3.5: Classical Rhetoric

- Page ID

- 173061

In James Murphy’s translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria, he explains that “Education for Quintilian begins in the cradle, and ends only when life itself ends.”[1] The result of a life of learning, for Quintilian, is a perfect speech where “the student is given a statement of a problem and asked to prepare an appropriate speech giving his solution.”[2] In this version of the world, a good citizen is always a PUBLIC participant. This forces the good citizen to know the rigors of public argumentation: “Rhetoric, or the theory of effective communication, is for Quintilian merely the tool of the broadly educated citizen who is capable of analysis, reflection, and powerful action in public affairs.”[3] For Quintilian, learning to argue in public is a lifelong affair. He believed that the “perfect orator. . . cannot exist unless he is above all a good man.”[4] Whether we agree with this or not, the hope for ethical behavior has been a part of public argumentation from the beginning.

The ancient model of rhetoric (or public argumentation) is complex. As a matter of fact, there is no single model of ancient argumentation. Plato claimed that the Sophists, such as Gorgias, were spin doctors weaving opinion and untruth for the delight of an audience and to the detriment of their moral fiber. For Plato, at least in the Phaedrus, public conversation was only useful if one applied it to the search for truth.[5] In the last decade, the work of the Sophists has been redeemed. Rather than spin doctors, Sophists like Isocrates, and even Gorgias to some degree, are viewed as arbiters of democracy because they believed that many people, not just male, property holding, Athenian citizens, could learn to use rhetoric effectively in public.

Aristotle gives us a slightly more systematic approach. He is very concerned with logic. For this reason, much of what is discussed below comes from his work. Aristotle explains that most men participate in public argument in some fashion. It is important to note that by “men,” Aristotle means citizens of Athens: adult males with the right to vote, not including women, foreigners, or slaves. Essentially this is a homogenous group by race, gender, and religious affiliation. We have to keep this in mind when adapting these strategies to our current heterogeneous culture. Aristotle explains,

for to a certain extent all men attempt to discuss statements and to maintain them, to defend themselves and to attack others. Ordinary people do this either at random or through practice and from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, the subject can plainly be handled systematically, for it is possible to inquire the reason why some speakers succeed through practice and others spontaneously; and every one will at once agree that such an inquiry is the function of an art.[6]

For Aristotle, inquiry into this field was artistic in nature. It required both skill and practice (some needed more of one than the other). Important here is the notion that public argument can be systematically learned.

Aristotle did not dwell on the ethics of an argument in Rhetoric (he leaves this to other texts). He argued that “things that are true and things that are just have a natural tendency to prevail over their opposites” and finally that “things that are true and things that are better are, by their nature, practically always easier to prove and easier to believe in.”[7] As a culture, we are skeptical of this kind of position, though often most believe it on a personal level. Aristotle admits in the next line that there are people who will use their skills at rhetoric for harm. As his job in this section is to defend the use of rhetoric itself, he claims that everything good can be used for harm, so rhetoric is no different from other fields. If this is true, there is even more need to educate the citizenry so that they will not be fooled by unethical and untruthful arguments.

For many, logic simply means reasoning. To understand a person’s logic, we try to find the structure of their reasoning. Logic is not synonymous with fact or truth, though facts are part of evidence in logical argumentation. You can be logical without being truthful. This is why more logic is not the only answer to better public argument.

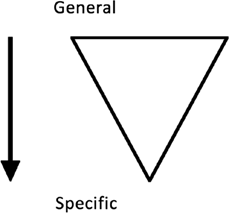

Our human brains are compelled to categorize the world as a survival mechanism. This survival mechanism allows for quicker thought. Two of the most basic logical strategies include inductive and deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning (see Figure 3.5.1)[8] starts from a premise that is a generalization about a large class of ideas, people, etc. and moves to a specific conclusion about a smaller category of ideas or things (All cats hate water; therefore, my neighbor’s cat will not jump in our pool). While the first premise is the most general, the second premise is a more particular observation. So the argument is created through common beliefs/observations that are compared to create an argument.

For example:

- Major Premise: People who burn flags are unpatriotic.

- Minor Premise: Sara burned a flag.

- Conclusion: Sara is unpatriotic.

The above line of logic is called a syllogism. As we can see in the example, the major premise offers a general belief held by some groups and the minor premise is a particular observation. The conclusion is drawn by comparing the premises and developing a conclusion. If you work hard enough, you can often take a complex argument and boil it down to a syllogism. This can reveal a great deal about the argument that is not apparent in the longer more complex version.

Stanley Fish, professor and New York Times columnist, offers the following syllogism in his July 22, 2007, blog entry titled “Democracy and Education”: “The syllogism underlying these comments is (1) America is a democracy (2) Schools and universities are situated within that democracy (3) Therefore schools and universities should be ordered and administrated according to democratic principles.”[9]

Fish offered the syllogism as a way to summarize the responses to his argument that students do not, in fact, have the right to free speech in a university classroom. The responses to Fish’s standpoint were vehemently opposed to his understanding of free speech rights and democracy. The responses are varied and complex. However, boiling them down to a single syllogism helps to summarize the primary rebuttal so that Fish could then offer his extended version of his standpoint.

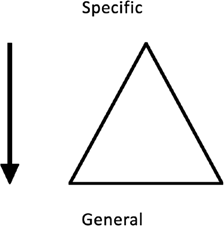

Inductive reasoning moves in a different direction than deductive reasoning (see Figure 3.5.2[10] below). Inductive reasoning starts with a particular or local statement and moves to a more general conclusion. We can think of inductive reasoning as a stacking of evidence. The more particular examples you give, the more it seems that your conclusion is correct.

Inductive reasoning is a common method for arguing, especially when the conclusion is an obvious probability. Inductive reasoning is the most common way that we move around in the world. If we experience something habitually, we reason that it will happen again. For example, if we walk down a city street and every person smiles, we might reason that this is a “nice town.” This seems logical. We have taken many similar, particular experiences (smiles) and used them to make a general conclusion (the people in the town are nice).

Most of the time, this reasoning works. However, we know that it can also lead us in the wrong direction. Perhaps the people were smiling because we were wearing inappropriate clothing (country togs in a metropolitan city), or perhaps only the people living on that particular street are “nice” and the rest of the town is unfriendly. Research papers sometimes rely too heavily on this logical method. Writers assume that finding ten versions of the same argument somehow proves that the point is true.

Most academic arguments in the humanities are inductive to some degree. When you study humanity, nothing is certain. When observing or making inductive arguments, it is important to get your evidence from many different areas, to judge it carefully, and acknowledge the flaws. Inductive arguments must be judged by the quality of the evidence since the conclusions are drawn directly from a body of compiled work.

The Appeals

“The appeals” offer a lesson in rhetoric that sticks with you long after the class has ended. Perhaps it is the rhythmic quality of the words (ethos, logos, pathos) or, simply, the usefulness of the concept. Aristotle imagined logos, ethos, and pathos as three kinds of artistic proof. Essentially, they highlight three ways to appeal to or persuade an audience: “(1) to reason logically, (2) to understand human character and goodness in its various forms, (3) to understand emotions.”[11]

While Aristotle and others did not explicitly dismiss emotional and character appeals, they found the most value in logic. Contemporary rhetoricians and argumentation scholars, however, recognize the power of emotions to sway us. Even the most stoic individuals have some emotional threshold over which no logic can pass. For example, we can seldom be reasonable when faced with a crime against a loved one, a betrayal, or the face of an adorable baby.

The easiest way to differentiate the appeals is to imagine selling a product based on them. Until recently, car commercials offered a prolific source of logical, ethical, and emotional appeals.

Logos

Using logic as proof for an argument. For many students this takes the form of numerical evidence. But as we have discussed above, logical reasoning is a kind of argumentation.

Car Commercial: (Syllogism) Americans love adventure—Ford Escape allows for off road adventure— Americans should buy a Ford Escape.

OR

The Ford Escape offers the best financial deal.

Ethos

Calling on particular shared values (patriotism), respected figures of authority (MLK), or one’s own character as a method for appealing to an audience.

Car Commercial: Eco-conscious Americans drive a Ford Escape.

OR

[Insert favorite movie star] drives a Ford Escape.

Pathos

Using emotionally driven images or language to sway your audience.

Car Commercial: Images of a pregnant woman being safely rushed to a hospital. Flash to two car seats in the back seat. Flash to family hopping out of their Ford Escape and witnessing the majesty of the Grand Canyon.

OR

After an image of a worried mother watching her sixteen year old daughter drive away: “Ford Escape takes the fear out of driving.”

The appeals are part of everyday conversation, even if we do not use the Greek terminology. Understanding the appeals helps us to make better rhetorical choices in designing our arguments. If you think about the appeals as a choice, their value is clear.[12]

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

This section contains material from:

Jones, Rebecca. “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?” In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, 156-179. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010. https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License.

- James Murphy, Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of Writing (Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1987), xxi. ↵

- Murphy, Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of Writing, xxiii. ↵

- Murphy, Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of Writing, xxvii. ↵

- Murphy, Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of Writing, 6. ↵

- Plato, “The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD],” Online Library of Liberty, n.d., accessed May 5, 2010. <http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=111&layout=html#chapter_39482>. ↵

- Lee Honeycutt, “Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Hypertextual Resource Compiled by Lee Honeycutt,” June 21, 2004, accessed May 5, 2010, 1354a I i. ↵

- Honeycutt, “Aristotle’s Rhetoric," 1355a I i. ↵

- “Deductive Reasoning” by Rebecca Jones is in: Rebecca Jones, “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?,” in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, eds. Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010), 156-179, https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. ↵

- Stanley Fish, “Democracy and Education,” New York Times, July 22, 2007, accessed May 5, 2010. ↵

- “Inductive Reasoning” by Rebecca Jones is in: Rebecca Jones, “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?,” in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, eds. Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010), 156-179, https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. ↵

- Lee Honeycutt, “Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Hypertextual Resource Compiled by Lee Honeycutt,” June 21, 2004, accessed May 5, 2010, 1356a. ↵

- This chapter originally contained the following citation in the Works Cited: Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students. 4th ed. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2009. Print. ↵