1.2.4: Model Texts by Student Authors

- Page ID

- 70804

Model Texts by Student Authors

Under the Knife38

The white fluorescent lights mirrored off the waxed and buffed vinyl flooring. Doctors and nurses beelined through small congregations of others conversing. Clocks were posted at every corner of every wall and the sum of the quiet ticking grew to an audible drone. From the vinyl floors to the desks where decade old Dell computers sat, a sickly gray sucked all the life from the room. The only source of color was the rainbow circle crocheted blanket that came customary for minors about to undergo surgery. It was supposed to be a token of warmth and happiness, a blanket you could find life in; however, all I found in the blanket was an unwanted pity.

Three months ago doctors diagnosed me with severe scoliosis. They told me I would need to pursue orthopedic surgery to realign my spine. For years I endured through back pain and discomfort, never attributing it to the disease. In part, I felt as if it was my fault, that me letting the symptoms go unattended for so long led it to become so extreme. Those months between the diagnosis and the surgery felt like mere seconds. Every day I would recite to myself that everything would be okay and that I had nothing to worry about. However, then minutes away from sedation, I felt like this bed I was in—only three feet off the ground—would put me six feet under.

The doctors informed me beforehand of the potential complications that could arise from surgery. Partial paralysis, infection, death, these words echoed throughout the chasms of my mind. Anxiety overwhelmed me; I was a dying animal surrounded by ravenous vultures, drool dripping awaiting their next meal. My palms were a disgusting swamp of sweat that gripped hard onto the white sheets that covered me. A feeling of numbness lurked into my extremities and slowly infected its way throughout my body

The vinyl mattress cover I was on felt like a porcelain toilet seat during a cold winter morning. It did not help my discomfort that I had nothing on but a sea blue gown that covered only the front and ankle high socks that seemed like bathroom scrubbers. A heart rate monitor clamp was tightly affixed onto my index finger that had already lost circulation minutes ago. The monitor was the snitch giving away my growing anxiety; my heart rate began to increase as I awaited surgery. Attached to the bed frame was a remote that could adjust almost every aspect of the bed. I kept the bed at an almost right angle: I wanted to be aware of my surroundings.

My orthopediatrician and surgeon, Dr. Halsey, paced in from the hallway and gave away a forced smile to ease me into comfort. The doctor shot out his hand and I hesitantly stuck out mine for the handshake. I’ve always hated handshakes; my hands are incredibly sweaty and I did not want to disgust him with my soggy tofu hands. He asked me how my day was so far, and I responded with a concise “Alright.” Truth was, my day so far was pretty lackluster and tiring. I had woken up before the birds had even begun to chirp, I ate nothing for breakfast, and I was terrified out of my mind. This Orthopedic Surgeon, this man, this human, was fully in charge of the surgery. Dr. Halsey and other surgeons deal with one of the most delicate and fragile things in the world—people’s lives. The amount of pressure and nerves he must face on an everyday basis is incredible. His calm and reserved nature made me believe that he was confident in himself, and that put me more at ease.

An overweight nurse wheeled in an IV with a bag of solution hooked to the side. “Which arm do you prefer for your IV?” she inquired.

Needles used to terrify me. They were tiny bullets that pierced through your skin like mosquitos looking for dinner, but by now I had grown accustomed to them. Like getting stung by a bee for the first time, my first time getting blood taken was a grueling adventure. “Left, I guess,” I let out with a long anxiety-filled sigh.

The rubber band was thick and dark blue, the same color as the latex gloves she wore. I could feel my arm pulse in excitement as they tightly wrapped the rubber band right above my elbow.

“Oh, wow! Look at that vein pop right out!” The nurse exclaimed as she inspected the bulging vein.

I tried to distract myself from the nurse so I wouldn’t hesitate as the IV was going in. I stared intently at the speckled ceiling tiles. They were the same ones used in schools. As my eyes began to relax, the dots on the ceiling started to transform into different shapes and animals. There was a squirrel, a seal, and a do—I felt pain shock through my body as the IV needle had infiltrated into my arm.

Dr. Halsey had one arm planted to the bottom end of the bed frame and the other holding the clipboard that was attached to the frame. “We’re going to pump two solutions through you. The first will be the saline, and the second will be the sedation and anesthesia.” The nurse leaned over and punched in buttons connected to the IV. After a loud beep, I felt a cooling sensation run down my arm. I felt like a criminal, prosecuted for murder, and now was one chemical away from finishing the cocktail execution. My eyes darted across the room; I was searching for hope I could cling to.

My mother was sitting on a chair on the other side of the room, eyes slowly and silently sweating. She clutched my father’s giant calloused hands as he browsed the internet on his phone. While I would say that I am more similar to my mother than my father, I think we both dealt with our anxiety in similar ways. Just like my father, I too needed a visual distraction to avoid my anxiety. “I love you,” my mother called out.

All I did was a slight nod in affirmation. I was too fully engulfed by my own thoughts to even try and let out a single syllable. What is my purpose in life? Have I been successful in making others proud? Questions like these crept up in my mind like an unwanted visitor.

“Here comes the next solution,” Dr. Halsey announced while pointing his pen at the IV bags. “10…,” he began his countdown.

I needed answers to the questions that had invaded my mind. So far in life, I haven’t done anything praiseworthy or even noteworthy. I am the bottom of the barrel, a dime a dozen, someone who will probably never influence the future to come. However, in those final seconds, I realized that I did not really care.

“7...,” Dr. Halsey continued the countdown.

I’ve enjoyed my life. I’ve had my fun and shared many experiences with my closest friends. If I’m not remembered in a few years after I die, then so be it. I’m proud of my small accomplishments so far.

“4…” Although I am not the most decorated of students, I can say that at least I tried my hardest. All that really mattered was that I was happy. I had hit tranquility; my mind had halted. I was out even before Dr. Halsey finished the countdown. I was at ease.

Breathing Easy39

Most people’s midlife crises happen when they’re well into adulthood; mine happened when I was twelve. For most of my childhood and into my early teen years, I was actively involved in community theater. In the fall of 2010, I was in the throes of puberty as well as in the middle of rehearsals for a production of Pinocchio, in which I played the glamorous and highly coveted role of an unnamed puppet. On this particular day, however, I was not onstage rehearsing with all the other unnamed puppets as I should’ve been; instead, I was locked backstage in a single-stall bathroom, dressed in my harlequin costume and crying my eyes out on the freezing tile floor, the gaudy red and black makeup dripping down my face until I looked like the villain from a low-budget horror movie.

The timing of this breakdown was not ideal. I don’t remember exactly what happened in the middle of rehearsal that triggered this moment of hysteria, but I know it had been building for a long time, and for whatever reason, that was the day the dam finally broke. At the time, I had pinpointed the start of my crisis to a moment several months earlier when I started questioning my sexuality. Looking back now, though, I can see that this aspect of my identity had been there since childhood, when as a seven-year-old I couldn’t decide if I would rather marry Aladdin or Princess Jasmine.

Up until the age of 16, I lived in Amarillo, Texas, a flat, brown city in the middle of a huge red state. Even though my parents had never been blatantly homophobic in front of me, I grew up in a conservative religious community that was fiercely cisheteronormative. My eighth-grade health teacher kicked off our unit on sex education with a contemptuous, “We aren’t going to bother learning about safe sex for homosexuals. We’re only going to talk about normal relationships.” Another time, when I told a friend about a secret I had (unrelated to my sexuality), she responded with, “That’s not too bad. At least you’re not gay,” her lips curling in disdain as if simply saying the sinful word aloud left a bad taste in her mouth.

I laid in a crumpled mess on that bathroom floor, crying until my head throbbed and the linoleum beneath me became slick with tears and dollar-store face paint. By the time my crying slowed and I finally pulled myself up off the floor, my entire body felt weighed down by the secret I now knew I had to keep, and despite being a perfectionist at heart, I couldn’t find it within myself to care that I’d missed almost all of rehearsal. I looked at my tear-streaked face in the mirror, makeup smeared all over my burning cheeks, and silently admitted to myself what I had subconsciously known for a long time: that I wasn’t straight, even though I didn’t know exactly what I was yet. At the time, even thinking the words “I might be gay” to myself felt like a death sentence. I promised myself then and there that I would never tell anyone; that seemed to be the only option.

For several years, I managed to keep my promise to myself. Whereas before I had spent almost all of my free time with my friends, after my episode in the bathroom, I became isolated, making up excuses anytime a friend invited me out for fear of accidentally getting too comfortable and letting my secret slip. I spent most of middle school and the beginning of high school so far back in the closet I could barely breathe or see any light. I felt like the puppet I’d played in that production of Pinocchio—tied down by fear and shame, controlled by other people and their expectations of me rather than having the ability to be honest about who I was.

Just as I ended up breaking down in that theater bathroom stall when I was twelve, though, I eventually broke down again. My freshman year of high school was one of the worst years of my life. Struggling with mental illness and missing large portions of school as I went in and out of psychiatric hospitals was hard enough, but on top of all of that, I was also lying about a core part of my identity to everyone I knew. After a particularly rough night, I sat down and wrote a letter to my parents explaining that I was pansexual (or attracted to all genders and gender identities). “I’ve tried to stop being this way, but I can’t,” I wrote, my normally-neat handwriting reduced to a shaky chicken scratch as I struggled to control the trembling of my hands. “I hope you still love me.” With my heart pounding violently in my chest, I signed the letter and left it in the kitchen for them to find before locking myself in my room and pretending to go to sleep so I wouldn’t have to deal with their initial response.

By some amazing twist of fate, my parents did not have the horrible reaction I’d been dreading for the past two years. They knocked on my door a few minutes after I’d left the letter for them, and when I nervously let them in, they hugged me and told me that they loved me no matter what; my dad even said, “Kid, you couldn’t have picked a better family to be gay in.” For the first time in years, I felt like I could breathe again. My fear of rejection was still there—after all, I still had to come out to most of my friends and extended family—but it seemed so much more manageable knowing I had my parents on my side.

It took me several years to fully come out and get to a point where I felt comfortable in my own identity. A lot of people, even those who had known and loved me since I was a baby, told me that they couldn’t be friends with me or my family anymore because of my “sinful lifestyle.” As painful as it was each time I was shunned by someone I thought was my friend, I eventually gained enough confidence in myself and my identity to stop caring as much when people tried to tear me down for something I know is outside of my control.

Now, as a fully out-of-the-closet queer person, I still face discrimination from certain people in my life and from society as a whole. However, I’ve learned that it’s a lot easier to deal with judgement from external forces when you surround yourself with people who love and support you, and most importantly, when you have love for yourself, which I’m glad to say I now do. Even though it was terrifying at first, I’m glad I broke the promise I made to myself in that backstage bathroom, because no matter what struggles I might face, at least I know I’m able to be open about who I am.

Before I got sober I never paid attention to my dreams. I don’t even remember if I had dreams. In the end I was spiritually broken, hopeless, scared and desperate. My life was dedicated to blotting out my miserable existence using copious amounts of booze and drugs. The substances stopped working. Every night was intoxicated tear soaked erratic fits of despair until I passed out. Only to wake up the next morning and begin the vicious cycle all over. Bending and writhing my way out of a five year heroin and alcohol addiction was just as scary. I was in jail. I had no idea how to live. I had no purpose in life. Then the dreams came back. Some of them were terrifying. Some dreams had inspiration. There is one dream I will never forget.

I am standing in a room full of people. They are all sitting looking up at me. I am holding a hand drum. My hands are shaking and I am extremely nervous. An old woman enters the room and walks up to me. The old woman is about half my height. She is barefoot and wearing a long green wool dress. She is holding a walking stick and is draped in animal furs. She has long flowing hair that falls over the animal furs. The old woman looks at all the people in the room. Then she looks at me and says, “It’s okay, they are waiting, sing.” My heart is racing. I strike the hand drum with all my courage. I feel the heartbeat of the drum. It’s my heartbeat. I begin to sing, honoring the four directions. After each verse I pause and the old woman pushes me forward “It’s okay,” she says, “Sing.” I am singing louder now. The third verse is powerful. I am striking the drum with all my strength. Many people singing with me. My spirit is strong. During the fourth verse sparks are flying from the contact between the beater stick and my drum. I am striking the drum with all our strength. We are all singing together. The room is shaking with spirit. The old woman looks over at me and smiles.

I woke up. My heart was racing. I took a deep breath of recirculated air. I could taste the institution. I looked over and saw my cellmate sleeping. I remembered where I was. I knew what I had to do. I had to get sober and stay sober. I had to find my spirit. I had to sing.

At six months of sobriety I was out in the real world. I was living on the Oregon Coast and I was attending local AA meetings. I was still lost but had the dream about singing with the drum in the back of my mind. One day an oldtimer walked into the meeting and sat down. He introduced himself, “My name is Gary, and I am an alcoholic from Colorado.” We all respond, “Welcome Gary.” Gary intrigued me. He was wearing old jeans, a sweatshirt and a faded old native pride hat with an eagle feather embroider on the front. Beneath the hat he wore round eyeglasses which sat on top of his large nose, below his nose was a bushy mustache. He resembled an Indian version of Groucho Marx. Something felt familiar about his spirit. After the meeting Gary walked up and introduced himself to me. I invited him to our native recovery circle we have on Wednesday nights.

Gary came to our circle that Wednesday. We made plans to hang out after the meeting. Gary is Oglala Lakota. He is a pipe carrier for the people. We decide to hold a pipe ceremony in order to establish connectedness and unite with one heart and mind. To pray and get to know each other. We went down to the beach and lit a fire. It was a clear, warm night. The stars were bright. The fire was crackling and the shadows of the flames were bouncing of the clear night sky. I took my shoes off and felt the cool soft sand beneath my feet and between my toes. The ocean was rumbling in the distance. Gary started digging around in his bag. The firelight bounced off his glasses giving a twinkle in his eye as he gave me a little smile. He pulled out a hand drum. My heart stopped. He began to sing a song. I knew that song. He was honoring the four directions. My eyes began to water and a wave of emotion flooded over me. I looked up to the stars with gratitude. I asked Gary if he would teach me and he shrugged.

I began to hang around Gary a lot. I would just listen. He let me practice with his drum. He would talk and I would listen. Sometimes he would sing and I would sing along. We continued to go to our native recovery circle. It was growing in attendance. Gary would open the meeting by honoring the four directions with the song and we would smudge down. I would listen and sometimes sing along.

I had a year of sobriety when I got my first drum making supplies. I called Gary and he came over to help me make it. Gary showed me how to prep the hide. How to stretch the hide over the wooden hoop and how to lace it up in the back. I began to find purpose in the simple act of learning how to create stuff. I brought my drum to our native recovery circle. Around forty people attend our circle now. Many of them young and new still struggling with addiction. We lit the sage to open the meeting. The smoke began to rise into the sky. I inhaled the smoky scent deep and could feel the serenity and cleansing property of the sage medicine. I looked around at all the people. They were all looking at me and waiting. Then I looked at Gary. Gary smiled and said, “It’s okay, they are all waiting, sing.”

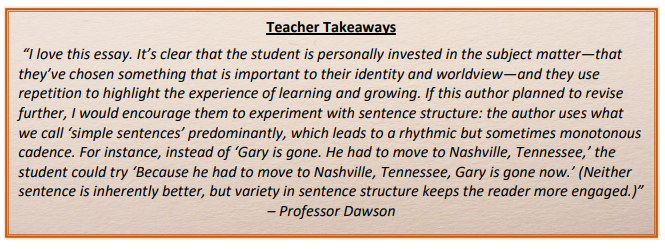

We now have another recovery circle here in Portland on Friday nights. Gary is gone. He had to move to Nashville, Tennessee. Many people come to our circle to find healing from drug and alcohol abuse. We light the sage and smudge down while I honor the four directions with the same song. I carry many of the traditional prayer songs today. Most of them given to me by Gary.

At one meeting a young man struggling with alcoholism approaches me and tells me he needs to sing and wants to learn the songs. The next week we open the meeting and light the sage. The young man is standing next to me holding his own drum. His own heartbeat. He looks at all the people. They are all looking at him. He looks at me. I smile and say, “It’s okay, they are waiting, sing.”