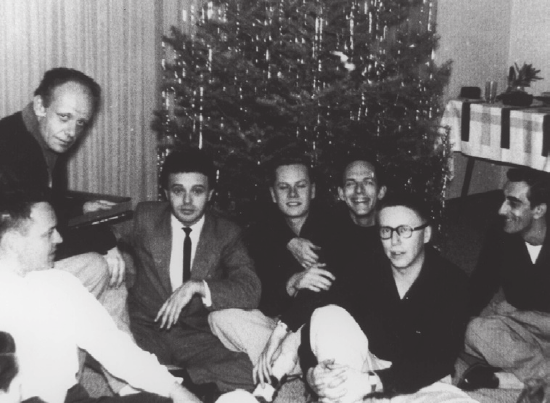

THE POST WORLD WAR II ERA saw the formation of some of the nation’s first LGBTQ organizations, including the Veterans’ Benevolent Association in New York and Knights of the Clock in Los Angeles. Although these early organizations had no real impact on LGBTQ rights and mobilization. The first LGBTQ activist organization of note came together in 1951 when Harry Hay helped organize the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles. The Mattachine Society blamed an intolerant society, not gay and lesbian people, for the discrimination they faced. Hay argued that gay and lesbian people were a minority group oppressed by a prejudicial society, and they needed to organize to challenge their unjust persecution.

At first, membership in the organization grew slowly. Most gay and lesbian people feared they would be arrested or fired from their jobs if anyone knew they were a part of an LGBTQ organization. But in 1952, when the Mattachine Society success-fully defended a police entrapment case against one of its members, excitement spread about the organization. Mattachine Society chapters formed across the United States and membership expanded rapidly. The success was short-lived. At the Mattachine Society’s national convention in 1953, members forced Hay and the other original founders out because of their past communist ties. Although the following years saw membership dwindle and the national coalition crumble, local Mattachine Societies in Washington D.C., New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit among others continued to work effectively for gay and lesbian rights into the 1970s.

IN AN ERA THAT LABELED LGBT PEOPLE as mentally ill and legally criminal, Latino gay activist José Julio Sarria provided a public symbol of pride, determination, and revolt. Sarria’s theatrical drag performances at the Black Cat bar in San Francisco were a popular theatrical attraction in the 1950s and 1960s. When he was arrested on a morals charge, he decided “to be the most notorious impersonator or homosexual or fairy or whatever you want to call me—and you would pay for it.” His lyrics taunted the police who harassed him. He took to the streets in makeup and drag in an open challenge to local morals statues. He led the bar’s patrons in renditions of “God Save Us Nelly Queens,” enlisting them in the war against quiet shame and solitude.

Sarria ran for a city supervisor’s seat in 1961, the first openly LGBTQ person to run for government office in the United States. Later as founder and head of the drag-based Imperial Court System, Sarria created an oasis for LGBTQ pride and celebration, as well as a fundraising force for LGBTQ rights causes across the United States. “You do good work, your work will fight your battles.” Jose Sarria’s work cast him as one of the most caring, devoted, and fearless leaders in the early fight for LGBTQ rights.

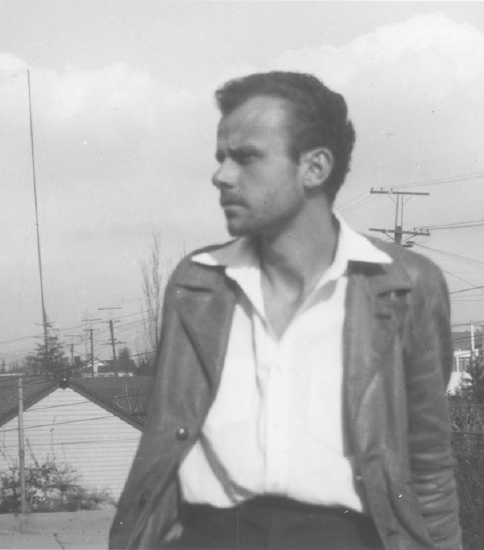

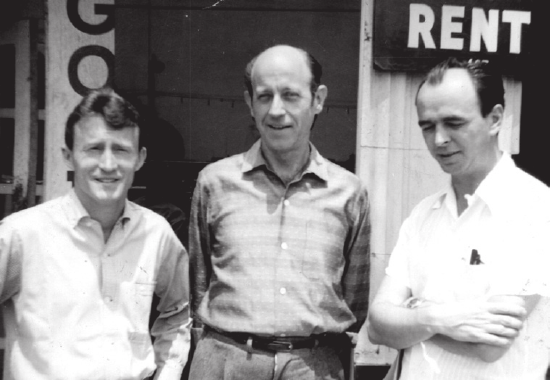

HARRY HAY JOINED THE COMMUNIST PARTY in the 1930s, but soon grew weary of the party’s anti-homosexual stance. In 1948, he proposed a group founded on the idea that homosexuals were an oppressed minority who must mobilize for civil rights. Two years later, Hay and four others founded the Mattachine Society.

Hay ended his marriage, resigned from the Communist Party, and dedicated himself to the Mattachine Society. Unfortunately, Hay’s hope of leading a national movement ended when he and his fellow co-founders were ousted due to their past communist ties. After being called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in Los Angeles in 1955, Hay retreated from public activism.

In the 1970s, Hay and his partner John Burnside became active in the gay and Native American civil rights movements. By the end of the de- cade, they had helped found the Radical Faeries, a tribal spiritual movement for building gay consciousness. Hay’s reintroduction into LGBTQ activism revived interest in his past and early organizing efforts and led to his standing among many as the founder of the gay rights movement.

In 1953, a group of Mattachine Society members in Los Angeles came together to publish the LGBT periodical, ONE Magazine. Henry Gerber in 1924, and Lisa Ben in 1947, had

each published short-lived gay and lesbian periodicals, but ONE Magazine was the first to sustain production and reach a national audience. ONE Magazine challenged the status quo with cover stories on same-sex marriage and federal anti-LGBTQ persecution. The magazine quickly drew the attention of the FBI and the United States Post Office. In 1953 and again in 1954, the local postmaster confiscated the magazine, claiming its positive portrayal of homosexuality violated federal obscenity laws. But in the 1958 decision ONE, Inc. v. Olesen, the United States Supreme Court overturned the ruling, delivering the first Supreme Court decision in favor of LGBTQ rights.

In 1955 San Francisco, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon helped found the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian organization in the United States. Their publication, The Ladder,

would be the only lesbian periodical in the United States over the next fourteen years. The Daughters of Bilitis expanded to several chapters across the United States and, in 1960, convened the first of a series of national lesbian conferences.

CHRISTINE JORGENSEN WAS NOT THE FIRST PERSON to have gender reassignment surgery, but she was certainly the most famous American to do so. A World War II veteran, George William Jorgensen always felt he was a woman trapped in a man’s body. Because the United States had no facility for sex reassignment surgery, Jorgensen had the procedure in Denmark in 1951. Now known as Christine, Jorgensen became a media sensation upon her return to the United States in the early 1950s. In an era where the mainstream media did not discuss non-cisgender identity or sexual orientation, Jorgensen broke the silence by speaking to media outlets, touring as an entertainer and lecturer, writing a book, and having a movie made about her life. Her publicity raised the consciousness and visibility of transgender people to themselves and to the nation at large.

Del Martin 1921 - 2008

FOUNDING MEMBERS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS, Phyllis Lyon (left) and Del Martin were as committed to activism as they were to each other. Aside from running the Daughters of Bilitis and its flagship publication, The Ladder, they were active in the Council on Religion and the Homosexual and helped launch the anti-police brutality Citizens Alert. They were the first lesbians to join the National Organization for Women as a couple, despite the anti-lesbian rhetoric prevalent at the time. Their book Lesbian/Woman, winner of the American Library Association’s LGBT book of the year in 1972, was a formative text for the burgeoning lesbian rights movement. Later, Martin and Lyon developed into leading educators regarding domestic violence and human sexuality. Together for over fifty years, they were the first same-sex couple legally married in California.