14.4: Writing Process- Informing and Analyzing

- Page ID

- 140574

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Successfully apply citation conventions to your writing, understanding the ideas of intellectual property that motivate their use.

- Evaluate research materials for credibility, sufficiency, accuracy, timeliness, and bias.

- Compose to discover and reconsider ideas.

- Compose an annotated bibliography that uses correct style conventions and integrates the writer’s ideas with ideas from related sources.

Now it is time to try your hand at creating your own annotated bibliography. As you work through identifying and writing about your sources, you may want to seek out additional ones to help support your argument or thesis. This recursive process is similar to the fine-tuning that occurs during the writing process, in which a writer moves fluidly among drafting, editing, and revising. You can return to your annotated bibliography during the course of research and writing to modify, further develop, analyze, and add to your sources. Remember, using a variety of sources can broaden your perspective about your topic by showing how different scholars and popular publications approach it.

Summary of Assingment: Annotated Bibliography

For this assignment, you will create an annotated bibliography based on your research for one of the writing assignments in this course, preferably Writing Process: Integrating Research. After collecting and choosing sources, you will write citations using MLA Documentation and Format and compose a one- or two-paragraph annotation for each source. Remember, the purpose of the annotation is to provide

- a brief summary that allows readers to understand the background of the source and its basic claims; and

- an evaluation and reflection on the source’s reliability, its usefulness, and the author’s or organization’s credibility.

While the format for your MLA citation should follow the prescriptive pattern from the Handbook, you will decide on the language and structure of the annotations you include. While your topic, personal style, and ideas may lend themselves to a more standardized format, it is possible that they may instead challenge codified conventions in favor of a style more authentic to you.

Another Lens 1. Consider alternatives to a formal annotated bibliography that complements differing learning styles or abilities. If your instructor is amenable, you may informally annotate sources in their margins or use an online annotation program such as Kami (https://openstax.org/r/Kami).

Another Lens 2. Another alternative is to discuss, with a partner or in a small group, each source’s credentials, key ideas, and usefulness to your project. In either case, using a graphic organizer similar to the one in the next section should help you organize your ideas.

Quick Launch: Organizing Information

Begin by collecting sources. A good way to start is to make a list of keywords, known authors, organizations, and previously identified sources related to your topic. For example, imagine you have been assigned an argument project and chosen artificial intelligence as the topic. Begin, then, with the keywords artificial intelligence. A Google search will reveal a wealth of information on the topic, likely too much to help you craft a meaningful argument. However, a basic search will allow you to

- effectively define artificial intelligence as “the simulation of human intelligence by machines programmed to mimic human thought and actions”;

- name four types of artificial intelligence: reactive machines, limited memory, theory of mind, and self-aware;

- identify leading industries in which artificial intelligence is already present, such as self-driving cars and virtual butlers; and

- recognize the existence of a spectrum of thought surrounding the ethics and governance of artificial intelligence.

You also may discover some alternative search terms to use, such as machine learning, data mining, robotics, and neuroscience. Although you may not ultimately use them in your argument, the sources that you find may point you toward a focused thesis.

When you finish your keyword search, the next step is to search academic databases. Use your library’s resources to find scholarly sources such as journal articles, books, textbooks, expert interviews, and reputable periodical pieces. Aim for five to seven sources to begin with, though you likely will add more as you work on your project. You may already have an idea of what claims you want to make in your argument, but the sources may shape them as well. As you review the sources you collect, choose those that give you a varied range of perspectives on the topic. Remember that you can return to this procedure at various points in your research, adding sources as your needs change and as you refine your claims. While you search for sources, keep in mind the specifics of your research project, and limit your search to sources that specifically support your argument, inform a counterargument, or otherwise add information that enhances your research.

Thesis

Before you choose sources, you must have an idea of what you want to say. If you’re creating an annotated bibliography for the argument described Writing Process: Integrating Research, you likely have already drafted a thesis statement. If you are creating an annotated bibliography for another topic, you will need to draft a working thesis. Your thesis will state your position on the topic. It is often a single clear, concise sentence that reveals your side in the argument. You will use your sources to support the thesis you draft.

These frames may be useful when you draft your working thesis:

- Because ________, [someone] should ________.

- ________ saves ________, reduces ________, and helps ________.

- The lack of ________ shows ________.

- ________ influences ________ and, by extension, ________.

- ________ accurately (inaccurately) portrays ________ because ________.

- ________ is a result of ________, ________, and ________.

- Although some argue that ________, a close examination shows that ________.

- ________ and ________ prove that ________.

Citations and Annotations

For each source you choose, first write the source citation in MLA format. An example of a citation for the research project on artificial intelligence might be:

Buiten, Miriam C. “Towards Intelligent Regulation of Artificial Intelligence.” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–59, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regulation/article/towards-intelligent-regulation-of-artificial-intelligence/ AF1AD1940B70DB88D2B24202EE933F1B. Accessed 23 Jan. 2021.

After preparing citations for each of your sources, write the annotations. To do this, consider the following: • The purpose of the work

- For whom the work is written

- How to summarize the content

- The author/organization producing the work

- Distinctive or interesting features of the content (particularly in comparison with other sources)

- The relevance of the work to your topic

- Strengths, weaknesses, and bias present

- Conclusions and implications

To annotate, you will typically begin with a summary of one to three sentences. For longer or more complex sources, the summary may be longer. Then discuss unique features of the content, an evaluation of the source, and a reflection on how the source is useful to your research. For each source, use a graphic organizer such as Table \(14.3\). It will help you collect the needed information, organize your thoughts, and get started summarizing and analyzing your sources.

| Source Citation | |

| Intended Audience | |

| Main Ideas, Arguments, and Themes Present | |

| Author's Point of View, Bias, and Expertise | |

| Comparison with Other Sources on the Topic | |

| Evaluation of Source's Relevance to Topic | |

| Evaluation of Strengths and Weaknesses | |

| Conclusions Drawn by Author |

Drafting:

Creating an annotated bibliography requires you to read your sources critically. As you first collect your sources, briefly review and examine the information they contain, specifically through the lens of how each can add to your research. As you read more critically, choose those that represent different perspectives on your topic as well as those that have similar viewpoints but arrive at them in different ways or from various angles.

If you have been using a graphic organizer for each source, as suggested, the information you need and your ideas about the source will be right there for you. If you haven’t organized your research in this way, now is a good time to do it, when you do not yet need to structure good paragraphs. When it is time for you to write your annotations, having your thoughts already mapped out will make your work easier. For the hypothetical artificial intelligence project, you might organize information for the article cited earlier as shown in Table \(14.4\).

| Source Citation | Buiten, Miriam C. “Towards Intelligent Regulation of Artificial Intelligence.” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–59, www.cambridge.org/ core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regulation/article/towards-intelligent-regulation-of-artificial-intelligence/AF1AD1940B70DB88D2B24202EE933F1B. Accessed 23 Jan. 2021. |

| Intendend Audience | The journal is published by Cambridge University Press. Therefore, it is peer reviewed and intended for an academic audience. |

| Main Ideas, Arguments, and Themes Present | Discusses the unpredictability and difficulty of controlling artificial intelligence and examines what, if anything, can be done to increase transparency, specifically as it relates to biases of algorithms |

| Author's Point of View, Bias, and Expertise | Buiten is a law and economics professor at the University of Mannheim. She is the author or coauthor of nine publications, and contributed to others, about law and technology and digitalization, competition law, and European law. |

| Comparison with Other Sources on the Topic | Other sources call for total transparency in legal matters regarding artificial intelligence. This article questions whether such transparency is useful and/or feasible on the basis of current laws |

| Evaluation of Source's Relevance to Topic | Focuses on legal transparency for artificial intelligence, related to the question of whether artificial intelligence is harmful or helpful to society |

| Evaluation of Strengths and Weaknesses | Well-researched; uses dozens of peer-reviewed sources |

| Conclusions Drawn by Author | Transparency for artificial intelligence will be difficult and expensive to comply with and should be better defined in legal contexts before it is required. |

For some sources, you may be unable to find information for each category. In particular, for sources that are very short or from which you use only one or two bits of information, your annotations will not be long or complex, and your graphic organizer may seem sparse. That is to be expected. What is important at this stage is to identify how you will use your resources as they relate to your argument or thesis.

After you have outlined your sources by using the graphic organizer or a similar method, it is time to start writing the actual annotations. Remember the three tasks in writing an annotation:

- Summary the central idea or scope of the source, particularly as it relates to your research project.

- Evaluation the source for authority, author’s perspective, reliability, validity, and bias.

- Reflect on how the source affects your research and your thinking.

Your annotated bibliography should include at least some of these functions and, depending on the source, may contain all of them. Below is an example of an annotated bibliography entry for the article on artificial intelligence. The entry begins with the correctly formatted citation, followed by two paragraphs summarizing, evaluating, and reflecting. Because you already have completed the graphic organizer, much of the analysis is already done there. Simply take that thinking and shape it into useful paragraphs, like those the writer created here.

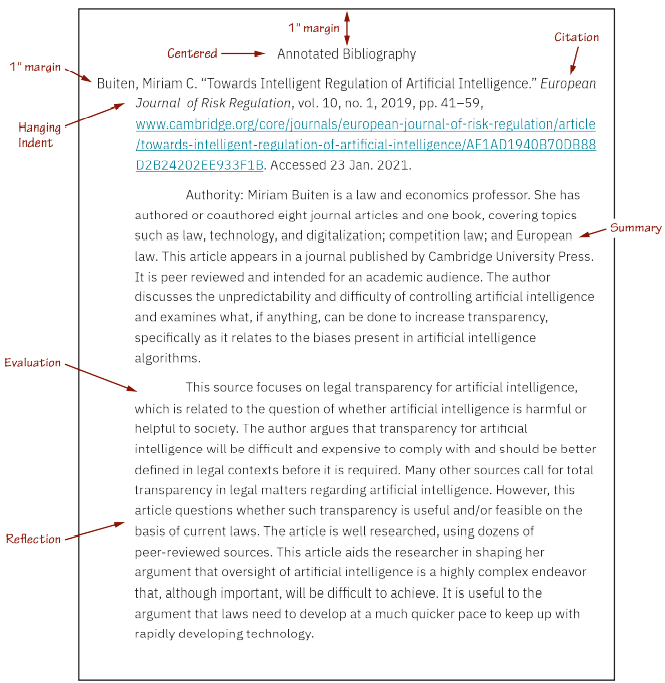

Figure \(14.13\) Sample annotated bibliography entry (CC BY 4.0; Rice University & OpenStax)

You can break down this sample annotation, analyzing each part separately as shown in Figure \(14.13\).

Buiten, Miriam C. “Towards Intelligent Regulation of Artificial Intelligence.” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–59, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regulation/article/towards-intelligent-regulation-of-artificial-intelligence/ AF1AD1940B70DB88D2B24202EE933F1B. Accessed 23 Jan. 2021.

Format. Notice the MLA format, including information listing the author, title, publishing journal, and DOI or link to the article. The reader will be able to find and read the article easily.

Authority: Miriam Buiten is a law and economics professor. She has authored or coauthored eight journal articles and one book, covering topics such as law, technology, and digitalization; competition law; and European law. This article appears in a journal published by Cambridge University Press. It is peer reviewed and intended for an academic audience. The author discusses the unpredictability and difficulty of controlling artificial intelligence and examines what, if anything, can be done to increase transparency, specifically as it relates to the biases present in artificial intelligence algorithms.

Authority. The author is named and introduced with background information establishing her authority in the field. The publishing organization is also named, establishing credibility as a peer-reviewed journal.

Summary. The contents of the text are summarized briefly, allowing readers to quickly understand the topic and scope of the article and to begin to piece together its relevance to the overall research project.

This source focuses on legal transparency for artificial intelligence, which is related to the question of whether artificial intelligence is harmful or helpful to society. The author argues that transparency for artificial intelligence will be difficult and expensive to comply with and should be better defined in legal contexts before it is required. Many other sources call for total transparency in legal matters regarding artificial intelligence. However, this article questions whether such transparency is useful and/or feasible based on current laws. The article is well researched, using dozens of peer-reviewed sources.

Evaluation. This paragraph includes an evaluative statement that shows the article’s validity.

This article aids the researcher in shaping her argument that oversight of artificial intelligence is a highly complex endeavor that, although important, will be difficult to achieve. It is useful to the argument that laws need to develop at a much quicker pace to keep up with rapidly developing technology.

Reflection. This part of the paragraph reveals how the source fits into the research puzzle, noting that it indirectly supports the claim that developing oversight for artificial intelligence is not a simple task and would require the law to evolve quickly.

Style. The annotation is written in third person, referring to “the researcher” and “her,” as opposed to using first-person pronouns such as me and I

Formatting

The format of an annotated bibliography can vary depending on the discipline and purpose. Therefore, be clear at the outset which style you need to use. In academic writing, that information often will come from your instructor. Generally, annotated bibliographies will be written in MLA Documentation and Format, APA Documentation and Format, or Chicago style.

This text uses MLA style. MLA source citations follow several principles in place of specific rules. The style has been adapted in recent years to respond to the evolving nature of text in an increasingly digital world. Thus, the MLA Handbook is organized by the process of citation, rather than listing rules for every type of source. However, certain overall guidelines apply. When you cite a source, first identify core elements that are present. Remember from earlier in this chapter that these are author(s), title of source, title of container, version, number, publisher, publication date, and location.

Buiten, Miriam C. “Towards Intelligent Regulation of Artificial Intelligence.” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–59, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regulation/article/towards-intelligent-regulation-of-artificial-intelligence/ AF1AD1940B70DB88D2B24202EE933F1B. Accessed 23 Jan. 2021.

Author. The entry with gold highlighting begins with the author’s last name, followed by a comma and the remainder of the name. The author’s name is followed by a period.

Title of Source. The title of the source follows the author’s name in purple highlighting. The title is either italicized or placed within quotation marks, depending on the type of source, and followed by a period. Book titles are italicized, while print or online articles are placed in quotation marks, as shown.

Title of Container. The container, highlighted in teal, is the larger work to which a source belongs. An article may belong to a website or journal, a song to an album, or a video to a video-sharing site. This container comes next in the citation. It is generally italicized and followed by a comma. However, some sources do not have containers; for example, a book (versus a chapter in a book) or an entire website (versus a single page on a website) is self-contained and thus has no container to cite.

Version. Next, the version is listed, if there is one. For example, a textbook edition or version of a text would appear here, followed by a comma. This citation example doesn’t have a version, so that information is skipped.

Number. Some sources, especially academic journals, are part of a numbered sequence as shown in green highlighting. Journals usually have both volume and issue numbers; include both in your citation, separated by commas.

Publisher. The next element in the citation is the publisher, followed by a comma. The publisher does not have to be listed for some sources, including periodicals, works published by the author or editor, websites with the same name as the publisher, or websites that host works but do not actually publish them. Because this sample source is a periodical, no publisher is listed in the citation.

Publication Date. List the most recent date of publication available for the version of the source you used. The date is followed by a comma as shown in red highlighting.

Location. Location, shown in dark and light gray highlighting, refers to where in the source you found the information, including page numbers and URLs. Be as specific as possible, as this information allows readers to return to your source to read it for themselves. When listing a URL, remove the beginning tag of http:// or https://.

Optional elements

You may want to add optional elements to help readers identify the source more easily. These can include the following:

- City of publication, generally only for books that were published before 1900 or whose publishers either have offices in more than one country or are unknown in North America (MLA 8)

- Access date, which is present in the sample annotation

- DOI (digital object identifier), which may be used in place of a URL if available

- Original publication date, if it differs from the publication date used for the citation

Alphabetizing and Indenting

Other rules also apply to MLA citations in a research project. Most of these are formatting and style rules that add to a polished final product. Remember to list sources in alphabetical order according to the author’s last name. If the source has more than one author, list it according to the last name of the first author mentioned. If the source has no author named, insert it into your alphabetical list according to the first word in the title. For example, if Miriam C. Buiten’s name were not mentioned, you would enter the item under T, the first letter of the first word in the title, Towards. In your bibliography, double-space the citation, and do not leave a space between entries.

In an annotated bibliography, indent the entire annotation in the same manner as the source citation after the first line. In most word processing programs, you can create this formatting by highlighting the citation and annotation paragraphs and then creating a hanging indent. In Microsoft Word, open the Paragraph Settings icon on the Home tab. Under the tab that reads Indents and Spacing, find the section labeled Indentation. On the right side of that section is the label Special. Click the drop-down menu, and choose Hanging. Different word processing programs may require you to create hanging indentations in another way. Consult an MLA guide often to ensure that your citations are correct.

Annotations

Annotations are the most important part of an annotated bibliography. Although there is no set format for writing annotations, remember to write them in paragraph form and to summarize, evaluate, and/or reflect. Annotation lengths will vary depending on the length of the source, how it is used in your project, and how much analysis you do within the annotation. However, a general length of one to two paragraphs consisting of 100 to 200 words is roughly the standard.

Descriptive/Informative and Analytical/Critical Annotations

There are two major types of annotated bibliographies. The first is descriptive annotations, or informative, summarizing the material and explaining why the source is useful for your topic. This type of annotated bibliography also points out special features of the text, including any data, graphics, or other characteristics. Although you discuss the author’s main arguments and conclusions, you do not analyze or evaluate them. Descriptive annotations are useful for helping readers understand an author’s main ideas but less helpful for showing how the source has influenced the research project as a whole.

The other type of annotated bibliography is analytical bibliography, or critical. This type includes all the features of a descriptive annotated bibliography, including a summary of the material. In addition, it includes your analysis of the information in each source and explanation of how the source has influenced the development of your research. With analytical or critical annotations, you examine the strengths, weaknesses, and biases present in the author’s information and explain how the author’s work and conclusions apply to your research.

In projects for this course, especially those using arguments, you will almost always create analytical or critical annotated bibliographies, though the detail in which you analyze may vary from source to source. The detail in these bibliographies will contribute to your knowledge base and provide information for others.

Further Reading

To learn more about creating an annotated bibliography, consider the following sources:

“Annotated Bibliographies.” OWL: The Purdue Online Writing Lab, Purdue U, owl.purdue.edu/owl/ general_writing/common_writing_assignments/annotated_bibliographies/index.html.

Beatty, Luke, and Cynthia A. Cochran. Writing the Annotated Bibliography: A Guide for Students and Researchers. Routledge, 2020.

“How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography: The Annotated Bibliography.” Cornell University Library, Cornell U, 5 May 2021, guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography.

Works Cited

Krause, Steven D. The Process of Research Writing. 2007, www.stevendkrause.com/tprw/.

“MLA Citation Guide (8th Edition): Annotated Bibliography.” LibGuides at Columbia College (BC), LibGuides, 16 June 2021, columbiacollege-ca.libguides.com/mla/annot_bib.

“MLA Formatting and Style Guide.” OWL: The Purdue Online Writing Lab, Purdue U, 2021, owl.purdue.edu/owl/ research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_general_format.html.