8.3: The Decline of the Northern Kingdom and the Rise of the Cotton Kingdom

- Page ID

- 9381

Slave labor helped fuel the market revolution. By 1832, textile companies made up 88 out of 106 American corporations valued at over $100,000.14These textile mills, worked by free labor, nevertheless depended on southern cotton, and the vast new market economy spurred the expansion of the plantation South.

By the early nineteenth century, states north of the Mason-Dixon Line had taken steps to abolish slavery. Vermont included abolition as a provision of its 1777 state constitution. Pennsylvania’s emancipation act of 1780 stipulated that freed children must serve an indenture term of twenty-eight years. Gradualism brought emancipation while also defending the interests of northern masters and controlling still another generation of black Americans. In 1804 New Jersey became the last of the northern states to adopt gradual emancipation plans. There was no immediate moment of jubilee, as many northern states only promised to liberate future children born to enslaved mothers. Such laws also stipulated that such children remain in indentured servitude to their mother’s master in order to compensate the slaveholder’s loss. James Mars, a young man indentured under this system in Connecticut, risked being thrown in jail when he protested the arrangement that kept him bound to his mother’s master until age twenty-five.15

Quicker routes to freedom included escape or direct emancipation by masters. But escape was dangerous and voluntary manumission rare. Congress, for instance, made the harboring of a fugitive slave a federal crime as early as 1793. Hopes for manumission were even slimmer, as few northern slaveholders emancipated their own slaves. Roughly one fifth of the white families in New York City owned slaves, and fewer than eighty slaveholders in the city voluntarily manumitted slaves between 1783 and 1800. By 1830, census data suggests that at least 3,500 people were still enslaved in the North. Elderly Connecticut slaves remained in bondage as late as 1848, and in New Jersey slavery endured until after the Civil War.16

Emancipation proceeded slowly, but proceeded nonetheless. A free black population of fewer than 60,000 in 1790 increased to more than 186,000 by 1810. Growing free black communities fought for their civil rights. In a number of New England locales, free African Americans could vote and send their children to public schools. Most northern states granted black citizens property rights and trial by jury. African Americans owned land and businesses, founded mutual aid societies, established churches, promoted education, developed print culture, and voted.

Nationally, however, the slave population continued to grow, from less than 700,000 in 1790 to more than 1.5 million by 1820.17 The growth of abolition in the North and the acceleration of slavery in the South created growing divisions. Cotton drove the process more than any other crop. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, a simple hand-cranked device designed to mechanically remove sticky green seeds from short staple cotton, allowed southern planters to dramatically expand cotton production for the national and international markets. Water-powered textile factories in England and the American Northeast rapidly turned raw cotton into cloth. Technology increased both the supply of and demand for cotton. White southerners responded by expanding cultivation farther west, to the Mississippi River and beyond. Slavery had been growing less profitable in tobacco-planting regions like Virginia, but the growth of cotton farther south and west increased the demand for human bondage. Eager cotton planters invested their new profits in new slaves.

The cotton boom fueled speculation in slavery. Many slave owners leveraged potential profits into loans used to purchase ever increasing numbers of slaves. For example, one 1840 Louisiana Courier ad warned, “it is very difficult now to find persons willing to buy slaves from Mississippi or Alabama on account of the fears entertained that such property may be already mortgaged to the banks of the above named states.”18

.png?revision=1)

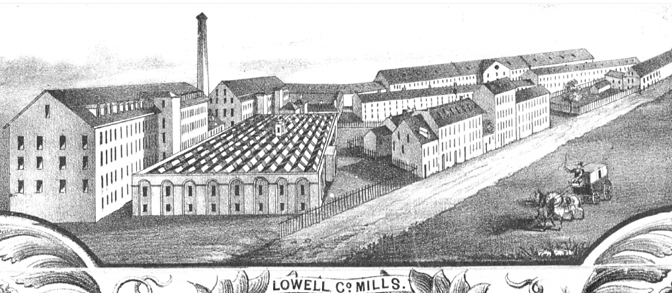

New national and international markets fueled the plantation boom. American cotton exports rose from 150,000 bales in 1815 to 4,541,000 bales in 1859. The Census Bureau’s 1860 Census of Manufactures stated that “the manufacture of cotton constitutes the most striking feature of the industrial history of the last fifty years.”19 Slave owners shipped their cotton north to textile manufacturers and to northern financers for overseas shipments. Northern insurance brokers and exporters in the Northeast profited greatly.

While the United States ended its legal participation in the global slave trade in 1808, slave traders moved one million slaves from the tobacco-producing Upper South to cotton fields in the Lower South between 1790 and 1860.20 This harrowing trade in human flesh supported middle-class occupations in the North and South: bankers, doctors, lawyers, insurance brokers, and shipping agents all profited. And of course it facilitated the expansion of northeastern textile mills.