2.6: What the Hell Is RSS?

- Page ID

- 42993

What the Hell Is RSS?

I’ve heard that you can subscribe or something to RSS. Can you give me the lowdown, or do I need a PhD in Nerdology?

RSS stands for “Really Simple Syndication.” The somewhat silly word “syndication” refers to the distribution of radio and television content to stations who didn’t create the content but want to show it anyway. On the Web, content distribution is naturally easier—in fact, it’s “really simple.” All that is to say, when we’re talking about RSS, we’re talking about the delivery of content, or the question of how to get the Internet content you want brought straight to you, like your own personalized radio or TV channel.

But let’s back up and talk about how RSS actually works and what it can do for you. A great explanation of RSS is in the video RSS in Plain English, produced by the fun folks at Common Craft. They describe how in the traditional model of Web browsing, people surf from site to site to site, looking for new content that they’re interested in. That model is like shopping on a busy city street, where you sometimes find stuff you want, but you’re just as likely to find crappy fake watches and illegal DVDs of The Matrix as the stuff you’re actually trying to buy. RSS technology allows you to change your Web browsing to a model that’s more like online shopping, where you can stay home and have the things you want delivered instead of going out and browsing for them. With RSS, you can subscribe to the sites that you’re interested in and be notified in one central location (an “aggregator” or “feed reader”) when those sites have been updated. Instead of hopping from site to site in search of new content (“Anything new on this gaming site? Nope. Anything new on this music blog? Yeah!”), you can see all the updates in one spot.

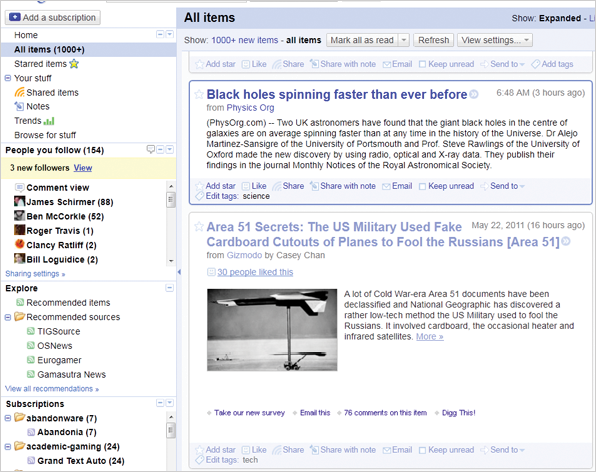

In action, it works like this: you go to the site of a feed reader like Google Reader (one of the most popular) and set up your account there (with your Google account). Then, whenever you are on a page that supports RSS and you want to subscribe, you look for an image of an orange box. (Depending on your browser, you may see that image in the address bar when you’re on a page that has RSS support.) When you click it, you will be given the option of subscribing to the feed in Google Reader (again, a process that may look slightly different on different sites and browsers). After you’ve subscribed, every time that site posts new content, you’ll be able to read it on Google Reader, without having to bounce around to all kinds of different sites. Google Reader also allows you to organize your subscriptions into folders (like “humor,” “anthropology,” or “cooking”), however you want.

We’ve talked about how RSS can benefit readers, but how about writers? It’s actually very, very important if you want to build an audience for your blog, wiki, or pretty much anything you do. If you don’t offer an RSS feed for people to subscribe to, you’re forcing them to have to actually visit your site to see your content—and fewer and fewer people are willing to do that. Simply put, if you don’t have an RSS feed, you’re already invisible to a big chunk of your potential readership.

Almost all wiki, blogging, and content management software already have RSS feeds built-in, and it’s usually “on” by default, so there’s nothing to worry about. Just make sure you see the orange square when you visit your site. If you don’t see it, check the options and help menus to figure out how to turn it on. If you’re coding your site from scratch, you’ll need to look into XML and learn how to properly tag your stuff. (Try the W3Schools RSS Tutorial.)

Most software will let you choose what you want in your RSS feed. Typically, you’ll have the option to just show the page title, the page title and a teaser, or the full posts. Usually, you’ll want the second option, since you want to tease the audience enough to have them actually visit your site. If you don’t care about that, go with the third option. The first option is the most restrictive and will probably reduce your visitors.

Once you know your RSS feed, you can promote it using Feedburner. Feedburner will let you track your subscribers and learn some things about them, such as where they’re from.

Figure 9. Google Reader is a full-featured RSS reader with tons of features.