1.2.2: Techniques

- Page ID

- 70802

Techniques

Plot Shapes and Form

Plot is one of the basic elements of every story: put simply, plot refers to the actual events that take place within the bounds of your narrative. Using our rhetorical situation vocabulary, we can identify “plot” as the primary subject of a descriptive personal narrative. Three related elements to consider are scope, sequence, and pacing.

Scope

The term scope refers to the boundaries of your plot. Where and when does it begin and end? What is its focus? What background information and details does your story require? I often think about narrative scope as the edges of a photograph: a photo, whether of a vast landscape or a microscopic organism, has boundaries. Those boundaries inform the viewer’s perception. In this example, the scope of the left photo allows for a story about a neighborhood in San Francisco. In the middle, it is a story about the fire escape, the clouds. On the right, the scope of the story directs our attention to the birds. In this way, narrative scope impacts the content you include and your reader’s perception of that content in context.

"SF Neighborhood" by SBT4NOW is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The way we determine scope varies based on rhetorical situation, but I can say generally that many developing writers struggle with a scope that is too broad: writers often find it challenging to zero in on the events that drive a story and prune out extraneous information.

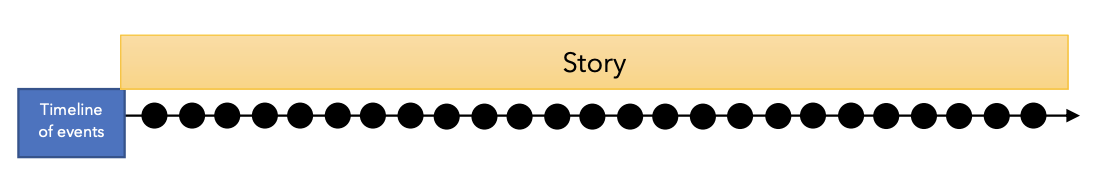

Consider, as an example, how you might respond if your friend asked what you did last weekend. If you began with, “I woke up on Saturday morning, rolled over, checked my phone, fell back asleep, woke up, pulled my feet out from under the covers, put my feet on the floor, stood up, stretched…” then your friend might have stopped listening by the time you get to the really good stuff. Your scope is too broad, so you’re including details that distract or bore your reader. Instead of listing every detail in order like this:

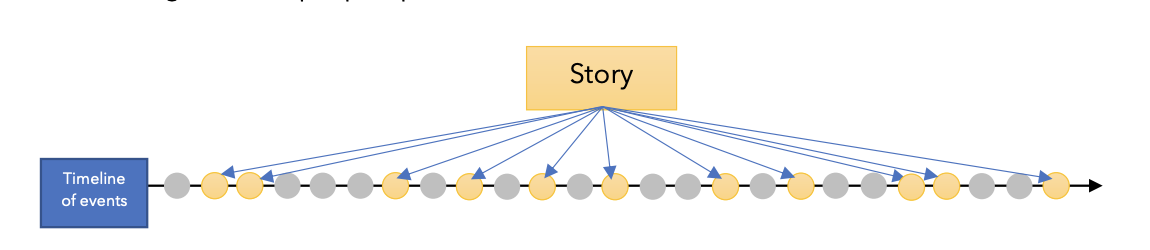

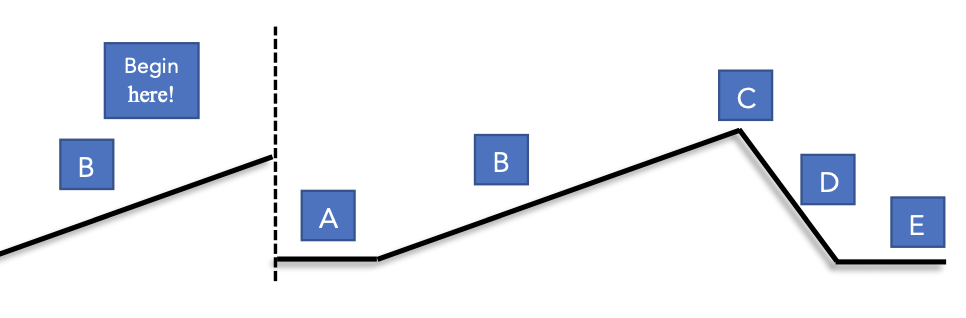

… you should consider narrowing your scope, focusing instead on the important, interesting, and unique plot points (events) like this:

You might think of this as the difference between a series of snapshots and a roll of film: instead of twenty-four frames per second video, your entire story might only be a few photographs aligned together.

The most impactful stories are often those that represent something, so your scope should focus on the details that fit into the bigger picture. To return to the previous example, you could tell me more about your weekend by sharing a specific detail than every detail. “Brushing my teeth Saturday morning, I didn’t realize that I would probably have a scar from wrestling that bear on Sunday” reveals more than “I woke up on Saturday morning, rolled over, checked my phone, fell back asleep, woke up, pulled my feet out from under the covers, put my feet on the floor, stood up, stretched….” Not only have you foregrounded the more interesting event, but you have also foreshadowed that you had a harrowing, adventurous, and unexpected weekend.

Sequence and Pacing

The sequence and pacing of your plot—the order of the events and the amount of time you give to each event, respectively—will determine your reader’s experience. There are an infinite number of ways you might structure your story, and the shape of your story is worth deep consideration. Although the traditional forms for narrative sequence are not your only options, let’s take a look at a few tried-and-true shapes your plot might take.

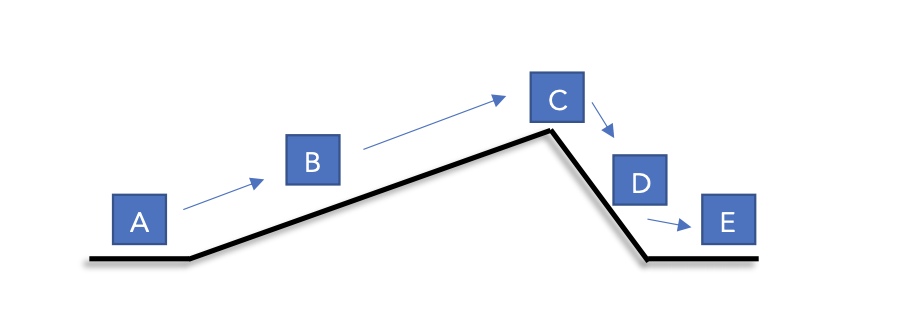

You might recognize Freytag’s Pyramid29 from other classes you’ve taken:

A. Exposition: Here, you’re setting the scene, introducing characters, and preparing the reader for the journey.

B. Rising action: In this part, things start to happen. You (or your characters) encounter conflict, set out on a journey, meet people, etc.

C. Climax: This is the peak of the action, the main showdown, the central event toward which your story has been building.

D. Falling action: Now things start to wind down. You (or your characters) come away from the climactic experience changed—at the very least, you are wiser for having had that experience.

E. Resolution: Also known as dénouement, this is where all the loose ends get tied up. The central conflict has been resolved, and everything is back to normal, but perhaps a bit different.

This narrative shape is certainly a familiar one. Many films, TV shows, plays, novels, and short stories follow this track. But it’s not without its flaws. You should discuss with your classmates and instructors what shortcomings you see in this classic plot shape. What assumptions does it rely on? How might it limit a storyteller? Sometimes, I tell my students to “Start the story where the story starts”—often, steps A and B in the diagram above just delay the most descriptive, active, or meaningful parts of the story. If nothing else, we should note that it is not necessarily the best way to tell your story, and definitely not the only way.

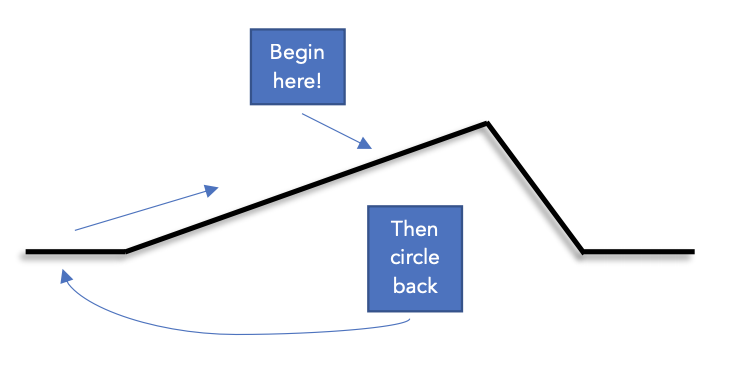

Another classic technique for narrative sequence is known as in medias res—literally, “in the middle of things.” As you map out your plot in pre-writing or experiment with during the drafting and revision process, you might find this technique a more active and exciting way to begin a story.

In the earlier example, the plot is chronological, linear, and continuous: the story would move smoothly from beginning to end with no interruptions. In medias res instead suggests that you start your story with action rather than exposition, focusing on an exciting, imagistic, or important scene. Then, you can circle back to an earlier part of the story to fill in the blanks for your reader. Using the previously discussed plot shape, you might visualize it like this:

or...

You can experiment with your sequence in a variety of other ways, which might include also making changes to your scope: instead of a continuous story, you might have a series of fragments with specific scope (like photographs instead of video), as is exemplified by “The Pot Calling the Kettle Black….” Instead of chronological order, you might bounce around in time or space, like in “Parental Guidance,” or in reverse, like “21.” Some of my favorite narratives reject traditional narrative sequence.

I include pacing with sequence because a change to one often influences the other. Put simply, pacing refers to the speed and fluidity with which a reader moves through your story. You can play with pacing by moving more quickly through events, or even by experimenting with sentence and paragraph length. Consider how the “flow” of the following examples differs:

A. The train screeched to a halt. A flock of pigeons took flight as the conductor announced, “We’ll be stuck here for a few minutes.”

B. Lost in my thoughts, I shuddered as the train ground to a full stop in the middle of an intersection. I was surprised, jarred by the unannounced and abrupt jerking of the car. I sought clues for our stop outside the window. All I saw were pigeons as startled and clueless as I.

I recommend the student essay “Under the Knife,” which does excellent work with pacing, in addition to making a strong creative choice with narrative scope.

The position from which your story is told will help shape your reader’s experience, the language your narrator and characters use, and even the plot itself. You might recognize this from Dear White People Volume 1 or Arrested Development Season 4, both Netflix TV series. Typically, each episode in these seasons explores similar plot events, but from a different character’s perspective. Because of their unique vantage points, characters can tell different stories about the same realities.

"Different perspective" by Carlos ZGZ is in the Public Domain, CC0

This is, of course, true for our lives more generally. In addition to our differences in knowledge and experiences, we also interpret and understand events differently. In our writing, narrative position is informed by point-of-view and the emotional valences I refer to here as tone and mood.

point-of-view (POV): the perspective from which a story is told.

- This is a grammatical phenomenon—i.e., it decides pronoun use—but, more importantly, it impacts tone, mood, scope, voice, and plot.30

Although point-of-view will influence tone and mood, we can also consider what feelings we want to convey and inspire independently as part of our narrative position.

tone: the emotional register of the story’s language.

- What emotional state does the narrator of the story (not the author, but the speaker) seem to be in? What emotions are you trying to imbue in your writing?

mood: the emotional register a reader experiences.31

- What emotions do you want your reader to experience? Are they the same feelings you experienced at the time?

| Examples: | |||

|

1st person |

Narrator uses 1st person pronouns (I/me/mine or us/we/ours) | Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of the narrator. Limited certainty of motives, thoughts, or feelings of other characters | I tripped on the last stair, preoccupied by what my sister had said, and felt my stomach drop. |

| 2nd person | Narrator uses 2nd person pronouns (you/your) | Speaks to the reader, as if the reader is the protagonist OR uses apostrophe to speak to an absent or unidentified person |

Your breath catches as you feel the phantom step. O, staircase, how you keep me awake at night. |

| 3rd person limited | Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/ theirs) | Sometimes called “close” third person. Observes and narrates but sticks near one or two characters, in contrast with 3rd person omniscient. | He was visibly frustrated by his sister’s nonchalance and wasn’t watching his step. |

| 3rd person omniscient |

Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/ theirs) |

Observes and narrates from an all-knowing perspective. Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of all characters. | Beneath the surface, his sister felt regretful. Why did I tell him that? she wondered. |

| stream-of-consciousness | Narrator uses inconsistent pronouns, or no pronouns at all | Approximates the digressive, wandering, and ungrammatical thought processes of the narrator. | But now, a thousand empty⎯where?⎯and she, with head shake, will be fine⎯AHH! |

Typically, you will tell your story from the first-person point-of-view, but personal narratives can also be told from a different perspective; I recommend “Comatose Dreams” to illustrate this at work. As you’re developing and revising your writing, try to inhabit different authorial positions: What would change if you used the third person POV instead of first person? What different meanings would your reader find if you told this story with a different tone—bitter instead of nostalgic, proud rather than embarrassed, sarcastic rather than genuine?

Furthermore, there are many rhetorical situations that call for different POVs. (For instance, you may have noticed that this book uses the second-person very frequently.) So, as you evaluate which POV will be most effective for your current rhetorical situation, bear in mind that the same choice might inform your future writing.

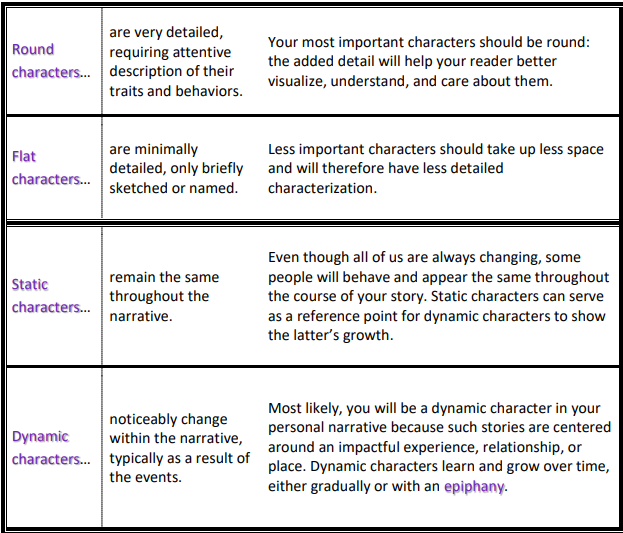

Whether your story is fiction or nonfiction, you should spend some time thinking about characterization: the development of characters through actions, descriptions, and dialogue. Your audience will be more engaged with and sympathetic toward your narrative if they can vividly imagine the characters as real people.

Like description, characterization relies on specificity. Consider the following contrast in character descriptions:

A. My mom is great. She is an average-sized brunette with brown eyes. She is very loving and supportive, and I know I can rely on her. She taught me everything I know.

B. In addition to some of my father’s idiosyncrasies, however, he is also one of the most kind-hearted and loving people in my life. One of his signature actions is the ‘cry-smile,’ in which he simultaneously cries and smiles any time he experiences a strong positive emotion (which is almost daily).32

How does the “cry-smile” detail enhance the characterization of the speaker’s parent?

To break it down to process, characterization can be accomplished in two ways:

a) Directly, through specific description of the character—What kind of clothes do they wear? What do they look, smell, sound like?—or,

b) Indirectly, through the behaviors, speech, and thoughts of the character— What kind of language, dialect, or register do they use? What is the tone, inflection, and timbre of their voice? How does their manner of speaking reflect their attitude toward the listener? How do their actions reflect their traits? What’s on their mind that they won’t share with the world?

Thinking through these questions will help you get a better understanding of each character (often including yourself!). You do not need to include all the details, but they should inform your description, dialogue, and narration.

Dialogue33

dialogue: communication between two or more characters.

"Conversation" by Ray Wewerka is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Think of the different conversations you’ve had today, with family, friends, or even classmates. Within each of those conversations, there were likely pre-established relationships that determined how you talked to each other: each is its own rhetorical situation. A dialogue with your friends, for example, may be far different from one with your family. These relationships can influence tone of voice, word choice (such as using slang, jargon, or lingo), what details we share, and even what language we speak.

As we’ve seen above, good dialogue often demonstrates the traits of a character or the relationship of characters. From reading or listening to how people talk to one another, we often infer the relationships they have. We can tell if they’re having an argument or conflict, if one is experiencing some internal conflict or trauma, if they’re friendly acquaintances or cold strangers, even how their emotional or professional attributes align or create opposition.

Often, dialogue does more than just one thing, which makes it a challenging tool to master. When dialogue isn’t doing more than one thing, it can feel flat or expositional, like a bad movie or TV show where everyone is saying their feelings or explaining what just happened. For example, there is a difference between “No thanks, I’m not hungry” and “I’ve told you, I’m not hungry.” The latter shows frustration, and hints at a previous conversation. Exposition can have a place in dialogue, but we should use it deliberately, with an awareness of how natural or unnatural it may sound. We should be aware how dialogue impacts the pacing of the narrative. Dialogue can be musical and create tempo, with either quick back and forth, or long drawn out pauses between two characters. Rhythm of a dialogue can also tell us about the characters’ relationship and emotions.

We can put some of these thoughts to the test using the exercises in the Activities section of this chapter to practice writing dialogue.

Narration, as you already know, can occur in a variety of media: TV shows, music, drama, and even Snapchat Stories practice narration in different ways. Your instructor may ask you to write a traditional personal narrative (using only prose), but if you are given the opportunity, you might also consider what other media or genres might inform your narration. Some awesome narratives use a multimedia or multigenre approach, synthesizing multiple different forms, like audio and video, or nonfiction, poetry, and photography.

In addition to the limitations and opportunities presented by your rhetorical situation, choosing a medium also depends on the opportunities and limitations of different forms. To determine which tool or tools you want to use for your story, you should consider which medium (or combination of media) will help you best accomplish your purpose. Here’s a non-comprehensive list of storytelling tools you might incorporate in place of or in addition to traditional prose:

- Images

- Poetry

- Video

- Audio recording

- “Found” texts (fragments of other authors’ works reframed to tell a different story)

- Illustrations

- Comics, manga, or other graphic storytelling

- Journal entries or series of letters

- Plays, screenplays, or other works of drama

- Blogs and social media postings

Although each of these media is a vehicle for delivering information, it is important to acknowledge that each different medium will have a different impact on the audience; in other words, the medium can change the message itself.

There are a number of digital tools available that you might consider for your storytelling medium, as well.34

Video: Storytelling with Robyn Vazquez35

Video of Storytelling with Robyn Vazquez is available via PSU Media Space.