6.1: Ideas, Audience, and Goals

- Page ID

- 50713

Phase 1: Ideas, Audience, and Goal

Getting starting on any technical writing project, you need to have a firm awareness of what exactly you’re doing and who you’re creating your final deliverable for. When we think about projects, we want to think in terms of deliverables—what will you deliver to your client(s) at the end of the day? These clients may be your boss, they may be someone outside your organization, they might be your instructor or thesis or dissertation committee in an academic context. In any case, you need to know what you want to deliver, who’s going to get it, and how you’re going about all of that.

Deliverables and audiences and goals intertwine considerably—depending on what you want to do and who’s going to be the target, what you want to create may change. For example, you might be creating content that you want to market to skateboarders for a ready reference. If you know much about skateboarders, you may know that in general they stereotypically love stickers, especially stickers that they can decorate their boards with. If you’re trying to get awareness of say, concussion symptoms, to the broader community of skaters, a cool looking sticker might make a lot of sense. That deliverable fits that community.

Sketching out Goals, Deliverables, and Audience

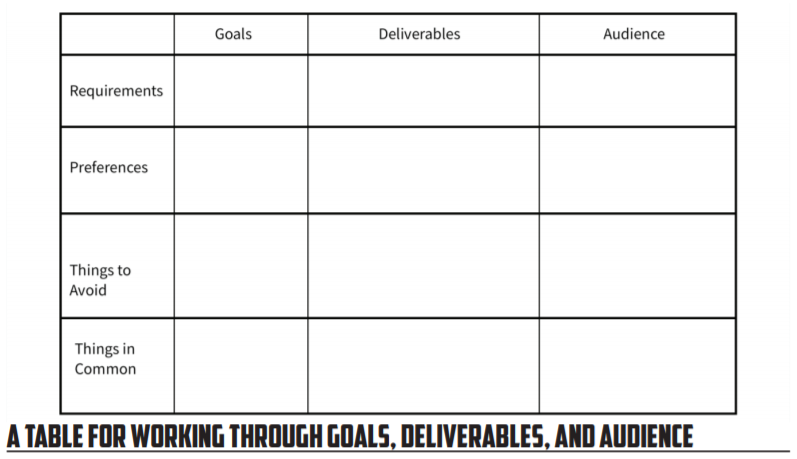

When you get started, you want to think horizontally across categories. Don’t get trapped in audience, goals, or deliverables. Think about how each of these interact and the constraints that each puts on the rest. Using something like the chart below (which can be drawn easily on a whiteboard for collaboration), figure out what the constraints are for your project:

Think about each of these sections as being a supplement to or new way of thinking about the existing writing process that we’ve discussed previously. When you work with a project, you need a broader lens than the specific writing process you may have—your projects often will transcend boundaries that individual work won’t come close to touching.

When you think about goals, think about your team’s goals, your project’s overall goals, and any goals that may exist outside of your particular team and project that may come into play (such as an organizational goal to reduce carbon emissions). For goals, think about what is going to be required, what would be preferred, and what should be avoided.

After thinking about goals, start thinking about audience—what will your audience require, what will they prefer, what will they want you to avoid (or should you avoid with this group) and what might they have in common with your goals/group? Again, this is part of the larger writing process, but you’re trying to think long-term about a large-scale project.

When you assess deliverables, you are creating a space that will bridge your goals and your audience. The deliverables are a place where each group will impact what goes on, and in many ways the deliverable is the mediation of the audience and your team’s goals. Each side has some say about what happens in this slot.

Don’t take the above as the definitive version of what will be happening in your project—think about how the above can be used to think through the project you have, giving you something to work with as you advance to your ideas phase.

The Idea Creation Process and Theming

Once you’ve got a handle on your goals, audience, and deliverables, you’ll want to start to think about the format and form of these deliverables. Knowing that you want to create something doesn’t tell you how to create that something. Just like the example we had previously of the wedding program, you often need to have an angle or a thematic that will guide what you’re going to create. The idea creation phase of things, which can happen concurrently or after you’ve assessed the audience and deliverables and goals, tries to figure out what this project can/should look like and how it can all fit together. A lot of the ideas phase can be visual design work, but don’t forget that visual design can also include the actual format and medium of your final deliverables. Large-scale projects like campaigns to build awareness for an event or issue often can contain documents of a variety of types and formats, but these documents tend to be bundled together using a cohesive theme. You see the same thing many times with university campaigns that will color the way a university presents itself for the duration of the campaign.

For example, you might be tasked with creating a public-awareness campaign about a new park that will be built in the center of town. To do this, you would need to create a variety of texts such as flyers, emails, radio spots, banners, and signage. The overall theme of your campaign would need to mesh with the visual identity of the city and attract the particular audience you’re aiming to bring into the park. For example, if the park has a central venue for hosting local concerts, you might go with the theme that “West End Park Rocks,” going with a rock-and-roll theme for all of the visuals you’ll create. You’d then want to see what this theme filters out into—how do you express rock and roll visually? Do you use a guitar outline? Do you have a band silhouette? Do you adapt the visual conventions of classic concert posters and album art? You have to figure out what the theme does when it meets the deliverables and campaign you are working with.

First off, you need a theme that you can think through. To arrive at a theme, you want to think as broadly as possible. One thing that can be useful when you’re creating a theme as a team is to find examples of content that you’re required to incorporate as well as content that you like. Create a dropbox of sorts of your ideas and examples that you can use to collect data on what you might use as a theme. If you’re designing a public information campaign like the example above, use your phone to take shots or screenshots of things that fall into that genre that have elements you like. Just like with visual conventions, you’re looking for elements that you can blend together into your own cohesive whole, your own theme.

Themes can also work with feelings and ideas—you can think about what types of ideas and feelings are associated with your project. For this, instead of creating a repository of content, you may want to start brainstorming with something like a word map. What key terms make sense for your project? What are terms and adjectives that expand off of them? What theme might you create that could encompass all of these terms and thoughts? See the example below for what this might look like sketched out on a whiteboard:

With the above example, the word map begins with the term joy, and then expands in different directions. The team in the example goes in two primary directions—synonyms for joy and actions associated with joy. Then, you’ll see the connection built off of express and sharing towards community, two things that communities tend to do. The final result here might end up being a theme of “The Joys of Community,” based off the mapping and what meshes well.

Feelings and adjectives can also be associated with particular styles, so once you get into a concrete theme in this area like “The Joys of Community,” then you’d want to think about fonts and imagery that are associated with joy. This could be another place for the type of data collection and examples noted before where you create a makeshift dropbox for content that you can share to think through what the particular theme looks like when expressed horizontally across a campaign.

Creating a Final Theme Style Guide

Regardless of your direction, the goal of this phase is to come up with a concrete them that you can use for your deliverables and project. The end internal deliverable from all this work should be a concrete breakdown of what your theme will be and how that theme will impact your deliverables. The following items may be useful to build your theme into something that can be shared and used, the beginnings of a style guide (something we’ll get to in the next phase in more detail):

Theme description: What is your theme? How does it relate to your project’s goals and audience, and how does it impact the deliverables?

Theme colors and imagery: What colors and images are associated with this theme? Think categorically here.

Theme fonts: How does this theme translate into font choices? What fonts will be used, and where will they be used?

Theme layouts: What will be the various layouts/deliverable designs? How will they incorporate the theme to share information with your audience and to complete your goals?

Once you have all of this together, you’re in a good spot to start thinking about putting all of this into practice with a concrete style guide and some prototypes of your deliverables.